5

BUBBLES

Carl Sagan once said that to make an apple pie from scratch you must first invent the universe. He was right. And in inventing the universe you will need to build all the objects and structures that we find in it. These are the planets, stars, white dwarfs, neutron stars, black holes, gas, dust, galaxies, galaxy clusters, and superclusters. Eventually, when this cosmic mix has cooked for long enough, the molecular arrangements will emerge to produce that apple pie. But how does the universe actually build all this stuff? It’s a question for the ages. We have always wondered how our surroundings came to be. Perhaps we’ve sat around our fires and shelters asking one another about the looming silhouette of a great mountain against the twinkling stars, or the brightly lit disk of the Moon. Where did that all come from? For that matter, where and how did we spring out of these monumental forms?

The origin and evolution of objects and structures in the universe is a central and critical question for modern astrophysics, and it is arguably one of the biggest unfinished puzzles in science. In truth, one reason it is not yet complete is because it is a hugely complex problem that stretches both our physics and our imaginations to the limit. We may come up with clean and elegant fundamental rules for how the physics of the universe works, but nature’s application of them is often extraordinarily messy. That is also, of course, part of the fun. For us it’s also a key issue for dealing with the effects that black holes have on the universe, and we really need to get an understanding of the cosmic laboratory in which they are at play. To do this, we can split a big problem into simpler parts to understand it better. In this case, the growth of cosmic objects naturally divides into two large pieces. One is about construction; the other is about preventing that.

Let’s deal with construction first. The glue that the universe builds cosmic structures with is gravity. Gravity springs from Einstein’s mathematical framework for how mass distorts our stiff but flexible spacetime to create its own future paths. The number and variety of objects we see in the universe is in part determined by the effect of gravity on the tiny bumps and kinks of matter that we started out with almost 14 billion years ago. Had the baby universe been perfectly smooth and uniform, it would have remained dull and boring. With no seeds of structure there can be no growth. Exactly how many bumpy and kinky seedlings there were in the very young universe, and where they came from, is part of another fascinating story. For now it’s enough to say that we think we have a pretty good idea of what they looked like. We also feel pretty confident that most of the matter in the universe is dark. This soup of ghostly but massive particles is distinct from the kind of stuff that stars, planets, and human beings are made of. It is the combination of dark and normal matter coalescing and moving around owing to gravity’s glue that provides a very big piece of the building plan for our universe.

We also know that eventually the continuing expansion of spacetime following the Big Bang will put an end to any construction. The immense stretching out of space will isolate material into islands. More and more, matter will end up in small dense objects or dispersed farther and farther apart until nothing new is formed. That, however, is very far in the future.

The second piece to the problem of where all structures and objects come from is a little trickier: it’s all about resistance to building, or even destruction. So is there a yin to the yang of cosmic evolution? Indeed there is. Matter in the universe, rather perversely, also creates many obstacles to its own assembly. The most fundamental hurdle for matter comes from the basic phenomenon of its own pressure, which is in turn related to its temperature. The component atoms or molecules of a material such as a gas are buzzing and bustling around, and we gauge this by talking about how hot or cold the gas is. The hotter the gas and the faster the typical motion of these particles, the greater the particles’ thermal energy. The colder it is, the more sluggish the particles get. Eventually, close to absolute zero, they should all stand still, but for their inherent quantum wiggling and jostling.

What we experience as gas pressure here on Earth is the combination of this thermal motion and the number of atoms or molecules in a particular region. With a ping, ping, ping, the gas particles of our atmosphere bounce against our skin, inside our lungs, and against one another. When you blow up a balloon you are filling it with trillions of air molecules that beat against the rubbery material, causing it to stretch and expand. The thermal motion of the gas creates this property of matter called pressure, which resists efforts to contain it. This is precisely how pressure and temperature work against gravity. Matter will try to fall into, pour into, the deep wells and bowl-like distortions in spacetime caused by mass. But the incessant motion of that matter is like having an infestation of springy fleas that you’re trying to trap inside smaller and smaller boxes. The moving molecules just don’t want to be confined. It’s further complicated because matter tends to get even hotter as it becomes compressed. The same thing happens when you try to pump air into a bicycle tire. The forces of gas pressure resist compression, and some of the energy from your arms is converted into heat, causing the pump to get warm. That heat comes from the speeded-up thermal motion of the gas particles. The hotter the gas gets, the greater the pressure. It is a major obstacle to building objects in the cosmos, yet evidently not an insurmountable one, or you and I would not be here discussing it.

