Shortly after daybreak, and heralded by a thick succession of fiercely shaken thunderbolts, the solidity of the whole earth was made to shake and shudder, and the sea was driven away, its waves were rolled back, and it disappeared, so that the abyss of the depths was uncovered and many-shaped varieties of sea creatures were seen stuck in the slime … Many ships, then, were stranded as if on dry land, and people wandered at will about the paltry remains of the waters to collect fish … Then the roaring sea, as if insulted by its repulse, rises back in turn, and through the teeming shoals dashed itself violently on islands and extensive tracts of the mainland, and flattened innumerable buildings in towns or wherever they were found.1

The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus’s dramatic account of the great earthquake that struck Alexandria on July 21, 365 C.E., understates the extent of the catastrophe. Thousands drowned; ships ended up on house roofs, some cast so far inland that they rotted where they lay. The disaster was so traumatic that Alexandrines commemorated the anniversary for two centuries.

Alexander the Great had founded what was then a small town on the western Nile delta coast in 331 B.C.E. Alexandria, named after the great conqueror, soon became one of the busiest ports of classical antiquity. The cosmopolitan city, with its more than three hundred thousand inhabitants, was a hub of commercial activity, a great center of learning famous throughout the Mediterranean world. Today, almost nothing remains of the harbor of two thousand years ago, which lies below sea level, the victim of natural subsidence.

Until recently, all we knew about the port came from descriptions by Strabo and other classical authors, and maps based on their writings over a century ago. Businessman turned archaeologist Franck Goddio has used electronic surveys of the now-sunken harbor to reconstruct the great harbor, with its breakwaters and famed lighthouse, the Pharos of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.2 It is said to have been 140 meters high, a square tower with an iron fire basket and a statue of Zeus the Savior. An elaborate complex of palaces, temples, and smaller harbors lay within or close to the port. Subsidence in the order of five to seven meters since antiquity has effectively buried the port. Thousands of exploratory dives have yielded dozens of finds buried in the shallow water, many recovered with their exact positions marked by GPS, others, like the remains of a thirty-meter ship of the first century B.C.E., still left in place. Smaller artifacts include numerous magnificent artworks, well-preserved columns in pink granite from Aswan in distant Upper Egypt, and the remains of a palace said to be associated with Queen Cleopatra.

The Roman coastline has long vanished underwater. Six and a half kilometers offshore lie the remains of Heraklion, another port founded by Alexander, doomed by a combination of subsidence, earth movements, and shoreline collapse. Heraklion, the ancient Egyptian Thonis, lay on a peninsula between several port basins to the east and a lake extending to the west. The city with its bustling port controlled access to the now-vanished Canopic branch of the Nile. According to Herodotus, Heraklion was the mandatory port of entry for all ships arriving from “the Greek Sea.”3 Goddio and his colleagues have located an imposing temple to the sun god Amun, and also more than seven hundred anchors and twenty-seven wrecks dating to between the sixth and second centuries B.C.E. A large channel once passed through the city, linking the port to the lake and the river. The now-vanished port, finally destroyed by an earthquake during the eighth century C.E., was a gateway to Egypt for many centuries before Alexandria rose to prominence.

The fertile soils of the delta with its lagoons, marshes, and wetlands extended inland from Alexandria. They were a granary and the source of ancient Egypt’s wines. Delta vintners nurtured fine wines, which enjoyed a gourmet reputation. The third-century Greek author Athenaeus, from the delta city of Naukratis, loved the wines from Mariut, southwest of Alexandria: “excellent, white, pleasant, fragrant, easily assimilated, thin, not likely to go to the head, and diuretic.”4

RED WINE: the blood of Osiris, the god of resurrection. An early pharaoh, Scorpion I, went to eternity in 3150 B.C.E. at Abydos in Upper Egypt.5 Three rooms of his sepulcher were veritable wine cellars, stacked with over seven hundred wine jars containing nearly forty-five hundred liters of fine vintages imported from the Levantine coast and from vineyards inland. Several centuries later, the pharaohs established their own royal winemaking industry to satisfy their desire for wines, often laced with figs. An Old Kingdom pyramid text tells us that deceased pharaohs dined off figs and wine, which it called the garden of the god. Such meals nourished the pharaoh in eternity.

