An hour past midnight on 8 February 1969, a fireball lit the skies above the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua.

‘The light was so brilliant that we could see an ant walking on the floor,’ Chihuahua newspaper editor Guillermo Asunsolo told the USA’s Washington Post. ‘It was so bright we had to shield our eyes.’

The burning rock hurtled through the atmosphere before exploding over the village of Pueblito de Allende, scattering debris over a 250km2 (96mi2) region. It was a sight to inspire apocalyptic fears of world destruction. Yet, far from being an omen of our death, this burning spectacle was a memento from our birth.

Rocks that enter the Earth’s atmosphere from space are known as meteors. Hitting the Earth’s atmosphere is a dangerous pastime for a rock, since the air provides a much higher resistance to its motion than the vacuum of space. As the meteor slams into the atmosphere, the air is rapidly compressed, which causes the temperature to soar. This heated air around the incoming meteor lights up, turning small sand grains into shooting stars, while the rare large boulders become fireballs. Such extreme cooking produces a high chance of complete incineration, and most meteors never make it to the Earth’s surface. The ones that do survive this perilous journey have their bravado recognised by being reclassified as meteorites.

The spectacular entry of the Allende meteorite (named after the village over which it exploded) earned it instant fame. Scientists descended on the debris field, assisted in their search for meteorite pieces by local residents and schoolchildren. Among the researchers was a field team from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, which gathered approximately 150kg (330lb) of meteorite material and distributed it to 37 laboratories in 13 different countries within a few weeks of the fall. In total, more than 2 tonnes of material was collected, ranging from 1g fragments to an enormous chunk weighing 110kg (240lb). This massive quantity suggested that the meteor was the size of a car before its explosion. The successive collection and distribution of the rock would help the Allende meteorite earn the title of the ‘best-studied meteorite in history’. However, its size was not the only anomaly that made it important.

In early 1969, research laboratories throughout America were on tenterhooks. They were waiting for lunar rocks from Apollo 11’s historical Moon landing, when another example of a rock from space slammed into their neighbour’s backyard. With the laboratory equipment already primed for extraterrestrial material analysis, pieces of the Allende meteorite recovered from the fall site were examined to reveal that this was no common space rock. Rather, the meteorite’s grey-and-white dotted composition was that of a carbonaceous chondrite: a class of meteorite that accounts for less than 5 per cent of all meteorite falls. It is a class that consists of the very first objects to form in the Solar System, and the Allende meteorite remains the largest example ever to have been found on Earth.

Its early origins make the discovery of a carbonaceous chondrite akin to holding a baby picture of our most distant ancestor. The rock was formed at the very start of our planet’s story, but unlike the Earth it failed to gain sufficient mass to grow into a world of its own. From this physical snapshot of our own beginning, we can precisely date the birth of our planetary neighbourhood precisely.

Laboratory analysis of meteorites reveals that they contain elements that are radioactive, with atoms that can spontaneously change into those of a different element. Due to the random nature of this radioactive decay, it is not possible to say exactly when a particular atom will change. However, for a large number of atoms, scientists can measure with some certainty the time it takes for half of them to decay. This time period is known as the half-life of the element. What this means is that if we know what fraction of the radioactive element has decayed, we have a clock with which to calculate how much time has passed.

One such radioactive element commonly found in meteorites is rubidium-87 (written as 87Rb). The ‘87’ refers to the mass of the rubidium atom nucleus; the central region containing positively charged particles named ‘protons’ and particles called ‘neutrons’, which have the same mass as a proton, but with no electric charge. When an atom of 87Rb decays, one of its neutrons becomes a proton in a process known as beta decay. The result is an atom of strontium-87 (87Sr), which has a nucleus with the same mass as 87Rb, but with one extra proton and one less neutron.

The time taken for half the atoms of 87Rb to decay into 87Sr is 48.8 billion years. This is a good duration for measuring planet-formation timescales. If the half-life was very short (say a few years), then the 87Rb atoms would be long gone before the rock being examined had made it to Earth. On the other hand, if the half-life was very much longer, there might not have been enough 87Sr atoms to measure. Roughly speaking, the time period to be measured needs to be between a tenth of a half-life to 10 times the half-life for the radioactive dating to be accurate.

By measuring the current quantity of 87Rb atoms in the meteorite and the number of 87Sr atoms that the rubidium decay must have produced, scientists can calculate what fraction of atoms must have decayed since the meteorite’s birth. Combined with the 87Rb’s known half-life, this gives the time that has passed since the rock’s first formation.

