We have all had these intuitions, these breathings, of awe at being fearfully and wonderfully made, and it is our natural instinct to assume a maker of such intricacy, which our developed minds may hardly believe to have come about by blind chance. The Psalmist here forestalls the theorists of development by his knowledge of the perfection of substance and the continuous fashioning which goes to make living beings. He writes earlier of God’s loving care of the unborn infant, in verse 13, ‘For thou hast possessed my reins: thou hast covered me in my mother’s womb.’ It is not unreasonable to ask in what way such a Deity differs from that force which Mr Darwin calls Natural Selection, when he writes, ‘It may be said that natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinising, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is bad, preserving and adding up all that is good; silently and insensibly working, whenever and wherever opportunity offers, at the improvement of each organic being …”

Is not this watchful care another way of describing the providences through God’s grace in which we have traditionally been taught to believe? Might we not indeed argue that Mr Darwin’s new understanding of the means by which these providential changes are brought about is in itself a new providence contributing both to human advance and development, and to our capacity to wonder at, to know, to further and repair those forces which God has set in motion, and which Mr Richard Owen has described as the ‘continuous operation of ordained becoming’. Our God is not a Deus Absconditus, who has left us darkling in a barren waste, nor is He an indifferent Watchmaker, who wound up a spring and looks on without passion as it slowly unwinds itself towards a final inertia. He is a loving craftsman, who constantly devises new possibilities from the abundant graves and raw materials he gave to them.

We do not have to be Pangloss to believe in beauty and virtue and truth and happiness and above all in fellow-feeling and in love, human and divine. Clearly all is not for the best in the best of all possible worlds, and it is the height of folly, of wishful thinking, to attempt to deduce God from the joyful skipping of spring lambs, or the brightness of buttercups, or even the promise of the rainbow in a thunderous sky, though the writer of Genesis does offer all men the image of the bow set in the cloud as a promise that while the earth remaineth, seed-time and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease. The Bible tells us that the earth is accursed, since the Fall of Man, the Bible tells us that the curse is lifted, in part, after the Flood, the Bible tells us that our own destructive natures may be redeemed, are redeemed by the ransom paid by our Lord, Jesus Christ. The face of the earth does not always laugh, even if it speaks God to us through the mouths of stones and flowers, tempests and whirlwinds, or even the lowly diligence of ants and bees. And we may discuss, if we wish, an amelioration of our own cursed natures, working itself out in our daily lives, with many a setback, many a struggle, since the day when Our Lord bade us ‘Love our neighbours as ourselves’ and revealed Himself as God of Love as well as of Power and of special Providence.

Let us, like Him, speak in parables. His parables are drawn from the mysteries of that Nature, of which, if we are to believe His Gospel, He is Maker and Sustainer. He speaks to us of the fall of sparrows and the lilies of the field who toil not, neither do they spin. He speaks to us—even He—of that wastefulness of Nature which so appals the Laureate, in His parable of the seeds which fell among weeds or on stony ground. If we consider the humble lives of the social insects I think we may discern truths which are riddling paradigms for our own understandings. We have been accustomed to think of altruism and self-sacrifice as human virtues, essentially human, but this is not apparently so. These little creatures exercise both, in their ways.

It has long been known that amongst the nations both of the bees and of the ants, there is only one true female, the Queen, and that the work of the community is carried on by barren females, or nuns, who attend to the feeding, building, and nurturing of the whole society and its city. It has also long been known that the insects themselves seem able to determine the sex of the embryo, or larva, according to the attention they pay to it. Chambers tells us that the preparatory states of the Queen Bee occupy 16 days; those of the neuters 20; and those of the males 24. The bees appear to enlarge the cell of the female larva, make a pyramidal hollow to allow of its assuming a vertical instead of a horizontal position, keep it warmer than other larvae are kept, and feed it with a peculiar kind of food. This care, including the shortening of the embryonic condition, produces a true female, a Queen who is destined, in the noteworthy words of Kirby and Spence ‘to enjoy love, to burn with jealousy and anger, to be incited to vengeance, and to pass her time without labour’. Mr Darwin has confessed to his distress at the savagery with which the jealous Queens watch over, and murder, their emerging sisters in the beehive. He questioned whether this murder of the new-born, this veritable slaughter of the innocents, did not argue that Nature herself was cruel and wasteful. It could conversely be supposed that a special providence lay in the survival of the Queen best fitted to provide the hive with new generations, or the swarm with a new commander. Be that as it may, it is certain that the longer development of the worker produces a very different creature, one, again in Kirby and Spence’s words ‘zealous for the good of the community, a defender of the public rights, enjoying an immunity from the stimulus of sexual appetite and the pains of parturition; laborious, industrious, patient, ingenious, skilful; incessantly engaged in the nurture of the young, in collecting honey and pollen, in elaborating wax, in constructing cells and the like!—paying the most respectful and assiduous attention to objects which, had its ovaries been developed, it would have hated and pursued with the most vindictive fury till it had destroyed them!’

I do not think it is folly to argue that the society of the bees has developed in the patient nuns who do the work a primitive form of altruism, self-sacrifice, or loving-kindness. The same is even more strikingly true of the sisterhood of ant-workers, who greet each other with great shows of affection and gentle caresses, always offering sips from their chalices of gathered nectar, which they are hurrying to carry to the helpless and dependent inhabitants of their nurseries. The ants too are able to determine, how is not known, the sex of the inhabitants of their nurseries, so that the community is replenished by desirable numbers of workers, males or fertile Queens at various epochs. Their care of their fellows might itself be thought to be a special Providence, if it were thought to be conscious, or a true moral choice. Much labour has been expended on attempts to distinguish the voice of authority in these communities—is it the Queen, or the workers, or some more pervasive Spirit of the City, located everywhere and nowhere, that determines these matters? What dictates the coherent movement of all the cells in my body? I do not, though I have Will, and Intelligence, and Reason. I grow, I decay, according to laws which I obey and cannot alter. So do the lesser creatures on the earth. How shall we name the Force that directs them? Blind Chance, or loving Providence? We churchmen have always in the past given one answer. Shall we now be daunted? Scientists attempting to ‘explain’ phenomena such as the growth of the ants’ embryos have resorted to the idea of a ‘forma formativa’, a Vital Force, residing perhaps in infinitely numerous gemmules. May we not reasonably ask, what lies behind the forming power, the Vital Force, the physics? Some physicists have come to speak of an unknown x or y. Is it not possible that this x or y is the Mystery which orders the doings of ants and men, which moves the sun and the other stars, as Dante recorded, across the Heavens—the Spirit, the Breath of God, Love Himself.

What is it that leads Mankind to yearn for the Divine Reassurance, the certainty of the Divine Care and the organising hand of the Divine Creator and Perpetuator? How should we have had the wit to devise such an aweful concept did not our own small minds correspond to some true Presence in the Universe, did we not dimly perceive and even more crucially NEED such a Being? When we see the love of the creatures for their offspring, or the tender gaze of a human mother bent on her helpless infant, which without her loving watchfulness would be quite unable to survive a day of hunger and thirst, do we not sense that love is the order of things, of which we are a wonderful part? The Laureate puts the terrible negative questions squarely in his great poem. He allows us to glimpse the new face of a world driven aimlessly by Chance and blind Fate. He presents, with plaintive singing, the possibility that God may be nothing more than our own invention, and Heaven a pious fiction. He gives the devil-born Doubt its full due, and makes his readers tremble with the impotent anxiety which is part of the Spirit of our Age.

Oh yet we trust that somehow good

Will be the final goal of ill,

To pangs of nature, sins of will,

Defects of doubt, and taints of blood;

That not one life shall be destroyed,

Or cast as rubbish to the void,

When God hath made the pile complete;

That not a moth with vain desire

Is shrivelled in a fruitless fire,

Or but subserves another’s gain.

I can but trust that good shall fall

At last—far off—at last, to all,

And every winter change to spring.

An infant crying in the night:

An infant crying for the light:

And with no language but a cry.

