CHAPTER ONE

SELECTING MATERIAL FOR THE BLOCK

HE CHOICE of block material varies from artist to artist and from image to image, depending on the style and technique the artist plans to use. Although I prefer carving into the warm organic surface of wood, other artists cut their images into plastics, soft metals, combinations of materials, and even found objects.

HE CHOICE of block material varies from artist to artist and from image to image, depending on the style and technique the artist plans to use. Although I prefer carving into the warm organic surface of wood, other artists cut their images into plastics, soft metals, combinations of materials, and even found objects.

The sketch plays an important part in determining which material you choose. Sketch out your design, then consider the following:

u Will your image be finely detailed? Some materials offer a better surface for detailed work than others. Hardwoods, for example, hold more detail than softwoods.

u Do you want the wood grain to show in your final print? Knots and coarse grains can fight with an image if they appear in the wrong place, or they can enhance an image by providing an interesting background. Edvard Munch, the great Norwegian artist, used the texture and imperfections of the wood grain to great advantage in his work. In the contemporary woodcuts of Helen Frankenthaler, Ralph Steadman and Antonio Frasconi, the grain also forms a vital part of the image and is carefully considered before the work begins.

If a strong grain appeals to you, the grain in a birch-faced plywood can be roughened with a wire brush to enhance the effect. If you don’t want the grain to show, you might choose a maple block with a smoothly sanded surface.

u How large will your final image be? The printing method you will be using and the paper sizes available will help determine the dimensions of your work. A lightweight material – luan plywood, for example – is a good choice for working large, because it is easy to turn when you’re cutting curves into its surface and takes up less space on your storage shelves than heavier materials.

u How much money do you want to spend? Specialty woods such as cherry and basswood can cost 10 times as much as plywood.

u Are you going to buy the blocks ready-made or make them yourself? Local art supply stores sometimes carry small pieces of wood and linoleum for printmaking. You can also make your own wood blocks (see pages 35 and 37) or have a carpenter make them to your specifications.

A favorite wood of woodcut artists is basswood, because it has fewer knots and does not warp as easily as pine. Wood engravers prefer maple and boxwood because of their tight end grains. And cherry, the choice of those who practice the traditional Japanese style of wood-block printmaking, is used on the plank for woodcut and on the end grain for wood engraving. By experimenting with small pieces of wood or alternative materials first and by looking at prints made from different types of blocks, you will find the material that best complements your own style of work.

MATERIALS FOR WOODCUT

Softwoods

Many artists like softwoods – pine, fir, spruce and cedar – for woodcuts. They are less expensive than hardwoods and are believed to be easier to carve, although it’s worth pointing out that pine can be harder than basswood.

If you are looking for a wood with knots and a strong grain, pine is ideal. The flat planks found in old pine furniture (the poorly designed pieces even your grandmother would have thrown out) make excellent candidates for blocks, because the wood has been seasoned for a long time. Spruce planks that have been planed and sanded flat are a good choice for those who prefer an unmarked surface.

Hardwoods

Maple, cherry, poplar, basswood, hornbeam and other hardwoods provide a hard block surface that holds details well. The disadvantage? Tools need to be sharpened frequently and, if your hands aren’t strong, the extra pressure needed to cut into the surface can be a challenge. With practice, though, your hands will become stronger. You can also try rubbing a small amount of sesame cooking oil into the surface to make it easier to carve. Once you’re used to cutting hardwood blocks, your reward is a strong, durable surface from which to print.

Basswood is a good choice for beginners because it has fewer knots than pine and doesn’t warp as easily. Although it is expensive, cherry is especially nice, and the final block can be as beautiful as the prints made from it.

Secondhand oak or maple furniture is a good source for seasoned plank hardwood. Painted, stained or varnished planks can be restored with a belt sander and squared up with a table saw. They can also be left with their original finish intact. Be sure to check the surface, though, for old nails and hardware; they can damage your tools.

Plywood

Plywood panels are made by gluing together thin layers of wood, called plies, with the grain direction of each layer at right angles to the previous one. The outer plies are known as the front and back faces and the inner plies are known as the core layers. The greater the number of plies, the flatter, stronger and more expensive the plywood will be.

Good grade plywood provides a flat, smooth surface for carving. Plywood is graded A, B or C according to the quality and appearance of the veneers used for the outer faces. These grades can be applied to one or both sides of the plywood. You can get away with A–B plywood – grade A on one side and B on the other – for woodcuts that will be printed on a press, because only one side of the block is carved and printed. (Carving both sides would make the block unbalanced and difficult to print.) Even if you’re interested in a textured grain, it is still best to choose grade A plywood and then roughen the grain with a wire brush.

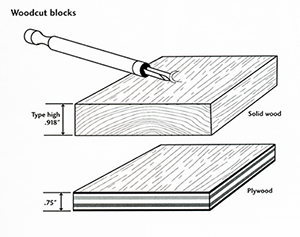

Plywoods are available in a variety of thicknesses from 1/16 to 1 inch. The thinner thicknesses (below 1/2 inch) are usually found only in hobby or art supply stores. The standard sheet size is 4 x 8 feet and is commonly 1/2 or 3/4 inch thick. For printing on a letterpress, the plywood must be 3/4 inch thick and then built up with a few sheets of bookbinders’ board or mat board to bring it to type height (0.918 inch, or about 15/16 inch). For printing by hand or on an etching press, the plywood can be as thin as 1/8 inch. The thinner plywood is easier to handle and organic shapes can be quickly cut into it with a scroll saw or jigsaw.

