Chapter 16

Shakespeare with a Difference: Dismembering and Remembering Titus Andronicus in Heiner Müller’s and Brigitte Maria Mayer’s Anatomie Titus

Pascale Aebischer

Der Text das Messer, das den Toten die Zunge löst auf dem Prüfstand der Anatomie; das Theater schreibt Wegmarken in den Blutsumpf der Ideen … DISMEMBER REMEMBER

('The text as knife, which loosens the tongue of the dead under the microscope of anatomy; theatre writes path marks in the blood swamp of ideas … DISMEMBER REMEMBER')

(Müller 1989a, 224–25; 2012, 171)

The study of early modern drama in performance is divided between those who consider the plays within their own historical, literary, and theatrical contexts and those who concentrate on how the plays are produced and made to signify in constantly changing and context-specific ways in later periods. It is the latter approach which is modelled in this chapter. It adopts Margaret Jane Kidnie’s view that the early modern play

for all that it carries the rhetorical and ideological force of an enduring stability, is not an object at all, but rather a dynamic process that evolves over time in response to the needs and sensibilities of its users.

(2009, 2)

Kidnie helpfully describes both scripts and performances interchangeably as 'production(s) of the work', which 'continually takes shape as a consequence of production' (2009, 10, 7). My focus on two productions of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus – one a radically repurposed playtext, the other a touring digital video installation – that talk to each other across the historical divide of the 1989 collapse of the East German regime considers the personal and political pressures Titus’s modern adaptors exert on a work which is ever more starkly dissected and reconstructed in the image of the present, pushing to an extreme the notion of what the title of this Companion volume terms 'the production of early modern texts' might mean. As Shakespeare’s pre-text of violence and cannibalism is anatomized and reassembled, it becomes a work that speaks of the decline of Western civilization, its threatened overthrow by former European colonies, and the ways in which the Western culture of consumption is predicated on the sacrificial starvation of its daughters.

Brigitte Maria Mayer’s Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome (2009a) is a high-definition digital video installation based on her late husband Heiner Müller’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus as Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome Ein Shakespearekommentar (GDR, 1985; reprinted in Müller 1989a). The installation toured from its première at Berlin’s Akademie der Künste in 2009 via Le Reemdoogo in Ouagadougou, the Shizuoka Performing Arts Center in Japan, and several stops in Los Angeles, to Bern’s Zentrum Paul Klee and eventually to the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris, where the installation was shown in 2012. Filmed on location in China, Egypt, Syria, and Ghana, Mayer’s installation counters Müller’s, and Shakespeare’s, fragmentation of the female body and Lavinia’s marginalization within their texts with her own fragmentation of their texts.

By setting Müller’s words in a twenty-first-century historical context and a different medium, Mayer 'translates' his play in much the same way that Müller understood his own play as a 'translation' of Titus Andronicus for the 1980s: 'The more you change a text, the more it is the same … You cannot translate words; you have to translate a whole context' (Müller 1998b, 190). For Müller, during the final years of the totalitarian regime of the GDR, the context for Anatomie Titus was inevitably political, with Shakespeare lending authority to Müller’s vision of the dialectical forces of history. By the 1980s, Müller was widely recognized as a 'symbolic figure standing for the conflict-ridden divide between the two Germanys' (Keller 1994, 5), known both for his enduring belief in the Socialist cause and for antagonizing the GDR authorities with challenging plays that were often banned as a result. Throughout Müller’s life, Shakespeare repeatedly provided a source of inspiration and of contestation. Müller was adamant that Shakespeare was especially meaningful and politically vibrant in totalitarian states and declared, following the downfall of the East German regime, that now there were 'no more ideas, only markets. And there is no place for Shakespeare on the stock market' (Müller 1998b, 189).

Shakespeare’s importance in Müller’s totalitarian Germany, however, did not mean that his works were treated with veneration. Rather, for Müller, as for his master Brecht, Shakespeare’s plays were raw material (Vassen 1992, 23). His Hamlet/Machine (1977), the eight-page play in five sections for which he is most famous outside Germany, arose from Müller’s avowed desire 'to destroy Hamlet' so as to put an end to his thirty-year twin obsessions with Shakespeare’s tragedy and German history (Müller 1995, 86). Channelling Antonin Artaud’s call, in 1932, for the production of 'Works of the Elizabethan theater stripped of the lines, retaining only their period machinery, situations, character and plot' (Artaud 1993, 76), Müller wrote in the foreword to Hamlet/Machine: 'I think my strongest impulse is to reduce things down to their skeleton, to tear off their skin and their flesh. Then I’m finished with them' (Müller 1995, 86).

That desire to 'finish with' Shakespeare by reducing his work to its bone structure, for Müller, sits side-by-side with his work as a translator of Shakespeare’s plays. He translated As You Like It in 1967 and later recalled

[trying] to translate the text literally with the fewest alterations possible, even in the syntax. It was kind of like sleeping with Shakespeare. After awhile [sic] I felt as if I were in his body and could feel how he moved.

(Müller 1998b, 183)

Müller detached himself from his source text more confidently in his adaptation of Macbeth in 1971, but returned to a much closer relationship with Shakespeare in his Hamlet-translation of 1977, the year in which he also wrote Hamlet/Machine (Greiner 1989, 91). Müller’s destruction of Shakespeare’s tragedy, this suggests, sits side-by-side with its reproduction. In 'Shakespeare a Difference', Müller explains how his generation’s 'long march through the hells of Enlightenment, through the bloody swamp of the ideologies' has transformed Shakespeare’s Hamlet. A line like Horatio’s 'BUT LOOK THE MORN IN RUSSET MANTLE CLAD / WALKS O’ER THE DEW OF YON HIGH EASTERN HILL', can, as a result, be rendered in German as 'IM ROTEN MANTEL GEHT DER MORGEN DURCH / DEN TAU DER SCHEINT VON SEINEM GANG WIE BLUT' (Müller 1989c, 227) or, translated back into English: 'IN RUSSET MANTLE CLAD THE MORN WALKS O’ER / THE DEW THAT GLISTENS FROM ITS STEPS LIKE BLOOD' (Müller 2001, 119).1 The resulting sense of alienation from Shakespeare’s words that forces the audience to sit up and listen anew to the over-familiar text (whether in the Schlegel–Tieck translation or in English) was central to Müller’s own production of his Hamlet-plays in 1989–90: in a staging that lasted eight hours, he inserted his iconoclastic Hamlet/Machine into the gap between acts four and five of his Hamlet-translation, shaking up his spectators’ tendency to consume as light entertainment the violence of Shakespeare’s play (Weber 2012, 7).

