CHAPTER 1

Traditional European Medicine (TEM)

The forest is the house of God,

there his powerful breath

labors in and out.

WILHELM MUELLER, JAEGERS LUST (THE HUNTER’S JOY)

They want medicine from overseas, though better medicine grows in the garden right in front of their houses.

PARACELSUS

Modern mainstream medicine has saved many lives while lessening much suffering. Nevertheless, more and more people are beginning to approach it with skepticism. Despite all of the wondrous chemicals and computer-driven diagnostic techniques, despite the eight to ten percent of Western countries’ gross healthcare system budgets spent on treating asthma, arthritis, diabetes, cancer, and Alzheimer’s, many chronic degenerative diseases are barely affected, not to mention healed (McTaggart 2013, 26; Coleman 2003, 38). Autoimmune disorders are on the rise; children are at risk from the possible damage of vaccines. It is easy to catch an antibiotic-resistant infection in a hospital, and patients become ill or even die from false diagnoses, unsuccessful treatments, or reactions to regularly prescribed medication.

In the United States, where every year around 40,000 people are killed with guns, there is a higher risk of dying at the hands of a physician than of being killed by a firearm. Professor Juergen Froehlich, director of the Department of Clinical Pharmacology at the Medical University of Hannover, Germany, conducted a comprehensive study in German clinics and found that, in the internal medicine department alone, 58,000 patients die from the consequences of unforeseeable side effects from medicines every year. It is commonly believed that all medicinal procedures that are used today have been scientifically tested, for instance, with randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies and elaborate animal tests. But the magazine New Scientist reported that such procedures only take place about twenty percent of the time.

At this point, entire bookcases could be filled with books describing the disastrous situation of our healthcare system.1 Is it, then, any surprise that people seek out alternative, natural methods of healing, which appeal to them as less invasive and less dangerous? Since the 1980s, ancient, venerable, traditional systems from distant cultures, primarily Indian Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), have attracted many seekers, who try out and practice, with more or less success, Reiki healing therapy from Japan, the Huna teachings from Hawaii, healing massages such as Hawaiian Lomi or Japanese shiatsu, Tibetan medicine, Korean medicine, Indian shamanism, Native American shamanism, pranayama, qi-gong, tai chi, and yoga. Small therapeutic sects have also developed that often contradict each other. Meanwhile, the medical establishment responds with scarcely more than a tired smile for such alternative methods, claiming that they might be entertaining pastimes, but when things get serious, evidence-based, scientific, mainstream medicine is the only one true medicine.

Nevertheless, TCM and Indian Ayurvedic medicine prove effective and are based on thousands of years of experience and tradition. However, they come from cultures that are foreign to us in the West, with basic tenets, healing mechanisms, and particular imaginations often quite alien to us. For example, how can we understand what is meant by “liver-blood”? How does one translate “qi”? Or, for instance, what should one of our experts make of a medical text that states the following?

When the common man rouses away the breath of the soul,

that is: there is too much metal for the wood to accommodate.

When the divine envelops the body of the soul with the breath of the soul,

that is: there is too much water for the metal to accommodate.

For the breath of the soul enclosed in the body of the soul

rules those entirely, and makes them wander,

and by wandering the body of the soul flew.

KUAN YIN-TSE OR GUAN JUNZI (IN HEISE 1996, 57)

There are similar questions in regards to Ayurveda, Tibetan folk medicine, and other healing systems. Each medicinal tradition is unique—as are language, religion, and other culturally specific systems of symbols—and has its own personal understanding of the essence of disease and health, their origins and purpose, and the role of the healer and the patient. Each system is closed in on itself, connected within itself, and coherent. Although each has its strong and its weak points, no systems are superior to the others, just as no one can say that there are better and lesser languages. The belief that our model of medicine is universally the best and only way has its roots in our culture—it resembles the assumption that our form of monotheism is the one and only true understanding of God and that there are no other gods; anything else can only be an idol.

In light of this belief, those of European heritage should urgently ask about their own primal medicine. Is there, beyond globalization, beyond international pharmaceutical companies, far removed from complex technology, and independent of today's mainstream medicine, an ancient traditional European lore of healing?

