“Daladier breathed courage, reflectiveness, and also a certain detachment as if he saw problems from a distance.”

—Jean Daridan, Daladier’s principal assistant

When Hitler or others in Germany made judgments about “France,” they were, for practical purposes, assessing decisions that would percolate through the mind of Édouard Daladier, for, on April 10, 1938, not quite a month after the Anschluss, Daladier became prime minister of France, and he held that office until the spring of 1940.

Daladier’s origins were almost as humble as Hitler’s. Five years older than the German dictator, he had grown up in a village in Provence, in Mediterranean France, where his parents ran a bakery. As Hitler’s mother indulged his desire to go to Vienna to study art, so Daladier’s parents scrimped in order to send him to the University of Lyon. But there any similarity ended, for Daladier proved a hardworking student and successfully completed the training needed to become a professor, specializing in modern French and Italian history.

Daladier’s experience of the Great War had some similarities to Hitler’s. Called up in 1914, he went immediately to the front and remained there throughout. But, having been a reservist before the war, he started off as a sergeant and was eventually commissioned from the ranks. Like Hitler, he was frequently exposed to danger. As a company intelligence officer, he scouted areas in front of the French trenches, was wounded several times, commended often, and given two of France’s highest decorations, the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d’Honneur.

The effects of the Great War on Daladier were very different from those on Hitler. Whereas Hitler’s associations with the war were joyous, Daladier’s were grim. Élisabeth du Réau, author of the best biography of Daladier, cites lines from the field records of a unit with which Daladier served during the second battle of Verdun in 1916:

In darkness, the men had to cover a distance of eleven kilometers, part of which consisted of very muddy roads … obstructed by numerous bodies, German, but mostly French.… The ground was strewn with tree trunks and branches, weapons, clothing, ammunition, grenades, and cartridges. In the paths one had to step over human bodies half buried in the mud. Two men, one a German and the other a French staff officer, were hanging on the branches of a tree.1

Memories such as these would haunt Daladier when he faced the question whether France should go to war again and then, when war was a fact, whether it was to be fought as bloodily as the war of 1914–18.

Daladier, like Hitler, decided after the war to go into politics, but he did so through conventional routes. Before the war, he had been a socialist. Now he affiliated himself with the Radical Socialist Party. Usually simply called Radicals, most members of the party were not socialist at all but centrist, representing rural and middle-class voters united primarily by support for public schools as opposed to Catholic schools, reluctance to pay taxes, and unwillingness to identify clearly with either left or right. Daladier won a seat in the Chamber of Deputies (the French equivalent of the House of Commons or the U.S. House of Representatives). His eventual base was the Provençal town of Orange, where he also served continuously as mayor. Even when wartime prime minister, he would ride by train for ten hours from Paris’s Gare de Lyon down to the south, and spend days dealing with local affairs there and comforting constituents. One French journalist characterized Daladier as “the machine politician par excellence.”2

Within his party and in the Chamber of Deputies, Daladier rapidly rose to leadership. Other young war veterans lined up behind him, and he became the party’s chief spokesman on defense matters. In 1927, he was elected party chairman, temporarily displacing Édouard Herriot, a whale-shaped bon vivant who had been his teacher at Lyon and his first political mentor.

In February 1934, at the age of forty-nine, Daladier briefly became prime minister. He did so at a time of internal crisis in France. He managed badly and almost finished off his political career. The experience affected him perhaps even more profoundly than had that of the Great War.