Most royal vineyards were in the delta, begun with imported grapevines. The first vintners were foreigners. Even in later centuries, many were Canaanites, who brought sophisticated methods to the business from the beginning. The blistering heat of the delta required irrigation for water-sensitive grapes, but fortunately the soil was rich alluvium, nourished by the Nile flood and salt-free. Millions of amphorae of red and white wine from delta vineyards supplied pharaohs and temples over the centuries and provided drink offerings at major religious ceremonies. Tomb paintings show workers stomping the vintage, holding on to vines to maintain their balance. In 1323 B.C.E., mourning officials provided the young pharaoh Tutankhamun with amphorae of fine red and white wines labeled with the location and the names of the vintners, most of them from the western delta.6 The reputation, and acreage, of delta wines survived into Islamic times.

Fertile soils nourished with silt and floodwater, flushed of any trace of rising salinity by the inundation: Ta-Mehu (the ancient Egypt name for the delta) was a patchwork of vineyards and productive cereal agriculture from very early times. The delta was Egypt’s exposed northern flank, subject to inundation and to incursions from the sea, in human terms a permeable northern frontier, sometimes fortified and used as a military base for strong rulers, at others occupied by invaders from what is now Libya or from the Levant. Ta-Mehu linked the pharaohs with the ocean and the wider world beyond the horizon.

The pharaohs’ greatest wealth was from agriculture, from the crops grown using the ideal natural cycle of the great river, much of the harvest coming from the delta. For more than three thousand years, the life-giving waters of the Nile defined ancient Egyptian life from the First Cataract to the Mediterranean. The river was an artery for transport and communication, the source of agricultural bounty, and it supported rich fisheries. Hardly surprisingly, the pharaohs developed a complex ideology that centered on the river and its annual inundation. Creation myths spoke of the waters of Nun, which receded to reveal a primordial mound, just like the floodplain emerging from the retreating inundation. The creator god Atum appeared at the same moment and sat on the emerging tumulus. It was he who was the first living being, who created order from chaos—just like every pharaoh who presided over the Two Lands.

In Ta-Mehu, as elsewhere in Egypt, three seasons defined the year: Akhet, the inundation, Peret, growing, and Shemu, drought.7 The natural cycle of the Nile governed all attempts to cultivate the delta. Akhet provided life-giving water and silt, although human ingenuity could do much to improve the watering of the land. Farmers raised earthen banks to enclose large flood basins where they could retain water before releasing it. This was irrigation at its simplest, but it was usually sufficient to feed the four million to five million Egyptians who lived along the river at the height of the pharaohs’ power during the second millennium B.C.E. There was no talk of cash crops in a self-sufficient agricultural economy. Such a notion was unthinkable to the pharaohs and their subjects. A small army of officials and scribes oversaw agriculture throughout the kingdom, but their interest was not in the nuances of farming, but purely in carefully documented yields for rents and taxes. For many centuries, ancient Egyptian villages fed the kingdom.

Farmers living in the delta may have labored in royal or temple estates as well as in village fields. There was generally enough to eat, crop yields were usually, but not invariably, more than adequate, and there was slow population growth with little or no threat from rising sea levels. Barrier dunes, extensive lagoons and marshes, and thick mangrove swamps served as natural fortifications for the farming landscape farther inland during thousands of years of very minor sea level change—most of that which did occur resulted from subsidence caused by earth movements.

WE SHOULD EMBARK on a minor environmental tangent here, for wetlands and marshes are important players in coastal protection in many parts of the world.8 Wetlands are part of both aquatic and terrestrial environments. They are most widespread along low-lying coasts, such as those of the Florida Everglades, the Mississippi delta, or the delta shores of Bangladesh in South Asia. Like wetlands, freshwater and salt marshes are highly productive and often biologically diverse. Both provide invaluable protection against coastal erosion as well as providing excellent habitats for birds, fish, shrimp, and other organisms.

Salt marshes, flooded each high tide, have less biological diversity, for few plants can tolerate saltwater. They also trap pollutants flowing toward the shore from upstream and provide nutrients to surrounding waters. Being constantly inundated by rising tides, they are well adapted to rising sea levels. In the natural course of events, the marsh surface rises each year through the natural accumulation of sediments. At the same time, they also creep inland as sea level rises, maintaining themselves as the landscape changes, just as barrier islands do. Thus, they offer excellent natural coastal protection where the topography permits inland creep, provided agriculture and building do not destroy them, as now happens increasingly all over the world. Modern-day seawalls and other coastal defenses limit marsh expansion in estuaries, a chronic occurrence along the East Coast of the United States with its proliferation of coastal vacation properties. The destruction and especially restriction of inland expansion of marshes and wetlands have deprived us of vital coastal protection.