The Assumed Origin of Medicine

In school we learn that so-called Traditional European Medicine (TEM) has its roots in the Middle East. There, about 10,000 years ago, in the region commonly known as the Fertile Crescent, the formerly nomadic, starving hunters and gatherers settled and began to grow grain and domesticate cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats. Freed from the constant pressures of starvation, humans could now turn to intellectual matters. After the seemingly endless, dull Stone Age, during which people lived from hand to mouth, things began to look up for humanity. The first cities in this region were built, their administration became organized, social hierarchies were established, temples were constructed, and writing was invented. Learned priests replaced the primitive shamans ensnared in magic and superstition. The Near East is, as author James A. Michener (1965) said in his mega best seller, The Source, practically the source of all civilization.

Shou-Hsing, the god of long life and medicine, holding a peach

In church, we learn that the Garden of Eden, where the evil snake whispered to Eve, was also found in this region. In this region as well, the “one and only true God” revealed himself, the Chosen People lived, and Jesus was born to the Virgin Mary in order to save the world.

In light of all this, we can expect nothing less than to also find the origin of true healing art here in the eastern Mediterranean. Medical historians tell us about the comprehensive medical knowledge of the Ancient Egyptians, for example, the Ebers Papyrus (15 BCE) with around nine hundred recipes; or the Edwin Smith Papyrus with a detailed understanding of wound treatment; or the clay tablets of the Sumerians and the Babylonians with cuneiform writing that already contained rational, empirical aspects although still bound to magical rituals. Then, medical knowledge moved into Greece, to the holy temple of Asclepius, and with the teachings of Hippocrates (479–365 BCE) a rational, empirical method of healing gained the upper hand. The origins of diseases were now less seen as a curse of the gods, bad magic, the anger of the ancestors, or other such things than linked to natural causes, such as a disturbance in the balance of body fluids (humoral pathology) or environmental influences. This movement made its way to imperial Rome where the physician Galen (130–200 CE) turned it into a comprehensive system of medicine.2 The military physician Dioscorides, a Greek from Asia Minor, wrote the first herbal in the Western world during this time.3

But then came the Migration Period. Starving, boozing barbarian hordes, dense berserkers, with little understanding of the subtleties of civilization, overran the Roman provinces. These were primitive people, still caught up in magical and superstitious ideas. Because they did not consider reading and writing powerful, they had also no understanding of the value of literary tradition; temples and libraries went up in flames. The recorded knowledge of the wise healers and their recipes were in danger of being lost forever. Fortunately, the monks who cared for this treasure trove of wisdom copied the surviving ancient manuscripts and thus secured them throughout the Dark Ages. In addition, they cultivated gardens of trusted medical plants from the Mediterranean region in their cloisters. After many centuries dominated by the superstitions and idol worship of the heathens, the teachings of Galen finally reemerged by way of monastic medicine.

Asclepius with the serpent-entwined staff, which is still the symbol of medicine

During the twelfth century, the original ancient texts—mainly Hippocratic aphorisms and the essays of Galen—which had been lost but preserved in Arabic translations, enriched and expanded medical lore. The interest in Islamic sources led to the founding of independent physicians’ schools in Spain and southern Italy. Not just alchemy, alcohol tinctures, plant and mineral-based pharmaceuticals, however, enhanced the medical arts; more importantly, diagnostic and practical techniques came to the fore, which were based on scholarship, rational thinking, and clear observation of material reality rather than irrational mystical vision. These were all important steps toward the objective, scientific medicine and modern pharmacy that we enjoy today.

Learned physicians at a disputation, from Liber theoricae necnon practicae Alsaharavii, sixteenth century

Traditional European Medicine (TEM), which is ever more popular and often endorsed by natural healers as an alternative to “soulless apparatus medicine,” also fits into this pattern. It, too, relies on Near Eastern, Greek, and Roman origins, on dietetics, on Galen and his complex Galenic mixtures, and on the teachings of the four fluids (humors)—mucus, blood, yellow bile, black bile—which must be balanced out. It, too, relies on the tradition of dutiful monks and nuns who cured their patients in the name of the Lord with herbal wines, salves and tinctures, bloodletting, compresses and enemas, all with the help of Saint Hildegard, Paracelsus (1493–1541), and whoever or whatever else seemed appropriate—until the theory of bacteria appeared in the nineteenth century.4

