24

1882–89

Miracle and Mystery

Henry and Dr. Hallock arrived on June 2, 1882, in Quebec, where Mary, Henry’s wife of twenty-four years, was petitioning the court to declare her husband incapable of handling his affairs. Mary had come down from Montreal where she was living. She appeared grim during the reading of her petition for interdiction — a legal restraint imposed on someone judged incapable of managing his estate due to mental incapacity.

To my honorable Judge of the Superior Court the petition of Dame Mary Jane Dawson respectfully showeth that for some time past her husband Henry Fry has been and now is suffering from mental disease and is quite incapable of transacting his affairs. He has been for a long time in an establishment under treatment, but there has been no improvement in his condition. The petitioner asks that the court interrogate Henry.[1]

The man who now came before the court bore a pitiable resemblance to the vigorous merchant who’d once walked Quebec’s corridors of power. Henry’s hair had turned grey and disordered, his face appeared sallow, his hands raw and red, his eyes dead. He shuffled into the courtroom. On the stand, he responded in a wavering, despondent voice. He was asked where he had been living.

“I have been residing partly in New York and partly in the village of Cromwell,” answered Henry. “At an hotel and private house.”

“Have you not been in bad health? What was the cause?”

“My health has not been as good as usual … more from absence of my home and friends, but I attribute the original trouble to the doctor’s mistake. Being a sensitive man, he gave me narcotics, which I think was a mistake.”

“You consider that you cannot yourself manage your affairs?”

“Though being necessarily absent, I consider myself able to do so. My brother is very competent to do that. He is my partner.”

“Where do you intend to reside in future?”

“I do not know. They give me narcotics every night. It stupefies me.”

So stupefying that the court recorded, “the said Henry Fry goes on speaking in incoherent manner.”[2]

Dr. Hallock was summoned to the stand, where he deposed.

I, Winthrop B. Hallock of Cromwell, Connecticut, have devoted much attention to insanity and to the various forms of mental illness. Henry Fry of Quebec has resided with me under my immediate care and treatment for about one year. I came with him from Cromwell to Quebec this week. The form of mental illness under which Mr. Fry has been suffering would be classed as monomaniacal hypochondria: an inability to talk or think except for a short time about any subject but his own bodily and mental state. When not in the presence of others, he will talk and laugh to himself. He gnaws his fingers, keeping them constantly raw; he wakes from sleep in a half-delirious state, he cries and moans imagining he is going to die. I have no hesitation in saying that he is insane and quite unfit to attend to his affairs.[3]

Hallock’s expert testimony was supported by two Quebec physicians and surgeons — Colin Sewell and James Arthur Jewett. By two o’clock in the afternoon the interdiction of Henry Fry was complete. With the approval of Henry’s son Henry Jr., his brother Edward, his brother-in-law Samuel Dawson, the banker James Stevenson, and his Cacouna neighbor Andrew Thompson, Henry’s wife was appointed curator, or curatrix, as the court noted. She was to take charge of her husband’s “person and to administer his property.”

For the forty-six-year-old mother of seven children it was a heavy, unenviable burden. Worse, with it came the shame of Henry’s official listing as an interdicted person in Quebec. “Notices of said interdiction must be transmitted to the Notaries of this District of Quebec in order that no person be ignorant of the said interdiction.” In short, Henry was publicly declared unable to transact business in the city over whose Board of Trade he’d once ruled, where he’d built great fully rigged sailing ships, kept families from hunger, founded the YMCA, served as school commissioner, fought crimping, saved the lives of sailors imperiled by faultily loaded cargo, and guarded the St. Lawrence River and thousands of ships traversing its dangerous waters. The city he loved had formally rejected him.

To wind down Henry’s affairs, Mary gave wide powers to the Quebec merchant Richard Reid Dobell. By November her oldest son, Henry Fry Jr., joined Edward Fry as a partner, and the two undertook to manage the business of Henry Fry & Co. The partnership lasted about two and a half years. At the end of April 1885, Edward took over for himself the business that had been launched by his oldest brother in Quebec thirty years earlier.

Mary, gathering cash from the sale of bank shares, moved permanently to Montreal. For income she had loans outstanding to no fewer than nine people, who were paying her interest rates between 5.5 percent and 7 percent, secured by their real estate and insurance policies on their houses. She owned properties herself.[4] Shrewd in finance and real estate, Mary saw that there was enough money for her husband’s care. But he was no longer the man whom she was once married to. Lovell’s 1887 Montreal Directory lists her as “Mrs. M. Fry, widow.”[5] In December 1877 she bought a house at 66 McTavish Street, conveniently located across the street from the McGill campus. Convenient because twenty-five-year-old Henry Jr. was studying law at the university on his way to becoming a well-known Montreal notary.

The matriarch: In 1886, Mary Dawson Fry, then fifty, was living in her own house in Montreal across from the McGill University library, separated from her husband, Henry, who was living southeast of Montreal in the region known today as Estrie.

Photo courtesy of Dick Avison.