Objects can also explode. Massive stars have a bothersome tendency to end millions of years of nuclear fusion in great cataclysms we call supernovae. Similarly, white dwarfs may be fed just a little too much matter and exceed the critical Chandrasekhar mass, the largest-size object that can be supported by the quantum electron pressure that we encountered before. They implode disastrously. Radiation and particles burst forth to disperse all that carefully gathered material, like an impatient child getting frustrated with a house of cards. And we’ve seen that black holes, small and large, can generate huge outputs of energy with incredible efficiency. All these phenomena act against the gravitational gathering of matter, but despite this our universe clearly reaches a balance. It has to, or else there would either be nothing much present except tenuous gas and dark matter—or all matter would be locked up in black holes. The success of constant construction is clearly tempered by the success of ongoing obstruction; we are surrounded by a shifting and dynamic impasse. And a key discovery that will help us understand this impasse, this point of equilibrium, begins with an extremely famous and rather intimidating family.

* * *

First there was old grandpa Erasmus Darwin, a physician and a highly regarded and historically important natural philosopher in the 1700s. Then, two generations later, along comes Charles. He sails off from England in his twenties for a five-year journey to the exotic southern oceans of Earth. He returns and later helps revolutionize our view of the nature of life. One of his sons, George, makes profound contributions to physics and celestial mechanics. And later one of George’s sons, named Charles in cyclical fashion, becomes a highly respected physicist who helps apply quantum mechanics to the problems of atomic physics in the early twentieth century. Pity the Darwins’ neighbors—personally, I’d focus on making my lawn look better than theirs.

In this brilliant family, it is Charles’s son George Darwin who plays a small but pivotal role in advancing our understanding of how matter in the universe ends up making planets, stars, and even the great clusters of galaxies. It begins with an almost offhand, but deeply insightful, comment by George in the late 1800s. At the time, scientists were working to understand the origins of stellar systems in our own galaxy. A popular theory was the “nebular hypothesis,” which posited that stars and planets formed out of interstellar gas and dust, somehow coalescing and condensing out of this material— although how and why an interstellar cloud, or nebula, would want to do that was a point of uncertainty. While George Darwin’s main scientific efforts went into the complex subject of gravitational tides on planets and moons, he was also very aware that the nebular hypothesis really needed someone to tackle the physics behind it. In a paper published in 1888, he succinctly described what was missing from the theories of the time: the mathematical description of how a rotating cloud of gas could give way to its own gravitational forces to condense into stars and planets. It was a clearly phrased challenge, waiting for someone bold enough to pick it up.

More than a decade passed, and finally, in 1902, a young physicist employed at the University of Cambridge named James Jeans took George’s comment to heart. Consulting with the now-senior Darwin, he dutifully produced a fifty-three-page treatise, “The Stability of a Spherical Nebula.” In this work, Jeans provided the mathematical and physical basis for understanding the fundamentals of what we now call “gravitational collapse.” The essence of it is simple, the practice rather more complex. Jeans established that in a structure like a nebula there are two opposing forces at play. One is gravity. The matter in a nebula has mass, and so it will tend to fall together, shrinking itself. The other force is the natural pressure of the gas. This is the springy force that resists the inward fall of material.

A blob of dense nebula represents more mass than a blob of less-dense nebula, so the greater the density, the greater the gravitational forces at work. But density is also related to gas pressure, temperature, and composition. Jeans saw that high temperature and low density would make it harder for a nebula to condense to make objects like stars. Conversely, low temperatures and high densities would make it easier for gravity to pull material together. Jeans also realized that if you measured just the temperature and density in a nebula, you could immediately calculate the size of a region that would be hovering in balance, just poised to collapse. A smaller region would have insufficient gravity to overcome its gas pressure. A bigger region would have insufficient gas pressure to resist gravity’s embrace. This critical point later became known as the Jeans Mass.

In other words, if you find a nebula that is bigger than its Jeans Mass, then it is almost inevitable that it will be in the process of collapsing and condensing to make stars. Similarly, any cloud of gas that is actively cooling down by emitting radiation stands a good chance of cooling enough that it begins to collapse under its own gravity—especially if its mass is only a little less than the value of the Jeans Mass.

