6

1856–59

Crime, Business, and a Wedding

In the year 1856, Quebec briefly became the capital of the Dominion of Canada by vote of the Legislative Assembly.[1] At the same time, Henry Fry & Company came into existence, occupying an office on the most prominent business street in Quebec’s Lower Town, St. Peter Street (now Rue St. Pierre). The first horse-drawn streetcars began to rumble through Lower Town.

Henry’s financial condition, and that of his company, wasn’t especially robust. He had less than £1,000 of capital … not much when a year could pass between the time you purchased goods and paid for shipping them and when the customer in England finally paid you. But William Yeo, who’d helped Henry after Whitwill put the screws to the young shipbroker, kindly lent him $25,000 to capitalize the business.

“I made such a good year in commissions, lumber contracts, etc., that I cleared $7,000,” recorded Henry.[2] With the money he was able to pay off his debt to Whitwill.

In 1856, a total of forty-two sailing ships were launched from Quebec yards, an annual amount typical for the 1850s.[3] Plenty of skilled manpower was available to build the ships. The local population’s shipbuilding skills, however, weren’t matched by any indigenous seafaring skills. Quebec-born sailors were in short supply. When a ship was launched from Quebec yards, the captain had to recruit the crew elsewhere, perhaps from Boston or New York, or from men running away from other ships. As many as a thousand runaways manned new ships sailing out of Quebec in 1856.[4] The runaways themselves were frequently victims of crimps — thugs who boarded an arriving ship and captured its crew members, or who got them drunk in taverns ashore, seized them, then delivered them to another ship about to sail out of Quebec.

“The shortage of labour in Quebec was so severe that it turned the seaman into a high-priced commodity whose arranged desertion became the staple trade of the Lower Town of Quebec,” writes Judith Fingard in Jack in Port.[5] “There were 200 to 300 crimps in Quebec at mid-century, composed of the lowest characters in the city.… In their resort to chicanery, force, assault and murder, the crimps of Quebec could hold their own with their counterparts in New Orleans, San Francisco or Shanghai.”

The cruelty and corruption angered Henry, and in 1856 he wrote to the Times of London, a letter subsequently reprinted in Quebec newspapers:

The crimping system has now reached such a pitch [that] the force of law is completely set at defiance. Night after night ships in this harbor are boarded by crimps well armed with revolvers, the crews carried off, masters and officers threatened with instant death if they resist or interfere, and the owners’ property plundered wholesale. And for this state of things, the authorities here either cannot or will not find a remedy. I can cite scores of instances to prove the truth of the above. Piracy stalks abroad unchecked in the midst of a British population, and under the very walls of a British fortress.

Not everyone shared his views on crimping. Some resented Henry airing the seamy side of Quebec maritime life in the pages of London’s foremost newspaper. “Writing letters of complaint to newspapers is a very common way of evading duties,” declared the Quebec Mercury in an editorial critical of Henry’s letter to the Times.[6] The Mercury declared that the city’s crimping was no worse than in other major ports around the world. The newspaper blamed the stinginess of merchants like Henry for Quebec’s insufficient supply of seamen. The ship-owners and masters could easily arrange to bring able-bodied sailors from England to meet the crewing needs of outgoing ships. “Neither seamen nor crimps are responsible for the existing state of affairs,” stated the Mercury. “The remedy must be applied by the mercantile community.”[7] Easier written than done, however.

Crimping wasn’t the only trouble on Henry’s mind. The international economy was in a swoon. The price of deals (sawn softwood timber, typically a thick plank of pine or spruce) had fallen by half since 1854, and ships and freight by almost as much. “In 1857 came the Indian Mutiny [leading to the collapse of the East India Company] and terrible panic,” he wrote.[8] “Five English and Scottish banks failed. The panic in the U.S. was also severe.”

Henry had been half owner of the sailing ship Hinda since the late winter of 1854. Already burdened by paying interest on the original purchase price, he now faced the fact that the ship’s value had plummeted, an early victim of steam’s superiority over sail.“The Crimean War was winding down,” he wrote, “and the British government was chartering steamships, rather than sailing ships, to bring the troops home.”

He decided to sell his half of Hinda to the Bristol pawnbroker Cole who owned the other half and was managing her. “Owing to a petty act of attempted fraud on his part, I sold the other half to him at a sacrifice, losing on the whole, some £600.”

While the worldwide depression disadvantaged Henry as a seller, he could now buy cheaply. In the spring of 1857, the sailing ship Lotus was for sale in Bristol. He saw her as a large ship admirably suited for the Quebec trade, although sixteen years old. “As I had not the means to pay for more than one-quarter of her, I induced Mr. Yeo to take 1/4, and two very dear friends, Captain Joseph Samson and Mr. R.S. May, consented to take 1/4 each. So we bought her for £3,900.”[9] As for his own share, he appears to have bought it mostly with other people’s money, notably $25,000 from the munificent William Yeo in Devon.