For France and the rest of the economically developed world, the Wall Street crash of October 1929 had opened what would be remembered as the Great Depression, which at first had little affected France. Large gold reserves and an economy only partially dependent on export earnings had initially provided cushioning. But the reserves eventually ran low, and the beggaring of neighbors had delayed effects. Just as most other developed nations were beginning to recover, France plunged into a slump. From having been the most prosperous country in Europe in the 1920s, France became, along with the United States, the Marxists’ favorite example of the apparent failure of capitalism. National product declined. Prices sagged. The proud French countryside displayed neglected vineyards and fields, with cows and horses so lean that their ribs showed. Rivers running through French cities were lined with jobless workers trolling for fish. The pavements teemed with beggars. France seemed, in the phrase of one economist, to have “a vegetative economy.”3

Largely but not entirely because of the economy, many French people seemed to be losing confidence in their political institutions. The malaise was not so deep as that which had dissolved the Weimar Republic. It resembled more that of the United States in the despairing months before Franklin Roosevelt became president, promising a “New Deal.” But by 1934, many in France were asking whether their Third Republic, created hopefully in the aftermath of the defeat by Prussia in the war of 1870–71, which had celebrated its sixtieth birthday in 1931, would live to celebrate a seventieth.

Most ominous was the possibility of the country’s splitting along ideological lines, maybe even experiencing a civil war. The Communist Party, though still a small minority in Parliament, was noisy and obviously growing stronger. Its umbrella trade-union organization, the CGTU (Confédération Générale du Travail Unitaire), enrolled more than 40 percent of France’s organized workers. Its two national dailies, the morning L’Humanité and evening Ce Soir, were the fourth and fifth most widely sold newspapers in France.4 As in Germany earlier, the radical right was also gaining in numbers and visibility. The streets of Paris saw demonstrations by paramilitary groups menacingly similar to the Blackshirts and Brownshirts of Italy and Germany. The Jeunesses Patriotes affected blue raincoats, the Solidarité Française SA-style jackboots. The largest group, the Croix de Feu, consisted of disciplined, militant war veterans who paraded wearing uniforms and decorations.

The immediate background for Daladier’s short-lived premiership was an incident on which extremists of both left and right seized as a gross symptom of the Third Republic’s corruptness: the arrest in Marseilles of a confidence man named Alexandre Stavisky uncorked a stream of evidence incriminating bribe-takers at all levels of government. Communists and socialists charged a cover-up by the right-wing head of the Paris police, Jean Chiappe. The Jeunesses Patriotes, Solidarité Française, Croix de Feu, and other such bodies immediately came to Chiappe’s defense. Factional leaders in Parliament picked Daladier to be prime minister in the hope that he could mediate.

Daladier failed. When he proposed that Chiappe leave Paris to become governor general of Morocco, Chiappe refused. Moreover, as Daladier heard him, he threatened armed revolt: Daladier said Chiappe had said to him that he would go “à la rue”—take to the streets. Chiappe claimed to have used the phrase “dans la rue,” meaning he would be jobless and out on the street. Whatever the case, contingents of right-wing toughs did go à la rue. They surged through central Paris, apparently intent on attacking the Parliament. Left-wing toughs streamed out to block them. In and around the Place de la Concorde, where the Alexandre III Bridge crosses the Seine to the Parliament and government buildings, demonstrators hurled bricks and bottles and scattered marbles, which caused the horses of mounted policemen to tumble. As night fell, someone fired a gun. No one was ever sure who. Probably, it was some frightened young policeman. Other guns came out. By morning, eighteen were dead and more than fourteen hundred wounded.

Daladier passed the night never quite sure how bad things were or would become. Some of the ministers and deputies milling around him in the Parliament building proposed that he call out the army. Aware of the strength of right-wing sympathy in the regular army, he feared that this would be—or seem—intervention against the left. In the confused, tired wee hours of the morning, some of the young Radicals whom he had included in his cabinet began to urge that they all resign lest their party carry blame for a civil war. Eventually, Daladier accepted their advice. It was a mistake. The police lines held. The commander of the Croix de Feu ordered his veterans not to mix in the fighting. Demonstrators began to disperse. The cabinet that took over from Daladier’s got the credit for the subsequent peace, and he found himself in subsequent days denounced from the right as “murderer” and from the left as “coward.”5

This experience scarred Daladier. After 1940, many would cite the episode as evidence that he had always been weak, indecisive, and inclined to evade responsibility. If he himself had put into words the lessons it seemed to teach, he might have said that it showed the wisdom of being deliberate rather than precipitate, and casting widely for advice instead of listening to just one person or faction. But this may be a way of saying that it encouraged future indecisiveness. Certainly, recollection of February 1934 left Daladier permanently fearful of emotionally charged public demonstrations. Long after the French economy had recovered and public pessimism about the future of France had lessened, Daladier remained hypersensitive about arousing the ire of right-wing extremists.

