12

1866–69

Good Deeds Rewarded

Henry’s business fortunes rose and fell, yo-yoing almost as wildly as shipping and timber prices. The reason was timing. Investment in labour represented the main cost of getting the timber and raw goods from Canada’s interior to the shipping ports, principally Quebec. Merchants advanced the money to cover the costs. A year or more could pass before they got it back, and who knows what would happen during that time. It was a credit structure unintentionally designed to exaggerate fluctuations in prices and profits. “Little wonder that the psychological traits of mania and despair were so identified with the timber trade,” reflected a twentieth-century historian. “A breath had made it, and a breath might take it away.”[1]

Widespread financial panic occurred on May 11, 1866, when the greatest private banks in England unexpectedly failed. “Black Friday was the darkest day London has seen since the South Sea Bubble burst of 1720,” observed Henry.[2] Later that year the pace of business became more hectic with the completion, finally, of a fully functional telegraph cable from Newfoundland to Ireland. Newfoundland was linked to New York.[3] Transatlantic trade was revolutionized. Instead of a message crossing the ocean by ship in ten days, it now took minutes.

After the banking crisis, mercifully, three years of prosperity ensued. Henry had become the sole owner of Lotus, one of his favourite ships (see chapter 6). He put her in Dinning’s dock, where he spent $9,000 on repairs, among them the replacement of deck, topsides, and top timbers. Much as he loved Lotus, though, the ship had given him trouble — human, not maritime. The trouble arose when two of Henry’s strongest character traits had come into conflict — ship management versus family obligation.

“As eldest son,” he said, “I deemed it my duty to do all I could to help my brothers.” In 1863 he’d put twenty-five-year-old Samuel Holmes Fry, formerly first mate, in command of Lotus. The trouble was that Sam, in Henry’s words, “had a queer temper, and in 1865, in a very surly manner, declined to sail the Lotus any longer, as he said he wanted a better ship. I was vexed, as prices were high, but … I went up to London and bought for 4,300 pounds a very fine New Brunswick–built ship specially for him, Constance, built by Wright of St. John for the Australian passenger trade. She was a sharp model (178 feet long with a 36-foot beam) and very fast (sailing at a speed of thirteen knots when deeply laden) and in every respect a superior ship.”[4]

No good deed goes unpunished. Notwithstanding Henry’s generosity, in 1867 his incorrigibly resentful brother grossly insulted him again, in his home. This time, an angry Henry was unforgiving: “I requested Sam to resign. He had saved some £600 while in my employ, and on this he afterwards lived in idleness until it was spent.”

As for Lotus, she continued to sail the high seas, although not lucratively. “I held on to her too long,” wrote Henry later in life. Worst was the tragedy it brought. “In the winter of 1874,” he recorded, “Lotus shipped a sea over the poop which carried overboard and drowned Captain John Harris, a most worthy man, plus the man at the wheel. Captain Harris’ widow died soon after of grief. It was the worst accident that ever befell a ship of mine,” Henry wrote.

Canada’s Newport

The summer of 1866 had been hot, as often happens in Quebec. In Lower Town, where Henry worked, the high south-facing cliff above partly blocks northern breezes that might cool homes and offices. The previous year Henry had the idea that his growing family would enjoy relief if he were to own a cottage on the fashionable south shore of the St. Lawrence where the river widens into the beginning of the Gulf of the St. Lawrence, and where refreshing air from Hudson Bay and Ungava streams for miles shoreward across the cold water.

Actually, it would be more accurate to say that Henry’s summer home idea may have been implanted in his head by the entrepreneurial Quebec lumber merchant and banker Andrew Thomson, who had the idea for a second-home real estate deal — four side-by-side cottages on a cliff overlooking the broad St. Lawrence River. The location was Cacouna, a resort village about 120 miles downriver from Quebec. One cottage would be for Thomson; one for his father-in-law, the Reverend John Cook, minister of St. Andrew’s Church in Quebec, who in 1875 would become moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Canada; and one for Cook’s brother-in-law, the wealthy Reverend Charles Hamilton, rector of St. Peter’s Anglican church in Quebec City, who later would become the first bishop of Ottawa.

Henry, a sucker for ecclesiastics, was easily talked into purchasing the fourth lot for $175. Less certain is whether the ranking clerics appreciated the close proximity of a fervent Baptist. But it was a delight for Henry. Laymen like Henry with an appetite for knowledge gravitated in their friendships toward clerics who were typically nineteenth-century society’s better educated people … and the higher up the ecclesiastical scale, the better.