It is this desire to unsettle his audience and to force them to engage in a more active, challenging form of spectatorship that also characterizes Müller’s final translation and adaptation of a Shakespeare play. Anatomie Titus lampoons the machine-like passive spectatorship of bourgeois audiences in its description of how, at the sight of Lavinia’s mutilation, 'MASCHINEN/LACHEN UND FLÜSTERN RASCHELN MIT DEN KLEIDERN / UND KLAPPERN MID DEN HÄNDEN AB UND ZU/GLASAUGENBLICKE LEUCHTEN AUD DEM DUNKEL' ('MACHINES LAUGH AND WHISPER RUSTLE THEIR CLOTHES / AND NOW AND THEN THEY CLAP WITH THEIR HANDS / GLASS EYE STARES LIGHT UP OUT OF THE DARKNESS') (Müller 1989a, 151–52; 2012, 103). Like Brecht, Müller wants his audience to be able to engage actively and critically with his work; unlike Brecht, however, whose Verfremdungseffekte aim at helping the spectator find the distance from which to learn the lessons taught by the play’s clear presentation, Müller seeks to create a theatre in which all senses are overstimulated. His is a 'dramaturgy of “flooding”, which virtually inundates the spectator with an excess of theatrical signs, hardly leaving his audience the time to absorb … all the optical and acoustic stimulants' (Keller 1994, 71; my translation). As a result, audience members are 'charged with the task of manufacturing [the] connections' between the multiple materials Müller’s theatre presents (Barnett 2010, 12); theoretically, at least, Müller wishes to leave his audience free to draw their own conclusions.

Accordingly, Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome Ein Shakespearekommentar, as its full tripartite title already suggests, superimposes layers of texts, images, and history so as to overwhelm the spectator’s senses and sensibilities. If, in Müller’s Hamlet and Hamlet/Machine, the playwright still divided the impulse to translate from the impulse to dissect by writing two separate plays that were to be joined only in the 1989–90 production, in Anatomie Titus, the two impulses unsettlingly coexist in a single play. Müller’s translation of Titus Andronicus is in most places remarkably close to its source. This textual closeness coexists not only with barely perceptible cuts, such as the omission of Marcus’s speeches in Shakespeare’s act five, but also with additions that reinforce the violent excesses of Shakespeare’s text. Thus the text of young Lucius’s letter which Demetrius reads aloud turns out to be a loose translation (including the snake-like wriggling of the cut-off tongue) of Philomela’s mutilation in Ovid. Saturninus, meanwhile, in an odd echo of Aaron’s cannibalism in Edward Ravenscroft’s 1687 Titus adaptation, orders Tamora to eat her baby at the final banquet. Most bizarrely perhaps, Lucius, in his exile in the icy cold of the Goths’ snow-covered steppes, cuts off the Roman messenger’s hand before sending him back to Rome, peeled like an onion and frozen.2 The 'anatomy' of the play’s title, clearly, is not just a metaphor for the desire to kill, dissect, and understand Shakespeare’s text, but also stands for a more literal desire to explore the dismemberment of human bodies.

The text of Titus Andronicus that has thus been 'differed' is furthermore framed by a commentary (the Shakespearekommentar of the title), which intrudes on the action at key moments, as do the three Exkurse (formal digressions) on the subjects of the metropolis, politics, and the detective novel and the awkward insertion of an extract from Gustav Sievers’s 'Exkurs über den Neger' ('Digression about the Negro', Müller 1989a, 188). Additionally, the flow of the translation is interrupted by a set of black-and-white photographs, which connect the action of the play with bloody rituals (three impaled dogs), desert landscapes, and the hardships of twentieth-century warfare. Thus the episode of the amputated and frozen messenger is juxtaposed with a photograph of German Second World War soldiers huddling in the snow on the Russian Front and with a reproduction of a Soviet leaflet urging German soldiers to desertion, giving the pseudo-Shakespearean betrayal and cruelty of the scene a truth value that is bolted onto the reproduction of historical documents.

Shakespeare may be metaphorically obliterated in the processes of translation and adaptation, but as the commentary also makes clear, his 'murder' is also paradoxically the act through which Müller becomes wedded to Shakespeare as their bloods and inks mingle:

DEIN MÖRDER WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE IST MEIN MÖRDER

SEIN MORD IST UNSRE HOCHZEIT WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

MEIN NAME UND DEIN NAME GLÜHN IM BLUT

DAS ER VERGOSSEN HAT MIT UNSRER TINTE

('YOUR MURDERER WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE IS MY

MURDERER HIS MURDER IS [OUR] WEDDING

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE MY NAME AND YOUR NAME GLOW

IN THE BLOOD THAT HE HAS SHED WITH OUR INK')

(Müller 1989a, 153; 2012, 104)

Writing, Müller suggests, is equivalent to bloodshed. The fragmentation of the source text and the collage-like technique which overlays and juxtaposes it with multiple other texts and images destroy Shakespeare at the same time as they give him continued relevance and enable the work to live on: 'DISMEMBER REMEMBER' is Müller’s motto in his postscript on the 'Unity of the Text' (1989a, 225).

As a result of Müller’s insistence on the equivalence of the poet’s pen and the anatomist’s knife, his Anatomie Titus represents Lavinia’s plight as both physical (in that it is staged in all its horror) and artistic and literary, taking place in the 'WALD DER KUNST' ´('FOREST OF ART'). Building on the rhetorical excesses of Shakespeare’s Marcus at the moment of his discovery of his dismembered niece, Müller’s commentary presents Lavinia as a 'DENKMAL' ('MONUMENT') that has been hewn into a 'MEISTERWERK DES JAMMERS' ('HOWLING MASTERPIECE') who, akin to a 'RÖMISCHES TRAUERSPIEL' ('ROMAN TRAGEDY'), is observed by Aaron from the wings of his 'WELTTHEATER' ('WORLD THEATER') (1989a, 155–56; 2012, 106–07). Lavinia’s revenge is therefore aimed more at the books which inscribe the violence she has suffered than at its perpetrators:

VOM VOLLMOND UMGETRIEBEN SPUKT DIE TOCHTER

KÄMPFT IHREN KAMPF GEGEN DAS SCHWARZAUFWEISS

DER LITERATUR ES IST DIE MÖRDERGRUBE

DER VERS IST NOTZUCHT JEDER REIM EIN TOD

FEGT MIT DEN STÜMPFEN VOM REGAL DIE BÜCHER

BRENNENDE KERZEN ZWISCHEN IHREN ZÄHNEN

VON DEM VERWAISTEN ENKEL APPLAUDIERT

VERBRENNT AUF DEM PARKETT DIE BIBLIOTHEK

('… AGITATED BY THE FULL MOON

THE DAUGHTER IS HAUNTED ROME HER HOME

FIGHTS HER FIGHT AGAINST THE BLACK AND WHITE

OF LITERATURE IT IS THE MURDERER’S PIT

THE VERSE IS RAPE AND EVERY RHYME A DEATH

SWEEPS THE BOOKS OFF THE SHELVES WITH HER STUMPS

BURNING CANDLES CLENCHED BETWEEN HER TEETH

APPLAUDED BY THE ORPHANED GRANDSON

BURNS THE LIBRARY ON THE PARQUET FLOOR')

(Müller 1989a, 191; 2012, 140)

The conflagration of the library thus identifies poetry as the cause of her injuries, drawing attention to the obscenity of the rhetorical flourishes with which Shakespeare/Marcus greets her amputation. More problematically, however, Lavinia’s revenge on the library also becomes a pretext for Müller to outdo Shakespeare in his violent excesses, as his Lavinia grotesquely toasts her stumps in the flames (1989a, 191).