A large sheet of 1/2-inch plywood purchased from the lumberyard is the cheapest way to make a big woodcut. I like birch-faced plywood because it has a strong surface veneer that will not dent or mark

easily while you are cutting it. Other artists prefer poplar-faced plywood because it has a softer face veneer. Although this makes it easier to carve, it is easily dented if you accidentally drop something on its surface.

Shina plywood is a favorite of artists working in the Japanese printmaking style but can also be used in Western-style woodcut printmaking. Because it is manufactured with a basswood face and a basswood or mahogany core, shina can be cut like a solid plank of wood, is easier to carve across the grain than plywoods with layered plies of different hardnesses and, not surprisingly, is more expensive. It comes in a variety of thicknesses, the most common one being 3/8 inch, and in sizes ranging from 36 x 48 inches down to as small as 4 x 6 inches. Shina can be carved on both sides if printed by hand and is available from art supply stores, hobby stores and Japanese woodblock suppliers.

Aviation-grade plywood, which is faced in either birch or mahogany, is strong and light with a noticeable grain. Model aircraft supply stores sell it in 3 to 12 ply and in very thin sheets, although more than 1/8 inch thick is the most useful for printmaking.

American abstract expressionist artist Helen Frankenthaler uses the lightweight luan plywood, made from a Philippine mahogany, for her large woodcuts. Its soft face is easy to cut into and its nearly straight grain provides interesting backgrounds and textures, although it is susceptible to splintering. Luan is available in 3-ply, 1/4-inch thick planks. It prints lovely unblemished flats of color with a fine, even surface grain showing through.

A light wash of diluted PVA (polyvinyl acetate) glue applied over the surface of a plywood block makes it easier to cut and reduces splintering. (This trick also works on plank-grain wood blocks.) Splintering occurs when the cellulose fibers in the grain lift out during a cut, leaving a chipped edge to the line. This happens most frequently in cheaply made plywood, which is why you should always buy the best plywood you can afford.

Particleboard, Chipboard and MDF

Particleboard, chipboard and MDF (Medium Density Fiberboard) are really not suitable for woodcut printmaking. Particleboard’s extremely rough surface, and the type of glue used to manufacture it, make it difficult to cut into. Cutting into MDF board leaves a burred edge of raised fiber particles on the line. And the surfaces of all three will dull the keen edge of any tool. However, if you plan to carve shapes with a jigsaw and you like a textured surface, any of these low-grade boards can be used. They can also be cut with rotary power tools, but since these materials tend to chip unexpectedly, be sure to wear safety goggles.

Lino blocks and pieces of plastic are sometimes mounted on these boards to bring them up to type height for printing on a press or simply to make them easier to handle when cutting.

Linoleum

Linoleum is a composite flooring material made by spreading a mixture of powdered cork, rosin and linseed oil onto a backing. Battleship linoleum is the traditional material for linocut. Flooring stores sell it in huge rolled sheets, but smaller mounted or unmounted pieces can be found in art supply stores.

Linoleum provides an ideal surface for the beginner because it is cheap, relatively flat and readily available. Before it can be carved, though, the surface coating must be removed by sanding it lightly with a fine grade sandpaper or steel wool. To make cutting the lino easier, warm it on a warming plate or with a hair dryer. You can also put it in the microwave for 30 seconds – any longer and it will bubble – to soften the surface. To make it easier to print, many printmakers mount the lino onto 3/4-inch plywood or particleboard using PVA glue.

Linoleum tends to dry out and become brittle with age, making it more difficult to cut. The surface can be somewhat restored by warming it and then rubbing a light linseed oil into it.

In addition to linoleum, printmakers have tried other flooring products with mixed success. Many smooth-surfaced vinyl and composite tiles can be used if they are at least 1/8 inch thick. You’ll have to experiment with these. I’ve seen both good and bad results.

Rubber and Styrofoam

A popular inexpensive alternative to the harder materials listed above are rubber and Styrofoam. These materials are very popular with teachers who wish to introduce relief printing to younger students in a classroom setting. Styrofoam and rubber are never printed on a press because they tend to compress easily, thus losing the relief you intend to print from. The Styrofoam used for insulation is the best choice, and is available from most hardware and building supply stores. For rubber you can use erasers, or for larger work a product known as Softoleum (1/4" thick). There are many other rubber brands for carving such as Speedball Speedy Cut (3/8" thick), Steadler Mastercarve (3/4" thick) and Soft-Kut (3/4" thick), all available from art supply stores. They sell for between 6 cents and 50 cents a square inch. Rubber and Styrofoam are usually cut with the Speedball cutter, but any of the woodcutting gouges, parting tools or a knife can be used. Because these materials are so soft they are sometimes printed with a stamp pad, the kind used for printing rubber stamps.