In the next poem, Mr Tennyson writes even more strongly of Nature’s cruelty and carelessness, she who cries, ‘I care for nothing, all shall go,’ and of Poor Man:

Who trusted God was love indeed

And love Creation’s final law—

Though Nature, red in tooth and claw

With ravine, shrieked against his creed—

And how does he answer this terrible indictment? He answers with the truth of feeling to which we must not be impervious, though it may seem childishly simple, naive, almost impotent. Can we accept this truth of feeling from the depths of our natures, when our intellects have been stunned and blunted by difficult questions?

I found Him not in world or sun,

Or eagle’s wing, or insect’s eye;

Nor through the questions men may try,

The petty cobwebs we have spun:

I heard a voice ‘believe no more’

And heard an ever-breaking shore

That tumbled in the Godless deep;

The freezing reason’s colder part,

And like a man in wrath the heart

Stood up and answered ‘I have felt.’

But that blind clamour made me wise;

Then was I as a child that cries,

But, crying, knows his father near;

What is, and no man understands;

And out of darkness came the hands

That reach through nature, moulding men.

Was it not a true leading that enabled Mr Tennyson to become again as a little child, and feel the Fatherhood of the Lord of Hosts? Was it not significant that the warm organised cells of his heart and his circulating blood rose up against the ‘freezing reason’? The infant crying in the night receives not enlightenment, but the warm touch of a fatherly hand, and thus believes, thus lives his belief. We are fearfully and wonderfully made, in His Image, father and son, son and father, from generation to generation, in mystery and ordained order.

Harald had put up the cowl of his gown against the cold. His long face, on its scrawny neck, peered at William as he read, assessing the flicker of the other’s eyes, the compressions of his lips, the odd nod or shake of the head. When William had finished, Harald said, ‘You are not convinced. You do not believe—’

‘I do not know how I can believe or not believe. It is, as you most eloquently say, a matter of feeling. And I cannot feel these things to be so.’

‘And my argument from love—from paternal love?’

‘It is resonant. But I would answer as Feuerbach answers, “Homo homini deus est”, our God is ourselves, we worship ourselves. We have made our God by a specious analogy, Sir—I do not mean to give offence, but I have been thinking about this for some years—we make perfect images of ourselves, of our lives and fates, as the painters do of the Man of Sorrows, or the scene in the Stable, or as you once said, of a grave-faced winged Creature speaking to a young girl. And we worship these, as primitive peoples worship masks of terror, the alligator, the eagle, the anaconda. You may argue anything at all by analogy, Sir, and so consequently nothing. This is my view. Feuerbach understood something fundamental about our minds. We need loving kindness in reality; and often we do not find it—so we invent a divine Parent for the infant crying in the night, and convince ourselves all is well. In reality, many cries remain unheard in perpetuity.’

‘That is not a refutation.’

‘In the nature of the case, it cannot be. It leaves the matter exactly where it first stood. We desire things to be so, and so we create a tale, or a picture, that says, we are so and so. You might as well say, we are like ants, as that ants may develop to be like us.’

‘Indeed I might. We are all one life, I believe, shot through with His love. I believe, I hope.’

He took back his papers with careful hands, in which the papers shivered. The hands were ivory-coloured, the skin finely wrinkled everywhere, like the crust on a pool of wax, and under it appeared livid bruises, arthritic nodes, irregular tea-brown stains. William watched the hands fold the wavering papers and was fined with pity for them, as for sick and dying creatures. The flesh under the horny nails was candlewax-coloured, and bloodless.

‘It may be an emotional deficiency in myself, Sir, that I cannot feel the strength of the argument. I have been much changed by the pattern of my life, of my work. My own father was very much in the image of a terrible Judge, who preached rivers of blood and destruction, and whose own profession was bloody too. And then the vast disorder—the indifference to human scale and preoccupations—in the Amazon—I have not been left with a propensity to find kindness in the face of things.’

‘But I hope you have found it here. For you must know that we must count your coming as a special Providence—to make a new life for dear Eugenia, and now for your little ones—’

‘I am most grateful—’

‘And happy, I hope, contented, I hope,’ the tired old voice insisted in the sharp air, hanging there in a question.

‘Very happy, of course, Sir. I have all I wished for, and more. And when I come to think about my future—’

‘That shall be provided for, as you richly deserve, have no fears. There can be no thought of leaving Eugenia as yet—you would not so disappoint her—her happiness is young—but in due course, you will find all your needs can be answered, amply so, have no fears. I regard you as my dear son, and I intend to provide for you. In due course.’

‘I thank you, Sir.’

There was frost on the inside of the windows, and watery tears, involuntary damp, round the red rims of the clouded eyes.

William congratulated Miss Crompton on the scenery of this tour de force, when he met her next day, winding up the crimson ribbons and folding the tinsel of the Burning Bush.

‘It was easy to see whose was the inventive mind behind all these beautiful objects,’ he said.

‘I do what comes to hand, as well as I can,’ she said. ‘Such activities stave off boredom.’

‘Are you often bored?’

‘I try not to be.’

‘That is not an answer.’

‘I suppose we all feel we have greater capacities than are called for in our daily lives.’

She gave him her sharp look as she said this, and he had the uncomfortable feeling that she had only answered his intrusively personal question in order to draw him out. He was beginning to be a little afraid of Matty Crompton’s sharpness. She had never treated him other than very benevolently, and had never put herself forward in any way. But he sensed a kind of suppressed, fierceness in her which he was not wholly sure he wanted to know more about. She had herself very much in her own control, and he thought he preferred to leave things that way. However, he answered, because he needed to speak, and he could not speak to Harald or to Eugenia on these matters. It would be wrong. Wrong now, at least, wrong at this juncture.

‘I do feel something of the kind myself, from time to time. It is strange that in the Amazons I woke daily from a dream of mild English sunshine, of simple and wonderful things such as bread, and butter, instead of endless cassava. And now I wake from dreams of the forest curtain, of the movement of the river, of my work, Miss Crompton. I do not have my work, my own work here, though my life could not be more pleasant, nor my new family kinder.’

‘You work, I believe, with Sir Harald, on his book.’

‘I do, but I am not really needed, and my views—in short, my views do not wholly agree with his. He desires me to play advocatus diaboli to his arguments, but I fear I distress him and add little to the advancement of the work—’

‘Perhaps you should write your own book.’

‘I have no settled opinions to advance, and no wish to convert anyone to my own rather uncertain views of things.’

‘I did not mean opinions.’ There was a possible curl of contempt—he could not decide—in the incisive voice. ‘I meant a book of facts. A book of scientific facts, such as you are uniquely qualified to write.’

‘I have meant to write a book of my travels—such books have been very successful, I know—but all my detailed notes, all my specimens were lost in the shipwreck. I have not the heart to invent, if I could.’

‘But nearer to hand—nearer to hand, lie things you could observe and write about.’

‘You have suggested this before. I am sure you are right—I am most grateful to you. I do intend to begin a close study of the Elm Copse nests just as soon as they return to life in the Spring—but a scientific study will take many years, and much rigour, and I had hoped—’

‘You had hoped—’

‘I had hoped to be able to set out again on another foreign journey to collect more information about the untravelled world—I wish to do that—Sir Harald suggested, more or less promised, that he might be sympathetic—’

Matty Crompton closed her sharp mouth tightly. She said, ‘The book I should like to see you write is not a major scientific study. Not the work of a lifetime. It is a book I think might prove useful—and dare I say it—profitable to you, in the quite near future. I believe if you were to write a natural history of the colonies over a year—or two years, if you were to feel the need was absolute—you would have something very interesting to a very general public, and yet of scientific value. You could bring your very great knowledge to bear on the particular lives of these creatures—make comparisons—bring in their Amazonian relatives—but told in a popular way with anecdotes, and folklore, and stories of how the observations were made—’

She looked him in the eye. Her own dark eyes gleamed. He caught at her idea.

‘It might be interesting—it might be fun—’

‘Fun,’ said Miss Crompton. ‘The children could be usefully employed. I myself would be proud to assist. Miss Mead would do what she could. I see the children as characters in the drama. There absolutely has to be drama, you know, if the work is to appeal to the general public.’