As the lines cited above show, Müller’s additions exacerbate the friction between the different layers of his text visually as well as stylistically: the commentary and digressions, printed in capital letters, visually shout their monumental modernity as much as Müller’s unpunctuated, brutal verse or the inclusion of photographs in the playtext. The play is typical of Müller’s combination of violent language and powerful imagery. The interjection of English, as when Müller’s Saturninus speaks of the 'Commonwealth von Rom' in a formulation that makes of Rome a version of the postcolonial British commonwealth (Müller 1989a, 132), or when the play concludes with the trap of the world closing over a final 'HAPPYEND' that transforms the tragedy’s final tableau of mayhem into a kitsch Hollywood romance (Müller 1989a, 223), only works to accentuate the distance between Shakespeare and the present. Müller’s linguistic anachronisms complement the anachronisms of a Titus who displays the beating heart inside his open chest for the benefit of television screens (Müller 1989a, 131). For Müller, the idea of Titus Andronicus as a play about the 'Fall of Rome' prompts an archaeological drive, signalled by the 'SPATENKLIRREN DER ARCHAEOLOGIE' ('GRINDING SPADES OF ARCHAEOLOGY') (1989a, 223; 2012, 167) to excavate and expose the layers of history that separate us from Shakespeare and that, more importantly, connect the Shakespearean past with the traumatic history of the Western world and the global forces that, Anatomie Titus suggests, will bring about its inevitable downfall in the imminent future.

Central to this shift in focus is the attention Müller gives to the role of Aaron.3 In deliberately racist terms that make his commentary an uncomfortable read, Müller both reduces Aaron to the stereotype of 'DER NEGER' ('THE NEGRO') and elevates him to the status of what Vassen describes as 'a collective figure who represents the ecological catastrophe, the economic crisis and the political revolt of the Third World and its revenge for the affliction of the colonizing power hub of the capital by the formerly conquered colonies' (1992, 24–25, my translation). It is Aaron who takes on the roles of plotter, director, and prompter and who, in these roles, orchestrates the Fall of Rome as a black revenge tragedy that will conclude with Rome’s skies darkened with a plague of flies (Müller 1989a, 142, 217). When the commentary pronounces 'DER NEGER SCHREIBT EIN ANDRES ALPHABET / GEDULD DES MESSERS UND GEWALT DER BEILE' ('THE NEGRO WRITES A DIFFERENT ALPHABET / PATIENCE OF THE KNIFE AND POWER OF THE AXE') (Müller 1989a, 156; 2012, 107), it assigns to Aaron the responsibility for scripting Lavinia’s rape and carving her into a work of art. More broadly, it attributes to him the power to rewrite European history and literature with a difference, along the lines of the translation practice Müller had described in 'Shakespeare a Difference'.

Remarkable, in this 'differed' conception of Titus Andronicus, is the way in which Müller uncharacteristically situates his play not in the context of the GDR or Eastern bloc, as had hitherto been his practice, but in a global context. When he first started to work on the play in 1983, he conceived of it as 'a North–South play' whose 'theme is the collision between a European politics and a tropical politics' (Müller cited in Pincombe 2004, 53).4 In the mid-1980s, the economic deprivation of East Germans relative to their Western counterparts was coming to a head and was about to provoke the popular uprising of 1989. Meanwhile, East Germany’s woods were dying because of acid rain and its landscapes were devastated by mining for brown coal (the principal fuel used in the country’s power stations). Air pollution and the deterioration of the national environment were problems of such magnitude that in 1982 the GDR made environmental data a state secret (Wilson and Wilson 2002, 141). For Brecht, speaking about trees had been almost a crime because it involved silence about a multitude of misdeeds ('Was sind das für Zeiten, wo / Ein Gespräch über Bäume fast ein Verbrechen ist / Weil es ein Schweigen über so viele Untaten einschließt!' [Brecht 2003, 70]); by the 1980s the trees themselves had become such a crime scene that it became illegal to speak of them.

Müller’s Anatomie Titus shows awareness of the differential of wealth and the devastation of the landscape, but instead of identifying them as particular to the GDR and/or the 'Second World' of the Eastern bloc, the play displaces his country’s poverty onto Europe’s former colonies. These are imagined, in the text and the illustrations that accompany it, as all-invading, soul-destroying desert landscapes that threaten to overrun the West, with its poisonous landfill sites, machines, and rusting computers (Müller 1989a, 201, 216).5 Müller wilfully elides the differences between Goths, Huns, and Africans, who are bunched together as the oppressed people of the Third World, and between Tamora-the-Goth and Tamora-Empress-of-Rome, whose big-breasted sexual promiscuity makes her into the living embodiment of Rome, the capital of the Western world which breast-feeds its hungry wolves (Müller 1989a, 128; 2012, 80). Müller sees in Aaron’s sexual conquest of Tamora the political conquest of the West by the wild beasts of the African jungle (1989a, 140). Müller’s 'EXKURS ÜBER DEN SCHLAF DER METROPOLEN' imagines the creeping destruction of Europe’s architecture, institutions, culture, and economy by the forces of nature and the chronology-defying invasion of African heroes:

GRAS SPRENGT DEN STEIN DIE WÄNDE TREIBEN BLÜTEN

DIE FUNDAMENTE SCHWITZEN SKLAVENBLUT

RAUBKATZENATEM WEHT IM PARLAMENT…

DIE PANTHER SPRINGEN LAUTLOS DURCH DIE BANKEN …

IM SCHLAMM DER KANALISATION TROMPETEN

DIE TOTEN ELEFANTEN HANNIBALS

DIE SPÄHER ATTILAS GEHN ALS TOURISTEN

DURCH DIE MUSEEN UND BEISSEN IN DEN MARMOR

MESSEN DIE KIRCHEN AUS FÜR PFERDESTÄLLE

UND SCHWEIFEN GIERIG DURCH DEN SUPERMARKT

DEN RAUB DER KOLONIEN DEN ÜBERS JAHR

DIE HUFE IHRER PFERDE KÜSSEN WERDEN

HEIMHOLEND IN DAS NICHTS DIE ERSTE WELT

('GRASS BLASTS THE STONE THE WALLS GROW FLOWERS

THE FOUNDATIONS SWEAT THE BLOOD OF SLAVES

THE BREATH OF WILDCATS WAFTS THROUGH PARLIAMENT …

THE PANTHERS LEAP WITHOUT A SOUND THROUGH THE BANKS …

DOWN IN THE SLUDGE OF THE SEWER SYSTEM

HANNIBAL’S DEAD ELEPHANTS ARE TRUMPETING

THE SCOUTS OF ATTILA WALK DRESSED AS TOURISTS

THROUGH THE MUSEUMS AND THEY BITE THE MARBLE

THEY MEASURE THE CHURCHES FOR THEIR HORSES’

STABLES AND ROAM GREEDY THROUGH THE SUPERMARKET

WITHIN A YEAR THEIR HORSES’ HOOVES

WILL STOMP AND KISS THE COLONIAL LOOT

BRINGING THE FIRST WORLD HOME TO NOTHINGNESS’)

(1989a, 140–41; 2012, 91)

Hijacking the dynamics of Shakespeare’s revenge tragedy to represent the dialectical working of global forces, Müller lends a sense of rightful retribution to his vision of the Third World annihilating the First. Shakespeare’s Titus with its contestation of Rome by the Northern Goths and the African Aaron, then, becomes for Müller the means to imagine a near-future world in which the Cold War has already ended, in which the GDR’s ideological raison d’être of class struggle has become a broader racial conflict, and in which economic and ecological problems can be blamed on the West, which is getting its rightful comeuppance. As he put it: 'I write about more than what I know about. I write in a different time from that in which I live' (cited in Keller 1994, 109; my translation).

By the time Brigitte Maria Mayer decided to repurpose Anatomie Titus for the next generation, the Berlin Wall had been reduced to rubble. The Eastern bloc had ceased to exist as the 'Second World' and reunification had brought about a gradual – albeit slower than hoped for – recovery of the formerly East German economy, a drastic reduction in air pollution, and a concomitant improvement in the natural environment. Müller had died in 1995 after only three years of marriage to Mayer and the birth of their daughter Anna. Müller’s friends, in his last years, were astonished to see how dedicated a father this man who previously had had little time for children had become for little Anna (Hausschild 2001, 461). As the now widowed Mayer continued her work as a photographer and performance artist, brought up their daughter, and travelled to China, India, and Ghana, the confidence of the West was thoroughly shaken by the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001 and the subsequent messy 'War on Terror' in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2007, the 'credit crunch' hit the USA and developed into a global recession, while in the Far East the rise of China as an economic power seemed unstoppable. Meanwhile, in the Middle East, tension was mounting as long-standing dictatorships tried to keep control of militant Islamists and of the increasingly restless unemployed youth who were challenging the status quo.

Ten years after Müller’s death, in Der Tod ist ein Irrtum (The Error of Dying, 2005), Mayer published private photographs of her life with the dramatist alongside studio photographs inspired by the torture of Iraqi prisoners by US soldiers in Abu Ghraib prison. The book represents an important step in Mayer’s mourning process for her husband and was conceived, at least in part, as a way of reminding the now thirteen-year-old Anna (to whom the book is dedicated) of her father and telling her about the love that brought her parents together (Krampitz 2005). The 2006 exhibition of Der Tod ist ein Irrtum included a three-screen high-definition video projected onto a single surface with scenes involving Anna and texts extracted from Müller’s oeuvre. More distanced than the book, the film of Der Tod ist ein Irrtum consists of a montage of Müller’s words and the starkly conceived visuals of bodies they inspire in Mayer.

Anatomie Titus, filmed in 2009, builds on this project and borrows its visual signatures of studio scenes of tightly choreographed movements presented in a three-screen installation format which, at its Berlin première, was accompanied by an exhibition of sketches, set and costume designs, photographs, and texts. Much more clearly than in Der Tod ist ein Irrtum, this installation combines Mayer’s experiences of a world whose axes of economic and political power are in the process of shifting with her intimate response to Müller’s Anatomie Titus, which she anatomizes and reconstructs, dismembers/remembers with the same incisiveness with which Müller had eviscerated Shakespeare’s tragedy. Shakespeare’s words are mostly discarded or translated into contemporary dance, as Mayer focuses her textual attention on Müller’s commentary and digressions. These she extracts and reassembles, in a mixture which also includes some of Müller’s other plays and poems, as film titles, spoken words in Arabic, Chinese, English, or French with German subtitles, and as Müller’s German texts spoken either by a choir in voice-over or by single speakers. She also translates Müller’s metaphors of archaeological excavation, of devastated landscapes, invading sand, and the savage rituals of Rome into literal, starkly beautiful, shots of the archaeological site of Palmyra (Syria), with its classical ruins, the deserts of Egypt and Dubai, and of the ritual slaughtering of a chicken and a dog as a funeral sacrifice in Gambaga (Ghana).6

Presented in the manner of a triptych, the three images of the installation, organized in a deceptively simple margin–centre–margin layout, complement and contradict one another. Mayer and Müller’s shared love of Renaissance art (Mayer 2005, 7) seems to have provided the inspiration for the '(contemporary) baroque' aesthetic of Mayer’s work (Gomes 2012, 73): the set-up of a triptych invokes early modern altar pieces, gold baroque crosses cover the walls of the studio and Lavinia’s dress, and the mannered choreography of the dancers who celebrate the courtly weddings seems inspired by Stuart court masques. Specific scenes are deliberately modelled on Renaissance paintings, such as Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper (Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milano, 1495–98) and Michelangelo’s Resurrection (Royal Collection, Windsor, 1520–25). Miguel Gomes furthermore draws our attention to the installation’s 'statuesque quality of extremely stylised ensembles or individual actors, hardly moving or moving at a very slow pace'. He links these to the 'tableau-like scenes' Shakespeare creates in Titus Andronicus and, beyond that, to the early modern emblems which, like the installation, juxtapose texts and images in a manner that creates a surplus of signification (2012, 74).

