FREEDOM

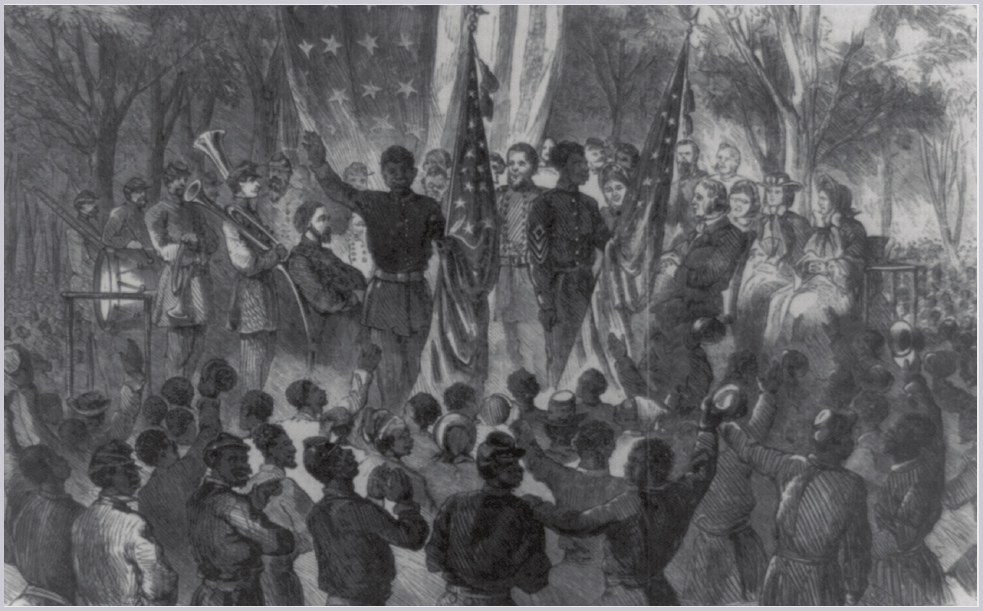

Many people in the North and South celebrated Lincoln’s proclamation. Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson remembered the celebration in Port Royal, South Carolina. “... the President’s Proclamation was read ... Then followed an incident so simple, so touching ... The very moment the speaker had ceased, and just as I ... waved the flag, which now for the first time meant anything to these poor people, there suddenly arose ... singing ... ‘My Country, ‘tis of thee, Sweet land of liberty, Of thee I sing!’”

The Emancipation Proclamation was signed on January 1, 1863, but the Civil War was nowhere near its end. It would take a series of defeats and a shortage of supplies for the Confederates to accept defeat. By the spring of 1865, all the major Confederate armies surrendered. When the Union cavalry captured Confederate President Jefferson Davis on May 10, 1865, the Confederates knew the fight was over.

After the war the Southern states rejoined the Union. Many white Southerners were not happy with their new lives. Eva Jones from Georgia wrote in June 1865, “I suppose you have learned even in the more secluded portions of the country that slavery is entirely abolished ... I know it is only intended for a greater humiliation and loss to us ...”

But former slaves, like Mary Prince, rejoiced. Prince said, “All slaves want to be free—to be free is very sweet ... I have been a slave myself—I know what slaves feel—I can tell by myself what other slaves feel, and by what they have told me. The man that says slaves be quite happy in slavery—that they don’t want to be free—that man is either ignorant or a lying person.”

Printed in Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper on January 24, 1863, “Emancipation Day in South Carolina” depicts the joyous scene Colonel Higginson described.

MAKING IT LAW

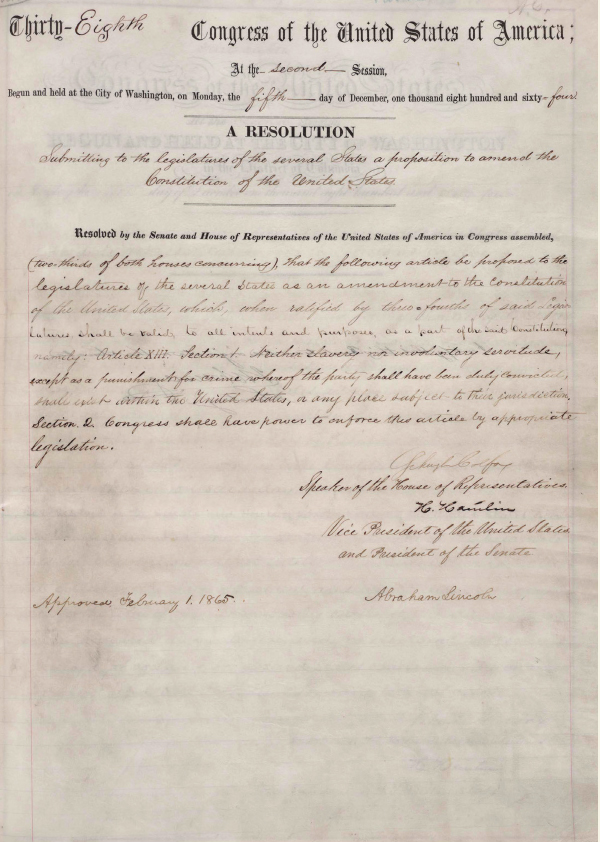

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime ... shall exist within the United States ...”

—13th Amendment

The U.S. Constitution is the law of the land. In January 1865 Congress passed a change to that ruling document—the 13th Amendment. This change would make slavery illegal in the United States. But in order to make the change official, 27 of the 36 states in the Union had to ratify it. Most Northern states approved the change quickly. But Southern states, still angry and rebuilding from the war, were resistant. Finally, in December 1865 enough states had ratified the amendment. Slavery was officially and forever banned from the country.

But that didn’t mean life was instantly better for African-Americans. Freedman Houston Hartsfield Holloway wrote, “For we colored people did not know how to be free and the white people did not know how to have a free colored person about them.” Congress began an era of Reconstruction that lasted from 1866 to 1877. Reconstruction helped blacks and whites learn to live together. Formerly enslaved people began voting, buying land, seeking jobs, going to school, and using public spaces.

This new way of life was a difficult adjustment for black and white people. Many Southern whites, still bitter about the outcome of the war, refused to treat black citizens equally. But African-Americans celebrated their new freedoms.

13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution from 1865

“Now dat’s de way we keeps de ’casion, Happy bright and free,

And we bless good [Master] Lincoln, [Wherever] we may be.

De colored troops fought nobly, dat’s what all de papers say.

And now dey march to vict’ry on Emancipation day.”

—“Emancipation Day” by G.L. Stout and Dave Braham, 1876