For a carbonaceous chondrite such as the Allende meteorite, this age marks the very starting point of our planet’s history: a number that comes out as 4,560,000,000 years.

The planet-forming disc

While the Allende meteorite tells us the date of our planet’s birth, exactly what existed at that time is a bigger mystery. Rather than being a clear ancestral family photograph, a carbonaceous chondrite is more like a close-up selfie of a distant cousin, with a date scrawled in the lower corner. Without a better image of the conditions that started our planet’s formation, it is impossible to estimate the likelihood of us ever finding a second similar world.

Although the lack of a better family photographer is disappointing, we do know one fact about our birth epoch: 4.56 billion years ago, our own Sun had just been born. As it happens, this single connection with recent star formation is the only information required to reveal what is needed to build a planet.

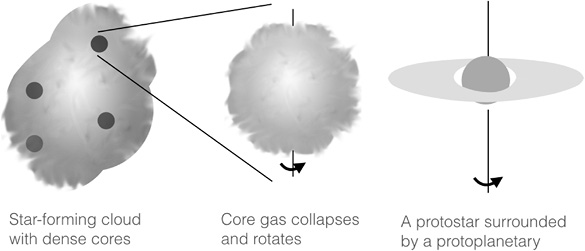

Stepping back another few million years before the primitive meteorite was formed, we end up in one of the coldest places in the Galaxy. This was the Sun’s own nursery: a cloud of gas so cold that its temperature measured a staggeringly low -263°C (-440 °F). Such cloud nurseries are the birth places for all the Galaxy’s stars. Made predominately of hydrogen, these cradles have masses of around 1,000–1,000,000 times that of the Sun. Their creation within the constantly moving Galaxy ensures that their gas is not distributed smoothly throughout the cloud, but shuffles around like a lumpy mattress, gathering in dense pockets of gas known as cores. The high mass concentrated into a small space causes gravity to force the core to contract, increasing its density still more and speeding the collapse. As the gas falls in on itself, it heats and an embryonic star – a protostar – is born.

While gravity may be congratulating itself on compressing material into a star, it is not the only force at work. Knocked about by the Galaxy’s own rotation and interactions with neighbouring clouds, gas within the nursery cloud rotates. Just as riding a children’s roundabout causes you to be thrown outwards, so this spin supports the gas against gravity’s pull. The extra force holds the fastest rotating gas in the core away from the collapsing protostar. The result is like spinning dough into a pizza, and the star becomes surrounded by a rotating disc of gas.

Figure 5 The formation of the planet-forming protoplanetary disc. Stars are born in dense cores in cold clouds of gas. These cores rotate as they collapse under gravity, producing a young protostar surrounded by a disc of gas and dust.

As the gas settles and begins to cool, dust particles condense within the disc, like ice crystals solidifying out of water vapour. These tiny grains join a splattering of dust already in the gas cloud to become the first solids around our Sun. These are the earliest beginnings of planet formation. From these minuscule building blocks, steadily larger objects can be assembled in the rotating gas and dust factory, which is now known as the protoplanetary disc.

This method seems so simple that it appears perhaps a little suspicious. After all, if it were true, then every star would be born with its own planet-making disc. Could planet formation truly be so ubiquitous in the Universe?

One simple test for this is to ask whether protoplanetary discs can be seen surrounding young stars today. The problem with this is that the disc does not shine. Unlike the central star, which is busily warming up to become a ball of fiery glory, the surrounding dusty disc cannot produce its own light. However, the dust will absorb the energy coming from the star. In the same way that a car’s bonnet excels at absorbing the Sun’s rays to get scorchingly hot on a summer’s day, energy from the star’s light will heat the disc dust. The warm dust then releases its heat as low-energy infrared radiation.

The human eye is not sensitive to infrared, but cameras that can detect it are easy to find. Unfortunately, the perfect piece of equipment to image the heat from a night-time robber cannot be turned on the skies to spot a protoplanetary disc. This is because while the disc is heated by its central star, its temperature can still drop to far below anything found on Earth. In order for the camera’s own heat to not interfere with the detection, the equipment must be cooled to temperatures colder than even a stellar nursery. Additionally, the Earth’s own atmosphere is better at absorbing infrared radiation than the aforementioned robber was at running off with your new TV set. Therefore, the best place to put such an instrument is in space.