If the early modern genres of the triptych, baroque painting, emblems, and the masque were already showing a 'fascination with multiplicity' (Bolter and Grusin 2000, 330), this is brought to a head in Mayer’s installation. Her Anatomie Titus is a prime example of 'hypermedial' art that uses digital technology to bring different media, historical periods, and geographical locations into play, so as to give the viewer access to several simultaneous realities. At times, the severely organized sight-lines of the triptych push the viewer toward a single interpretation; in other tableaux, Mayer juxtaposes elements that have no immediately obvious connection, thrusting the burden of making sense of the multiple signs on the viewer. Mayer thus transforms Müller’s notoriously condensed imagery into visual rhetoric, using the reframing of performers’ bodies, their fragmentation, and their redeployment in different landscapes and studio environments to create dizzying 'rhetorical effects that affect how spectators interpret character and action' (Giesekam 2007, 11). In the process, the Sprachgewalt – the violent language – of Müller’s playtext is married to the Bildgewalt – the violent images – by which Mayer was impressed during her travels to China (Mayer 2009b), creating a powerful hybrid of texts and images. The installation thus creates an overwhelming sensory environment for the viewer, combining a multitude of art forms – film, dance, music, design, architecture – that closely accords with Müller’s own 'dramaturgy of “flooding”' and the collage method he adopted in his plays (Keller 1994, 71, 75).

The complex web of texts, sounds, and images is programmatically set up in Mayer’s 'Prologue', which recalls Müller’s inclusion of historical war photographs in his published play. The sequence is entirely set in a dark pink 'box' studio of sharply delineated perspectives and a modernity suspended in time. As the sound of marching feet grows in volume, in the central screen Lavinia’s white dress becomes a canvas onto which Mayer projects black-and-white archive footage of German soldiers marching toward Stalingrad. The superimposition of images and sound invites the viewer to reflect on the relationship between Titus’s conquest of the Goths and loss of twenty sons in Shakespeare’s play, the massive loss of lives in the Second World War, and an extract from Müller’s Germania 3, a play about the betrayals of Hitler and Stalin. With words that invoke the biblical Last Supper ('YOU HAVE EATEN MY FLESH AND DRUNK MY BLOOD' [Mayer 2009, 00:00:15]), Lavinia bids the dead enter the underworld. On the side panels, meanwhile, female dancers kneel in two V-shaped rows, their palms stretched out in invitation to the viewer to pass between them. The symmetrical arrangement of the screens orients the eye towards the centre of Lavinia’s dress, draws it into her womb/tomb, onto which Mayer now projects archive footage of dead soldiers strewing the ground.

Lavinia’s ability to absorb into her womb the bodies of the fallen is elaborated in the third tableau of the installation, which combines images of Lavinia, with her open crinoline, standing on a pedestal while male dancers crawl into her skirt, framed, on either side, by shots of Cairo’s eerily empty necropolis (Fig. 16.1). The gesture with which Lavinia raises her hands to her breasts is coy; yet those same hands then voluptuously produce red carnations which she strews over the now 'dead' bodies of the men at her feet before declaring: 'DAS GROSSE ROM DIE HURE DER KONZERNE / NIMMT SEINE WÖLFE WIEDER AN DIE BRUST' ('GREAT ROME THE WHORE OF CORPORATIONS TAKES / UP HER WOLVES TO SUCK HER BREASTS AGAIN') (Müller 1989a, 128; 2012, 80). On the one hand, the sequence presents her as a victim of forces beyond her control, as suggested by dizzying rotating camera movements within the strongly patterned studio set and by overwhelming noise on the soundtrack that, at one point, makes her clasp her hands over her ears. On the other hand, it makes of her a voluptuous harbinger of death, as it perversely transforms her coy gesture of self-protection into a sexual invitation that makes of her the whorish representative of Rome’s deadly corporations.

Fig. 16.1 Bild III: 'Die Sieger mit Musik Stopfen die Toten ins Familiengrab' ('While music plays the victors/Gravely gorge their tomb with dead').

Source: screengrab used by permission of Brigitte Maria Mayer.

In the installation, the attack on Lavinia and/as Rome is multiple: only in part does it originate from the throng of two hundred Egyptian men who, on a dusty square, surround her in their contest for the imperial crown,7 and from the rows of Arab soldiers shouting 'Allah Akbar!' ('God is the greatest!') as part of a military drill. Complementing these allusions to an Islamist threat that speak powerfully to Western anxieties following the 2001 terror attacks are scenes filmed in Africa and China. In particular, a pan across the scarred faces of black miners at Ghana’s Obuasi gold mine is accompanied by the installation’s only Shakespearean lines. Aaron’s speech about digging up dead men’s bodies to carve messages into their skin connects digging for gold and facial scarring with the promise of revenge. This African footage is followed by a juxtaposition of different shots of Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, an iconic site that combines historical imperial power (the Forbidden City on the left screen) with present-day political power (the Great Hall of the People on the right screen). The images of the square at night, with cars driving past in the foreground, render banal the memories of the brutal repression of demonstrators on that square in June 1989. Similarly, in the centre panel, Jeanne Moreau’s crone-like Tamora introduces the scene of Lavinia’s rape with a banal description of how the hunt to which Titus has invited the emperor is but 'A BIT OF BLOODSHED IN GOOD COMPANY' (Müller 2012, 87): casual violence is part of civilization. Subsequent images of the Chinese reconstruction of Paris in Tianducheng and of a Chinese factory producing grand pianos suggest China’s ability to absorb, reproduce, and displace the symbols of Western civilization.

