Introduction

“Knowledge of fish is as ancient as fishing”. These words were written in 1958 by two ichthyological experts, Léon Bertin and Camille Arambourg. In our Mediterranean world, we must give credit to Aristotle the Greek (350 B.C.) for having written “A History of Animals”, in which fish are taken into consideration. In this book, our scholar gives succinct information on lagoon-dwelling fishes, saying:

“A quantity of fishes can be found in the lakes formed by the sea: the Mediterranean bream, the gilthead sea bream, the red mullet and most other coastal fishes” – Book VIII, chapter 15 (Aristotle, 1883).

“Mullets, sea bream and sea bass spawn best where rivers flow into the sea […] the sea bass and the mullet spawn in winter […] there are some mullets that are not the result of copulation: they are born from the silt and sand […] just like eels which are born from larvae, mud and worms” – Book V, chapter 10 (Aristotle, 1883).

The interest in lagoon-dwelling fish faded with the disappearance of this “master”. However, the Hispano-Islamic historian and geographer, Abou Obeïd El Bekri, in his Book of Roads and Kingdoms (1068), reports, on the basis of merchants’ and fishermen’s accounts, that “fish are very abundant” in the Lake of Tunis, and he cites the Mediterranean bream, the gilthead sea bream, the “menkou” (which may be the striped sea bream), the “baconis” (which we take to be the mullet), etc. (Miquel, 2003).

Subsequently, the official geographer of King Roger II of Sicily, Al-Idrîsî, in his great work, The Book of Roger or A Companion Book for He Who Wishes to Travel the World (circa 1154-1157), remains silent on virtually all the Mediterranean lagoons, but in Tunisia, the salt lake, Bizerte, and the freshwater lake, Tinja (Lake Ichkeul), which are connected to each other, caught his attention. The author tells us:

“Lake Bizerte is one of the wonders of the world: 12 species of fish can be found there [which he names] and, during each month of the year, one single species is dominant, not mixing with any other […] Its corresponding species disappears and is replaced by a new one” (Bresc and Nef, 1999).

After a long hiatus, Mediterranean interest in ichthyology reawakened in the 16th Century with two famous scholars, the Italian, Ippolito Salviani, and the Frenchman, Guillaume Rondelet. In 1554, the latter published De piscibus marinis, translated from the Latin in 1558 under the title of L’histoire entière des poissons (A complete history of fishes) (Figure I.1). Primarily inspired by Languedoc, this book is, nevertheless, of more general interest because the author presents 241 fish species from the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, etc. Remarkably, Rondelet devotes a chapter to lagoondwelling fishes: “Des poissons des estangs marins. Des estangs é des poissons d’iceux” [On the fishes of marine lakes. On lakes and the fishes therein]. After that, it was not until the 19th Century that pertinent data relating to ichthyofauna and lagoon fishing on the French coasts were made available with the works of Marion, published between 1886 and 1890, and those of Gourret, between 1896 and 1907.

Figure I.1. G. Rondelet, L’histoire entière des poissons, 1558 (French edition of De piscibus marinis, published in 1554)

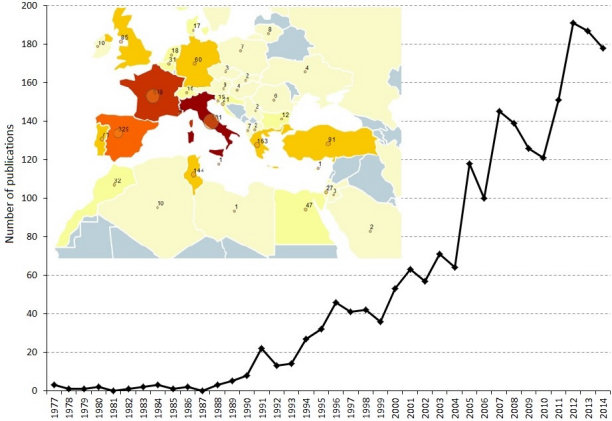

In our times, the bibliographical database Web of Science (Thomson Reuters), discontinued on March 5, 2015, enables us to appreciate the scientific research efforts devoted to the Mediterranean lagoons during the period 1975–2014. More than 2,000 references were inventoried, with a steady growth between 1977 and 2014. Over this time span, three periods can be distinguished (Figure I.2):