A Modern Myth

What we read in the books available on the subject of TEM is, from an ethnologist’s point of view, no different from a modern, Western myth. Myths, which are expressions and justifications of the images that a society makes of the world and reality, give meaning and order to that world. “Progress” is an integral part of this Western myth, but not every culture assumes that such a thing exists. For example, for the Australian Aboriginals, the world is as it is, and any change would be a distortion of the primordial dream of the ancestors. The indigenous peoples of Central America see the course of things in a decline and believe that only strict ritual behavior and sacrifice can stem the decrease in universal energy.

A further aspect of this European myth is the uncontested assumption that there is only one correct way of thinking and that it has one single source. The drive to convert others, to missionize, and to let others participate in that truth is part and parcel of that worldview. This attitude contributes to the ideological justification for the colonization of less progressive people. The modern version of this worldview can be seen in the “one world” ideology that serves global business and pushes through so-called universally applicable human rights, the McDonald's-ization of culture, the media conformity dictated by a handful of news and entertainment corporations, and, naturally, the medical system dominated by international pharmaceutical corporations—the only system that might be considered valid.

In the post-Christian era, this “one world” advanced to a secular religion, with its main icon the December 1972 photo from Apollo 17 of the planet Earth floating in the atmosphere like a little blue ball. This “Spaceship Earth,” as the technocratic visionary Buckminster Fuller explained, needs engineers and technologists (key term: global engineering) as maintenance personnel in order to guide and service it (Storl 2004a, 161). The common citizen shivers in awe, but this image of Earth is, in reality, one of absolute alienation. The moist earth that smells of life in which the plants are rooted, the air that we breathe, the wind that blows through our hair, the whispering breezes of the forests, the revitalizing rain, the blossoming meadows, the trusted landscape, and the people who live here with their own culture and customs—all that recedes into the far distance. We often trust television programs more than our actual surroundings, and Facebook friends are “closer” than the neighbors. Would it not be time to come back to direct experience?5 And doesn’t this also hold true—as it concerns our subject—for medicine?

Research in ethnomedicine has certainly established that each ethnicity, each tribe, and each culture has its own complete medical science, just as each has its own language and unique connection to the spiritual dimension of existence. Each indigenous medical system has grown out of the local natural environment and uses the plants and other healing methods that are available in the region. Everyone grapples with disease and infirmity, which are connected to the local climate, the seasons, the lifestyle, and the nutrition of the people who live in the region. As such, diseases have always been just as much a social and cultural product as is the medicine that fights them (Porter 2003, 13). Consequently, each people and its culture has a tradition that develops within its own context and contains many generations of experiences that go back to the time of the forebears.

This is also the case for the native peoples and tribes in forested central Europe, who possessed an effective medical tradition based on experience. It is this primordial, pre-Christian medicine that we want to explore in this book.

The Ecological Embedding of Classical Healing Systems

Healing systems do not exist in vacuums; they are not merely the result of some professor’s abstract theories. Medicine, including that of so-called advanced civilization, is—as far as conceptual models are concerned—embedded in the circumstances of the natural world. The seasons, the latitude and longitude, the local weather and climate, the plants and animals, and the landscape with its mountains, meadows, forests, seas, and rivers not only shape the economic foundation for the society but also influence the conceptual model of the respective medical system (Storl 2010a, 6ff.).

Divine healer Thoth healing the moon-eye of the Sun God, Re

Ancient Egyptian Medicine

Classic Ancient Egyptian medicine would have been inexplicable without the lifeblood of the Nile River, the rising and receding water on the flood plains, the elaborate irrigation system, and the surrounding deserts. According to medical views in the time of the pharaohs, the human microcosm resembled the green Nile Valley. Was human digestion, from mouth to anus, not similar to the life-bringing flow of the great stream? Did blood vessels and veins not resemble the enormous system of canals that regulated and cleaned the water? Did the human pulse not echo the swelling and receding of the river, and were the winds not like human breath? And because the worms and leeches that lived in the canals could make humans sick from infection, it is no wonder that laxatives (castor oil, senna pods, bitter cucumber, figs) or constipating, tannic drugs, vermifuges, enemas, suppositories, diuretics, purgatives, emetics, and bloodletting all played such a significant role in Ancient Egyptian life.