February 1934 might have marked the end of Daladier’s political career, but it did not. Supporters in Provence remained loyal. As party and parliamentary colleagues looked left and right, they saw few others with Daladier’s capacity for brokering coalitions among the many factions in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Herriot, who had returned as chairman of the Radical party (the Radical Socialist Party), had proved unable to bargain effectively with other party leaders. By 1936, the Radical rank and file had once again chosen Daladier as chairman.

French politics had meanwhile changed in ways that created new opportunities for Radicals. Not long after the 1934 riots, the French Communist Party received new orders from Moscow. Previously, party members had condemned socialists as worse than fascists. Now they were told to speak well of them and to seek an alliance with all parties of the left and even of the center. In parliamentary elections in April–May 1936, the communists increased their strength sixfold. Their seventy-two representatives thereafter made up almost one-eighth of the Chamber of Deputies. The socialists also gained seats. The Socialist Party leader Léon Blum formed a Popular Front government.6 Though communists took no seats in the cabinet, they supported it. So did most Radicals. As one token of Radical support, Daladier entered Blum’s cabinet as minister of war.

From May 1936 until April 1938, when he became prime minister as well as minister of war, Daladier conceived his chief task to be rebuilding and strengthening the French army so that it would not be surpassed by the army that Germany had been in the process of creating even before March 1935, when Hitler declared the Versailles Treaty null and void.

The challenge facing Daladier was partly due to ups and downs in earlier French military policy. During most of the 1920s, France had maintained a much larger army than most people elsewhere in the world thought either necessary or desirable. British and American commentators routinely described France as “militaristic” and “obsessed with security.” In the French Parliament, parties on the left consistently called for cutting military spending. After the Franco-German détente of the mid-1920s, symbolized by the Locarno Pact and its guarantee of the French-German border, some members of center parties began to take a similar position. In 1930, Pierre Cot, a left-wing Radical (who may have been a Soviet secret agent), proposed that the party take as its slogan, “Not another man, not another sou for defense.” Though Daladier did not go quite so far, he came close.7

Meanwhile, the right-center cabinets in power had kept military spending at high levels but had made a dramatic programmatic change. Previously, the army’s chief purpose had been readiness to enforce the peace terms of 1919 in case Germany tried to evade them. After the Locarno Pact, French governments began to invest instead in permanent fortifications designed to protect the frontier in the event that Germany, now apparently tame but clearly growing in power, should again threaten invasion.