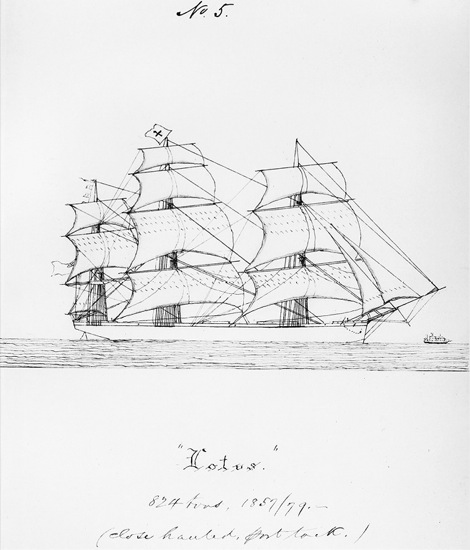

The three-masted, 841-ton Lotus had been built in 1841 at Saint John, New Brunswick, primarily of spruce and birch. Soon after the purchase, Henry wrote, “Captain Samson and Mr. May both died, and I bought their shares from their Executors, and ultimately Mr. Yeo also.” Henry got her profitable work carrying rails and coal, and over the next nine years Lotus cleared him a profit of about $35,000.[10]

In December 1856, he had travelled from Boston to Liverpool on the steamer Canadian with his twenty-year-old sister Lucy, who was visiting Canada. It was a violent voyage. In a storm off the northwest coast of Ireland, Henry recounted that he “saw the 1st officer washed off the bridge, five lifeboats smashed, [and] the ship’s gun hurled into the engine room.” It was hardly a singular accident. During the seven years, 1854–1860, when Henry crossed the Atlantic a dozen times, as many as two thousand unfortunate men, women, and children tragically lost their lives in Atlantic steamship catastrophes. The year 1854 alone saw the loss of as many as eight hundred lives, more than half the number who would go down on the Titanic. For example, the City of Glasgow left Liverpool in March for New York, with 480 persons aboard, and was never heard from again. The same year more than three hundred passengers and crew perished after the American Collins Line’s steamer Arctic collided with another ship in the fog off Cape Race, Newfoundland, and sank. On board the German steamer Austria in 1858, an officer trying to fumigate the steerage quarters caused a fire and the loss of all but 67 of the 538 persons on board.

Using other people’s money: Built in Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1841, the sailing ship Lotus was in Bristol Harbour when Henry bought her, mostly with borrowed funds. After arranging cargoes of rail and coal, he was able to repay his lenders.

Pen-and-ink illustration by Henry Fry, 1891.

Henry’s wintertime transatlantic crossings were often brutal. He was aboard Cunard’s steamship Canada travelling from Boston to Liverpool in December 1857 when a hurricane from the southwest struck the ship off the coast of Ireland, tossing the pathetic passengers about for twenty-six hours in “awful” seas. When he returned four months later, again on the Canada, the ship ran into a violent gale and thick fog and nearly went ashore on Sable Island off Nova Scotia.[11] Transatlantic autumn and winter ocean travel was unpleasant at best. Statistically, you put your life on the line each time you crossed. Henry did it repeatedly.

In England he worked out of Bristol, and likely travelled to London on business. He assuredly spent time with family. His father, George, was seventy-four years old, and would live another eleven years. His youngest brother, Edward, was fifteen. Perhaps Henry went down to Winscombe to see the old family farm. Not far away in Devon he discussed his affairs with William Yeo.

Yeo, in addition to partnering with Henry in ship investment, took a paternal interest in the younger man, and may have asked Henry, now age thirty, if he intended to marry. Similarly, friends and family in Bristol good-humouredly asked if he intended to cling to his bachelorhood. But only five years had passed since his nervous breakdown. Inwardly, he worried that he might be a burden to a bride, a failure as a father.

A keen book purchaser, Henry knew Samuel Edward Dawson, the Montreal book dealer. Henry and Sam also shared an interest in the St. Lawrence River. The Dawsons, like the Yeos, were originally a Prince Edward Island family. Sam had a younger sister, Mary Jane. Nothing is recorded about how Henry met Mary, but meet her he did. It may have been a socially daunting experience for Henry to visit the Dawson home in Montreal. The Dawsons possessed an impressive lineage. Mary Jane’s mother, Elizabeth Cobb Gardner, was a descendant of Richard Warren, who’d arrived in America on the Mayflower. The family was descended from Thomas Dawson, who fought under Cornwallis in the American Revolutionary War, then returned to Ireland. In 1801, Thomas took his family to Prince Edward Island where he purchased six hundred acres of farmland. He achieved notoriety on the island as a fiery preacher and fanatical Methodist.