Ayurveda

On the Indian sub-continent, three different seasons provide the basis of Ayurveda, the classical medicine of the Indian high culture:

• the pre-monsoon season with its relentless heat (45 degrees Celsius, 113 degrees Fahrenheit, in the shade);

• the monsoon season with its heavy downpours and high humidity that makes everything moist, slimy, and covered in mildew; and

• autumn and winter with winds and cooler, dryer weather.

Ayurveda describes three conditions (called doshas) that take place in the human microcosm and can be compared to these seasons respectively: Pitta for heat, infections, and inflammation; Kapha for excess fluid and mucous; and Vata for nervous disturbances and anxiety. Medicinal plants and drugs, thus, are prescribed according to the three categories.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

The five phases of transformation—water, wood, fire, earth, and metal—of TCM have their roots in the cycle of the seasons: the winter rain (water) lets the new plants sprout in the spring (wood); these are scorched by the heat of the summer (fire), which can lead to forest fires out of which ash (earth) is created and transformed into the soil; from the earth then come metals, such as copper; and on the metallic surface water condenses, closing the cycle (Ody 2011, 38). Everything is bound together and in constant transformation, not unlike the human system with its seasonal rhythms—wind, cold, dampness, heat, and dryness are not only aspects of the weather or change of seasons and not just external forces affecting health, but they also characterize inner conditions affecting organ functions and moods. For example, water is associated with the kidneys, bladder, and bone marrow: it is cold, its time is midnight and winter, and its taste is salty. Obviously, we are dealing with a complicated, highly sophisticated ideational system. All in all, the duty of medicine is to ensure that this transformation runs harmoniously—not too hastily but also not too hesitantly.

Humoral Pathology

Hippocrates’s and Galen’s teachings of the four humors (called humoral pathology) were based, similar to TCM, on the environment and annual cycles. The warm, moist blood corresponds to the warm, moist springtime of the Mediterranean; the yellow bile, warm and dry, corresponds to summer; black bile to the dry autumn; and mucous to the cold, rainy winter.

The foundation for this classic system of medicine is the vast natural world, the macrocosm. In the human microcosm, the laws work similarly and should be obeyed so that health is assured. Even modern medicine is served by a conceptual model, albeit the machine instead of nature, seasons, and landscapes. During the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, the clock became the model for the motions of the planets as well as the functions of the body. God, the Creator, was depicted as a cosmic watchmaker who constructed the world and wound it up so that it would tick on its own until the end of time. Humans came to be thought of, as far as the body is concerned, as ticking mechanisms. In the nineteenth century, when the steam engine made its victory march, the idea of a driving mechanical energy was added to the model. And at the end of the twentieth century, the model expanded with the introduction of computers; the human mechanism guides the organism to a highly complicated, cybernetic network of mainframe computers: the brain. Our medical spaceship hovers far above, completely cut off from Earth and from nature. Major Tom has it all under control!

European Woodland Culture

Reference to the native-born people of central Europe in this book should be broadly understood. By no means does the term describe the inhabitants of the national states within today’s political borders; the reference is rather to the pre-Christian ethnicities who once settled the vast European forests and worked the land with slash-and-burn agriculture. Mostly, we are talking about the Celts in the west and in the Alps, the Germanic people of the north, the Slavs of the east, and the Baltic people (Latvian, Lithuanian, and Prussian) of northeastern Europe. Even if the languages and individual aspects of any given culture have their differences, these peoples nevertheless have much in common, including their medicine.

These commonalities rest upon these early Europeans’ broad forest ecosystem. The forest was the ecological, economical, and spiritual matrix that shaped their way of life. Their farms and towns were found on small, cleared islands within an immense primordial forest, the European rain forest, which grew abundantly thanks to the rain-drenched Atlantic climate. They built their homes from the wood of the forest; the gift of the trees warmed them in the winter and cooked their food; the ashes fertilized their fields; their swine, cattle, and goats fed on foliage in the summer and acorns and beechnuts from the oaks and beeches in the fall; and the bedding for the stalls, leaves, and dried litter came from the surrounding woods.