While substantially easier to keep cold, space telescopes hunting in the infrared still require cooling. This is typically done with liquid helium, which slowly evaporates by absorbing away the surrounding heat to keep the telescope at -270°C (-454°F). Once the helium has evaporated entirely, the telescope warms slightly to a relatively balmy -244°C (-407°F).

Two such telescopes with missions to hunt for discs around young stars were the Infrared Space Observatory and the Spitzer Space Telescope. The first of these was launched in 1995 by the European Space Agency. It continued operating until 1998, at which point the helium coolant ran out. The Spitzer Space Telescope is one of NASA’s four Great Observatories, a prestigious group that also includes the Hubble Space Telescope. It was launched in 2003, and its coolant finished in May 2009, but it continues to operate at a reduced capacity with the warmer temperature. The results from these instruments have been unequivocal: stars younger than a million years old are all surrounded by dusty discs. If the planets form from such a pile of parts, then every new star does indeed have the ability to build new worlds.

Yet these investigations also uncovered another result. While the youngest stars have discs, only 1 per cent of stars beyond the age of 10 million years retain these planet-making kits. This leads to a single conclusion: there is a clock ticking for planet formation.

There are several destructive methods for taking out a protoplanetary disc. The most exciting prospect is that the entire disc will be turned into planets, producing a miasma of new worlds. Unfortunately, observations of both our own Solar System and known exoplanet systems show that their total eventual planetary mass is only 1 per cent of the initial disc mass, leaving a question mark about the remaining 99 per cent.

Another possibility is that nearby stars pull on the disc with their own gravity, stripping it away from its host sun. This process may occur occasionally, but it isn’t thought to be a common enough event to be responsible for the complete obliteration of all protoplanetary discs; stars are typically just too far apart. The destruction must therefore be an inside job: that is, the forming star and disc system destroys itself.

Some of the blame for the destruction is due to friction within the disc. We can picture this by imagining the disc as a consecutive series of running tracks around the star. Gas in the inner track pulls ahead of gas in the adjacent outer track. Friction between the tracks slows the speedy inner gas, reducing its rotational support against the protostar’s gravitational pull. The outer gas increases in speed from the forward tug of the inner gas track, but is slowed in turn by its own neighbouring outer track. As the rotational support diminishes in the disc, the gas and suspended dust fall towards the star.

This inward flow is called accretion and it is certainly responsible for removing a portion of the disc. It does not represent the whole answer, though, as the process is rather slow. To remove the outer parts of the disc via accretion would take several thousand million years, yet observations tell us that we only have about 10 million years to get the job done. More damningly, very few discs are seen in the process of partial destruction, suggesting that the actual demolition time is 10 times shorter still, and must take place almost simultaneously across the whole disc. This last part is a particular problem since accretion turns out to be fastest closest to the star, so eats away at the disc from inside out. What is needed is a second, faster destructive force, and this is provided by the star itself.

Like a teenager going through a painful adolescence, the progression from the young protostar to a fully fledged sun is an angry process. In the case of an intermediate-mass star like the Sun, this rebellious stage is known as the T-Tauri phase, named after the first star to be observed at this awkward moment, in the constellation of Taurus, the Bull. In a similar manner to throwing insults at protective parents, T-Tauri stars throw out damaging radiation in the form of high-energy ultraviolet and X-rays, along with winds packed with a blowtorch of high-energy particles. These hit the upper gaseous layers of the disc and heat it. Close to the star, the result of this energy bombardment is just a very hot disc. Further out, however, the pull from the star’s gravity is weaker, and this energy can be enough to allow the disc gas and smallest dust grains to escape as a wind. This is known as photoevaporation (literally ‘evaporation from photons’, the particles of radiation), and is the process thought to be responsible for the destruction of the main part of the disc. Close to the star where the gravity is sufficient to hold against photoevaporation, accretion then finishes the job.

Once the gas disc has been removed, the only freewheeling pieces will consist of planets and other solid objects big enough to have avoided being carried off with the gas. Most gas still in the system is now already part of a planet, where it can be held in place by the planet’s gravity. Since our Solar System contains four planets with a huge part of their volume in their gaseous atmospheres, we know that the planetary neighbourhood must be nearly finished by the time the disc is destroyed. This gives us approximately 10 million years to go from a pile of dust particles 10 times smaller than a grain of sand, to an entire world that looks as though it might one day host life.

