Eating and Cooking Thai

Preparing and enjoying an authentic Thai meal

Of the various basic implements used in the preparation of Thai food, a number have remained essentially unchanged over the years. Others have been replaced by more efficient modern devices and are now mainly to be seen in antique shops, objects admired for their beauty of form but not serving a practical purpose for the modern Thai cook.

In a traditional Thai home of the not-very-distant past, the kitchen was nearly always a separate structure from the main house, its central feature being an often smoky stove. Lacking gas or electricity, the fuel was usually charcoal, or wood where it was readily available, as in forested areas like the north. There are still many noted Thai cooks who insist that only charcoal can provide the desired quality of heat for certain dishes and who maintain a small brazier along with the gas and electric cookers that have become standard equipment, at least in city households.

The oldest kind of stove used in Thailand, now virtually extinct, was an ingenious device called a cherng kran. a rimmed earthenware tray with one side raised to hold the bottom of a cooking pot. The fuel was placed under the pot on the tray. This had the advantages of requiring little space and of being easily moved from place. The cherng kran later gave way to somewhat more substantial, but still portable, charcoal cookers and finally to built-in ranges that were made of tiled cement, perhaps reflecting the tendency of the Thais themselves to stay put as more permanent towns and cities developed.

A Few Necessary Implements

The actual cooking of most Thai dishes, past and present, is done with remarkable speed and employs only a small number of utensils, the most important of them being a wok. a spatula with a rounded edge to stir the food around, and assorted pots for boiling.

Different types of spatula for stirring can be used with a wok.

High-tech alloys now replace cast iron as the favorite material for the wok.

Far more time, however, must be spent on the preliminary preparation of various ingredients, which have to be peeled, chopped, grated, ground, blended and marinated, essential procedures that can take several hours for some creations and that led to the evolution of many special tools. One of the most decorative of these was the kude maprow or coconut grater needed to prepare fresh coconut cream or milk This utensil probably began as a simple seat, at one end of which was a sharp iron grater and below this, a tray to receive the shredded coconut meat, all often carved from a single piece of wood. The user straddled the seat and, leaning forward, rotated half a coconut around the teeth of the grater in a process that looked easier than it actually was—the tiniest of slips could result in a painful cut. The kude maprow eventually became more elaborate, with the seat carved in various shapes, usually that of a rabbit (perhaps because of the protruding teeth) but also other animals or humans, and displaying considerable artistry. Today these utensils are comparatively rare and much sought after by collectors However, coconut is today grated by machine in the market or with the use of a food processor at home. To save time, many cooks now rely on packaged or canned coconut cream.

Other classic implements have proved more durable than the coconut grater. The krok and saak, or mortar and pestle, traditionally made of stone or wood but also available in baked clay or metal, is still used to pound and grind spices that produce the distinctive flavors of Thai food. Usually there are two of these, a deep one for up and down pounding and a flat one for grinding.

Traditional coconut scrapers are increasingly rare

Although many traditionally-minded cooks swear that modern blenders and food processers cannot provide the same taste as a mortar and pestle, most cooks even in Thailand today are prepared to trade speed and ease of preparation for the laborious old method. When using a blender to grind items such as shallots, garlic and chilies, be sure to chop or slice all items first, and to blend the tougher ingredients before adding the softer ones Add a little of the cooking medium (oil. coconut milk or water) specified in the recipe, to help keep the blades turning if necessary.

There are, however, no satisfactory substitutes for the thick wooden chopping block and sharp cleaver used in heavy-duty and delicate cutting. These are available in most Asian specialty stores.

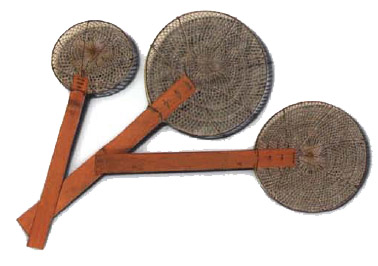

Another important adjunct to the Thai kitchen is a wire-mesh basket with a long handle of wood or bamboo, used to lower foods into oil for deep-frying, to plunge noodles into boiling water and to blanch vegetables. These come in a number of forms, depending on the use— shallow for frying, deeper for holding noodles and vegetables, and are available at every market. (Similar items can be found in Western stores.)