Under the trees and in the hedges on the edge of the forest grew vitamin-rich wild fruit—sloe berries, hawthorns, blackberries, barberries, serviceberries, raspberries, blueberries, rowanberries, loquats, sea buckthorn, gooseberries, bearberries, lingonberries, whitebeam berries, elderberries, cornel cherries, crab apples, hazelnuts, beechnuts, and so on—which could be dried and stored for winter use. The most potent medicinal herbs also grew in the ecosystem of the hedge, the transitional zone between the forest and the meadows or fields. Precisely these very plants have played a significant role in ethnology, symbolism, and “superstition” for centuries and continue to today.

In the forest, they also encountered nature spirits who had knowledge of the medicinal plants—clever dwarves, magical animals, elves, and gods. Wise, wild Ruebezahl who lives high in the Giant Mountains is a survivor from this enchanted forest world of distant ancestors. Related to him is the Slavic spirit of the forest, the Leschij, who often appears as a small man, but who can also be as big as a fir tree, or as a bird, bear, tree stump, or plant. The bear and the wolf accompany him, and he can whisper softly or howl like the stormy wind. He is partial to magicians and wise women and sometimes inclined to jest and mislead wanderers or mushroom gatherers. Then, there is Rusalka, who lives by forest ponds or in trees and dances naked by the moonlight in the forest. The solitary wanderer might perhaps meet the ancient Forest Goddess transformed into a witch—Baba Yaga (Storl 2014b). The Baltic people also knew about the green-haired “forest mother” who dresses in green clothes, protects the plants and animals, and punishes misdeeds in the forest such as trespassing on the vert (forest vegetation).

Thus, we see that the trees, the blooming wetlands, the cliffs and rivers, the birds, the fish, and other animals of the forest shaped, more than anything else, the spiritual imagination of the primordial inhabitants, who in part were the ancestors of modern Europeans and their relatives in America.

Mountain Spirit, Ruebezahl (Ludwig Richter, 1848)

Certainly for the Celts, the forest was the embodiment of all that is sacred. Nemetonia is the Forest Goddess of the Gauls, Nemeton the sacred forest, and Drunemeton the oak forest. The Druids, the spiritual leaders of the Celts, were the forest (or tree) wise men (dru = tree; wid = meadow). According to Julius Caesar, the Druid’s education lasted twenty years, a span of time during which they lived “like the deer” in the forest and learned its secrets. Merlin, the archetypal Druid, was depicted as a forest dweller in the company of a bear and a stag. For the Celts, wild animals, such as the stag, bear, wild boar, otter, beaver, rabbit, fox, wolf, and so on, embodied the soul of the forest, or were considered manifestations of the gods. The forest symbolized the world itself, the source, the sacred, the eerie Numinosum.

But these forest people knew neither showy temples nor sacred buildings. Why? The forest itself was their temple. “The Germanic peoples, however, do not consider it consistent with the grandeur of the celestial beings to confine the gods within walls, or to liken them to the form of any human countenance. They consecrate woods and groves, and they apply the names of deities to the abstraction that they see only in spiritual worship” (Tacitus, Germania IX). These are the words the Roman historian Tacitus used to describe the Germanic tribes in the first century, a striking resemblance to descriptions of other forest people. The temples that housed the human-like representation of the gods tend to be later developments and can be traced to the influence of the Romans and later that of the Christians.

The beech tree forest was the sacred place of the central European Germanic people. Here in the forest halls, the wise perceived the murmuring of the gods in the rustling of the leaves; here, for the sake of divination, they carved magical runes into twigs cut from the beech trees and painted them with blood or ochre. The runes were then thrown on a white linen cloth in order to decipher the counsel of the gods.6 The priests also kept sacred horses in these groves, and, as oracles, they interpreted the animals’ snorts and hoof beats. Germanic shamans, dedicated to Odin (or Woden, Wotan), the god of magic, experienced their initiation by hanging upside down from the branch of an ash tree for three whole days, without eating or drinking. The shamans undertook this ordeal to loosen the soul from the body, allowing it to fly into transcendental worlds. Their master, Odin, had first practiced the ritual, after having wounded himself with his own spear, when he hung from the Yggrdrasil ash tree for thrice three days and nights.7 The shamanic god performed this self-sacrifice to acquire the wisdom and power of the runes.