But surely one can just see whether or not a nebula is collapsing, right? Why bother with all this calculation? The problem concerns the human timescale versus the timescales of the cosmos. We’d have to wait around for hundreds of thousands of years to really notice a nebula collapsing to make stars. We’re just too puny and short-lived. Instead we must rely on clues like those we get from Jeans’s equation. He found a way for us to deduce actions of matter that are happening at a snail’s pace from our terrestrial perspective.

We now know that there are many hideous complications to this simple picture. These include the elastic-like effects of interstellar magnetic fields, flowing motions in the nebula, and the endless lumpiness and complexity of material spread around in our galaxy. However, Jeans’s insight is still critical. In a general form it applies across the universe, from the very first generations of stars to those forming in the spectacular Orion nebula in our night sky. Gravity must always overwhelm pressure in order to make objects in the cosmos. It also provides the basis for the next piece of our story, which is all about places not behaving the way you might expect them to.

* * *

Clusters of galaxies might not at first seem to be the likeliest candidates for unveiling the mysteries surrounding the life cycle of black holes in the universe. While a supermassive black hole can occupy a volume similar to that encompassed by the orbit of Neptune, a big cluster of galaxies can occupy a region some 30 million light-years across. The black hole is only 0.00000000001 times the size of the cluster. That’s the size of the period at the end of this sentence compared to one-third of the distance to the Moon. Nonetheless, there is indeed a very special relationship between these two vastly different structures, and it’s one that is connected to the constructive and destructive elements of the cosmos.

I’ve said it before: galaxy clusters are the cathedrals of the universe. These vast systems can contain hundreds, even thousands of galaxies. In this way clusters are the largest “objects” in the cosmos, the great big conglomerations of material at the intersections of the cosmic webbing of matter. As such, they also represent a nearly closed environment, an astrophysical biosphere in which physical phenomena are captured and contained. They are gravitationally bound together within the spacetime distortion of a quadrillion Suns’ worth of mass, composed of dark matter, gas, and stars. As a result, the escape of material is seldom an option.

In these intergalactic biospheres, the majority of normal matter exists in the form of extremely hot and tenuous gas—gas that’s so hot that electrons are stripped from atoms to leave them as ions, the positively charged nuclei and negatively charged electrons coexisting to create plasma. This plasma outweighs all the stars in the galaxy clusters. Most of it is primordial hydrogen and helium, slurped down into the gravity well of the cluster by the same circumstances of imbalance discovered by James Jeans. This deep well is in turn dominated by the unseen dark matter that outweighs all the normal matter in gas and galaxies by about ten times. The captured gas falls ever inward within the gravity well, but as it accelerates it crashes into itself, and converts the energy of this waterfall-like pouring motion into the thermal motion of individual atoms. This is how the gas heats up, and a temperature of 50 million degrees is not unusual inside the biggest galaxy clusters. And the more massive the cluster, the higher the temperature can go.

Hotter gas means higher pressure, and that can stop gravity from compressing the gas any more. Instead it just sits and seethes in the gravitational bucket of the cluster. But over time this gas can also cool off. It can do this by rearranging any electrons that have managed to reattach themselves to ions, squirting out photons of light and releasing that energy. It can also cool as the electrons are decelerated by the electric fields between themselves and the oppositely charged ions of the gas.

This is much like the shrieks of rubber hitting rubber at the bumper-car rink in an amusement park. That noise is energy being lost as the cars whack into their surroundings. Similarly, electrons buffeted about in a plasma emit photons of light to bleed off energy. It’s like the processes of radiation emission seen in particle accelerators that we talked about in the last chapter. The scientific name for the phenomenon is a wonderful mouthful: bremsstrahlung (brems-stra-lung) comes from the German bremsen (to brake) and Strahlung (radiation), and literally means “braking radiation.” Among its many fascinating characteristics, bremsstrahlung from the cooling gas inside galaxy clusters is not visible to the human eye because it’s in the form of X-rays. And, like the bumper cars, the more tightly packed together the electrons are, the more energy they can get rid of—the more rubbery shrieks of X-ray photons—and the faster things cool down.