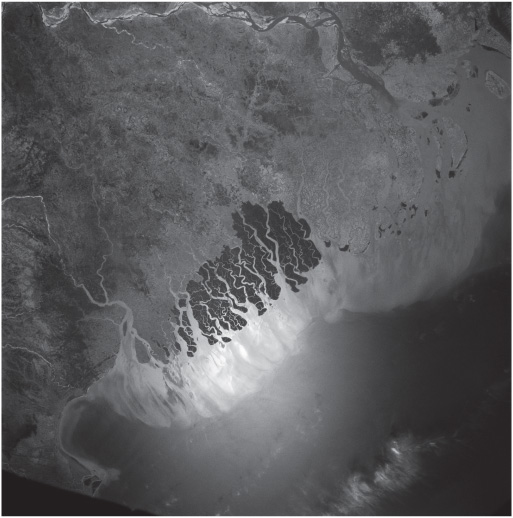

Figure 7.1 Sundarban mangrove swamps (dark areas) lie at the mouth of the Ganges River in Bangladesh. Taken from the space shuttle Columbia on March 9, 1994. Courtesy: NASA.

Mangroves protect coastlines over an enormous swath of the tropical world, including the Nile delta, in areas where waves are low and often where coral reefs protect them. Dense belts of them offer superb coastal protection, as the inhabitants of Homestead, Florida, discovered in 1992, when Hurricane Andrew’s waves harmlessly surged into mangroves that protected the town. Mangroves also saved the Ranong area of Thailand from the great tsunami of 2004, which killed numerous victims in neighboring areas where the mangroves had been cleared (see chapter 10). Brazil is home to 15 percent of all mangrove habitats, but they line between 60 and 70 percent of tropical coastlines, or did until the twentieth century. Different mangrove species inhabit the diverse zones of coastal habitats, each growing at the limits of its tolerance for salinity. As the oceans warm, we can expect mangrove swamps to expand northward and southward from their present ranges, which is good news, for they nurture numerous species of birds, fish, reptiles, and shellfish. In Bangladesh, they were home to tigers. In Brazil and Colombia jaguars hunt prey at the edge of mangrove swamps.

For all their usefulness, mangrove thickets deter people with their tangled vegetation, numerous snakes, and endemic mosquitoes. They have inevitably become a target for destruction, cleared for agriculture and aquaculture, used as a source for house timber, a centuries-old industry in East Africa, whose swamps provided wood for houses in treeless Arabia. Today, the greatest threat to mangrove swamps comes from aquaculture, especially shrimp farming, which is a huge international industry in poverty-stricken countries like Bangladesh, Ecuador, and Honduras. Fortunately, mangroves are in no danger of extinction, for they are capable of adjusting effortlessly to sea level changes. Their greatest threat comes from humanity. We seem unaware that mangroves, marshes, and wetlands are some of our best weapons against onslaughts from the ocean.

BACK TO THE NILE: During the first millennium C.E., the delta rose to political and economic prominence, thanks to its burgeoning links with Greece, Rome, and other easily accessible, powerful kingdoms beyond Egypt’s boundaries. The political equation changed decisively with the founding of Alexandria on the delta coast in 331 B.C.E., which brought the entire Mediterranean world to Egypt’s doorstep. Much of the prosperity stayed downstream at a time when the diverse mouths of the Nile shifted and shifted again as a result of earthquake activity, subsidence, and coastal erosion. As was always the case until camel caravans became commonplace, most trade into the Nile valley traveled up the river. The delta beyond its growing cities and ports still remained somewhat of an agricultural backwater, despite its rich soils and excellent taxation potential, for there was negligible population pressure by modern standards. An estimated three hundred thousand people lived in Alexandria at the time of Christ, some half a million in Cairo a thousand years later, a medieval city that, thanks to Mamluk rulers, became a prosperous camel caravan meeting place after the thirteenth century and soon overshadowed the coastal city.

There was still plenty of cultivable and taxable land in the delta after Cairo rose to prominence. Repeated plague epidemics kept population growth in check, so it was still easy to adjust to sea level changes and coastal subsidence. Today the delta is so densely populated that there is not enough land to go around and the ocean is moving inland. Compare the medieval figures of 300,000 and 500,000 people with those for 2011: Over 3.8 million people crowd into modern Alexandria, while Cairo with its over 6 million urban inhabitants has a staggering population density of 17,190 people per square kilometer, one of the most densely populated cities in the world, this before one factors in the surrounding suburbs. The soaring urban and rural populations of both the delta and Upper Egypt have brought the complex relationship between the Nile and the ocean to the brink of crisis.