‘You should write it yourself, I think. It is all your idea, and you should have the credit.’

‘Oh no. I have not the requisite knowledge—nor the spare time, though it is hard to say where my days go to—I do not see myself as a writer. But as an assistant, Mr Adamson, if you would accept me. I would be honoured. I can draw—and record—and copy if necessary—’

‘I am quite extraordinarily grateful. You have transfigured my prospects.’

‘Hardly. But I do believe it may answer. With good will and hard work.’

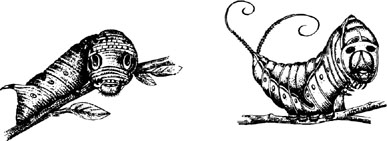

‘How anything can survive with a hair for a waist, puzzles me,’ she said. ‘They seem so vulnerable, with their bristling little feet and their delicate antennae, and yet they are armed with stings and savage jaws, they can slice and pierce as well as any knight in armour, and they are armoured moreover. What would you say to a few cartoon-like illustrations for your text—here, I have drawn one with a stiletto, and there with a staring helmet and a kind of heavy wrench.’

‘I should think it might add greatly to the human interest’, said William. ‘Have you observed how they can sever antennae and legs and cut each other in half so very quickly? And have you observed how many of the combatants advance to meet an adversary with several helpers clinging to their legs? Now, what possible advantage can such assistance be? Is it not rather an impediment?

‘Let me see,’ she said, dropping to her knees beside him. ‘Why, so they do. How endlessly interesting they are. See this poor soul bend round to sting an adversary who has a terrible vice-grip on her head. They will both die, like Balin and Balan, I should think.’

She was wearing a brown cotton skirt, and a striped shirt, the sleeves rolled up to her elbow. Her face was shadowed by a rather ragged straw hat, with a limp crimson ribbon, which were her usual ant-watching garments. He knew all her wardrobe by now; it was not extensive; two cotton skirts, a Sunday dress, in Summer, in navy poplin, with a choice of white starched collars, and perhaps four different shirts, in various fawns and greys. She was thin and bony; he found himself abstractedly studying her wristbones, and the tendons on the back of her brown hands, as she drew. Her movements were quick and decisive. A flick, a sweep, a series of little hooks and curves, and there was an exact diagrammatic rendering of ant-jaws crunching ant-legs, ant-thorax and ant-gaster contorted either in pain or in effort to inflict it. Beside these informative images trotted tiny anthropomorphised ant-warriors, with swords, bucklers, tridents and helmeted heads. She was absorbed in her work. William found himself suddenly sharply inhaling what must have been her peculiar smell, a slightly acid armpit smell, inside the cotton sleeves in the sunlight, mixed with a tincture of what might be lemon verbena, and a whiff of lavender, either from her soap, or from the herbs in the drawer where her shirts were laid up. He breathed more deeply. The hunter in him, now in abeyance, had a highly developed sense of smell. There were jungle creatures whose presence he sensed with all sorts of senses undeveloped in urban Englishmen, he supposed—a pricking in the skin, a fluctuation in the soft nasal lining, a ripple in the scalp, a perturbation of his sense of balance. These had tormented him in London streets, where they had over-responded to fried onions and sewage, to the garments of the urban poor and the perfumes of ladies. He sniffed again, secretly and quietly, the scent of Miss Crompton’s outdoor identity. Later in Eugenia’s bedroom, when she had reclaimed him, and he was buried in the smells of her fresh sheets and her fluid sex, her hot hair and her panting mouth, that sharp little smell returned briefly like a ghost of the outdoors, and he puzzled for a moment, as he pressed Eugenia into the plump mattress, over what it could be, and remembered the severed feelers and Matty Crompton’s busy wrists.

William and Matty sallied forth, armed with camp-stools and notebooks, and were there in time to observe the slave-makers’ forces, after a great deal of excited waving of antennae and legs and apparently inane running-about, suddenly get out, purposefully, led by an advance guard of particularly excited scouts, across the thirty yards or more that separated their smaller mounds from the Elm Tree Bole. They poured out in various regiments, accompanied, as William duly noticed, by a sizeable force of Wood Ant slaves, whose behaviour appeared to be identical to that of their masters.

William wrote up what they observed, and read it aloud later to Matty Crompton and the rest of the inhabitants of the schoolroom.

The great Slaving Raid took place on a hot June day, when the temperature had been rising steadily for some time, and with it the activities of the Blood-red Ants, as reported to our historians by our spies and pickets. We were led to speculate whether slave-raids, like other large exoduses and population changes, are instigated by the heat of the Sun. Ants do not move in cool weather, and sleep at night, even in the balmiest Summer days; they are cold-blooded, and need external warmth to get their desires and designs in motion. Be that as it may, the approach of Midsummer roused the Blood-red citizens to an increasing hum of conversation and activity. Messages came in more and more speedily and frequently. More and more scouts could be seen spying on the peaceful foraging of the Wood Ants, or busily trampling out trails between their nest and that of their unsuspecting victims.

Finally, at some signal, awaited eagerly by the gossiping and seething crowds who had rushed in readiness to the agora on their hill-top, the red armies divided into four parties, which set out in direct lines across the terrain—following well-mapped routes, used, we suspected, on previous raids. When the four regiments had taken up their positions around the Elm Tree Bole Nest, the leaders of all four could be observed like little Napoleons rushing excitedly along the ranks, stirring up valour and determination with strokes of their antennae and agitated bodily movements. Suddenly the 1st Sanguine Troopers moved into concerted action, storming their way towards the entrances—so carefully barricaded at night, now gaping open to the incitatory sunlight. The 2nd, 3rd and 4th Regiments patrolled the positions they had taken up, with increasing forcefulness and ferocity.

The Wood Ants sallied forth bravely to beat off the thieves and kidnappers. Waving their antennae, hurrying furiously, they bit at the legs and heads and feelers of the busy Bloody Ants, attempting, often with success, to grasp the invaders and sting them to death. We observed that the Sanguine Ants did not retaliate unless they were wholly impeded from progress. They had one purpose only—to snatch the unhatched infants from the Nursery, and to bear them back, in their fine jaws, to their own fortress. Whilst the martial Wood Ants battled to delay them, the tenders of the helpless young snatched up their infant sisters and tried to bear them away to safety. Most strange was to see Wood Ants, identical in appearance to the inhabitants of Elm Tree Bole, rushing forwards into the corridors of the castle, seizing cocoons and bearing them, not to safety, but out again to the ramparts and the waiting, protective corps of sanguinea who would be the rearguard for their safe passage back to the Red Fort. We were sufficient in numbers, as observers, to make quite sure, from repeated trackings of individual sanguinea and Wood Ants, that the residents of Elm Tree Bole did not distinguish between the ruddy foreigners, and their slaves of their own race, attacking both impartially.

It was all over remarkably quickly. There were very few casualties. The Blood-red Ants had not come to slaughter, and had moved so swiftly, so single-mindedly, that the Wood Ant defenders—retaliating as they would to aggressive territorial invasions by their own kind—had been baffled and bewildered, and had allowed their attackers to make their limited assault without very effective opposition. Back streamed the victorious invaders, carefully bearing the captured nestlings whose fate was to live and die as sanguinea, not as true Wood Ants, to feed and nourish little sanguinea, to respond to the Summer sun by massing to attack their forgotten parents and sisters. They do not appear to have depleted the nursery inhabitants so severely as to disrupt the way of life of the Elm Tree Bole, which resumed, after the excitement, much as it had been. They did not, as human soldiers do, rape and pillage, loot and destroy. They came, and saw, and conquered, and achieved their object, and left again. It is believed that slave-making raids are made not more than once a year, so we were lucky to have—as the Red Ants themselves did—good spies to alert us to this interesting event.