The first evidence for the existence of this superhot gas in clusters emerged in the late 1960s during the dawn of X-ray astronomy. Unlike the sharp, pinpoint-like X-ray emission of neutron stars and black holes, galaxy clusters are big and cloudy. When you see the X-ray image of gas in a galaxy cluster, you are a direct witness to the amazing dent made in spacetime, filled up with matter like water poured into a bowl. Yet this gas is remarkably tenuous. A cubic meter may contain a total of only a thousand ions and electrons. We only notice it because we see the cumulative light from a depth of millions of light-years into this thin fog. This gas also squeezes in toward the core of a cluster, because of the typical shape of the spacetime bowl. It’s a bit like a soufflé that’s partially successful. All is light and fluffy, except for the embarrassingly thick gummy patch at the bottom. This creates an intriguing conundrum: We know that this bowl of gas cools off by emitting X-ray photons. The primary route by which it does that (the bremsstrahlung) is related directly to how dense the gas is—how many of the electrically charged electrons and ions there are in any given region. If particles are closely packed, the cooling happens faster. So the cluster should be cooling most rapidly at its center, where the gas is densest. But cooler gas means lower pressure, which leads to gravity squashing matter further together, making it even denser and allowing it to cool even faster.

This can act as a runaway process, not unlike a car perched on a hilltop without its emergency brake on. At the top of the hill the slope is gentle, and if I inadvertently lean on the car, it moves just a bit at first. But if I fail to jump in and apply the brakes, then it picks up even more speed, until eventually all I can do is watch in horror as it whizzes down the hill and off an inconveniently located cliff.

Essentially the same thing should happen in a galaxy cluster. The thicker gas in the core cools faster by pumping out more X-ray photons. As it cools its pressure will decrease, and gravity will cause it to slump inward. If the temperature of this gas drops by just a factor of three, it will shrink down inside the gravity well to become twenty times denser. It’s James Jeans’s argument for the collapse of nebula gas all over again: when temperature and density drop below a magic level, gravity takes over. Inside a galaxy cluster, this rapidly cooling gas will begin to roll down the hill, toward the center. But unlike my unfortunate car trundling down a slope, this gas is also supporting lots more gas above it, the rest of the soufflé. Take away that support and the material above will also slump inward. So the outer gas will in turn pour down the bowl sides, increasing in density and cooling more rapidly. It’s as if I had tied my car to the front of a whole chain of other cars, all destined for the cliff edge.

In the outer realms of a galaxy cluster the gas cools at a very slow rate. In the center, though, the runaway process can cool down hundreds of times the mass of the Sun in gas every year. That may not sound like much, but a typical cluster has been around for billions of years, so that adds up to an awful lot of material turning into a thick cold nebula. And thick cold nebulae, as James Jeans saw, have a tendency to collapse further, condensing into stars.

This characteristic of galaxy clusters began to emerge into scientific discussions in the mid-1970s. By this time, early generations of orbiting telescopes had found intriguing signs of dense and bright X-ray emitting gas in the very centers of a couple of these huge systems. One of the scientists trying to understand these measurements was Andrew Fabian. The English-born Fabian was one of a new breed of astronomer, cutting his teeth as a doctoral student with rocket-borne X-ray detection experiments. Launched from Australia and Sardinia, the rockets gave him ten-minute-long peeks above Earth’s atmosphere and into the cosmos. Continuing his postdoctoral career at the University of Cambridge—still his scientific home today—Fabian, together with his student Paul Nulsen, joined a few other scientists around the world in eagerly studying the physics behind the intriguing new images of galaxy clusters. At the center of some, the density of the gas and its X-ray emission indicated it was cooling down in less than 10 million years, the blink of a cosmic eye. The investigators quickly realized that this could be precisely the signature of a runaway process, and this great cosmic downfall of gas soon earned the name “cooling flow.”

Most large galaxy clusters also have a big galaxy sitting in their centers. These central objects are of the elliptical class, each a dense dandelion-like cloud of hundreds of billions of stars. All that cooling cluster gas should end up in these central objects. It could even be responsible for building these galaxies in the first place, and they should still be rife with the formation of new stars. But there’s a catch: something is amiss. Nature is not playing ball. Gas cools in clusters, all right, but most of it never actually gets to the point of making stars—a huge problem for what scientists thought was an obvious process.