Equally essential for preparing many basic dishes is some sort of steamer Often today this is made of metal and may even be electric, though in provincial areas it is still more likely to be traditional—a set of bamboo trays, for instance, which are stacked over boiling water with a cover on the top one; or, in the north and northeast, an elegant footed utensil known as a kong khao, which can be used for steaming glutinous rice and also for carrying it while traveling or working in the fields.

In addition to these, there are more exotic devices difficult to find outside Thailand, each used for a very specific purpose. One, the ka po. consists of three-quarters of a coconut shell, in the bottom of which are drilled small holes; two parallel rods are attached with rattan to either side of the top so that the shell can be placed on a pot of boiling water. Rice-flour, tapioca, or mung bean paste is poured into the bowl and sieved and served cold. A simpler variation is the lachong, a perforated metal plate that looks like a cheese grater, through which the paste is pressed.

Several brass or bronze implements are also used to make some of the more complex sweets. A cone with two small openings facilitates the production of Foi Thong, or "golden threads," a delicate egg-yolk creation thought to have been introduced by the Portuguese during the Ayutthaya period. A sauce dispenser with a small hole (such as the Kikkoman soy sauce bottle) makes an acceptable substitute, although it takes a fair amount of practice to create these "golden threads."

Another unusual utensil is a shell-shaped mold, usually made of brass, with a long wooden handle. The mold is dipped first into hot oil and then into batter; it is plunged back into the oil and the batter cooks to form delicate crisp little cups. These cups or kralhong are filled to make delightful savory snacks. (Similar snacks known as kuih pi tee are found in neighboring Malaysia and Singapore.)

Some of these implements have now made their way into Western cookery shops specializing in Asian cuisine. While reasonable substitutes can be found for most of the others, the pleasure of a visit to Thailand can be enhanced by plunging into a colorful market and finding the genuine article, which can later be put to practical use.

indispensable wire-mesh baskets used for deep-trying and set of bamboo trays useful for steaming over a wok.

The Thai Dining Experience

Wherever it is eaten—in a restaurant, on a city sidewalk, on the open verandah of a farm house, even in the middle of a rice field at harvest time—a Thai meal is nearly always a social affair. In most urban areas, a table and chairs are likely to be used for dining, though the floor, covered with soft reed mats, suffices in many rural homes. Moreover, Western cutlery has now come into general use: not knives, for in a properly prepared Thai meal nothing is large enough to need cutting, but a large spoon to scoop up individual portions of rice and a fork to help move the food on one's plate.

In the north and northeast, where steamed glutinous rice is preferred, the fingers are used to form small rice balls and dip them into more liquid dishes. Chopsticks may be provided for Chinese-style noodle dishes, and a ceramic Chinese spoon for soups and certain desserts.

A large container of rice is usually the centerpiece, either a wicker basket or an elaborately decorated covered bowl made of silver or pressed aluminium. Around this are placed the other dishes and condiments, and dessert, if one is served. Guests are free to help themselves, mixing dishes at will and seasoning them with a wide variety of condiments to achieve the desired taste. The soup may be eaten at either the beginning or the end of a meal, and the salad likewise. The only constants are the rice, which accompanies almost everything, and dessert, which is usually brought after the other dishes have been removed.

A Feast for All the Senses

The ideal Thai meal aims at being a harmonious blend of the spicy, the sweet and the sour, and is meant to be satisfying to the eyes, nose and palate. Sometimes several of these flavors are subtly blended in a single dish, while sometimes one predominates. In addition to the rice, a typical meal might also include a soup, a curry or two, a salad, a fried and a steamed dish.

There will also be a variety of sauces and condiments: nam pla, the indispensable Thai fish sauce—a salt substitute made from fermented fish, nam prik, which is a spicier version of nam pla mixed with chopped chilies and other ingredients: crushed dried chilies in addition to fresh ones like bird's-eye chilies for those who like their food really hot; pickled garlic; locally made chili sauce, and such fresh vegetables as cucumbers, tomatoes, long beans, water spinach and spring onions.

The most common dessert is one or more of the delectable fruits that are so abundant in Thailand, such as mangoes, jackfruit, lychees, and rambutans. On special occasions, more elaborate desserts may be served, such as Foi Thong ("golden threads"); Sangkaya Fak Thong, a decorative pumpkin custard, and Tab Tim Grob ("red rubies"), water chestnut pieces in a red coating of tapioca flour served in sweet coconut cream and shaved ice.

A late 19th century mural shows the traditional way of eating with the hand while seated on the floor.