The English slave-makers are not so specialised as certain other larger slave-makers are. These are known as the Amazons, though they do not originate in the Amazon basin but are commonly found in Europe and North America. The Amazona—for example Polyergus rufescens—never excavate nests nor care for their young. Their name is probably bestowed because like the classical Amazon warriors, who were all women, led by a fierce queen, they have substituted belligerence for the delicate domestic virtues associated with the female sex. Unlike the Blood-red Ants, the Amazons have developed such powerful tools and weapons of fighting and thieving that they are unable to perform any other function, and depend entirely on their slaves to feed them and polish their ruddy armour. Their jaws cannot seize prey; they have to beg their slaves for food; but they can kill, and they can carry. It might be argued that Natural Selection has perfected these creatures as fighting machines, but in the process has rendered them irrevocably dependent and parasitic. We may ask if there are not lessons to be learned by ourselves from this curious and extreme social state.

‘Nature does indeed teach us,’ said Miss Mead. ‘A terrible war is being waged at present across the Atlantic, to secure not only the liberation of the unfortunate slaves, but the moral salvation of those whose leisure and enrichment are sustained by their cruel labours.’

‘And we are urged’, said Matty Crompton, ‘to fight on the side of the slave-makers, to preserve the work, that is the daily bread, of our own cotton-mill workers. And our own philanthropists, in turn, seek to rescue those machine-slaves from their specialised labour. I do not know quite where these thoughts may lead us.’

‘Analogy is a slippery tool,’ said William. ‘Men are not ants.’

We were fortunate also, in 1862, to be able to observe the spectacle of the wedding dance of the thousands of winged Queens and aspiring suitors, who swarmed on the Osborne Nest and the Elm Tree Bole as if at a given signal, a trumpet-sound, or the resonant hum of a gong. Vigilant young eyes had observed young males attempting to leave the nest some days earlier, and being held back by determined guardians until the appointed time. We had had some idea when that might be, for we had noted the exact date of the nuptial ceremonies during the previous Summer, when the whirling couples had plummeted, like so many Icaruses or falling angels, to a creamy suffocation, or death by drowning in a steaming cauldron of fragrant Mysore in the midst of our own strawberry picnic. The appointed day in 1862 was the 27th June, and the ball-guests emerged in clouds of gauze and took to the air in fragile spires. Many ants consummate their unions in flight, embracing each other high above the earth. The Wood Ants appear to mate in fact on the earth—the males of this species are nearer in size to the Queens than in many others, where the Queen may exceed her consort by twenty times or more in bulk, and can easily transport her lover through the empyrean. We were unable on this occasion to observe whether the Wood Ant Queen practises polyandry, though other species of ants are known to do so—we hope to be able to observe more closely next year. We did observe heaps of fiercely struggling and battling black bodies, wrapped in their diaphanous veiling, each Queen fought for by ten or twenty determined suitors, who will hang fiercely on to each other’s legs, to get a purchase anywhere at all—more like a battle in Rugby Football than the elegant minuet for which their silky robes might seem fitted. The little workers stand by and observe, occasionally pulling at one or other of the actors in this passionate drama. We might imagine them feeling a certain complacency at their immunity from the terrible desire, both murderous and suicidal as well as amorous, which drives the winged sexual creatures. They appear also to feel a certain organising interest in things going well, and will give a pull or a push or a tweak to one or other of the embracing combatants—we could not ascertain the purpose of these interventions, though in other breeds of more primitive ant, where mating takes place in the nest, the workers are known to control the access of the males to the Queens, choosing which shall be admitted to their presence and which shall be kept at bay with jaws and sting.

How busy, how festive, how happy the dancing seemed! How tragic its outcome for almost all of the participants! The nuptial flight of the Wood Ants offers a supremely moving example of the inexorable secret work of Natural Selection, so that anyone observing it must be struck by how completely Mr Darwin’s ideas might seem to explain it. The males struggle mightily to possess the winged Queens; they must prove their strength of flight, their combative skills, their powers of attracting and gaining the trust of the wary female, spoiled as she is by choice of an almost infinite number of pressing lovers. And the Queens themselves, who emerge in their hundreds of hundreds, must possess strength and skill and cunning and tenacity to survive more than a very few moments after successful fecundation, let alone to start a nest. The time in the blue sky, the dizzy whirling in the gauzy finery lasts only a few hours. Then they must snap off their wings, like a young girl stepping out of her wedding veils, and scurry away to find a safe place to found a new nest-colony. Most fall prey to birds, other insects, frogs and toads, hedgehogs and trampling humans. Few indeed manage to make their way again underground, where they will lay their first eggs, nourish their first brood of daughters—miserable dwarfs, fragile and slow, these early children—and in due course, as the workers take over the running of the nursery and the provision of food, they will forget that they ever saw the sun, or thought for themselves, or chose a path to run on, or flew in the Midsummer blue. They become egg-laying machines, gross and glistening, endlessly licked, caressed, soothed and smoothed—veritable Prisoners of Love. This is the true nature of the Venus under the Mountain, in this miniature world a creature immobilised by her function of breeding, by the blind violence of her passions.

And what of the males? Their fate, even more poignantly, exemplifies the remorseless random purposefulness of Dame Nature, of Natural Selection. It is believed that early males of primitive ants were also in some sense workers, members of the community. But as the Societies of insects became more complex, more truly interdependent, the sexual forms of the creatures involved became more and more specialised. It is not generally known that worker-ants can and do, upon occasion, lay eggs, from which, it appears, only male children will emerge. But they appear to do this only if the Queen is ailing, or the nest is threatened. In general the Queens mother the whole society, and have changed in body to be able to do so, swollen with eggs, enough eggs fertilised from this one matrimonial encounter for a whole generation. Changes in bodily form according to function exist throughout the insect societies. There are ants whose heads exactly fit to plug the holes in the stems of plants where they live, which when not plugged are entrances and exits. There are ants known as Repletes, hung up in cellars like living wineskins, bloated with stored nectar. And the males, too, have become specialised, as factory-hands are specialised hands for the making of pin-heads or brackets. Their whole existence is directed only to the nuptial dance and the fertilisation of the Queens. Their eyes are huge and keen. Their sexual organs, as the fatal day approaches, occupy almost the whole of their body. They are flying amorous projectiles, truly no more than the burning arrows of the winged and blindfold god of Love. And after their day of glory, they are unnecessary and unwanted. They run hither and thither, aimlessly, draggle-winged. They are beaten back for the most part from the doors of their home nests, and driven away to mope and die in the cooling evenings of late Summer and early Autumn. Like the drones of the beehive they toil not, neither do they spin, though like the drones too, they are pampered in the early stages of their lives, tolerated pretty parasites, who dirty and disturb the calm workings of the nest, who must be fed on honey-dew and cleaned up after in the corridors. The drones, too, as Autumn approaches, meet with a terrible fate. One morning in the hive a mysterious Authority arms and alerts the worker-sisters, who descend on the sleeping hordes of velvet slugabeds, and proceed to tear them limb from limb, to pierce, to sever, to blind, to bundle bleeding out of doors, and remorselessly to refuse readmission. How profligate is Nature of her seeds, of her sons, making thousands that one may pass on his inheritance to sons and daughters.

‘Very eloquent,’ commented Matty Crompton, drily. ‘I am quite overcome with pity for these poor, useless male creatures. I must admit I had never seen them in that light before. Do you not think you may have been somewhat anthropomorphic in your choice of rhetoric?’

‘I thought that was our intention, in this History. To appeal to a wide audience, by telling truths—scientific truths—with a note of the fabulous. I have perhaps overdone it. I could tone it down.’

‘I am quite sure you should not—it will do excellently as it is—it will appeal greatly to the dramatic emotions—I have had an idea of writing some real fables of my own, to go with my little drawings of mestizo fairy-insects. I should like to emulate La Fontaine—the tale of the grasshopper and the ant, you know—only more accurately. And I have been making a collection of literary citations in a commonplace book, which I thought might be placed at the head of your chapters. It is important that the book be delightful as well as profound and truthful, is it not? I found a wonderful sonnet by poor mad John Clare, which, like Milton’s Pandemonium-beehive, seems to suggest that our idea of fairies may be only an anthropomorphising of insects. I like your Venus under the Mountain. She is related to the Little People under the Hill of all British fairy lore. I am convinced that many of the flying demons on church walls are inspired by stag beetles with their brows. How I go on! Here is the Clare. Tell me what you think. Rulers and labourers alike were men to him, you will see.’