Mary Jane and her eight siblings were well educated at schools in Halifax and Montreal. The most talented was her brother Samuel Edward, who would become a close friend of Henry and executor of his will. Together with his brother, Sam expanded the family business, which embraced book publishing and retailing, stationery, and newspaper and periodical agency operations. He later left the business to write books, including a history of the St. Lawrence River, and he was an expert on copyright law, becoming Queen’s Printer of Canada.[12]

The woman Henry proposed to bore herself impeccably. She was relatively tall for a young woman of the mid-nineteenth century, about five feet seven inches. She had a finely sculpted, thin face with childlike eyes. Nothing was juvenile about her actions, though. Mary Dawson in her long life would prove to have a sharp eye for real estate and investment. Her 1858 marriage contract today would be called a pre-nup. The contract may have been engineered by her father. In later years she used it to advantage. Not only was there total separation of property, but she brought no dowry to the marriage. Quite the contrary, a condition of Mary marrying Henry was that he give her $4,000 (about $83,000 today)[13] to be invested in her name.[14]

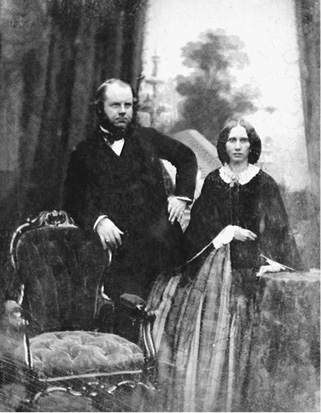

Henry had found himself a superb partner … a slender beauty, twenty-two, whose parents had roots in the Maritimes and pristine New England, and a family name traceable to eleventh-century Norman nobility. The bridegroom, ten years older, was a fine-cut exemplar of the Anglo Saxon race, outgoing and already a business success.

On December 9, 1858, Henry and Mary were married in old Montreal in the St. James Methodist Church. Where else? The Dawsons were fervent Methodists. Behind the church’s high Gothic towers fronting on St. James Street, the ceremony took place. Benjamin Dawson, Mary Jane’s father, was present to give away the bride. Best man was Henry Dinning, the Quebec shipbuilder. Mary’s wedding dress, which today is preserved in the Nova Scotia Museum in Halifax, was a wide-necked affair of ivory silk taffeta, with boned bodice, pagoda sleeves, and a two-tier skirt gathered all around into a pointed waist.[15]

It remained now for Henry and Mary to settle the matter of their religious affiliation in Quebec. If he had surrendered to the formality of a Methodist marriage, she should surrender to formal registry in the Quebec Baptist Church. Mary agreed, but with a certain lack of grace. Later, after taking up residence in Quebec, she refused to submit to immersion, evoking a protest from a congregant, Mr. McFarlane. Henry was the little church’s most generous financial supporter. The protest was ignored.

A few days after the wedding, accompanied by Henry’s sister Lucy, who’d come from England on his sailing ship Ant to serve as a bridesmaid, the couple travelled by train across snow-covered New England to Portland, where they boarded the steamship North Briton for Liverpool. After an eleven-day crossing, they sped down to Bristol, where Mary encountered for the first time Henry’s parents and the rest of his siblings.

As a honeymoon — crossing the storm-tossed North Atlantic and wintering in England where Henry carried on business — the four-month trip fell disappointingly short of, say, a sojourn in Bermuda. But the new husband compensated his young wife. They spent time in London, and here Henry commissioned the celebrated artist Edmund Havell, portraitist of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, to do a head-and-shoulders watercolour of Mary, a delicate oval shape placed in an fine square gilt frame.[16] In the portrait Mary wears an exquisite broach of solid gold leaves floating on a twisted coil of gold tubing, with a spectacular oval aquamarine in the centre, plus matching pendant earrings, wedding gifts from her new husband.[17]

In April 1859, Henry and Mary re-crossed the Atlantic on the same steamship that had brought them to England … this time thrilled by seeing forty icebergs off the coast of Newfoundland. Back in Quebec, they moved into a rented cottage on the Plains of Abraham, above the ravine that British troops scaled on the night of September 12–13, 1759. Henry partly furnished the cottage with tables, chairs, carpets, glassware, cutlery, and art that he’d transported on the Ant from London. Even as a bachelor, he’d collected marble vases, a marble clock, cigar stand, bagatelle board, port and sherry glasses, statuettes of historical figures, a Brussels carpet, and a black sheepskin rug.

Henry and Mary were now living next to the site where a hundred years earlier men had fought the battle that shaped the future of North America’s political boundaries.

Newly wedded: Henry Fry and Mary Jane Dawson, after marrying in December 1858 in Montreal, visited the recently opened studio of pioneering Scottish photographer William Notman. His camera captured their image in a rare early photographic process known as ambrotype. The glass surface has become slightly scratched over 150 years.

Photograph by William Notman; courtesy of Dick Avison.