At this point, it would not be unreasonable to suggest that this seems to be a near-impossible task. So much so, that one might propose that the discs visible around young stars are not planet-forming entities at all, but merely the dusty placentas of new-born stars. One way to test this hypothesis is to ask how much material must have been in the Sun’s protoplanetary disc to produce the Solar System. If this is vastly different from the mass of discs observed around young stars, then this progression from dust to planets must surely be bunkum.

Had we mimicked this assembly process by building a model of the Solar System out of LEGO bricks, the job of finding the quantity of starting materials would be easy. By breaking up the construction and counting the number of plastic bricks that had been used to form the planets, we could accurately state the number needed to complete such a project. However, when doing this for the protoplanetary disc, we have the problem that a compulsive kleptomaniac – the Sun – always steals a large fraction of the bricks during the assembly process.

If all the planets in the Solar System were broken down and smeared out to form a disc, the resulting system would be rich in iron and silicate compounds containing silicon, magnesium, carbon and oxygen, with ices being abundant further from the Sun. These were the heavier elements that condensed most easily out of the gas and into solids, forming dust and then (our mechanism proposes) larger rocks and planets. While lighter elements such as hydrogen could bond on to the dust grains to form solid compounds such as ice or be captured in planetary atmospheres, most were evaporated from the disc by the young Sun’s radiation.

Reporting this deficiency of light materials to an insurance company would probably result in being told that our story was unbelievable unless we could prove the quantity we originally possessed. This would seem a tall order, except that if the disc formed from the same stellar-nursery gas as the Sun, we have a comparison point for the material it must have initially contained: the Sun itself.

If the toy Solar System model were made from a box of coloured bricks and the brick stealer had a strong preference for red, assessing the number of bricks used in the construction would be much easier. By knowing that the bricks used in the assembly came in an equal mix of red, green and blue colours, we could estimate the number of missing red bricks from the total numbers of the other two colours. For example, if we disassembled our model to find it contained 100 green bricks, 100 blue bricks and five red ones, then it would be reasonable to assume that 95 red bricks had been taken, and our original number totalled 300 bricks.

It is this same technique that can be used to find the quantity of missing elements in the protoplanetary disc. Forming from the same gas core, the disc and Sun must originally have had the same ratio of elements. Like the red bricks, the volatile elements in the disc have been removed, but their number compared to the heavier elements must be the same as in the Sun. To estimate the original disc mass we can therefore add lighter elements to the disc of crumbled planet parts until the ratios between each element equal the solar amount. This does assume that the Solar System was perfectly efficient in gathering into planets the heavier elements we do see into planets; in reality, some of this mass will have been lost during the adolescent Sun’s T-Tauri temper tantrums. Nevertheless, it gives us an absolute minimum for the mass needed to form the Solar System. That value is known as the Minimum Mass Solar Nebula (MMSN), and it turns out to be around 3 per cent of the Sun’s mass. This also happens to be similar to the estimated mass of the observed discs around young stars.

Particularly spectacular evidence that the protoplanetary disc can yield a solar system full of planets came from another rock. On 9 May 2003, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency launched an unmanned spacecraft to land on an asteroid named Itokawa.

Asteroids are rocks typically a few kilometres to a few hundred kilometres in size that mainly sit between Mars and Jupiter. Collisions between asteroids can send fragments scattering towards the Earth, some of which end up smacking our planet as meteorites. One such collision early in Itokawa’s history had pushed the asteroid on to a new orbit closer to the Earth, making it an easy-to-reach target for a spacecraft.

Japan’s spacecraft was called Hayabusa, translating to peregrine falcon in English, and it both photographed the 550m (800ft) long Itokawa and brought home samples from its surface in June 2010. Images from the mission showed a peanut-shaped object that consisted of a rubble pile of many different-sized pieces. Rocky boulders and dusty granules were held together loosely by Itokawa’s gravity, which was not strong enough to pull the asteroid into a dense round ball. Missions to different asteroids supported this view of a collection of irregular lumpy rocks. Such a morphology must have developed from the collision and sticking of the smaller visible pieces, evidence of this factory assembly mechanism in action. The result is the planets and the remaining asteroid rubble; the dust on the factory floor.

This dusty gas disc is therefore truly the planet-building factory floor. From here we begin an assembly that will take us from grains of dust to eight new worlds between 10,000 billion and 100,000 billion times greater in size. It is the greatest construction process in the Universe, and it has taken place around each and every star you see in the night sky.