The four identical 2,800-square-foot Cliff Cottages, designed by Quebec architect Edward Stavely, with walls built of squared timbers and floors of thick finished deals, were up and finished by November 1866.[5] From the lawn in front of his new second home, with a telescope, Henry could glimpse his own square-riggers plying the river. Tennis and croquet were also played on the lawn, a former potato field, with the Gulf and the Laurentian Mountains on the opposite shore as a backdrop. The ruby-red sunsets have always been spectacular. In the month of May, tens of thousands of snow geese congregated in the vast marshland east of Cacouna before flying north to James Bay. (They still do.) In August, untilled fields and carriage roads were lined with blazing red fireweed, purple loosestrife, and white Queen Anne’s lace. Henry fell in love with the place.

Bliss on the south shore: Cliff Cottages at Cacouna on the lower St. Lawrence River, where Henry and two of Canada’s leading clergymen made their summer homes in 1867. The Fry cottage, at the far end, as it is now. The cottages face across the river toward the mouth of the Saguenay River, with a view of spectacular sunsets.

Notman Collection, McCord Museum, MP-1984.107.38. (top), photo by the author (middle and bottom)

Cacouna was known in the late nineteenth century as “the Newport of Canada,” suggesting that it ranked with the Rhode Island summer home of America’s upper class. Henry’s brother-in-law Sam Dawson, Mary’s brother, described it as “famous for the dancing and flirting, and a dangerous place for an unengaged bachelor, or even for an engaged one, if his fiancée be not there to monopolise him.”[6]

Cacouna was, as well, a summer retreat for the elite — among them a founder of the mighty Allan Steamship Company, and the banking and brewing Molson family. In nearby St. Patrick, Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, enjoyed the ownership of a summer home.

Sirs John and Narcisse

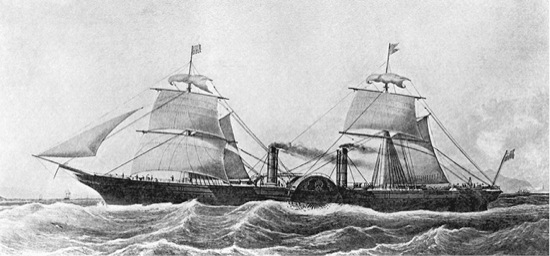

During the winter of 1867, Henry was in Bristol, occupied with business; at the same time, in London, the widowed John A. Macdonald was occupied in marrying himself to his second wife, Agnes, while shepherding the British North America Act through Parliament and the House of Lords. With that historic accomplishment, Macdonald and his new bride in April boarded the sail and paddlewheel steamship Persia in Liverpool to return to the new Dominion of Canada. As it happened, Henry was one of the 250 passengers on that voyage to New York.[7]

Steamship Persia: John A. Macdonald and his new bride, Agnes, travelled home on the passenger ship Persia in April 1867 after British government go-ahead for Canada’s Confederation. On board as well was Henry Fry. When built in 1856, Persia was the world’s largest steamship.

Image from Heritage Web.

Cunard’s Persia was “a great favorite with passengers,” Henry wrote, “making the Atlantic crossing typically in less than ten days, moving through the water above thirteen knots average.”[8] When built in 1856, the 376-foot-long, 3,300-ton Persia was the world’s largest steamship. The Macdonalds and Henry could stroll on a roofed promenade from stem to stern and take their meals in the main dining salon — sixty feet long and twenty feet wide.

Back in Canada on July 1, 1867, Henry joined the throngs celebrating the first Dominion Day. Bands paraded and fireworks lit the sky. Quebec City was now the capital of the province of Quebec. To celebrate the occasion, the first lieutenant governor, Sir Narcisse-Fortunat Belleau — avocat, politician, and former Quebec mayor — sailed down from Montreal. Henry recalled that he was “among a great crowd on the wharf,” waiting to greet the new lieutenant governor. Sir Narcisse selected Henry, soon to head the Quebec Board of Trade, to accompany him to the hotel reception.

“It happened that Sir Narcisse looked upon me as a representative English merchant,” Henry recalled. “He bestowed on me repeated acts of kindness, which I can never forget. I often dined with him at the Stadacona Club, and on one occasion at Spencer Wood [the lieutenant governor’s residence] where I met Prince Arthur [Queen Victoria’s son].” Henry additionally admired Belleau for always “looking on the bright side of human nature.”[9]

On the occasion of Sir Narcisse’s death in 1894, Henry wrote a tribute to the farm-born lieutenant governor in the snobbish, condescending manner that would be infuriating to francophones for another century. “He [Belleau] will long be remembered as a kind-hearted, genial specimen of the old French Canadian regime, which, while not displaying the energy or force of the Anglo-Canadian, had many fine qualities which will be looked for in vain amongst the great majority of the modern ‘go-ahead’ trading class.”