By the early 1990s, X-ray observations were sophisticated enough to allow for more precise estimates of just what was going on in the centers of the clusters. In most of these systems, the central concentration of X-ray light appeared to match up with the theoretical predictions for “cooling flows.” In some cases the X-ray data was good enough to allow astronomers to estimate the gas temperature itself, which indeed seemed to be dropping in cluster cores. Many scientists staunchly advocated that cooling flows were vital parts of galaxy clusters. They had good reason to. Everything seemed to fit together—or at least almost everything.

The biggest stumbling block was the sheer amount of material that was thought to be cooling down until it no longer emitted X-rays. If it was turning into cool nebula-like clouds these should in turn be condensing into new stars, lots and lots of them. But there wasn’t much evidence to support this. The giant galaxies at the centers of clusters simply didn’t contain a huge excess of young stars. Where cooler gas could be seen, there was very little compared to expectations. In 1994, Fabian tried to come up with a number of explanations for what was going on. It was conceivable that whatever the cooling gas was turning into was simply dark, and effectively invisible. It could be dust, or small and tepid stars. Some gas could be dropping into near invisibility as cold molecules of simple compounds like carbon monoxide. It was also possible that more complex physics was controlling the gas and hiding it. Magnetic fields might be channeling and constraining the gas, and perhaps hot and cold gases were coexisting in complicated structures that fooled our telescopes.

As with so many puzzles in science, new observations and new data would make all the difference. In 1999, and within five months of each other, two mammoth telescopes launched into orbit around the Earth, and they would prove to transform our view of the universe. One was NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, and the other was the Newton Observatory of the European Space Agency’s X-ray Multi-Mirror Mission (or XMM-Newton). Both were designed to collect more X-ray light from astrophysical objects than ever before, and to make the most detailed images and spectra of that light. With this new precision, scientists could now monitor the X-rays from galaxy clusters well enough to closely track the behavior of the cooling gas by exploiting another of its unique characteristics.

In among the hydrogen and helium of this gas are the same kinds of elemental pollutants that we find everywhere in the universe. Produced by generation upon generation of stars and wafted, blasted, and blown out of individual galaxies and protogalaxies, these heavier elements permeate the denser regions of the cosmic webbing. Some of them are particularly visible in X-ray light from hot gas. Iron, for example, has a complex energy hierarchy for the electrons held around its atomic nucleus. Oxygen, the most abundant element in the universe heavier than helium, has similar properties. In these cases, even at temperatures of millions of degrees electrons can stay engaged with their individual atoms, and energetic X-ray photons are absorbed and released at very specific wavelengths or “colors.” The highly advanced instruments on board Chandra and XMM-Newton could sniff out the X-ray photons from these heavy elements. This light provides a unique fingerprint directly related to the gas temperature. It’s like having a thermometer inside a galaxy cluster, and astronomers were quick to put these tools into action, swinging the great observatories to gather up light from the brightest systems in our nearby universe.

Here was the gas, cooling. Down and down it went. And then … nothing. You can imagine the scientists’ consternation. Suspecting a mistake, they quickly reanalyzed the data. But there was no mistake. In cluster after cluster, the gas cooled down as expected, and then, just as it reached a temperature of a little more than 10 million degrees, it stopped. Not only did it stop, it didn’t even accumulate at that minimum temperature—there was no vast snowdrift of piling-up material. You might expect a great mass of this gas to be growing as more and more poured in through the outer cooling flow, but it wasn’t doing that. To all intents and purposes, it was mostly vanishing, with just a trickle carrying on down to lower and lower temperatures. It was as if the chain of cars rolling down the hill got a certain distance and then just conveniently disappeared. It felt like watching a great ocean liner gracefully sailing off to the horizon, and then suddenly turning into a dinghy before dropping out of sight.

Clearly, something was happening to all this gas. Perhaps an unknown mechanism was heating the gas in a targeted fashion, cooking up the cool stuff and getting it quickly back into the general mix before astronomers noticed it. Or perhaps, with the right arrangement of magnetic fields, thermal energy could be channeled to the cooling gas to warm it up—a great system of under-floor heating. The X-ray thermometer that astronomers were using relied on the precise mix of heavier elements like iron and oxygen with unpolluted gas. Fewer of those richer elements could skew the measurements at lower temperatures. Perhaps the just-cooled gas could be mixing up with either much hotter or much cooler gas, or could even be obscured by a hitherto unseen blanket of cool material that simply blocked the X-rays from our view.