What wonder strikes the curious, while he views

The black ant’s city, by a rotten tree

Or woodland bank! In ignorance we muse:

Pausing, annoyed, we know not what we see,

Such government and thought there seem to be;

Some looking on, and urging some to toil,

Dragging their loads of bent-stalks slavishly;

And what’s more wonderful, when big loads foil

One ant or two to carry, quickly then

A swarm flock round to help their fellow-men.

Surely they speak a language whisperingly,

Too fine for us to hear; and sure their ways

Prove they have kings and laws, and that they be

Deformed remnants of the fairy-days.

She was keen, she was resourceful, William thought. He half-wished he could confide in her about his own drone-nature, as he increasingly perceived it, though that, of course, was impossible for all sorts of reasons. He could not betray Eugenia, or demean himself by complaining of Eugenia. Moreover, to complain in this way would make him look foolish. He had yearned for Eugenia, and he had Eugenia, and he was bodily in thrall to Eugenia, as must, in this confined community, be apparent even to a sexless being like Miss Crompton.

It interested him, that he thought of her as sexless. That thought itself might have arisen out of some analogy with the worker ants. She was dry, was Matty Crompton. She did not, he was coming to see, suffer fools gladly. He was beginning to think that there were all sorts of frustrated ambitions contained in that sharp, bony body, behind those watchful black eyes. She was determined and inventive about the book. She was fiercely intent, not only on its production, but on its success. Why? He himself had an unspoken, almost unacknowledged vision of making enough money to be able to set out again for the Southern Hemisphere independent of Harald and Eugenia, but Miss Crompton could not want that, could not know that he wanted that, could not want him to go, when he added so much to the interest of her life. He did not think she was so altruistic a being.

‘I know nothing about Edgar’s private life.’

‘A veritable centaur, or do I mean a satyr? A man of appetites—no girl is safe, they say, except the most unimpeachably respectable young creatures, who innocently set their caps at him and whom he avoids like the plague. He likes a rough and tumble, he says. I don’t think a man should behave as he does, though there’s no denying plenty do, maybe most.’

William, about to be righteously indignant, remembered various golden, amber and coffee-skinned creatures he had loved on hot nights—and smiled awkwardly.

‘Wild oats,’ said Robin Swinnerton, ‘according to Edgar, are stronger and more savoury than the cultivated kind. I always meant to save myself, to commit myself—to one.’

‘You have not been married long,’ said William uncomfortably. ‘You should not lose hope, I am sure.’

‘I do not,’ said Robin. ‘But Rowena is downcast, and looks somewhat enviously at Eugenia’s bliss. Your little ones are very true to type—veritable Alabasters.’

‘It is as though environment were everything and inheritance nothing, I sometimes think. They suck in Alabaster substance and grow into perfect little Alabasters—I only very rarely catch glimpses of myself in their expression—’

He thought of the Wood Ants enslaved by the sanguinea, who believed they were sanguinea, and shook himself. Men are not ants, said William Adamson to himself, and besides, the analogy will not do, an enslaved Wood Ant looks like a Wood Ant, tho’ to a sanguinea it may smell Blood-red. I am convinced their modes of recognition are almost entirely olfactory. Though it is possible they navigate by the sun, and that is to do with the eyes.

‘You are dreaming,’ said Robin Swinnerton. ‘I propose a gallop, if you are agreeable.

He wondered if he should retreat. Amy made an inarticulate cry. Edgar said, ‘I didn’t know you had an interest in this little thing.’

‘I don’t. Not a personal one. In her general wellbeing—’

‘Ah. Her general wellbeing. Tell him, Amy. Was I hurting you? Were my attentions unwelcome, perhaps?’

Amy was still bent back over the sink. Edgar withdrew his arm from her clothing with the deliberation of a trout-tickler leaving a trout stream. His fingermarks could be seen on Amy’s skin, round her mouth and chin. She gasped. ‘No, sir. No, sir. No harm. I am quite well, Mr Adamson. Please.’

William was not clear what the plea meant. Perhaps she was not clear herself. In any case, Edgar stepped back, and she stood up, head hanging, hands nervously rearranging her buttons and waistband.

‘I think you should apologise, Sir, and leave us,’ said Edgar coldly and heavily.

‘I think Amy should run away,’ said William. ‘I think she would do best to run away.’

‘Sir?’ said Amy in a very small voice, to Edgar.

‘Run off then, child,’ said Edgar. ‘I can always find you when I want you.’

His large pale mouth was unsmiling as he said this. It was a statement of fact. Amy ducked a vague obeisance at both men, and scuttled away.

Edgar said, ‘The servants in this house are no concern of yours, Adamson. You do not pay their wages, and I’ll thank you not to interfere with them.’

‘That little creature is no more than a child,’ said William. ‘And one who has never had a childhood—’

‘Nonsense. She is a nice little packet of flesh, and her heart beats faster when I feel for it, and her little mouth opens sweetly and eagerly. You know nothing, Adamson. I have noticed you know nothing. Go back to your beetles, and your creepy-crawlies. I won’t hurt the little puss, you can believe. Just add a bit of natural spice. Anyway, it’s none of your business. You are a hanger-on.’

‘And I have yet to learn what use you are to the world, or anyone in it,’ said William, his temper rising. Surprisingly, Edgar laughed at this, briefly, and without a smile.

‘I told you,’ he said. ‘I have noticed you know nothing.’

And he pushed past William and went out to the stables.

THE SWARMING CITY

A Natural History of a Woodland Society,

its polity, its economy, its arms and defences,

its origin, expansion and decline.

William worked on it fairly steadily, and Matty Crompton read and revised the drafts, and made fair copies of the final versions. It had always been their intention to devote one more Summer to the checking and revision of the previous Summer’s observations. Two years’ data were better than one, and William wrote off with queries about comparative observations to various myrmecological parts of the world. The project of a publishable book was, by tacit consent, shared only by William and Miss Crompton: there was, in fact, no ostensible reason why this should have been so, but they both behaved from the beginning conspiratorially, as though the family should think of the ant-study as a family educational amusement, a gentleman’s use of leisure time, whilst they, the writers, knew differently.

The book took shape. The first part was narrative, a kind of children’s voyage of discovery into the mysterious worlds that lay around them. Chapter 1 was to be

THE EXPLORERS DISCOVER THE CITY

and William wrote sketches of the children, of Tom and Amy, of Miss Mead and her poetical comparisons, though he found himself unable to characterise either himself or Matty Crompton, and used a narrative voice that was a kind of royal or scientific We, to include both of them, or either of them, at given points in time. Miss Crompton brightened this passage considerably with little forgotten details of friendly rivalry between the little girls, or fragments of picnics carried off by the foraging ants.

The second chapter was

THE NAMING AND MAPPING OF THE COLONIES

and then followed the serious work of describing their workings:

Builders, sweepers, excavators.

The nursery, the dormitory, the kitchen.

Other Inhabitants: Pets, pests, predators,

temporary visitors and ant-cattle.

The Defence of the City: War and Invasion.

Prisoners of Love: The Queens, the Drones,

the Marriage flight and the Foundations

of new Colonies.

The Civic Order and Authority: What is the source

of power and decisions?

After this, William planned some more abstract, questioning chapters. He debated with himself on various possible headings:

Instinct or Intelligence

Design or Hasard

The Individual and the Commonwealth

What Is an Individual?

These were questions that troubled him, personally, as deeply as the questions of Design and the Designer troubled Harald Alabaster. He debated with himself on paper, not quite sure whether his musings were worthy of publication.