For the Baltic people, the forest served as a gathering place into the nineteenth century, where people brought sacrifices to the gods (Lurker 1991, 811). Still today, important holidays such as summer solstice (also referred to as Midsummer’s Eve and Saint John’s Eve) are celebrated in these sacred groves. The gods reveal themselves in the trees: Perkunas, the lightning-bearing celestial god in the oak, or Laima, the goddess of fate, who dwells in the linden tree. Even the dead temporarily dwell in the trees of the forest—the men mostly in the oaks, the women in the lindens—until it is time for their journey to continue. They may also roam through the forest as birds or animals until they once again inhabit a human body.

For these people, Adam would not have been modeled out of clay and Eve would not have come from the rib of her husband, as the Bible tells us; the first human couple would have come from trees. Thus, for example, the Nordic myths tell how the three primordial gods, Odin, Hoenir, and Loki (also Lodur), walked along the shores of the primordial sea and came upon the trunks of an ash tree and an elm. Odin breathed the breath of life into them, Hoenir gave them emotions, and Loki bestowed the warmth of life and red blood. The dwarves, who are adept at handicrafts, carved the wood and gave them the shape of a man and a woman.

The Roman legions began to press into the forested land north of the Alps about two thousand years ago. For Publius Cornelius Tacitus, it was terra aut silvis horrida aut paludibus foeda—a land covered with horrible forests and dreadful swamps. Although the Mediterranean region was once also covered in hardwood trees, the early urban expansion of civilization—with its intensive clearing for crops, fruit trees, and vineyards, fuel to heat homes, metal forging, and material for the flotillas and bridge making—eradicated the forests. For the Romans, the forest, which the barbarians honored, was a place of fear, dark and foggy as it was, filled with dangerous wild animals and even more dangerous wild people. In order to break the magic, the Roman general Julius Caesar commanded that a sacred grove, a nemeton, near Marseilles be felled. However, none of his legionnaires dared carry out the orders as “the hands of the bravest were shaking” (Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, Pharsalia III, 399–428). When Caesar saw that even the most hardened veterans stood frozen in fear, he took the ax himself, raised it up high, and cleaved into the two-centuries-old oak whose top was lost in the clouds (Brosse 1990, 156).

The Christian missionaries eagerly followed the Romans in their attempts to destroy the mythical world of the forest dwellers; in order to sow the seeds of “the one and only true faith,” they had to vanquish the sacred groves and cult trees. Thus, they let Saint Martin (389–448 CE) fell an ancient spruce tree in Autun, Burgundy, while his student, the Bishop of Angers, had an entire forest, in which the heathens celebrated their “obscene” festivals, burned to the ground. Bishop Amator had a noble spruce, “a blasphemous tree” on which the heads of wild beasts had been hung, chopped down and the stump burned.

The story of the Anglo-Saxon missionary Winfrid (Saint Boniface) is well known, who, under the protection of the armed Frankish soldiers, felled the Donar’s Oak (also called Thor’s Oak) in Geismar, Germany. (Like other majestic oaks, this sacred oak at Geismar was dedicated to Donar, the Anglo-Saxon Thunar or Nordic Thor, the god of thunder and protector of the yeomen. It represented—much like the sacred oak in Uppsala, Sweden, or the Irminsul of the Saxon tribes8—the world tree, the axis mundi, of the Germanic Chatti tribe.) Saint Boniface had a house of prayer built out of this wood and dedicated it to Saint Peter—Peter, as the patron of weather, came to replace the Thunder God Thor (southern Germanic Donar, Anglo-Saxon Thunar), to whom the oak had always been consecrated.

A few years later, Saint Boniface convened the Synod of Liftinae (743 CE). At this church council, it was officially forbidden to worship trees as well as practice other “heathen” customs, such as worshiping sacred stones (menhirs), collecting bundles of herbs, interpreting bird flights, soothsaying, decorating wells, engaging in festive processions to accompany the dead, and so on.9

A monk felling an oak tree (French book illustration, ca. 1220 CE)

Charlemagne also supported the desecration of the sacred heathen forest sites—for instance, the Irminsul of the Saxons that was believed to hold up the heavens—and initiated the clearing of the forest. And the zealous Cistercian monks, in particular, made it their mission to drive all of nature far away, the external wilderness as well as the wilderness in the human soul, and to cultivate what was left. Forest and wilderness belonged to the devil and his unredeemed spirits, the wicked wolves and the bears.