- – 1977–1990: a 14-year period with an average of two publications per year;

- – 1991–2004: a 14-year period with an average of 42 publications per year;

- – 2005–2014: a 10-year period with an average of 146 publications per year.

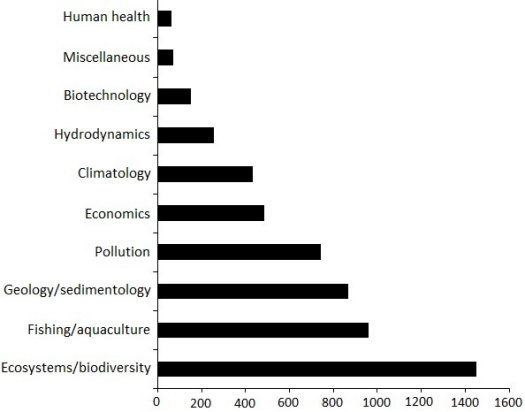

At the source of these works, the Italian and French teams published the most, with 601 and 548 scientific papers, respectively (Figure I.2). They are followed by the Spanish (329), Greek (163) and Tunisian (144) teams. Studies on biodiversity, biology and ecosystems are the most numerous (1,449). Next are the studies relating to aquaculture and fishing (962), geology and sedimentology (869) and pollution (744) (Figure I.3). Studies focusing on economics (487) and climate (433) show a sharp increase in recent years.

Figure I.2. Numerical evolution of publications about Mediterranean lagoons between 1977 and 2014 and their distribution according to country of author. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/kara/fishes1.zip

Figure I.3. Numerical distribution of publications about Mediterranean lagoons between 1977 and 2014 by research topic

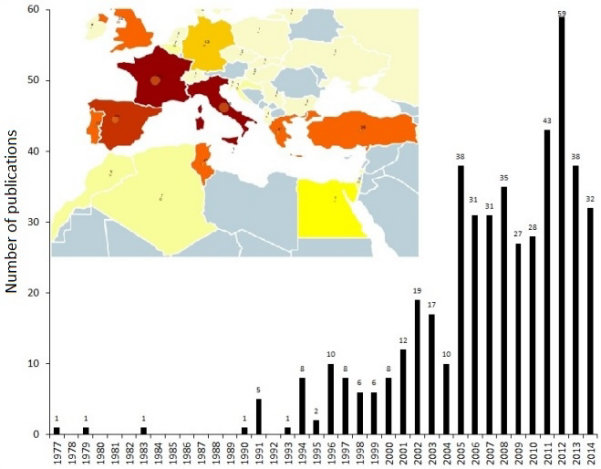

Figure I.4. Temporal evolution (1977–2014) of number of publications on fishes in the Mediterranean lagoons. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/kara/fishes1.zip

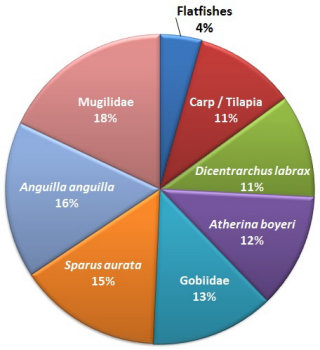

The number of publications devoted to fishes (491) represents 23% of the total number of works devoted to Mediterranean lagoons, and these have been especially numerous over the last decade (Figure I.4). The fishes with which these publications are chiefly concerned are the mullet, eel, gilthead sea bream, gobies, silverside and sea bass (Figure I.5).

