1 Yellow journalism. For years, people have felt that the term “yellow journalism” was derived from the rivalry between publishing moguls William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, and their tendency to sensationalize rather than report news. However, the term did not originate with that practice—people had already been criticizing Pulitzer and Hearst for those theatrics for years before “yellow journalism” became a buzzword, using the derisive term “new journalism” to describe their practice. The usage of “yellow journalism” specifically came about when Hearst, in 1897, began featuring the popular comic Yellow Kid on the editorial pages, mixed in with actual news. New York Press editor Elvin Hardman found the idea of mixing cartoons with news highly offensive, and it was this that he used to knock Hearst, suggesting that the mix of information and entertainment was not a good sign for the sanctity of newspaper journalism. Hardman’s term was quickly picked up by the other critics of Hearst and Pulitzer, and so a term was born!

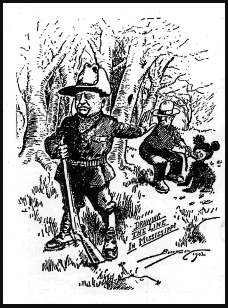

2 The teddy bear. In November 1902, Theodore Roosevelt, president of the United States and avid hunter, went on a bear-hunting trip while he was in Mississippi. Figuring that it would look good for the president to kill a bear (animal rights were not an issue at that time, clearly), Roosevelt’s aides found a young black bear and, after clubbing it nearly to death, managed to tie it to a tree. They informed the president that here, here is a bear you can kill! Roosevelt was disgusted at the unsportsmanlike nature of the notion and refused to shoot it (although he did tell his men to put the animal out of its misery). The news of Roosevelt’s decision made its way back to Washington, DC, and legendary political cartoonist Clifford Berryman produced a cartoon that would become famous all throughout the United States, being reprinted in many newspapers. Titled “Drawing the line in Mississippi” (a play of words on the border dispute Roosevelt was there for), the November 16, 1902, cartoon depicts Roosevelt choosing not to shoot a cute little bear.

Berryman began to make the cute little bear his shorthand symbol for Roosevelt, using it in all of his cartoons about the president. The cartoon bear inspired a candy shop owner named Morris Michtom (who would often make little stuffed animals with his wife to sell in the store) to begin selling a stuffed bear toy (after receiving permission from Roosevelt) as “Teddy’s Bear,” which, of course, became known as a teddy bear and soon became one of the most popular toys in the world.

3 The names of the Marx Brothers. At the turn of the twentieth century, Charles Augustus “Gus” Mager was working on a funny animal strip called Knocko the Monk, starring a group of anthropomorphic monkeys called “Monks.” Each of the Monks had a nickname to differentiate them from one another, and they would invariably end with an “o”: Rhymo the Monk, Henpecko the Monk, Groucho the Monk, stuff like that. Around the same time when the strip took off, the Marx Brothers were just starting to gain attention with their vaudeville act. While playing poker with the brothers, fellow vaudeville performer Art Fisher began to come up with “o” names for each of the brothers, based on various facets of their personality, Harpo (played the harp), Chico (he got lots of “chicks”), Gummo (something to do with shoes), and Groucho (people aren’t actually sure exactly why he was called Groucho at the time). The names stuck, and the brothers soon became national stars.

4 Back to the drawing board. The New Yorker has always matched the cultural zeitgeist with its famous cartoons. A 1928 cartoon by Carl Rose (with a caption by E. B. White, later writer of Stuart Little and Charlotte’s Web) turned “I Say It’s Spinach” into a national catchphrase! But for adding to the common vernacular, it’s hard to compare to Peter Arno’s 1941 cartoon of a man reacting to a plane crash by simply saying, “Well, back to the old drawing board!” Naturally, the phrase became popular and now “back to the drawing board” is such a common phrase it is hard to believe that it ever was not a turn of phrase, let alone that it came from a cartoon!

5 Sadie Hawkins Day. Alfred Gerald Caplin, better known as Al Capp, began his legendary comic strip Li’l Abner in 1934. The series follows the misadventures of a group of hillbillies living in the poor town of Dogpatch, Kentucky. While the strip is an ensemble, the titular character is Li’l Abner himself (who is, in fact, quite a big guy). One of the recurring plots in the comic is how a beautiful girl, Daisy Mae, desperately wants to marry Abner, but he is routinely either oblivious or downright not interested in commitment. In a 1937 strip, Capp introduced an interesting concept—Sadie Hawkins Day! The idea was that the founder of Dogpatch had a daughter no one would marry (Sadie Hawkins). So he declared “Sadie Hawkins Day” and all the bachelors in town had to run all day and if Sadie caught any of them, they would have to marry her. It was clearly intended as a one-off bit, but the idea was such a massive hit that Capp was “forced” to make Sadie Hawkins Day a regular occurrence in the strip and poor Abner had to outrace Daisy Mae every year. Li’l Abner was a successful strip right out of the gate, but when Sadie Hawkins Day debuted in 1937, the strip was in the midst of a boom in popularity—all of these new readers soon got quite attached to the Sadie Hawkins idea (the popularity of comic strips during the 1930s would be similar to that of television series today). Just two years after the original strip, Sadie Hawkins Days were popping up on college campuses all over the United States. Even after Capp had Abner and Daisy Mae get married in the early 1950s, the Sadie Hawkins Day strips continued. Nowadays, Sadie Hawkins Day mostly survives through the use of the term in reference to school dances where the girls are the ones who ask the boys to the dance.