The battle of the new state religion, the religion of the sacrificial lamb, against the forest went on for a very long time—the Christian front pushed into the north against the Vikings and into the east against the Baltic people and the Slavs. The bishops and the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Order, over the course of two hundred years of continual religious wars, repeatedly destroyed the sacred groves and trees of the heathen Prussians, Latvians, and Lithuanians. The heathens practiced retribution by slitting open the stomachs of Christian tree defilers, nailing one end of their intestine to the trunk of a damaged oak, and then forcing them to run around the tree as their viscera unwound. To the missionaries, these actions proved the bloodthirsty hate of the godless; to the pagans, these actions demonstrated their high regard for the sacred trees believed to be inhabited by gods (Mannhardt 1875, 29). The Celts, the Germanic peoples, and the Slavs also practiced this sort of punishment on people who sinned against trees.

The battle against heathenism was simultaneously a fight against the forest and the trees, for the indigenous people gained their strength and spiritual inspiration out of the forest.10

Great Tradition, Little Tradition

The pagans, of whom we are speaking, were illiterate.11 They wrote nothing down, and all that concerns the rest of their culture was nearly completely absorbed by the Romans and the Christians, or obliterated. What could we know about their culture under these conditions? What sources do we have? Archeological excavations and the scripts of Greek and Roman writers, such as Tacitus, Caesar, Pliny the Elder, Strabo, or Marcellus Empiricus, are sparse, and the ones that exist are distorted by the worldview of classical antiquity. No wonder cautious empirical historians are quite skeptical about the information concerning the pagans that comes from these classical sources. On the other hand, they also find the gibberish about “channeled” information and the adventurous fantasies of many esotericists and New Agers even more unhelpful. In light of this dilemma, the following question is reasonable: Can one really know anything about the ancient pre-Christian spirituality of the forest people?

The answer is an unambiguous yes, one can. The key lies in the method of comparative ethnology and folklore studies. For example, when one takes certain elements of folk culture, such as the medicinal use of the elder bush, juniper, or hazel bush in the various regions of Europe, and compares them—and, at the same time, takes into consideration the corresponding fairy tales, customs, and superstitions—a larger picture emerges. This can be further expanded by comparing it with similar customs of other cultures, for instance, the Siberians or the Native Americans of the northeastern forests.

During times of cultural transformation, pillaging, and colonizing through alien invasions, the basic understanding of what the world is about collapses—the Irminsul, the pillar that holds up the heavens, breaks. The ancient gods are dethroned, denigrated, and turned into devils, demons, or servants of the new power. The former power elite, the nobles and priests, are disempowered, killed, or turned to be kept as henchmen of the new rulers.

Nevertheless, even if the gods now had new names and new compulsory laws prevailed, the common people stuck to their ancient ways and methods. The farmers continued to rely on their traditional nature calendars as far as sowing and planting, winnowing, and harvesting were concerned. They still knew the nature spirits, the helpful dwarves, the house kobold, or the forest spirit, and tried to keep them kindly inclined toward the humans with prayers, rituals, and acknowledgement. They still observed the behavior of the wild animals and the flight of the birds and knew how to read their messages. And even today holy “Easter water” (once dedicated to the Spring Goddess Ostera) is still drawn from sacred springs in many parts of Europe. Some housewives still sacrifice a bit of milk, bread, or beer under the elder and know how to get rid of pain, sickness, and other injuries by hanging such ailments ritually in the elder branches. Midwives continued to bring children into the world according to trusted and reliable methods. In the evenings by the fire, grandfathers, grandmothers, or aunts still told the old soul-nourishing fairy tales and stories in which the gods and goddesses transformed into magicians, kings’ children, hunters, and witches, and live on as such. In particular, ancient, trusted methods for healing and medicine continued. People still knew which herb made one sweat, which one was a diuretic, which one healed a fever, which one eased breathing. The herbs continued to be gathered in the manner as they had always been, at the right time, in the morning dew, at the new moon, at the summer solstice, or whenever it is appropriate for that specific herb. One still knew the magic incantations that drew forth their healing power. The old woman, the grandmother, still knew about the different qualities of the nine woods when it comes to the boiling of a medicinal tea. Children still played their traditional games. And one still spoke the language of the ancestors whose wisdom and knowledge remain inherent in the vocabulary and idioms of today.

In contrast to the “high culture”—the upper classes, the powerful—the “lower culture” of the people remained. The American anthropologist Robert Redfield (1897–1957) discussed the Great Tradition and the Little Tradition (Redfield 1953). He proposed a continuum that starts with the pole of urban civilizations based in written culture and ends at the pole of the illiterate, rural folk culture. On the one side, we have politicians, teachers, priests, and bureaucrats, while on the other side, we have the common people who pass on their knowledge orally from generation to generation and who have a direct relationship to the land and the environment.

Historical writing usually comes from the literary culture of the upper classes. This is the case with the history of Western medicine, which traces its path from the Near East through Greece to Rome and through monastic medicine, incorporating the influence of the alchemists and so on. The oral tradition of folk medicine, however, has found therein little notice, instead actual disdain.

Cultural Convergences

Today, we have distanced ourselves so much from the natural foundation of our existence that we hardly realize how much traditional cultures are embedded in the surrounding nature and landscape. The weather, the rhythms of the seasons, the local flora, the soil conditions, and the fauna have deeper influences on the worldview of a people than arbitrary, abstract ideas do.

In central Europe, as discussed, above all, the deciduous forest has influenced the culture since the Mesolithic. Even the first farmers—who appeared about seven thousand years ago in central Europe, slashed and burned the primordial forest in order to clear the fields, and then moved on when the soil lost its fertility—were, in essence, shaped by the forest.

The European forests stretched from the climate-determining Atlantic Ocean in the west far into the north and to the east, where they turned gradually into boreal conifer forests. In the southeast, they were bordered by the Pannonian and west Asian steppes out of which the waves of the Indo-European nomadic shepherds emerged. In the south, they were bordered by the dry Mediterranean. Even if geographical borders cannot be clearly drawn, one can nevertheless confidently speak of a cultural area, cultural complex, or cultural environment of the European forest people just as one can speak ethnologically of the culture complex of the eastern African cattle herders or of the cassava (maniok) growers of the Amazons.12

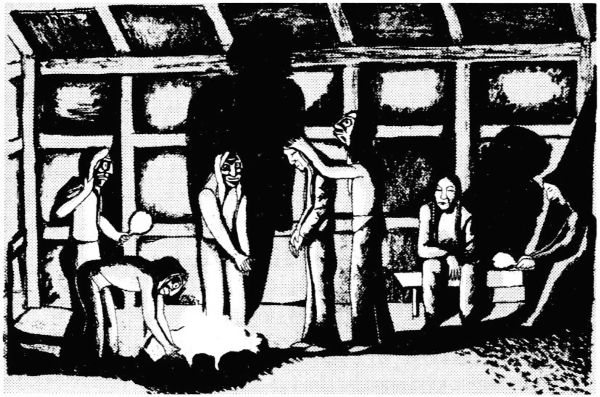

Healing ritual of the Iroquois False Face Society (painting of a Seneca)

European forest culture can also be compared to the woodland culture complex in the eastern deciduous forests of North America. The indigenous people who lived there spoke derivations of the Iroquois or the Algonquin language families and lived in well-constructed longhouses appropriate for the climate and covered with elm bark. Further north, their wigwams were covered with birch bark. These were also slash-and-burn farmers—they grew corn, squash, beans, sunflowers, tobacco, and various greens. The fields belonged to the women, who also cultivated them. The men were responsible for the hunt and protection against possible enemies. These woodland people could be described as matriarchal, just like the European farmers of the Neolithic era and later the Germanic peoples and the Celts, because of their gendered labor division.13 Agriculture was supplemented by hunting and fishing, gathering berries and nuts, and, in the spring, tapping maple trees to make syrup. Like the ancient Europeans, they had a shamanic view of the world, and, as animists, they believed everything in nature had a soul and people could communicate with the natural world.