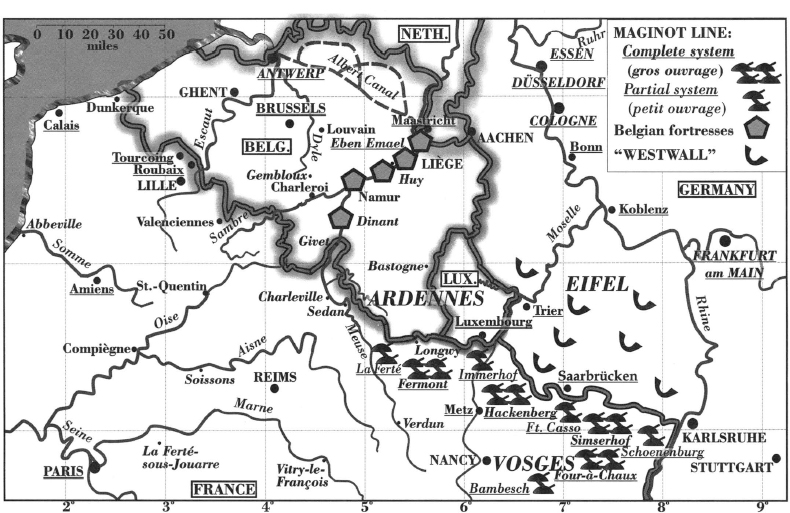

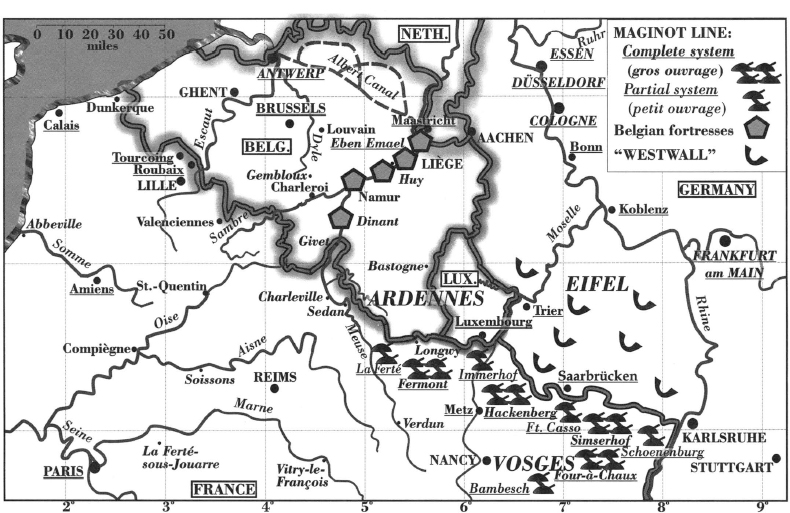

These fortifications were the famous Maginot Line, so called after the then minister of war, André Maginot. Because “Maginot Line” later came to be a synonym for muddle-headed military thinking, a brief digression is needed to defend it both as a concept and as a reality.8 Two of its key premises were beyond dispute: that France could not match Germany in numbers, and that geography made France vulnerable in several wide areas. Even within the smaller boundaries fixed by the Versailles Treaty, Germany’s population was larger by a third. For military purposes, the disparity was particularly great in the “hollow years” between 1934 and 1938, when the numbers of men eligible for army call-up in France would be few because so few potential fathers had been at home between 1914 and 1918. Though the Pyrenees Mountains and the Alps provided natural protection to the southwest and southeast, the Rhine (complemented by the Vosges and Jura ranges) formed a natural barrier in the east, and the Ardennes massif obstructed passage into France from the northeast via Luxembourg and southern Belgium, the whole of Lorraine, from the neighborhood of Strasbourg up to the Ardennes, lay invitingly open.

The logic of the Maginot Line grew directly from these facts. It was designed to compensate both for a comparative shortage of manpower and for geography. Embodying the highest technology of the era, it consisted of carefully sited, heavily armored gun turrets connected by underground rail lines. Elaborate quarters for troops, including kitchens, medical facilities, and vast chambers for storage of ammunition and supplies, were also underground. Well-protected telephone lines permitted men to be summoned in strength to any sector that came under attack. Sheltered aboveground roads permitted rapid transfer of manpower from one chain of turrets to another in case the attack was particularly heavy. One writer likened the Maginot Line to a land-based battle fleet. Leopold Amery (always referred to as Leo), a British Tory member of Parliament who toured the Line in 1939, described it as “the prodigious child of a marriage betweem a cruiser and a mine.”9 Anyone who tours a surviving fragment such as the small chain (petit ouvrage) at Rohrbach, not far from Strasbourg, will see that the Line was a technical marvel of the interwar era, on a par with American or Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile complexes of the Cold War. Because of its design and the strength of each complex, only a small proportion of the troops that France could mobilize needed to be committed to defense of the borders directly opposite Germany.

The Maginot Line and the “Westwall”

The Maginot Line thus did not in itself commit France to a defensive strategy. On the contrary, the existence of the Line made it possible for France, despite its overall inferiority in numbers, to contemplate matching the Germans in a war of maneuver, for only so many troops on either side could mass within the area not covered by fixed defenses—that between the Ardennes massif and the Channel coast. Though some French politicians and even some military men advocated complete commitment to a defensive strategy with construction of fixed fortifications all along the Belgian frontier, what in fact happened was erection there of a very thin defensive line combined with preparation for a war of movement, perhaps in northeastern France but preferably on the Belgian plain.

The building of the Line may have encouraged a tendency among the French people to believe that France could be safe no matter what happened on the other side of the Rhine—a “Maginot Line mentality.” But the illusion was never universal, nor did it last long. The remilitarization of the Rhineland occurred in March 1936. By that spring, when Daladier became war minister, few knowledgeable people in France believed that the Maginot Line did more than ensure that, if the Germans attacked, it would not be through Lorraine. And this was an accurate perception, for the Line always seemed to German military men to be almost impenetrable.

As France began to feel the full effect of the Great Depression, however, overall spending for military forces leveled off and then declined. Because of heavy commitments already made for constructing and outfitting the Maginot Line, even the leveling off meant an absolute decrease in regular spending for the army and navy.

The decrease was all the sharper because in 1928 the French air force had become an independent service and therefore a rival claimant for money. And all three services argued uncompromisingly for priority. Admiral François Darlan, head of the navy, insisted that a 630,000-ton fleet had to take first place. Without it, he said, France could not ensure communications with North Africa and elsewhere or be protected if relations worsened with Great Britain, France’s chief enemy in ages past. Senior air-force officers such as General Jules Armengaud, the service’s inspector general, risked court-martial by publishing pseudonymous articles denouncing the failure of governments and the Parliament to appreciate the need for long-range bombers, the weapons that, in their view, would determine the outcome of any future war. Within the army, Colonel Charles de Gaulle made himself famous by writing a book with a theme anticipating that of Guderian’s Achtung Panzer! It called for relying less on draftees and instead building up elite professional armored forces equipped for rapid offensive operations. (He served his cause badly by coupling the two propositions, for he thus made armored forces a target of attack not only by generals still partial to the horse but by anyone who believed in citizen armies.)10

In these circumstances, governments of the early 1930s resorted to expedients. The period of mandatory service for males reaching age twenty, already cut from eighteen months to one year, was reduced in 1932 to just eleven months. This was followed in 1933 by a 15-percent cut in the officer corps of the regular army. To satisfy both army requirements for air support and air-force enthusiasm for an independent strategic-bombing capability, contracts were let to design aircraft that could serve either as fighters or as bombers. When drawings arrived, the proposed planes seemed likely to do well in neither role. The result was to postpone France’s effort to match the aggressive air-force buildup being advertised by Hitler and Göring.

All these economies affected the efficiency of French fighting forces in the short run, and they would have some effects lingering into 1939–40. Because some of the eleven months of training went simply to getting troops enrolled, tested for aptitudes, and assigned and quartered, and because each recruit was entitled to about a month of furlough, the net effect was to reduce severely the time recruits actually gave to soldiering. And the problem was compounded by economies down the line when scheduled three-week refresher courses and seven-day exercises, supposed to occur periodically over a twenty-eight-year period of eligibility for call-up, either failed to occur or became perfunctory. In 1939, some infantrymen reported for active duty never having fixed a bayonet or handled a grenade. The author-philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre commented on the “respectful terror” he observed in fellow reservists handling weapons they had never seen before.11

Reductions in the officer corps and some accompanying reorganizations meant that practically all regular-army captains, lieutenants, and noncommissioned officers drew duty drilling recruits and hence had little opportunity to exercise regular-army formations, or even to study or practice field maneuvers. This, too, affected performance when the French armed forces were mobilized later.