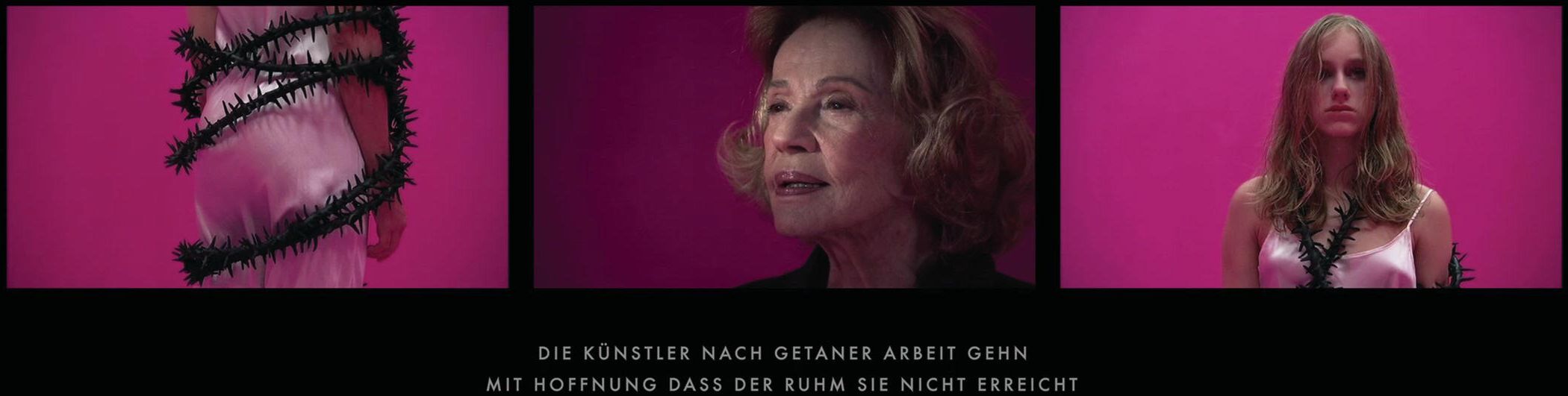

The force of this displacement is made obvious in powerful images of water rushing through the Three Gorges Dam, the symbol of China’s industrial progress and also of its reckless destruction of the natural environment. These images accompany Zhao Jia’s stylized Chinese Saturninus delivering Müller’s digression about the metropolis that ends in the promise that the forces of the former colonies will '[BRING] THE FIRST WORLD HOME TO NOTHINGNESS' (Müller 2012, 91).8 Across the three screens, a cacophony of piano-tuning builds to a crescendo that comes to an abrupt end as all screens show the now dishevelled Lavinia, dressed only in a pink slip that is wound about with a rope of thorns, standing on a pedestal, while Jeanne Moreau’s Tamora, in the centre panel, languorously describes how Lavinia has been transformed into a work of art (Fig. 16.2). In an earlier sequence, her 'rape' was figured through a combination of soundtrack, dance choreography, and the front of Lavinia’s dress suddenly featuring black strings running down to the floor where a black puddle was gathering. Now, the rape is refigured, more through Mayer’s images than Müller’s words, as the rushing forces of environment-destroying industrialization in China and Africa that will appropriate, displace, and engulf European culture.

Fig. 16.2 Bild X: 'Metamorphosen' ('Metamorphoses').

Source: Screengrab used by permission of Brigitte Maria Mayer.

Throughout the installation, the logic of the triptych thus enables Mayer to construct a narrative whose focal point returns time and again to the centre screen even as the side panels pull the eye away into other spaces, periods, narratives. Time and again, the eye is drawn onto the single figure of Lavinia, who most frequently inhabits the focal point of the centre screen and who is played by the now sixteen-year-old Anna Müller. Casting Anna as Lavinia has profound consequences for the installation. Mayer re-centres Müller’s Shakespearekommentar on the figure of the general’s daughter. Under her mother’s direction, Anna Müller’s Lavinia pushes her father’s prophecy of the overthrow of the First World by the Third to the marginal spaces of the side panels by which she is threatened. If Heiner Müller had to dismember Shakespeare so as to remember through him the plot of colonial retaliation, Brigitte Maria Mayer dismembers Müller and Shakespeare in order to remember through them the tragedy of Lavinia, who carries the burden of the past and pays with her blood for the sins of her people. It is her nubile white body, whose soft vulnerability is emphasized by the rigidity of the over-sized dome-shaped crinoline in which she is encased, which is the Western territory that is hotly contested in the dusty squares of the Middle East. In her larger-than-life dress, hers is a larger-than-life screen presence to which, right until the final tableau, it is difficult to attribute individual subjectivity. Instead, Lavinia is presented as a representative, collective, object: a figure onto whom meanings and images can quite literally be projected; a figure whose laboured neutrality of diction, even at the moments of greatest emotional intensity, keeps the viewer at arm’s length.

Anna Müller’s distancing diction sets her apart from the other non-choric characters of the installation. Her Egyptian counterpart Lamia Hamdi lends Lavinia’s prophecy of an escalating civil war magnificent intensity, Erdal Yildiz speaks Titus’s 'anatomy' of his situation with a panting voice that gives expression to his suffering, his African alter ego Chief Gambagarana Wuni pleads in vain for his sons’ lives with weary eloquence, and Jeanne Moreau, with erotic huskiness, savours Tamora’s words of revenge. They all project a subjectivity that steers the viewer towards identifying with their plight. Anna Müller, by contrast, speaks her chiselled verse with an extraordinary lack of expression. More than the words she speaks, either in German or in halting, accented French, it is her diction that identifies her as her father’s daughter, as the true offspring not of Titus, but of Heiner Müller. When directing his plays, Müller was known for asking his actors to speak their lines with studied neutrality that would

uncouple articulation and interpretation in the first instance, subsequently permitting the introduction of gestures which were themselves unnatural. The aim was the presentation of material, be it textual, gestural or proximal, for the benefit of the audience.

(Barnett 2010, 14)

Anna Müller’s performance of Lavinia is true to her father’s ideal, in that her neutral delivery is accompanied by gestures that are rigidly choreographed and intensely artificial, always to be read as presentation of an abstract concept rather than subjectivity. Anna Müller’s Lavinia stands out in her conceptual abstraction.

'Material', the section of her screenplay dedicated to reproductions of inspirational texts and images and of Mayer’s own notes, provides an entry-point into Mayer’s conceptualization of Lavinia. The striking first image is a cut-out, in the shape of Lavinia’s oversized dress, of Eugène Delacroix’s iconic representation of the French Revolution as Liberty Leading the People (Louvre, Paris, 1830). The image bears Mayer’s handwritten inscription 'Lavinia und ihre toten Brüder' ('Lavinia and her dead brothers') and provides a model for the installation’s third tableau, in which male dancers crawl into Lavinia’s skirts. A double-sided photograph a few pages further on shows Anna Müller from behind, the fabric of her dress partially rolled up above the cage of her gigantic crinoline to reveal that she is literally standing on a pedestal. The pages fold up to reveal four sides of sketches of Lavinia in her dress that associate her variously with Stalingrad (as in the finished Prologue), an empty vessel ('Frau = Gefäss'), the Western States/old imperialism/the USA/colonialism, Baghdad, Christ, the crusades, and the catastrophes of the twentieth century. One of the notes reads:

Mode – Weltentwurf – Mädchen

Exaltation der Warenwelt

Kleid + Mädchen

spiegelt

erinnert

verdrängt

sich die Katastrophe

('fashion – creation of the world – girl

exaltation of consumer goods

dress + girl

mirrors

reminds

displaces

the catastrophe')

(Mayer 2009a, n.p.; my translation)

The note links the crinolined body of Anna Müller’s Lavinia on a pedestal – encased in a cage of fashion – to the pages from the Tiqqun collective’s treatise 'Premiers matériaux pour une théorie de la Jeune-Fille' ('Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young Girl'), which Mayer reproduces without further explanation. Tiqqun theorize the teenage girl as the 'model citizen' of 'commodity society'. She embodies the manner in which present-day capitalist consumerism has made 'the most marginalised elements of traditional society – women and the young first, then homosexuals and immigrants' buy into the values it propagates through advertising. 'Youth and Femininity', Tiqqun proclaim, 'will be elevated to the rank of ideals that regulate the integration between the empire and its female citizens. The figure of the Young Girl will thus generate a unity between those two variables that is immediate, spontaneous, and perfectly desirable' (reproduced in Mayer 2009a, 'Materials', n.p.; my translation).