We might remark that there is a continuing dispute amongst human students of these interesting creatures as to whether they possess, singly or collectively, anything that can be called ‘intelligence’ or not. We might also remark that the attitude of the human student is often coloured by what he would wish to believe, by his attitude to the Creation in general, that is, by a very general tendency to see every other thing, living and inanimate, in anthropomorphic terms. We wonder about the utility to men of other living things, and one of the uses we make of them is to try to use them as magical mirrors to reflect back to us our own faces with a difference. We look in their societies for analogies to our own, for structures of command, and a language of communication. In the past both ants and bees have been thought to have kings, generals and armies. Now we know better, and describe the female worker-ants as slaves, nurses, nuns or factory-operatives, as we choose. Those of us who conclude that the insects have no language, no capacity to think, no ‘intelligence’, but only ‘instinct’ tend to describe their actions as those of automata, which we picture as little mechanical inventions whirring about like clockwork set in motion.

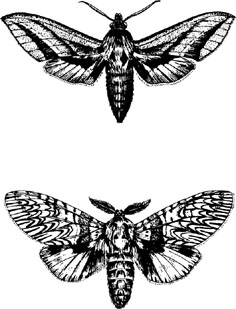

Those who wish to believe that there is a kind of intelligence in the nest and the hive can point to other things besides the marvellous mathematics of the hexagonal cells of the bees, which recent thinkers have decreed to be a function simply of their building movements and the shape of their bodies. No one who has spent long periods observing ants solving the problem of transporting an awkward straw, or a bulky dead caterpillar through the interstices of a mud floor, will feel able to argue that their movements are haphazard, that they do not jointly solve problems. I have seen a crew of a dozen ants manoeuvre a stem as tall, to them, as a tree to us, with about as many plausible false starts as a similar crew of schoolboys might make, before finding which end to insert at which angle. If this is instinct, it resembles intelligence in finding a particular method to solve a particular problem. M. Michelet in his recent book, L’Insecte, has a most elegant passage on the response to the plundering attacks of a lumbering moth, Sphinx Atropos, imported into France at the time of the American Revolution, probably as the caterpillar on the potato plant, protected and promulgated by Louis XIV. M. Michelet writes eloquently of the terrible appearance of this ‘sinister being’, ‘marked fairly precisely in wild grey with an ugly death’s-head’—it is our Death’s-head Hawk Moth, in fact. It is a glutton for honey, and pillages the hives, consuming eggs, nymphs and pupae in its depredations. The great Huber decided to protect his bees and was told by his assistant that the bees had already solved the problem either with, for instance, a variety of experimental barriers—by building new fortifications with narrow windows which would not admit the fat invader—or by making a series of barriers with successive walls zigzagging behind narrow entries, making a kind of twisting maze into which the Death’s-head could not insert its bulk. M. Michelet is delighted by this—it proves the bees’ intelligence, to him, conclusively. He calls it ‘the Coup d’État of the beasts, the insect revolution’, a blow struck not only against the Death’s-head but against thinkers like Malebranche and Buffon who denied bees any power of thought or capacity to divert their attention in new directions. Ants too can both make mazes and learn man-made mazes—some ants better than others. Do these things prove the little creatures are capable of conscious development? The order of their societies is infinitely more ancient than our own. Fossil ants are found in the most ancient stones; they have conducted themselves as they do over unimaginable millennia. Are they set in their ways—however intricate and subtle these may be—do they follow a driving force, an instinctual pattern rigid and invariable as stone channels, or are they soft, ductile, flexible, malleable by change and their own wills?

Much, so much, almost all, depends on what we think this force, or power, or indwelling spirit we call ‘instinct’ is. How does ‘instinct’ differ from intelligence? We must all admire the miracle of inherited aptitudes, inherited knowledge in a founding Queen of a new ant-colony who has never been outside her parent-nest, who has never been digging, or food-gathering, yet is able to nourish her young, feed and care for them, construct her first home, open the pupal shells. This is inherited intelligence, and is part of the general thoughtfulness and intelligence diffused through the whole society, which gives to all a knowledge of how to answer the needs of all in the most suitable way. The debate between the proponents of instinct and the proponents of intelligence is at its sharpest in its consideration of the Vigilance on the part of the whole community which makes decisions as to how many workers, how many soldiers, how many winged lovers or virgin Queens a community may need at any given time. Such decisions take into account the available food, the size of the nursery, the strength of the active Queens, the deaths of others, the season, the enemies. If these decisions are made by Chance, then these busy, efficient communities are ruled by a series of happy accidents, so complex that Chance must appear to be as wise as many local deities: if this is automatic response, what would intelligence be? The intelligence that directs the activities of the founding Queen, or those of the mature worker, is the intelligence of the City itself, of the conglomerate which cares for the wellbeing of the whole, and continues its life, in time and space, so that the community is infinite and eternal, even if both Queens and workers are mortal.

We do not wholly know what we mean either by the word ‘instinct’ or by the word ‘intelligence’. We divide our own actions into those controlled by ‘instinct’—the sucking of a new-born infant at the breast, the swerve of the runner to avoid danger, the sniffing at our bread and meat to detect signs of dangerous putrefaction; and those controlled by ‘intelligence’—foresight, rational analysis, reflective thought. Cuvier and other thinkers compared the workings of ‘instinct’ with those of ‘habit’, and Mr Darwin has finely observed that in human beings ‘the comparison gives a remarkably accurate account of the frame of mind under which an instinctive action is performed, but not of its origin. How unconsciously many habitual actions are performed, indeed not rarely in direct opposition to our conscious will! yet they may be modified by the will or reason.’ Are we to see the actions of the ants and bees as controlled by a combination of instincts as undeviating as the swallowing and swimming motions of the amoeba, or are we to see their behaviour as a combination of such instincts, acquired habits, and a directing intelligence, not residing in any particular individual ant, but accessible by these, when needed? Our own bodies are controlled by such a combination. Our own nerve-cells respond to stimuli and respond very strongly to the excitements of great fear, love, pain or intellectual activity, often arousing in us the possibility of new exercises of our skills previously unheard of. These are deep questions, pondered by every generation of philosophers, answered satisfactorily by none. Where do the soul and the mind reside in the human body? Or in the heart or in the head?

And do we find the analogy with our individual selves more useful, or that with the co-operative cells of our bodies, when understanding the ants? I believe I have been able to observe individual ants who habitually moved more vigorously and nervously, explored farther, approached other ants to interest them in new activities or to exhort them to greater efforts. Are these restless and inventive individual persons in the society, or are they large and well-fed cells in the centre of the ganglia? My own inclination is to wish to think of them as individual creatures, full of love, fear, ambition, anxiety, and yet I know also that their whole natures may be changed by changes in their circumstances. Shake up a dozen ants, in a test-tube, and they will fall on each other and fight furiously. Separate a worker from the community, and she will turn in aimless circles, or crouch morosely in a coma and wait to die: she will not survive for more than a few days at most. Those who argue that ants must blindly behave as ‘instinct’ dictates are making of ‘instinct’ a Calvinist God, another name for Predestination. And those observing similar reactions in human creatures, who may lose their wills and their memories after physical injuries or shocks, who may be born without the capacity to reason which makes us human—or may lose it, even, under the pressure of extreme desire, or extreme fear of death—are substituting the Predestination of body and instinct for the iron control of a loving and vengeful Deity on a golden immutable Throne in a Crystal Heaven.

The terrible idea—terrible to some, terrible, perhaps, to all, at some time or in some form—that we are biologically predestined like other creatures, that we differ from them only in inventiveness and the capacity for reflection on our fate—treads softly behind the arrogant judgement that makes of the ant a twitching automaton.

We may see their communities as the true individuals, of which the independent creatures, performing their functions, living and dying, are no more than cells, endlessly replaced and renewed. This would fit with Menenius’ fable in Coriolanus of the commonweal as a body, all of whose members help its continued life and wellbeing, from the toenails to the voracious belly. Professor Asa Gray, in Harvard University, has argued persuasively that in the case of the vegetable world, as in the branching animal communities of corals, it is the variety that is the individual, since the creatures may be divided and propagated asexually, without loss of life. The ant community is more varied than the corals, in the division of labour, and the variety of forms taken by the creatures, but it is possible to believe that its ends are no more complex and do not differ. They are the perpetuation of the city, the race, the original breed.