The short-run effects were probably more important than those in the long run, however, for, after September 1939, the army was to have nine months in which to remedy deficiencies discovered at mobilization, and most commanders—though not all—would put those months to good use. What was most harshly affected was immediate confidence. Career officers in the French army, more than career officers in most other armies, traditionally looked down on draftees and reservists. It was a result of the army’s having remained monarchist after the country became republican and of the officer corps’s being prevented by republican politicians from disciplining civilian soldiers as they wished, and it was a reason why French career officers had such a strong preference for serving in colonies rather than at home. In the 1930s, even the officers and noncommissioned officers least prejudiced against civilians were skeptical of men with only eleven months of training to cope with an emergency, and this in a period when there was much speculation about an emergency at home, and when photographs and films coming out of Germany seemed to show disciplined mass armies in formation and new tanks and other equipment rolling off assembly lines.

Daladier was to claim to have started France’s rearming against the Nazi threat. That was an exaggeration, for his predecessors had already commenced a turnaround. What Daladier did was to intensify the effort and, perhaps most important, to begin to remedy inefficiency and fragmentation. Though most of the socialist bloc within the Popular Front remained dogmatically antimilitary, the communists were now under orders to support, not resist, military spending. Since Daladier could count on backing from most fellow Radicals and from others in the center and right who were traditionally promilitary, he had the parliamentary votes for an ambitious rearmament program.

The highest obstacles were in the cabinet, for Blum and eleven of his twenty ministers were socialists, and several of the Radicals came from the party’s left. (Cot, once the opponent of spending any sou for the military, was air minister.) Yet Daladier succeeded in winning a cabinet vote in August 1936 in favor not only of increased military spending but of a shift to longer-term commitments. Theretofore, defense budgets had run year to year, with service proposals framed in late winter and spring, cabinet action in summer, parliamentary debate in fall, and final authorizations at the beginning of the new year; the Treasury was still able to withhold funds in event of shortfalls in tax revenues or increases in costs of borrowing. Daladier somehow persuaded his colleagues that this was no way for France to try to keep up with Germany, and the cabinet authorized him to put before Parliament a four-year spending program not subject to adjustment by the Treasury.

Within the War Ministry, when Daladier first asked for a four-year program, the army proposed one totaling nine billion francs. He rejected it as too unambitious. The army’s second budget—for twenty billion francs—he pared back. What he won from Blum and the others was approval for spending fourteen billion francs over the four-year-period, approximately one-quarter for tanks and motorized troop transport and 30 percent for new artillery, especially antitank and anti-aircraft guns.12

The nationalization of some armaments factories appeased socialists, who had been willing to arm against Germany but objected to rewarding “merchants of death.” Since manufacturers had never made more than meager profits from chancy, often canceled government contracts, opposition was less than might have been expected. Actual nationalization proved very limited—chiefly small aircraft plants and a few tank factories.13 Combined with multiyear funding, however, even limited consolidation in the defense industry smoothed the stream from service orders to actual deliveries.

Blum meanwhile succeeded in pushing through Parliament some of the domestic legislation that he and his partners had promised. His accomplishments included passage in 1936 of laws limiting the factory workweek to forty hours and guaranteeing industrial workers two weeks a year of paid vacation. After a while the momentum for such reform diminished. To stay in office, Blum had to make increasing concessions to factions and parties of the center-right. In June 1937, he lost a vote in the Senate. Although he did not have to do so, he chose to resign. Camille Chautemps, a Radical, formed a new government with Blum as vice-premier. This held together until January 1938, when Blum and the other socialists all resigned.

Daladier remained in place throughout as war minister. When legislation early in 1938 created a minister of national defense, he took that title as well. This supposedly meant that he would have power to coordinate the three services, but he never tested whether that was so. It was almost if not quite true that, as had been said of an earlier experiment in unifying the French defense establishment, nothing changed except “the headings printed on letters and envelopes.”14 The navy, like navies everywhere, guarded its independence. The air force came under Daladier’s effective budgetary control only because Cot joined the socialists in resigning, and the new air minister, Guy La Chambre, a tall, dark, elegant young Radical senator, characterized by one War Ministry staff officer as “a sort of Hollywood parliamentarian,” regarded himself as Daladier’s disciple.15