There was another possibility. Maybe energy from a central supermassive black hole was halting the cooling. But how? The ability of a black hole to squirt out jets of particles, jets that could then splash out into great lobes of seething relativistic electrons and protons, was a tantalizing candidate. We knew that big central galaxies in clusters often harbored such structures. These were places where radio maps traced out colossal clouds and arcs of particles. Astronomers had certainly considered the impact these feeding black holes might have on the young galaxies and cooling gas we could see in the more distant universe. But something was needed in our neighborhood galaxy clusters: a clear signpost, something that could tell us exactly where to look. In the end there were several such signs, but one in particular is so big and clear that in retrospect it’s almost embarrassing that we hadn’t connected the dots before.

* * *

The answer begins with Perseus—not the monster slayer of Greek mythology, but a huge cluster of hundreds of galaxies, named for its sky placement in that hero’s constellation but actually located about 250 million light-years from our solar system. The Perseus cluster is one of the largest such structures in our cosmic neighborhood, and the brightest such object in X-rays from our viewpoint. If we could see it with our eyes, it would cover a patch of sky four times broader than the full Moon. Adding up all the stars, gas, and dark matter in this great agglomeration, it totals a staggering 700 trillion times the mass of our Sun—a thousand times the mass of the Milky Way. This huge collection is spread over a three-dimensional region that stretches across 12 million light-years. As in all such vast gravitational wells, the bulk of the normal matter in Perseus consists of gas at extraordinary temperatures. Heated to tens of millions of degrees, it glows with X-ray photons. Just as in all the other great clusters, the gas is trying to cool off. And just as in so many clusters, within the center is the unmistakable signature of particles that have been spewed out from around a supermassive black hole, glowing with radio emission.

A puzzle about Perseus had emerged in the early 1980s with its first detailed X-ray images. Perseus was great to look at—it was big and bright, and its glowing gas could be seen spread across hundreds of thousands of light-years, brighter toward the center and getting ever fainter toward the edges. But there was a strange dark zone in one corner of this huge structure, an area that looks like a dirty thumbprint on these images, blotting out perhaps a hundred thousand light-years of X-ray glow. A decade later, new telescopes and instruments revealed the same thing. Perseus had a gap in it. In 1993 the German astronomer Hans Boehringer used the latest data to begin to finally unravel the mystery. Within the core region of Perseus were two other vast dark hole–like gaps inside the hot, glowing gas. When Boehringer and his colleagues placed a map of the radio emission from Perseus over their new X-ray image, the two prominent lobes of radio light lined up almost perfectly with these voids in the gas.

There had been growing suspicion over the years that the high-speed particles injected into a cluster from a central black hole jet would have to push aside the cluster gas. Not only that, but they would constitute a far lower-density material than even the tenuous cluster plasma. This suggested that the inflating lobes of radio-emitting particles should be buoyant. If so, then they should quite literally float in the cluster. But it was not yet clear whether this could really happen. Perhaps these lighter bubbles would simply dissipate and fizzle out. Along with the enormous cooling flow puzzle, this was a huge question to answer. It was evident that we needed to take a very, very careful look deep inside one of these systems.

Fabian and his colleagues set out to study the Perseus cluster in unprecedented detail, using the Chandra observatory. After some intriguing initial results, they decided to go for broke. They needed the most precise image of Perseus possible. Only this would allow them to peel apart the data to get at the gold nuggets inside. Over the course of two years, they accumulated the data they needed, until they had almost 280 hours’ worth of photons—nearly a million seconds altogether—and from those they finally generated a new image of Perseus.