I made a Belgian friend in my travels on the Amazon, who was a good naturalist, a poet in his own language, and much given to meditation on the deeper things in life. He wrote despondingly of the effects on social animals of the very high elaboration of the social instinct which developed, he claimed, for the most part, from the family, the relations of mother and child, the protective gathering of the primal groups. He was in the jungle because he was not a social being, but a natural solitary, a romantic would-be Wild Man, but his observations on these matters are not uninteresting. The more perfected the association, he said, the more probability there is of a development of severe systems of authority, of intolerance, constraints, proliferated rules and regulations. Organised societies, he said, tended to the condition found in factories, in barracks, in the galleys, without leisure, or relaxation, using creatures pitilessly for their functional benefit, until they were exhausted and could be cast aside. Such social being he characterised memorably as ‘a kind of common despair’ and he saw the cities of the termites, in which fellow creatures are rationally turned to food when no longer useful, as a parody of the terrestrial Paradises towards which the social designers of human cities and communes are working so hopefully. Nature, he said, does not desire happiness. When I retorted that Fourier’s communities were based upon the rationally indulged pursuit of pleasures and inclinations (1,620 passions, to count exactly), he said gloomily that these groups were doomed to failure, either because they would disintegrate into combative chaos, or because the rational organisation would substitute militarism for Harmony, sooner or later.

I retorted at the time that Réaumur claimed to have observed ants at play like ancient Greeks, indulging in wrestling-bouts without harm, on sunny days. I have since, I must confess, several times observed what I believed to be this playful phenomenon, only to conclude on closer inspection, that what I was watching was not play, but war in earnest, fought, as ant-wars usually are, for limited objectives and without wholesale berserker bloodlust. Alfred Wallace, who was travelling in the same parts at that time, and is a convinced Socialist, much affected by the vision and practical success of Robert Owen’s successful experiments at New Lanark, attempted to put the problem in a kinder and milder light. Owen, he argued, had proved by his social experiments that environment can greatly modify character for the good—‘that no character is so bad that it may not be greatly improved by a really good environment acting upon it from early infancy and that Society has the power of creating such an environment’. Owen’s limited extension of individual responsibility to his workers, his care for their individual education, improved their wills, which were their individual natures. Wallace wrote (I quote an unpublished letter), ‘Heredity, through which it is now known that ancestral characteristics are continually reappearing, gives that infinite diversity of character which is the very salt of social life; by environment, including education, we can so modify and improve that character as to bring it into harmony with the possessor’s actual surroundings, and thus fit him for performing some useful and enjoyable function in the great social organisation.’

I have digressed far, you may think, from Elm Tree Bole and Osborne, the Red Fort and Stonewall City. In fact, these fundamental questions, of the influence of heredity, instinct, social identity, habit and will, arise at every moment of our study. We find parables wherever we look in Nature, and we make them more or less wisely. Religious thinkers have seen in the love of mother and infant, of Father and Son, a reflection of the eternal relations of the Prime Being with the Created World and with Man himself. My Belgian friend saw that love, on the other hand, as an instinctual response leading to the formation of societies which gave even more restricted and functional identities to their members. I have mentioned the role of Instinct as Predestination, and of Intelligence as residing in communities rather than individuals. To ask, what are the ants in their busy world, is to ask, what are we, however we may answer …

William stared at his page. He had argued round and round, not really thinking of publication, for if he had been, he thought, ruefully, at least for the large, young audience envisaged by Matty Crompton who might read for improvement, he would have had to pay more attention to the religious susceptibilities of their parents and guardians. He thought of appending that useful tag from Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.

He decided to give his pages to Miss Crompton, and gauge her response, if he could. It struck him that he knew nothing of her own religious views. A friend of Charles Darwin had once told him that almost no women were prepared to question the truths of religion. He thought, then, that the whole of what he had just written was somehow set against what Harald Alabaster was trying to say—more so than appeared on the surface of the writing, for like almost all his contemporaries, he was half afraid to give full expression, even to himself, of his very real sense that Instinct was Predestination, that he was a creature as driven, as determined, as constricted, as any flying or creeping thing. He wrote about will and reason, but they did not feel to him, in his bones, in his sense of his own weight in the mass of struggling life on earth, to be very powerful or important entities, as they were for a seventeenth-century divine under the Eye of God, or a discoverer of new stars exulting in his power. His nerve-cells pricked, his hand ached, his head was full of crawling black fog. He felt his life as a brief struggle, a scurrying along dark passages with no issue into the light.

When he gave his final musings to Miss Crompton to read, he found himself waiting anxiously for her opinion. She took the pages away one day, and brought them back the next, saying that they were exactly what was required, just such scrupulous general considerations were what would greatly increase the appeal of the book to a wide audience and lead to its discussion in all circles. She added, ‘Do you think it conceivable that there may be future generations who will be happy to believe that they are finite beings with no afterlife—or that their natures may be fully satisfied by the part they play in the life of the whole community?’

‘Such beings exist now, I believe. It is a curious outcome of travel that all beliefs come to seem more—more relative, more tenuous. I was much struck by the universal incapacity of Amazon Indians to imagine a community which did not reside on the banks of a vast river. They are not capable of asking, “Do you live near a river?” only “What is your river like? Is your river quick or slow, do you live near rapids or possible land avalanches?” They picture the Ocean as a river, I know, no matter how we may try to describe it vividly and accurately. It is like trying to tell a blind man the principles of perspective, which I once attempted. And it led me to wonder what do I not reflect upon, of what important facts am I ignorant in my picture of the world?’

‘Many—most—would not have your intellectual carefulness and humility.’

‘Do you think so? Those who will not accept Mr Darwin’s findings are divided between those who are very angry and quite sure they are right—who kick imaginary stones like Dr Johnson refuting Berkeley—and those, like Sir Harald, whose quest for assurance—reassurance—of Faith is shot through with trouble, indeed anguish.’

‘The wisdom of the serpent might suggest strengthening your case for a possible explanation that might square with Providence.’

‘Do you think I should do that?’

‘I think a man must be truthful, as far as possible, or the whole truth will never be found. You must say nothing you do not think.’

There was a silence. Matty Crompton ruffled through the pages. She said, ‘I liked your passage from Michelet about the depredations of the Sphinx Atropos. It is amazing how much—how much of mystery, of fairy glamour—is added to the creatures by the names bestowed upon them.’

‘I used to think of Linnaeus, in the forest, constantly. He bound the New World so tightly to the imagination of the Old when he named the swallowtails for the Greek and Trojan heroes, and the Heliconiae for the Muses. There I was, in lands never before entered by Englishmen, and round me fluttered Helen and Menelaus, Apollo and the Nine, Hector and Hecuba and Priam. The imagination of the scientist had colonised the untrodden jungle before I got there. There is something wonderful about naming a species. To bring a thing that is wild, and rare, and hitherto unobserved under the net of human observation and human language—and in the case of Linnaeus, with such wit, such order, such lively use of our inherited myths and tales and characters. He wished to call the Atropos the Caput mortuum, you know, the Death’s Head exactly—but the system of nomenclature requires a monosyllable.’

‘So he chose the blind Fury with the abhorred Shears. Poor innocent insect, to have its small life burdened with so large an import. I was partly struck by Sphinx Atropos because I too have been writing—and what I have been writing has become strangely involved in just these names selected by Linnaeus—I have derived much instruction both from the Systema Naturae and from the copy of Thomas Mouffet’s Theatrum Insectorum which is in Sir Harald’s library.’

‘I am amazed at your accomplishments. Latin, Greek, draughtsmanship of a high quality, a thorough knowledge of English Literature.’

‘I was educated with my betters, in the schoolroom of a Bishop. My father was the tutor and the Bishop’s lady was kindly-intentioned. I would be grateful,’ she said, seeming to hurry on past any further personal questions, ‘if you would cast your eye over this writing when you have a spare moment. I meant it for no more than an illustratory fable—you will see—I amused myself by tracing the etymology of Cerura vinula and another Sphinx, Deilephila elpenor, and thought I would write an instructive fable around these strange beasts—and found I had got rather carried away, and written something longer than I intended and perhaps, for a simple puzzle-tale, over-ambitious—and now I am puzzled what to do with it.’