As an abstract representation of Delacroix’s revolutionary Liberty frozen into the shape of twenty-first-century consumer society, Anna Müller’s Lavinia embodies the shell-like quality of the perfectly integrated, fashionably dressed, and emotionally hollow young Western woman who acts as both a mirror and displacement of the catastrophe facing her society. Her groomed hollowness is never more obvious than in the fourth tableau that puts her in the same frame as Jeanne Moreau’s Tamora. While on the side panels, a chicken and a dog are slaughtered in a funeral rite that stands in for Titus’s sacrifice of Alarbus, Tamora’s disgust at how Lavinia can watch the slaughter and lick the blood off her father’s hands highlights the impassiveness of Anna Müller’s figure and voice (1989a, 129). Inspired by a combination of Tiqqun’s treatise and Heiner Müller’s vision of Lavinia as an artwork running along a catwalk, dismembered into a work of art ('DAS KUNSTWERK AUSGESTELLT RENNT HIN UND HER / AUF DEM THEATER LAUFSTEG' [1989a, 151]), Mayer turns the Petrarchan pedestal and fragmentation of the body into the contemporary fashion scene in which the female body is idolized and subjected to a controlling, fragmenting gaze. This is the point of the tenth tableau (Metamorphosen). There, the circling, inquisitive cameras analyse and fragment Lavinia’s body in the side panels as the thorns dig into her flesh and she stands motionless on her pedestal. Her reduction to a work of art is described with connoisseurship by Tamora who, in the centre panel, represents an earlier, mature, unconstrained, and erotic femininity (see Fig. 16.2).

Returning to a preoccupation which first appeared in Der Tod ist ein Irrtum, where Mayer pictured skinny models crawling toward bowls into which they vomited, Mayer furthermore transforms the literally dismembered Lavinia of Shakespeare’s and Müller’s plays into the much more ordinary, yet appallingly widespread, self-starvation of an adolescent girl trying to conform to the unspoken rules set up by Western consumer society. More than the threat of the former colonies, it appears, what threatens Lavinia’s survival are rules of behaviour, dress, and body norms that deprive her of subjectivity as they reduce her to a tortured work of art. While Anna Müller remains unharmed and of normal weight in the installation, Lavinia’s anorexia is suggested by her juxtaposition with the dancers of the Staatsballett Berlin, whose sharply delineated collarbones are accentuated by the severe black bandeau bras that flatten their chests (see Fig. 16.3). As the screenplay’s reproduction of 'Materials' for the installation’s final tableau reveals, a shocking photograph of an anorexic girl acted as the model for the dancers' outfits. The twelve dancers group around the centre-screen Lavinia/Christ-figure in the manner of the disciples in Da Vinci’s fresco of the Last Supper. On the table in front of them, flayed lambs’ heads are lined up to face the viewer. Just prior to this scene, a tableau of cityscapes and deserts devastated by construction work, burning oil wells, and queuing tankers had been accompanied by a voice-over that described Titus as the new Christ who reveals a future in which nature overwhelms Rome’s poisonous landfill sites. At the end of that tableau, the centre panel had morphed the troupe of male dancers crouching on the floor into Michelangelo’s drawing of the Resurrection. In Mayer’s extraordinary final tableau, however, it is not Titus, but Anna Müller’s Lavinia who becomes a rebellious Christ-figure who refuses to atone for the Fall of Rome.

Fig. 16.3 Bild XIV: 'Epilog' ('Epilogue').

Source: screengrab used by permission of Brigitte Maria Mayer.

Unlike the silent heroine of Titus Andronicus and Heiner Müller’s Anatomie Titus, the installation’s Lavinia speaks out against her representation as a sacrificial lamb, protesting against the cultural and religious scripts that demand her death. Directly addressing the camera from her centre-panel position, Anna Müller speaks the final four lines of Heiner Müller’s 'Römerbrief' ('Epistle to the Romans'), a poem which attacks the injustices of Christian beliefs:

ICH HAB DIR VATER ETWAS MITGEBRACHT

IN DEINEN EWIGEN TAG AUS MEINER NACHT

NICHTS WAR NICHTS IST UND NICHTS WIRD JEMALS GUT

SIEHST DU DAS KREUZ ES WARTET AUF DEIN BLUT

('FROM MY ETERNAL NIGHT I’VE BROUGHT AWAY

THIS GIFT O FATHER INTO YOUR ENDLESS DAY

NOUGHT WAS NOR IS NOR EVER SHALL BE GOOD

BEHOLD THE CROSS IT AWAITS YOUR BLOOD')

(Mayer 2009, 00:53:01; Müller 1998a, 'Römerbrief', 57–60)

Using her father’s words against him and dressed, for the first time, in a white robe that does not cut into her flesh, Lavinia lives and speaks with a quiet defiance that contrasts with her previously neutral delivery and signals her rejection of the rigorously constraining regime of God/Titus/Heiner Müller that would forbid her subjectivity. It is the blood of the father, not that of the daughter or, indeed, of Rome (which Müller’s play had imagined nailed to the cross of the South by the invading Goths [1989a, 223]), that is to be spilt to redeem the sins of man.

In Brigitte Maria Mayer’s dismemberment of Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome Ein Shakespearekommentar, Heiner Müller’s and Shakespeare’s texts are remembered with a difference, their plotlines reconfigured into a parable of the orphaned daughter’s survival in a world in which, in accordance with Müller’s prediction, Western consumerism conspires with the economic expansion of Asia, the religious unrest of the Middle East, and the hunger of Africa to demand her Christ-like sacrifice. In the process, Mayer’s installation anatomizes and dismantles the pedestal of suffering onto which Lavinia has been raised by Shakespeare and Müller. The process that is Titus Andronicus reaches a point, in the installation, where the tragedy of Titus and the Fall of Rome become yet another stage in Mayer’s mourning process for her husband and mapping of their daughter’s future. Bach’s final chorale 'Komm, süßer Tod, komm sel’ge Ruh! / Komm führe mich in Friede' ('Come sweet death, come blessed rest! / Come lead me into peace') may, as Gomes suggests, 'no longer [be] as comforting as it may once have been' (2012, 82), but significantly it acts as a sound bridge that connects Lavinia’s refusal of self-sacrifice to the installation’s concluding image of the sun rising on a new day.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Brigitte Maria Mayer for giving me access to her film, to Mike Pincombe for sharing the English version of his article with me, and to Alexa Huang for explaining the Chinese Opera conventions used in Zhao Jia’s performance.