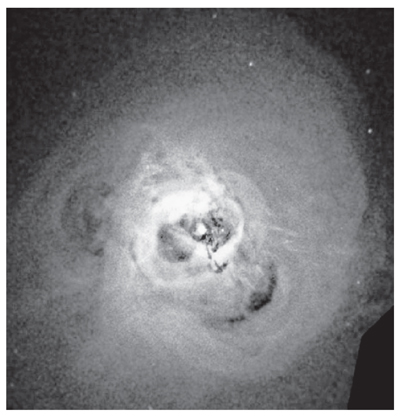

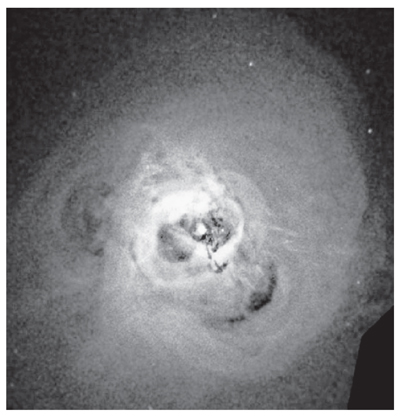

And what an image it was. With this incredible new visual fidelity, Perseus took on a whole new texture and flavor. It looked like a pond after a giant pebble has been thrown in, interrupting its smooth surface. There are clear bubble-like gaps, and there are ripples—actual waves through intergalactic space. All these are marching outward from the supermassive black hole at the core.

Fabian’s team looked at the data every way they could, holding it up like a faceted diamond to see the shifting colors and projections from within. The mysterious gaps high up in the outer regions of the cluster were indeed rising bubbles. Whatever highly energized particles the black hole had squirted out millions of years ago to inflate these forms had long since cooled down, invisible even to sensitive radio telescopes. But the particles live on, holding the cluster gas at bay. These are ghostly cavities in Perseus’s body, buoyant structures in a sea that is hundreds of thousands of light-years across. Down toward the core there are new bubbles, these still filled with hot electrons shedding radio-wave photons. The ripples between these floating bubbles are subtle, gentle structures. They are actual sound waves, the booming call of a leviathan. The time it takes for light to travel from one wave crest to the next is equivalent to the passage of all recorded human history.

Figure 14. An X-ray image of the hot gas in the inner regions of the Perseus galaxy cluster, showing the dark bubbles that have been blown by the black hole at the center and the great ripples of sound waves set in motion across the structure. At the very center are signs of some darker, cooler gas, looking like dirty strands of coagulated matter.

* * *

Fabian himself is an avid rower. More often than not, if you’re taking a morning stroll along the banks of the River Cam passing through Cambridge, you’ll spot his boat skimming along the gently flowing water, its V-shaped ripples expanding outward, lapping softly at the riverbank. Watch him move upriver, and you see the same processes at work that are taking place in Perseus. As the boat pushes and displaces the fluid around it, some of that energy dissipates across the water, far away from its source. The lap and splash of the shoreline waves comes from energy that is generated within the muscle fibers of human arms and transferred across a river’s surface. The supermassive black hole in a cluster core does the very same thing.

These structures in Perseus help us understand how the central supermassive black hole holds cooling matter at bay. The buoyantly rising bubbles can lift and push cooling gas aside, preventing it from funneling all the way down to the core. And like a vast musical organ, the bubbles set sound waves in motion that can disperse energy throughout Perseus, keeping it at a perfect simmer. We don’t yet know if these rippling pressure waves, like the rolling thunderclaps of a distant storm, are entirely responsible for halting the flow of cooling gas into Perseus’s inner core. But if we carefully measure these waves and compute how much energy they can push out across the cluster, it is certainly enough to balance out the energy that the cooling gas loses in X-rays.

A simple physics experiment brings the principle to life: place an open loudspeaker from a music system so that the speaker is on its back, forming a shallow cup. Put a sprinkling of sand or rice grains on the speaker. They roll and slither down to the middle. But then play music through the speaker with the volume turned up, perhaps a good bit of Bach or some heavy metal. The bass notes (or longer sound waves) vibrate the speaker and push at the grains. If you find the right pitch and volume, they’ll spread back out up the sides of the cup, bouncing and agitated and unable to slump to the center, just like the gas in Perseus.

Every few million years a supermassive black hole in Perseus is being fed matter. When this happens, an outburst of energy from its jets and radiation inflates bubbles of high-pressure, fast-moving particles into the comparatively cooler and denser gas of the cluster. As these bubbles inflate, they act like the vibrating blast from a massive pipe organ, pushing off a rippling pressure wave that spreads out across the system. As it passes it releases energy into the gas, helping to prevent it from cooling and rushing inward. The black hole is driving the ultimate subwoofer, an audiophile’s fantasy. The note it’s playing? Fifty-seven octaves below B flat above middle C, in case you were curious. That’s approximately 300,000 trillion times lower in frequency than the human voice. And the power output is a planet-disintegrating 1037 watts. Supermassive black holes can make you a very, very nice sound system.