Daladier immediately set out to do for the air force what he had done for the army. Though Cot had had authority for multiyear funding, he had not made much use of it, in part because of design problems and in part because of his preoccupation with efforts to nationalize the aircraft industry. Appearing before a combined session of the army, navy, and air-force committees of the Chamber of Deputies in March 1938, Daladier described bluntly the inherited problem. The air staff as well as the minister and his civilian aides, he said, had been far too perfectionist. The Breguet 691, a three-seat fighter-bomber, had been modified more than a hundred times before going into production. Though prototypes of the Amiot 350 and 351 twin-engine bombers had broken world records, that had been a year ago, and planes were not yet coming off the line. The same was true for the Morane-Saulnier 405, a highly maneuverable single-seat fighter, which had been ready for production for two years.16 This confession before the responsible committees of the Parliament proved a prelude to head-cracking in the air force, which would result in a broadening stream of deliveries to operational squadrons.

In March 1938, the air force adopted a plan for a sixfold increase in strength, with its target almost five thousand new planes with speeds above three hundred miles per hour, retractable landing gear, motor-regulated cannon, and other advanced features. After the Anschluss, at the insistence of Daladier and La Chambre, the program was speeded up, calling for all these new planes to be delivered within two years—by the spring of 1940.17

When Daladier became prime minister in April 1938, he kept his posts as war minister and defense minister, and he kept also a preoccupation with building up France’s ground and air forces. His own experience in the Great War made him loath even to think of sending these forces into battle. The trauma of February 1934 had left him deeply cautious about adopting any policy that might arouse violent public dissent. At the same time, he was proud of the military instruments that he had helped to create, and sure that the armament program he had sponsored would have a deterrent effect on Hitler.

Burly and dark-complected, with his shoulders usually hunched, and his balding head pulled toward his chest, Daladier was thought by many to be a tough and somewhat willful leader. He had been nicknamed “the Bull of the Camargue” by journalists in his home region. The reference was to the marshland west of Provence famous as a breeding ground for fighting bulls. Parisian journalists substituted “Bull of the Vaucluse.” Jean Montigny, a deputy from the right wing of the Radical party, commented on Daladier’s “Roman head” and wrote: “He gives an impression of energy, will, and controlled power.”18

Some men who had opportunities to observe Daladier closely thought his apparent forcefulness and resoluteness were masks. Jules Jeanneney, the president of the Senate, concluded that Daladier retreated into taciturnity and gruffness because he was embarrassed by his natural indecisiveness. Cot, reminiscing about dealing with Daladier, said: “One thought he was going to say no; in fact, he began gamely by saying no, after which he said perhaps, and then he ended up by compromising if not by giving in.”19

Jean Daridan, who was Daladier’s principal assistant and probably observed him more closely than anyone else, believed that he was best understood as a man of analytic mind, given pause less by inability to decide than by consciousness of complexities. Daridan wrote:

Of medium height but massive presence, with very blue and penetrating eyes, little hair, a sensual nose, and a wry mouth, Daladier breathed courage, reflectiveness, and also a certain detachment as if he saw problems from a distance. He could make fun of himself, but his irony, when applied to others, could be corrosive. With a pleasant manner and no bombast, he excelled, when interrogating people, at making his interlocutors talk and giving them the impression that he had complete confidence in them. His knowledge, especially of history, was vast, his intelligence lively, and I have never seen anyone approach him in ability to make quick study of a question or to make sense out of a file.20

An American journalist adds to the picture of Daladier as interrogator:

He was tactful in public. In private, however, he was blunt, his endless suspicion of others determining his attitude. Eying that drooping cigarette of his, he often risked losing it when he spat out some comment that put his visitor on the defensive. Rich tales were whispered of how he slouched in his chair, then surprised the unwary with some unexpected thrust. Hunched forward, he searched out the truth.… His voice seemed to struggle for expression, as if strangled by emotions at war within him.21

This was the man whose mind Hitler was trying to read when he assessed France through his press clippings and other sources, and whose choices Weizsäcker presumed to forecast on the basis of reports from German diplomats and attachés and German generals on the basis of their own calculations of French military capabilities.