References

- Artaud, Antonin. 1993. The Theatre and Its Double, trans. John Victor Corti. London: John Calder.

- Barnett, David. 2010. '“I Have to Change Myself Instead of Interpreting Myself”: Heiner Müller as Post-Brechtian Director'. Contemporary Theatre Review, 20, 1: 6–20.

- Bogumil, Sieghild. 1990. 'Theoretische und praktische Aspekte der Klassiker-Rezeption auf der zeitgenössischen Bühne: Heiner Müllers Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome Ein Shakespearekommentar'. Forum Modernes Theater, 5, 1: 3–17.

- Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. 2000. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Brecht, Bertolt. 2003. 'An die Nachgeborenen'. In Poetry and Prose, ed. Reinhold Grimm with Caroline Molina Y Vedia, 70–74. New York: Continuum.

- Cassiman, Ann. 2000. '“A Woman is Someone’s Child”: Women and Social and Domestic Space among the Kasena'. In Bonds and Boundaries in Northern Ghana and Southern Burkina Faso, ed. Sten Hagberg and Alexis B. Tengan, 105–31. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Giesekam, Greg. 2007. Staging the Screen: The Use of Film and Video in Theatre. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gomes, Miguel Ramalhete. 2012. '“THE ARTWORK ON EXHIBIT RUNS ABOUT”: Brigitte Maria Mayer’s Filmic Adaptation of Heiner Müller’s Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome'. In Relational Designs in Literature and the Arts: Page and Stage, Canvas and Screen, ed. Rui Carvalho Homem, 71–83. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi.

- Greiner, Bernhard. 1989. 'Explosion einer Erinnerung in einer Abgestorbenen Dramatischen Struktur: Heiner Müller’s Shakespeare Factory'. Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft West: Jahrbuch, 88–112.

- Hausschild, Jan-Christoph. 2001. Heiner Müller oder Das Prinzip Zweifel. Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag.

- Herzinger, Richard. 1995. 'Der Krieg der Steppe gegen die “Hure Rom”: Vitalistische Zivilsationskritik und Revolutionsutopie in Texten Heiner Müllers'. In Heiner Müller – Rückblicke, Perspektiven, ed. Theo Buck and Jean-Marie Valentin, 39–59. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Keller, Andreas. 1994. Drama und Dramaturgie Heiner Müllers zwischen 1956 und 1988, 2nd ed. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Kidnie, Margaret Jane. 2009. Shakespeare and the Problem of Adaptation. London and New York: Routledge.

- Krampitz, Dirk. 2005. 'Love Story im Nachwendeberlin'. Die Welt (13 November). http://www.welt.de/print-wams/article134742/Love-Story-im-Nachwendeberlin.html. Accessed on 5 January 2015.

- Mayer, Brigitte Maria. 2005. Der Tod ist ein Irrtum. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Mayer, Brigitte Maria. 2009a. Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome: A Film by Brigitte Maria Mayer. Berlin: Theater der Zeit.

- Mayer, Brigitte Maria. 2009b. 'Weltbilder – Brigitte Maria Mayer schreibt das Werk von Heiner Müller fort'. Kultur .21. Deutsche Welle – TV. Uploaded on YouTube 18 May 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6yWCtStB_I.

- Müller, Heiner. 1989a. 'Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome Ein Shakespearekommentar'. In Shakespeare Factory 2: 125–226. Berlin: Rotbuch.

- Müller, Heiner. 1989b. 'Hamlet'. In Shakespeare Factory 2: 7–124. Berlin: Rotbuch.

- Müller, Heiner. 1989c. 'Shakespeare eine Differenz'. In Shakespeare Factory 2: 227–30. Berlin: Rotbuch.

- Müller, Heiner. 1995. 'The Hamletmachine'. In Heiner Müller: Theatremachine, trans. and ed. Marc von Henning, 85–94. London: Faber and Faber.

- Müller, Heiner. 1998a. Die Gedichte. Werke 1, ed. Frank Hörnigk. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Müller, Heiner. 1998b. '“Like Sleeping with Shakespeare”. A Conversation with Heiner Müller and Christa and B. K. Tragelehn'. In Redefining Shakespeare: Literary Theory and Theater Practice in the German Democratic Republic, ed. J. Lawrence Guntner and Andrew M. McLean, 183–95. Newark: University of Delaware Press; London: Associated University Presses.

- Müller, Heiner. 2001. 'Shakespeare a Difference: Text of an Address'. In A Heiner Müller Reader: Plays, Poetry, Prose, trans. and ed. Carl Weber, 118–21. Baltimore, MD, and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Müller, Heiner. 2012. 'Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome a Shakespeare Commentary'. In Heiner Müller after Shakespeare, trans. and ed. Carl Weber and Paul David Young, 77–171. New York: PAJ Publications.

- Munkelt, Marga. 1987. 'Titus Andronicus: Metamorphoses of a Text in Production'. In Shakespeare: Text, Language, Criticism, ed. Bernhard Fabian and Kurt Tetzeli von Rosador, 212–34. Hildesheim, Zürich, and New York: Olms-Weidmann.

- Petersohn, Roland. 1990. '“Vorgeformtes verformen”. Überlegungen zu Heiner Müllers Auseinandersetzung mit Shakespeare'. Wissenschaftliche Zeitschift: Friedrich Schiller Universität Jena, 39: 205–08.

- Pincombe, Mike. 2004. '“Titus Our Contemporary”: Some Reflections on Heiner Müller’s Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome'. In Playing Games with Shakespeare: Contemporary Reception of Shakespeare in the Baltic Region, ed. Olga Kubin´ska and Ewa Nawrocka, 50–62. Gdan´sk: Theatrum Gedanense Foundation.

- Vassen, Florian. 1992. 'Das Theater der schwarzen Rache: Grabbes Gothland zwischen Shakespeares Titus Andronicus und Heiner Müllers Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome'. Grabbe-Jahrbuch, 11: 14–30.

- Weber, Carl. 2012. 'A Life-long Discourse with Shakespeare'. In Heiner Müller after Shakespeare, trans. and ed. Carl Weber and Paul David Young, 1–9. New York: PAJ Publications.

- Wilson, Olivia J., and Geoff A. Wilson. 2002. 'East Germany'. In Environmental Problems of East Central Europe, ed. F.W. Carter and David Turnock, 139–56, 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge.