15

MARIO ANDRETTI

Won Indy 1969

Date of interview: October 2015

The three-time United States Driver of the Year discusses the first time he ever saw the Indy 500.

IT DOES start with a dream. I came to the States when I was fifteen years of age. My dream was in place. I had no idea how I would pursue it.

Two years later, my brother Aldo and I, my twin brother, we got together with a couple of other buddies and we started building a car. Fast forward to 1958, when an uncle of ours locally here, after listening to Aldo and me express ourselves about racing and so forth, he took us to Indianapolis.

Wow!

That was my first experience seeing the place, and I was eighteen years old. The car that we were building was almost finished. We arrived there and stayed right there at 16th and Georgetown. It was like a trailer park. We slept in the car. We had good seats, pretty much at track level at turn four. As we watched the race, at one point I said, “I’m gonna be here someday.” It was much like when I was in Italy watching the Italian Grand Prix at age fourteen and I said: “I’m going to be here someday.”

WHEN DID YOU START GOING FAST? DID YOU ALWAYS HAVE AN ATTRACTION TO SPEED?

We had a ’57 Chevy and we would just tool around. We got up to 120 miles per hour—as fast as that thing would go. We got in trouble a few times. We would rule the neighborhood—I can tell you that!

But what the heck, it’s not racing until you actually get on the racetrack. You’re not really experiencing it. That started when I was nineteen.

My brother and I used to do everything together. Aldo and I both had the same dream. Unfortunately, for him, he was injured very badly at the end of the very first season in 1959. It was an invitational, the last race of the season. After the accident he took a sabbatical. A year later he came back and raced for ten more years.

The great Indy figure Andy Granatelli (R.I.P.) is in the hat. The jubilant sponsor of the #2 STP Oil Treatment Special once famously planted a congratulatory kiss on Andretti’s cheek as he climbed from the racer. A photographer captured the moment and soon all the world would see it, long before the word “viral” found its current use.

In ’69, the week after I won Indy, I had a race in Milwaukee and he was in Des Moines, Iowa, racing a sprint car. That was going to be his last race. He had another big accident and that ended his career.

Then his life changed. He was laid up for a year. He went on to raise a family, start a business, and live with his family in a normal way. He was supportive of us but never raced again.

Aldo now has a “third generation” driving as well. His son John, John Andretti, has started at Indy, drives NASCAR. He’s a great driver. John’s son Jarett drives sprint cars now. I have the third generation on my side with Marco, Michael’s son. The family continues life in our sport. It’s really the only thing we know.

Mario’s grandson and Andretti Autosport racer Marco Andretti.

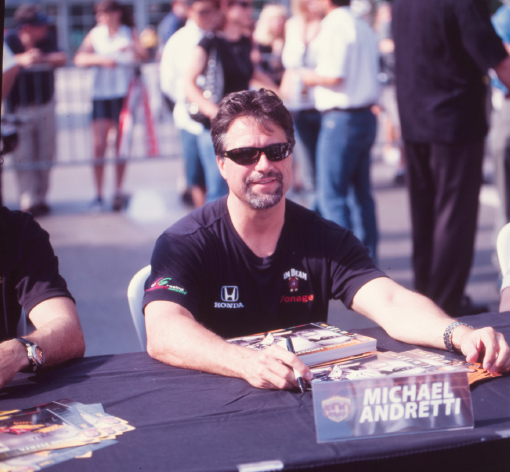

Mario’s son (and Marco’s father) Michael Andretti.

ON HIS ARRIVAL TO INDIANAPOLIS AS A ROOKIE:

I got out of driving stock cars at the local level—got into midgets and sprint cars in 1963 and ’64. When I got to the USAC level in sprint cars and I won some races, that’s where I got picked out to try a Champ Car, by the Dean Van Lines folks. They had Clint Brawner—he’s the one who gave Foyt his driver’s test at Indy. Eddie Sachs and Jimmy Bryant were driving for that team. These guys were icons.

I was invited to run some Champ Car races in ’64, after Indy. Actually, I was hired before Indy, but Clint Brawner didn’t think I was ready, so he told me: “I’ll have you in a car right after Indy”—in the “Hawk.” That was it. I started and then ran the rest of that season. I qualified [for the 1965 season] as a rookie. That next year, my first race in a rear-engine car was exactly at Indy. I had never as much as sat in one before. Up to then I drove a roadster—really, one of the latest design roadsters—nice lines. I did well with that. Then, my debut with the rear-engine car happened. I took to it like a duck to water. I was in my element immediately. The car arrived at the track [Indy] a week late. Others had already been practicing a whole week. In those days you could take the driver’s test up until Wednesday of the second week of May, which was the week of qualifying. My car arrived exactly on that day. I was “on track” that Wednesday. I got my test and passed with flying colors. I finally stopped biting my fingernails.

As a teenager, before he became the experienced Indy veteran he is now, Marco receives some trackside wisdom from grandfather Mario.

Can you imagine . . . me, no car, and everybody else is running around learning what to expect. I’d never even been on the track before, not even in a pace car. The first time I got on the track was in a race car.

Well, it’s one of those things—you just gotta do it. When you get on the dance floor, you gotta dance! Anyway, it felt really right at home—me being at Indy. I had that mindset: just stay positive, just stay positive that everything would work out.

Luckily, everything was right. I was certainly with the right team with Clint Brawner, who’d seen it all. Clint had an assistant, Jim McGee, now known as one of the all-time great crew chiefs at Indianapolis. It was a seasoned team. I had the best of all possible worlds going for me. You cannot do it alone.

In ’69 when I won I had the same team. I had really good luck and good times at Indy. In ’65 I sat in the second row and finished third. In ’67 I was on the pole! I could have won two of the easiest races of my life—and both times the cars had mechanical failures. In ’68 we had a new engine—a Ford engine. It was a mistake—the thing blew up on the first lap.

Don’t forget that in ’65 I won the National Championship, as well. I was the youngest driver to do that. In ’66 I also won the championship. In ’67 and ’68 I finished second in the championship. I would have had five straight championships. In ’69 I did win my third championship. I won that one in August; the last race of the season was in December, so I really had a great year.

Sixty-nine was the only race I finished at Indy since my rookie year. I felt very comfortable. Indy was the first place that I felt that I knew how to drive. I love the place. The thing that was to my advantage was the team. Dean Van Lines had a solid relationship with Firestone. They were the Firestone “team of choice.” Firestone was also looking for some fresh input. You know, they had all of the seasoned drivers like Parnelli Jones and Rodger Ward—drivers like that doing a lot of the “development,” but they felt that they needed some new fresh input. Sometimes “adventurers” have a way of doing things, explaining things. They wanted to have this on the team of their experienced drivers, and I happened to be the one. Because of that I was getting a lot of “testing.” I was driving thousands of miles of testing. Indy was one of their places. I was breaking records testing; I knew every crack on the track and I still do today.

Indy, as symmetrical as you think the track is, is very fickle. Don’t take anything for granted. Every corner is absolutely different. With speed, the faster you go the more the difference magnifies. The wind factor is huge. The wind is going to blow differently on every corner. If you don’t think you need to compensate, well, think again. That’s why there are two flags. When you go down the straightaway, up on top of the pylon there’s a flag; you can see which way it’s blowing, and compensate. You go down the back straightaway, it’s right in front of you on the grandstand. In turn three there’s another flag that you watch, that you better pay attention to. So the bottom line is when you’re really “at the limit” at Indy, believe me you better know what you’re doing and what to expect. Like I said: It’s not as symmetrical as you think.

The banking is only nine degrees. It’s relatively flat compared to some of the oval that we run. Because of that, obviously, the onus is on the driver a lot more. You have a tendency to “drift” more when you don’t get the banking “help” in the corners.

Of course we now run “flat” all the way around the track. You’re going 235 or 240 down the straightaway—that’s the way you enter and go through the turns in qualifying, not in the race.

G-forces? In qualifying we’ve seen 5.2.

When I was racing, in Michigan, for instance, when I qualified at 234.7 average on a one-mile track, I had 6.2 g’s measured.

Obviously, you brace yourself. You make sure that your seating arrangement and everything else is really, really tight. You must fit like a glove. You must be strapped in very, very tight. You have “side support.” You can’t turn the wheel; you just try to hang on. Your body is being slammed to the side, and it feels six times heavier due to the G-forces. That’s what people don’t understand. That’s why it’s so important to fit yourself really, really well in the car, in the seat. At that speed you also have to be able to feel. Get the feel of the car—which side is shimmying or giving up; you don’t want to lose anything. At the same time you have to be comfortable enough that you can steer the damn thing.

The relationship between drivers and engineers is the same as patients and doctors. I’ll give you an example: the driver is the patient. The patient goes to the doctor and says, “Doc, here’s where my problem is. I hurt here, here, there.” So the doctor goes right to the point.

If you go there to the doctor and say, “Doc, I feel like shit. I’m hurting all over. I don’t know where it is.” So what’s the doctor going to do? He’s going to put you through tests and . . . God knows. So when a driver comes in, the more detail he can explain [regarding] what the car is doing, the easier it is to go to the “fix.”

If you come in and say, “You know what? This thing is a piece of crap. I can’t make heads or tails of what is going on,” what is the guy going to do? Where does he start fixing?

That’s where teamwork makes a difference. Being able to get it right and getting results . . . and not.

You hear this all the time: “I really, really gel with my engineer (or crew chief); we really understand each other.” That’s what it’s all about; that’s where teamwork comes in. A lot of people don’t understand how important teamwork is in our sport. You know, the driver is usually either the hero or the goat.

The best driver in the world cannot produce miracles if the equipment is not “capable.” You cannot do what the equipment is not capable of doing—you’ll kill yourself.

You need to have the team around you. In a race, the team that “services” you, they can make it or break it. Personally, I’ve grown lifetime friendships with mechanics and others that I’ve worked with over the years. We’d created a real camaraderie. They knew that I was out there bustin’ my butt [100 percent]. They gave you ten-tenths as well. We inspired one another.

Mario Andretti was spotted as he walked from the Andretti Racing garage in Gasoline Alley, prior to being besieged by fans seeking an autograph. He’s prepared, with a pen in hand.

Win or lose, we do it together. No one ever had more appreciation for the team than I did.

THE ANDRETTI DYNASTY OF RACERS?

Let me tell you this: This is the business we know. The only business we know. When the family is together we bore the hell out of the ladies. Christmas dinner? We talk about racing.

The bottom line, what I have found is, from my standpoint. I cannot teach young drivers to go fast. That has to come from inside. From your belly. The only suggestion I can make is help them to minimize mistakes. That’s the only thing I can contribute.

If I had to do my career over again, I guarantee you there are a few things that I would do differently. Perhaps I can point out a few “shortcuts” away from potential mistakes.

Personally, I have no regrets, believe me. No regrets and I count my blessings every day. But if I had to do things all over, some of the mistakes I made, like being too “exuberant” the first lap and stuff like that—I wouldn’t do those things again. I would be more patient.

You know, you learn from mistakes, for sure. That’s where I feel I learned, because I made plenty of them [laughs].

I made every mistake ever made. As time goes on, that’s what you strive to minimize, through experience. That’s the contribution I feel that I could have for younger drivers. If they ask a question you give an honest answer. They have to ask the question. It’s the same thing with my grandson. I don’t volunteer unless they ask the question. Sometimes when you “volunteer” they take that as criticism. Not constructive criticism—they can take it as just criticism. I’ve learned that. Then they resist you.

So now I say, “Okay, I’m there if you need me. You want an opinion? You just want to pick my brain a little bit? I’m there a hundred percent for you.”

The author had lingering questions concerning the ’57 Chevy that the Brothers Andretti shared as teens.

Mario kindly responded the following day:

Q: What color? A: Red with white top

Q: Body type? A: Bel Air 2-door hard top

Q: Engine? A: 283 Duntov cam, 4 barrel carburetor, stick shift

Q: Had the boys modified it in any way? A: Added glass pack muffler