We now know that Perseus is not the only place where this is happening: there is evidence for bubbles in 70 percent of all galaxy clusters. Here, too, the deep booming notes of these systems and their rippling undercurrents help moderate and regulate the cooling and inflow of gas. Here, as well as in isolated galaxies, we see evidence for a dynamic balance in the struggle between matter trying to build structures and the forces of disruption. In engineering this is called a “feedback loop.” A simple example is a device used for centuries to regulate the speed of engines, from those driven by windmills on into the era of steam power. The centrifugal or “flyball” governor is a pair of opposing metal balls hanging like twin pendulums on stiff wires from a vertical rod. The rod is connected to the spinning axle of an engine. The faster the engine runs, the faster this vertical rod spins, and the higher the two metal balls rise as centrifugal forces push at them. But as they rise, the wires holding them can transmit that movement to a valve or throttle that slows down the engine and prevents it from running too quickly.

We think a similar thing happens with feeding black holes. In essence, the greater the amount of matter that falls toward the hole, the greater the energy output, and the harder it becomes for matter to reach the hole in the first place. This is the effect of the ripple-producing bubbles in a galaxy cluster. Although this serves to slow down the black hole gravity engine, it’s rather sporadic and jerky. Unlike a beautifully smooth mechanical governor, a piece of high engineering from the Industrial Revolution, the fluid and fickle nature of gas and astrophysics results in something unique every time. Occasionally, a particularly dense patch of gas or stars manages to cool through to the core of a galaxy and descend into a black hole’s grasp. The hole flares up brilliantly and squirts out a bubble-inflating jet for a million years before running out of fuel. At other times, there may be just enough gas to trigger a mild response.

In clusters where a trickle of gas manages to cool all the way down before being heated and rearranged, there are ethereal fingerprints. Astronomers’ images in optical, ultraviolet, and infrared light reveal wispy threads and filaments of dense, warm material, cobweb-like structures of luminosity around the central zones of these clusters, no longer emitting X-rays. The cluster Perseus contains such forms within its central elliptical galaxy. Reaching across tens of thousands of light-years, they appear like strands of curdling milk in a great vat of matter. At the enormous distances of galaxy clusters it is impossible for us to see individual stars. They all merge into fog-like hazes. Nonetheless, by examining the spectral fingerprint of these milky filaments, we can tell that in among them are young large blue stars. The only viable explanation is that they are forming here, the end point in the journey of intergalactic gas that has settled its way down through the cluster. For now, escaping the petulant fist-waving of the supermassive black hole, it finishes as a warm nebula that then cools further to make new stellar systems. Eventually, these may be fodder for the next cycle of black hole activity, but not yet.

In the places where this happens, as much as a few times the mass of our Sun is converted from gas into stars every year. This rate provides a good match to the overall proportions of stars to gas in these central cluster galaxies. This is strong evidence that the reason we see the number of stars that we do in these galaxies is because the black holes are controlling the production line. The balance set by nature in these great systems of feedback is literally written in the stars. And that point of impasse stems from the fundamental nature of black hole physics, from electromagnetism to curved, spinning spacetime.

Here then, in the special environments of galaxy clusters, are clues to one of the major routes by which the universe builds new stars and galaxies. It is a startling display of how a supermassive black hole functions as a cosmic regulator, making sure the porridge of intergalactic matter is not too hot and not too cold. There is still much to learn about these mechanisms. There are indications that the supermassive black holes in the cores of clusters like Perseus may also be the fastest spinners. Faster-spinning holes are more efficient at producing energy. It makes sense: cluster-bound holes are the end recipients of a vast reservoir of intergalactic matter. If they weren’t big and efficient at pushing back, we would see far more cooling gas converted into stars, and it would be a very different universe if that had been the case.

Massive black holes are also clearly present in the cores of other galaxies, including those that are not part of bigger clusters. The most powerful jets in these systems have little surrounding medium into which to blow bubbles, and much of that energy simply sprays out to intergalactic space. But the fearsome glow of radiation and particles from the material accreting around the holes must still impact the surrounding environment. The next step for us is a big one. If we want to complete the story of black holes and the cosmic struggle between construction and destruction, we need to travel even farther. To finish the recipe for apple pie, we need to visit the remotest edges of the universe itself.