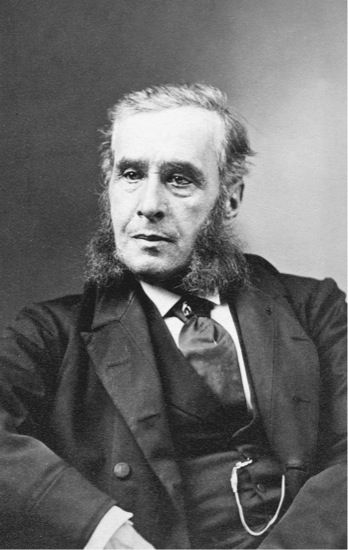

Sir Narcisse-Fortunat Belleau: The first lieutenant-governor of the Province of Quebec, 1867, regarded Henry Fry as a representative of the British merchant class. Fry, in turn, regarded Belleau as “a kind-hearted, genial specimen of the old French-Canadian regime.”

Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec.

A Good Deed Rewarded

In November of 1866, Mary gave birth to the couple’s fourth child, Arthur Dawson. With the infant, six-year-old Mame, four-year-old Henry, and two-year-old William Marsh, the family spent the winter of 1867–68 in Quebec. The town was still recovering from the devastating October fire of 1866.

“Times were bad,” Henry wrote later. “There was much distress among the ship carpenters of St. Roch … so much so that a meeting was called to promote soup kitchens. I attended the meeting and denounced the proposition on the ground that it would tend to make the men paupers. ‘What they want,’ I said, ‘is not soup, but work, and there are wealthy men in this room who can provide it without loss.” As president of the Board of Trade, Henry believed that the assembled businessmen — merchants, ship-owners, bankers — should fund the construction of a half-dozen ships, immediately providing the money for wages. For his part, Henry would undertake to sell the ships, charging no commission.

“In this way,” he told the group, “you will run no risk, get all your money back, and provide for the 5,000 souls. I will undertake myself to build one [ship].” The businessmen enthusiastically approved Henry’s initiative. “I supposed them to be sincere, so I went at once to McKay & Warner [shipbuilders] where I signed a contract for a ship of 800 tons costing $38 per ton.”[10]

When he looked back, however, Henry found no one following him. A few people donated token money to help the destitute, but none pursued his example of building ships to create jobs.

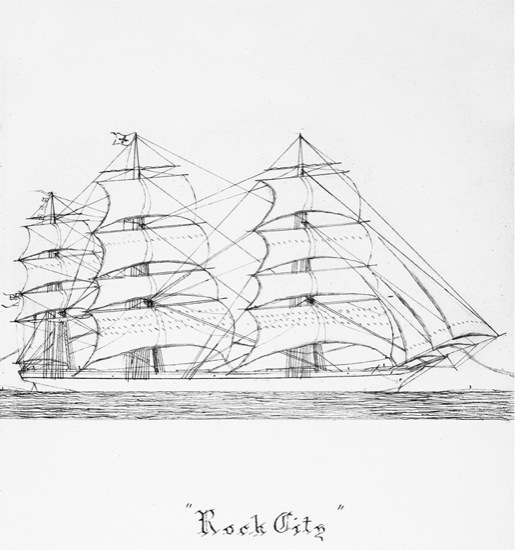

During the winter he watched and superintended as carpenters and yard craftsman built the ship Rock City. In the end, Henry’s charity was rewarded:

Rock City proved the most fortunate and profitable ship I ever owned. She was a good model, a very handy ship, nicely sparred, with double diagonal ceiling, extra fastenings. She was launched in May 1868. I ran her for five years between London and Montreal, and she cleared $32,000. Then she ran another five years in the Buenos Aires and Peruvian trade, clearing $25,000 more, in all about $57,000 in ten years. But new wooden ships depreciate fast, reducing her net profits to somewhere about $32,000.[11]

A wooden ship, it’s true, did not have the service life of an iron ship, and while wooden shipbuilding’s demise was not immediate, its inevitability was. The low cost of iron was causing builders to steer away from wood. And the prospect of the Suez Canal opening in November 1869 would further darken sail’s future.

Rock City: A profitable ship built originally in 1868 by Henry to provide winter work, rather than soup kitchens for unemployed yard workers and their otherwise destitute families.