As for Henry Fry Sr., he likely travelled from Quebec with Dr. Hallock back to Connecticut, where he remained for a while under his care. How long is unknown.[6] At some point Henry moved to the town of Farnham in the Eastern Townships (Cantons de l’Est, or Estrie). Hallock, perhaps sensing that Henry wished to go back to Canada to be nearer to his family, may have referred Henry to Dr. George F. Slack, a Farnham physician. Slack was known to use a pioneering treatment for mental patients.[7]

At the same time, the family appears to have wanted him in Montreal. In October 1888, Mary gave Henry Jr. $10,800 to buy a stone cottage on Fort Street, then in Montreal’s west end. Henry Jr. said he “acquired the property for his father.”[8] Did Henry actually come to live in the cottage? Wherever he lived, it was clear that Mary didn’t wish him to reside with her on McTavish Street. The wounds of his mental illness had not totally healed. The discordant qualities of restlessness, fretting, and irritability are the hallmarks of depressives, with whom even the most patient and tolerant of humans have difficulty co-habiting.[9]

In 1889, however, Henry reappears, suggesting that he’d partially recovered. It was in writing. Henry’s own writing. Something of a miracle had occurred.

A Fresh Beginning

In the summer of 1889 in Quebec, the city where seven years earlier he’d painfully demonstrated his stultifying mental illness, Henry wrote an exquisite tribute — highly literate in the quality of its expression — to his dearest male friend, the Baptist minister David Marsh, who had just died. The next year he completed more than three hundred pages of Essays on trade, tariffs, and U.S.-Canada relations, which a hundred years later would find their way into the stacks of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto. The Essays were “written for, and dedicated to my children,” who now ranged in age from the unmarried and sickly twenty-nine-year-old only daughter Mame to sixteen-year-old Ernest, youngest of his six sons.

For two of his sons, Henry and Arthur, he completed the book Reminiscences of a Retired Shipowner, accompanied by twenty-three flawlessly executed pen-and-ink illustrations which he made of ships that he’d owned. He wrote Notes on England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and Paris, a 183-page travelogue to educate “a young Canadian.” He made pen-and-ink drawings, with captions, of ships from Columbus’s square-rigged Santa Maria to the 1890 steamer Empress of India, including barques, brigs, fore- and aft-rigged schooners, and combined sail and paddlewheel ships.

The sheer volume of Henry’s writing in such a short period suggests activity almost manic in its intensity, a man who slept little. All the while he was researching and writing his final and most researched work, The History of North Atlantic Steam Navigation, which would be published in London in 1896 — a work written, he confessed, “during a period of enforced leisure from ill health.”

“Enforced leisure”? What did it mean to Henry? Leisure enforced by doctors to enable his cure? Leisure time available to write because his interdiction barred him from working again as a merchant? Or self-enforced leisure because he was cured, clear of mind, and quite able to manage his time?

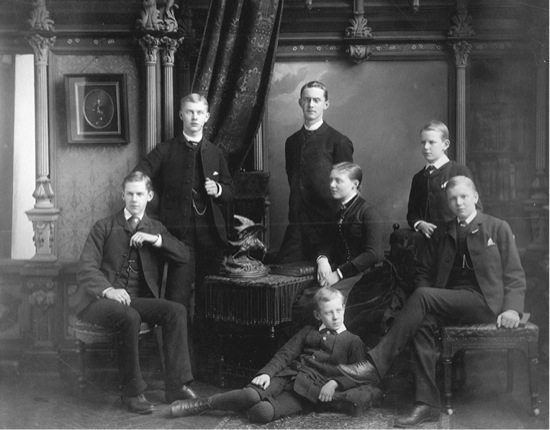

Sons and daughter: Children of Henry and Mary Fry circa 1885, left to right: Arthur, William, Henry, Mamie, Frederick, Alfred. Ernest in foreground.

Photo courtesy of Dick Avison.

Throughout his worst bouts of depression and self-doubt, Henry never totally lost the temporary capacity to think normally and clearly, and to write intelligibly. From moments those episodes extended to mornings, then to whole days of essay and letter writing, drawing ships, and research.

The 1891 Census of Canada clearly records Henry as living in the bustling town of Farnham, with a woolen mill and tannery, on the main rail line between Montreal and Vermont. He was renting a room or rooms in the house of Joseph Massicotte, a tinsmith with a wife and four children under the age of ten. He was living two doors away from his physician, Dr. Slack, who owned several properties in Farnham, possibly including the Massicotte house where Henry was residing. Henry’s granddaughter says that he was under the care of Dr. Slack for a long time, and Slack remained his primary physician until the day Henry died.[10]

The 1891 Census contained a column indicating whether the subject suffered from “Infirmities.” The Henry Fry entry suggests the information was provided when he was absent, by someone in the household who recorded whatever Dr. Slack had once dictated.[11] Henry was listed as a person “unsound of mind,” and the enumerator takes the unusual step of entering what appears to be the word insomnia. That he suffered from insomnia would hardly be surprising, given the immense volume of work Henry was doing at the time of the census — countless handwritten words, scores of illustrations.

The census was outdated by the time it was published. Henry, apparently sound of mind, had transferred his powerful mercantile energies into intense, studious research, and thousands of words and hours of writing. They reveal the thought of a nineteenth-century Victorian in Canada, loving his Quebec home, suspicious of Americans, assumptive of Anglo-Saxon superiority, vocally proud both of Canada and the Empire of which, in his mind, Canada was an indissoluble part.