Figure I.5. Numerical distribution of publications on fishes of the Mediterranean lagoons between 1977 and 2014 according to species or species groups. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/kara/fishes1.zip

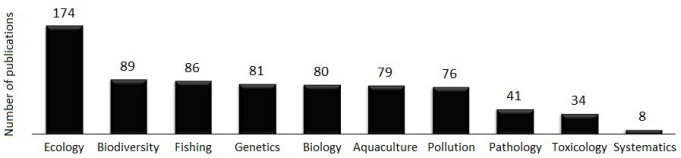

Studies focusing on ecology predominate with 174 publications (Figure I.6). Next are those dealing with biodiversity, fishing, genetics, biology, aquaculture and pollution, with between 89 and 76 publications. Finally, pathology and toxicology have 41 and 34 publications, respectively. The countries whose lagoons are most studied for their fishes are Italy (87 publications), France (69), Tunisia (41), Spain (38), Greece (24), Turkey (23), Egypt (13), Israel (7) and Croatia (7).

Figure I.6. Main topics associated with fishes of the Mediterranean lagoons, according to works published between 1977 and 2014

Despite the wide surface area covered by lagoons, their ecological role and their socioeconomic interest, as well as the existence of an abundance of specialized scientific literature, there have been few syntheses devoted to Mediterranean lagoons and their ichthyofauna. We should mention Kiener (1978) who looks at the ecology, physiology and economics of brackish waters, Kapetsky and Lasserre (1984b) who studied the ecology and exploitation of Mediterranean lagoons, and Cataudella et al. (2015) who compiled information on the interactions between aquaculture, fishing and the environment. Syntheses of a more local nature are available to researchers and managers, such as those devoted to the lagoons in the Gulf of Lion and Corsica (Gourret, 1897; Quignard and Zaouali, 1980 and 1981; Cuenca and Gauthier, 1987; Graille et al., 2000–2001).

The lagoons that are considered here are usually defined as transitional aquatic areas between the continental and marine worlds, connected either permanently or temporarily to the sea. According to the local climate and the relative magnitude of the connection with the catchment basin and the sea, the salinity of lagoon waters varies greatly in space and time. For this reason, these environments host freshwater and marine fauna and flora, lagoon endemism being exceptional (Aphanius iberus, Symphodus cinereus staitii, etc.).

In fact, virtually all the species that live in lagoons and estuaries have representatives in the adjacent fresh and marine waters. Their euryvalence enables them to support the very variable or even extreme conditions in lagoons. Fishes that are able to live and reproduce there permanently are termed “sedentaries” (Pomatochistus microps, Atherina lagunae, etc.); those that live temporarily in lagoons are termed “migrators” (Sparus aurata, Solea solea, Cyprinus carpio, etc.). Of the latter, some undertake regular journeys between lagoon and sea where the adults find favorable spawning conditions (sea-spawning species: Dicentrarchus labrax, Diplodus annularis, etc.); the rest migrate between the lagoon and fresh water where the spawning adults reproduce (river-spawning species: Carassius gibelio, Tinca tinca, etc.).

Finally, certain species make the journey across estuaries (in both directions) in order to reach their spawning grounds in rivers (amphidromous river-spawning species: Alosa fallax, Alosa algeriensis, etc.) or in the sea (amphidromous sea-spawning species: Anguilla anguilla).

Other species, which are relatively numerous, pay random visits to lagoons (Sardinella aurita, Belone belone, etc.). These species are the source of the great biodiversity of 249 inventoried taxa. Thus, fish life in lagoons is, over a limited area, rich and varied and, moreover, in a state of perpetually renewal due to the magnitude of the migration and visitor phenomena.

In this work, we have attempted to inventorize and characterize Mediterranean lagoons from the geographical, morphological and hydroclimatic point of view and then to provide information on the diversity of the fish that live there and also on the main features of their bioecology and exploitation.