Pen-and-ink illustration by Henry Fry, 1891.

Quebec, however, proved incapable of switching to the mass building of iron ships. It needn’t have been so, believed Henry and other shipbuilders. There was an alternative. Quebec could forestall the inevitable by switching to the construction of composite ships, having frames, beams, and stringers of iron, and outside planking and ceiling of wood. On March 9, 1868, Henry led a deputation of the Quebec Board of Trade in appealing to the government.[12] He explained that iron freighters cost not much more than wooden ships to build, and that after twenty years they were still in excellent service, whereas the wooden vessels were near the end of their useful life.

“Are they as safe?” asked then prime minister of Quebec, P.J.O. Chauveau.

“They are stronger afloat,” replied Henry, “but break up quickly if they run aground. There are other objections, too, such as bottom fouling and drainage from sugar eating away the heads of rivets.” The solution, he said, was a composite ship: “It combines the strength of an iron ship with the safety of a wooden ship. I believe these will be the ships of the future, and they can be profitably built in Quebec. In order to commence building them, however, it will be necessary to import costly machinery, and instruct the workmen in the new mode of construction. Our shipbuilders are men of small means, and cannot at present afford such an outlay.”[13]

In effect, a government subsidy was needed to kick-start composite ship construction. The subsidy never came. Two years later, it’s true, William Baldwin did lay the keels of two composite ships, with iron keelson, frames, knees, and deck beams.[14] But a few weeks before the ships were ready to be launched, another devastating fire struck St. Roch. The area around Baldwin’s yard, and the two ships in it, were destroyed. They were the only composites ever built at Quebec. With the notable exception of the Davie yard on the Levis side of the river, Quebec’s shipbuilders stuck with wooden construction.

“The days of wooden ships were fast coming to an end,” Henry wrote. “I did not have the capital to build iron ships alone.” Perhaps not, but in 1867 he failed to join other Quebec investors in a new venture, the Quebec & Gulf Ports Steamship Company, precursor of the Canada Steamship Lines.[15]

He did make one iron-ship investment, however. Early in 1869, when he was in England with his wife, two small boys, and nursemaid, he ran into Alex Ramage, a Liverpool merchant and ship-owner. Ramage had the idea of building fast iron sailing ships to run to Montreal. “If you will finance a quarter of one ship,” he told Henry, “you can have the Canadian agency.” Henry took him up on it, and wound up owning a piece of the 190-foot, 895-ton Oceola. “She was almost like a yacht,” Henry recorded, “very fast, paying pretty well.” The Oceola’s life was short, however. In October 1871, the iron barque Marmion ran into her off the Welsh coast. Oceola sank within five minutes. The captain and most of the crew were saved, but five men who jumped into one of the boats lost their lives. The tragic collision was the fault of Marmion, and Henry recovered most of his investment.

George Fry, eighty-five, beloved father of Henry, died in Bedminster, Bristol, in June of 1868. Henry and family did not reach England until November. In the spring of 1869, after four months, they returned to Canada, accompanied by Mary’s father, Benjamin Dawson, retired Montreal bookstore owner and magazine and newspaper distributor. Their North Atlantic crossing from Liverpool to Quebec was made in a new record fast time of just under nine days on the steamer Austrian. On the final day, the family stood on the port deck and glimpsed the cliffs of Cacouna, where their new cottage stood.

Back in Quebec, they resumed living in the house on des Carrières, behind which a stable housed the family’s horse and carriage. On Saturday night, July 14, Henry and Mary took out the carriage and drove to a party. On their way home, a bicyclist dressed in dazzling white appeared out of the darkness on St. Foy Road, pedalling furiously in swooping curves. Henry shouted at him, warning that he could frighten the Frys’ horse. The cyclist paid no attention. Terrified, the horse reared up, overturning the carriage and throwing the occupants to the ground. “Mrs. Fry received some quite serious bruises,” reported the French-language weekly Le Courrier du Canada. “Mr. Fry escaped with a few scratches.” The newspaper went on to warn, “If velocipede riders are not more careful, they will end up with a very bad reputation. If they carry on in such a manner, we see no reason why the authorities should not intervene.”

Back at home, Henry and Mary’s row house on des Carrières was filled with the cries of five children ranging in age from one-year-old Alfred to eight-year-old Mame. The children could play on the terrace. Or they perhaps could walk a hundred yards to the Governor’s Garden and gaze at the now famous monument dedicated to Generals Wolfe and Montcalm.