‘You should publish on your own behalf—a whole volume of such tales.’

‘I did not believe I had an inventive nature. It is the chronicle of our insect cities that has stirred me up to authorship. But I do not think there is much merit in it. I count on you to be ruthlessly honest about its failings.’

‘I am sure I shall be full of admiration,’ said William, honestly, if vacantly. Matty Crompton looked thoughtfully downwards, not meeting his eye.

‘I have already said, in another context, you must say nothing you do not think.’

THINGS ARE NOT WHAT THEY SEEM

After a time they came to a smooth high wall, too high to see over, with a gate in it, which was locked. They debated a moment or two between themselves, and knocked, and the door swung open before them on smooth, oiled hinges, and swung to behind them with the same facility, although there appeared to be no one there to control it. And they heard the bolts and tumblers fall into place inside the great lock. One was for turning back, at this, and one was for scattering and hiding, but the rest—including Seth—were for continuing boldly forwards. So they walked on, across marble floors, through great cool halls, and heard splashing fountains in courtyards, and spoke in whispers of the sumptuousness of the architecture and domestic appointments.

And finally they found themselves in a banqueting hall, with a great ebony table spread with a fine feast—tasty pies and pastries, fine jellies and blancmanges, heaps of fruit with the bloom on it, and vessels full of sparkling wine. Their mouths watered so at this sight that they sat down without more ado and helped themselves, eating untidily until the juices ran out of the corners of their mouths, for they were half-starved. Only Seth did not partake, for his father had told him always to be sure never to eat anything that was not freely offered. He had been soundly beaten as a boy for trespassing in neighbouring orchards, and he was wary.

When they had been eating for some time, and were half stupid with good feeding, they heard a sound of tinkling bells and harpstrings, and a door at the far end of the hall swung open, and admitted a strange gathering of folk. There was a major-domo, who looked more like a goat than a man, and a very pretty milk-white heifer with roses wound in her horns, and a procession of herons and geese, all wearing collars studded with rubies and sapphires, and some very very pretty fluffy kittens, silver-blue and rosy-fawn, and an elegant little silver greyhound, with bells round its neck, and the loveliest King Charles spaniel, with long silky russet ears and huge, appealing brown eyes. And in the midst of these was a cheerful, comfortable-looking lady, dressed a little like a shepherdess, in a frilly cap and a delightful embroidered apron, with beautiful white ringlets falling to her shoulders. In her hand she carried the prettiest shepherd’s crook, decorated with ribbons, silver and rose and sky-blue, and she had the sweetest smile, and the most dancing eyes. All the shipwrecked mariners were immediately enchanted by her presence and began to smile fatuously amidst the grease and fruit juice on their lips and chins. It was easy to see she was no working shepherdess, but a great lady who chose to dress as one, out of condescension or simplicity of spirit.

‘How lovely’, she cried, ‘to have unexpected visitors. Eat your fill, help yourselves to wine till your cups run over. I love to have visitors.’

And the mariners thanked her, and set to again, for their hunger had been mightily restored by her words, all except Seth, who, it is true, was now invited, so was not breaking his father’s prohibition. But he still had no appetite for the feast. The delectable lady saw that he was not eating, and the goat held a chair for him, so that he was more or less obliged to sit down. And when she saw that he was not eating, the lovely lady came near with a rustling of her pretty skirts and pressed on him dishes of all manner of dainties, pouring him glasses of cordial julep and fragrant syrups, which looked like dancing flames in the crystal.

‘You must eat,’ she said, ‘or you will be faint with hunger, for I can see you have had a terrible journey, and are salt-stained and gaunt with weariness.’

Seth said he was not hungry. And the lady, without losing her smiling good temper, sliced him a salad of delicate fruits with a silver knife, and laid them out in a fan, like a flower, shavings of melon, circles of glistening orange, fragrant black grapes and crisp white apples, and slices of crimson pomegranates studded with ebony seeds.

‘I shall think you most obdurate and ill-mannered,’ said she, ‘if you will not taste even a sliver of apple, even a grape with its bloom on it, even a sip of pomegranate-juice.’

So for very shame he took up a slice of pomegranate, which seemed less substantial than the crisp apple-flesh, and ate three of the black seeds in their sweet, blood-coloured jellies.

One of the companions hiccuped and said, ‘You must be some great Fairy, ma’am, or Princess, to have all this plenty in the midst of this wilderness.’

‘Indeed I am,’ she said. ‘I am a Fairy who likes to make things pleasant for mortal men, as you see. My name is Mrs Cottitoe Pan Demos—which means, “for all the people”, you know, and that is what I am. I am for all the people. I keep open house for everyone who comes. You are all so very welcome.’

‘And can you do Magic?’ asked the ship’s Cook, who was no more than an overgrown Boy, and associated Magic with tricks and disappearances and feather dusters and bouquets appearing from nowhere.

‘Indeed I can,’ she said, with a silvery laugh.

‘Show us, show us some Magic,’ said the Cook, licking his lips.

‘Well,’ said she, ‘I can make make this feast vanish in a twinkling.’ And she touched the table with her silver crook, and all was gone, though the scent of the fruit, and the savour of the meat, and the tang of the wine still hung in the air.

‘And I can chain you in your chairs without chains,’ she said, smiling more happily, and she gave a little imperious wave of the crook, and the seamen found they could no longer rise to stand, or lift their hands from the chairs.

‘That is not very nice,’ said the Cook. ‘Let us go, ma’am. We thank you for our good meal—we must go back to mend our ship and move on.’

‘How ungrateful men are,’ said the lady. ‘They will not stay, whatever we give them, they will not rest, they will sail away. I thought you might like to stay and make part of my household, for a time. Or forever. I keep an open house for everyone who comes.’

‘No thank you kindly, ma’am,’ said the Cook. ‘I’d like to go now.’

‘I don’t think so,’ said she, and touched him on the shoulder with her silver crook, which lengthened itself for the purpose. And immediately, with a strange half-human cry, the Cook became a great hog, at least as to his head and shoulders, with a damp snout, and great tusks and bristles. Only his poor hands, clamped to his chair, were still hands, hands hard as hoofs, and hairy, and clumsy. And the lady went round the table and touched every one of the sailors, and each of them became a different kind of pig, from the great White Boar to the dapper Black and Tan, from French sanglier to Bedford Blue. Seth was interested in the variety of the pig-forms, despite his own great danger. He was the last to be struck by the crook, which sent a kind of electric shock through his whole body, stinging like a snake. He put up a hand to his head to feel his snout and was surprised to find that, unlike his fellows, he could do so. His face felt much the same, his nose, his mouth, his eyebrows. But there was a kind of itching and rushing in his head, and he felt upwards and there was his hair, springing outwards like water from a fountain, into a kind of prancing mane.

Mrs Cottitoe Pan Demos laughed heartily at this sight.

‘I never can tell what the effect of my magic will be on those who eat only frugally,’ she said. ‘Your head of hair is very handsome, I think, much more handsome than tusks and bristles. But you must still make one of our party, you know. I shall set you to work as my swineherd—my swine are kept deep in the rocky caverns below this palace, for pigs have no need of daylight, and I shall show you how to arrange their fodder, and clean out their sties, and I am very much afraid you will be horribly punished if you do not do it well. For we must all co-operate, you know, for the good of the household. Come with me, my dear.’

And she drove all the creatures—the new swine and the geese and the herons, the little heifer and the old goat—at a spanking trot through the corridors, laughing musically when they slid about on their awkward hoofs, waving her pretty crook, which stung mercilessly wherever it touched hide or fur. And under the palace they found an enormous succession of pens, caverns and cages, in which languished all sorts of creatures, docile rabbits, gentle palpitating hares, drooping draggle-tailed peacocks, a few donkeys, a few Barbary ducks, even a nest of white mice.