The present delta crisis has its origins in the early nineteenth century, when the Mamluk Muhammad Ali Pasha, well aware of the economic potential of Lower Egypt’s soils, decided to increase cotton production in the delta, cotton being a lucrative cash crop. Ali deployed forced labor from villages along the Nile in an orgy of deep canal digging.9 His ruthless practices and the ambitious, often unsuccessful projects of his successors resulted in massive international debts and a breakdown of political order that led to British occupation in 1882. The new occupiers in turn invested heavily in irrigation agriculture both as a way of paying off foreign creditors and to feed a burgeoning population, over seven million in 1882 and up to eleven million by 1907. Even with these investments, there was insufficient inundation water to go around. The British consul general, Lord Cromer, laid plans for a network of dams and barrages to expand irrigation and to reduce dependency on unpredictable floodwaters.

His timing was impeccable politically. By this time, epic Victorian explorations had traced the Nile to its multiple sources. Furthermore, the British controlled the entire length of the river except the upper reaches in Ethiopia, so long-term planning and major dams were practicable for the first time. The so-called Aswan Low Dam was constructed immediately below the First Cataract between 1898 and 1907, with numerous gates to allow both water and silt to pass through.10 The dam was too low, so it was raised twice, in 1907–1912 and again in 1929–1933, giving it a crest thirty-six meters above the original riverbed. Even that was not enough. After the inundation nearly topped the dam in 1946, the British decided to build a second dam about seven kilometers upstream. Changing political circumstances and international maneuvering delayed construction until 1960–1976. The massive rock-and-clay Aswan Dam, 111 meters tall and nearly 4 kilometers from bank to bank, truly blocked the river, forming Lake Nasser, a huge reservoir 550 kilometers long.11 Spillways allow a constant flow of water through the barrier, so the Nile is no longer a natural watercourse but effectively a huge irrigation channel. Instead of overflowing its banks, the river remains at the same level year-round.

The Aswan Dam protects Egypt from floods and the immediate effects of drought, but the long-term environmental consequences are only now beginning to come into focus. In predam days, when the Nile flooded, the low groundwater level when evaporation was highest in summer prevented salt rising to the surface through capillary action. Now the groundwater level is higher and more constant natural flushing has virtually ceased. As a result, soil salinity has increased dramatically, endangering agricultural yields. Only now are large-scale, and extremely expensive, drainage schemes attempting to take care of the problem. Before the Aswan Dam, 88 percent of the silt carried downstream ended up in the delta. Now 98 percent of the silt load remains above the dam and virtually no silt reaches the ocean. Chemical fertilizers have replaced silt; diesel pumps rather than gravity provide irrigation water year-round. Some years the authorities close off the dam for two or three weeks in winter. Far downstream, the surviving delta lake levels fall rapidly; sea-water promptly enters them.

Figure 7.2 Constructing the first Aswan Dam around 1899. D. S. George/British Library.

Even the construction of the Aswan Low Dam affected the distant coastline, for reduced silt levels removed some of the natural barriers to coastal erosion. The High Dam has had much more widespread effects that may even be felt far from the delta, elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean.12 Groin and breakwater construction to refresh beach sand along popular beaches has had some beneficial results, but the long-term effects are impossible to discern. There are other problems as well. With many fewer nutrients carried to the coast, both lagoon and in shore marine fisheries are fading rapidly. Sardines off the delta depended heavily on phytoplankton during the flood season. Absent the inundation, the Egyptian sardine fishery declined from about eighteen thousand tons in 1960 to around six hundred tons in 1969, even less today. Stocks have now recovered considerably, largely because of winter outflows from coastal lakes, but there are signs that sardine migration patterns have changed. Water hyacinths are clogging waterways and canals, increasing water loss through evaporation and transpiration (loss of water vapor from plants).

Quite apart from the ecological damage, escalating demands for water for industrial, urban, and agricultural purposes upstream of the delta mean that less and less of the Nile reaches the northern reaches behind the shoreline. Much of what does is polluted by industrial waste, municipal wastewater, and runoff from fields treated with heavy doses of chemical fertilizer. The polluted water flows into already shrinking coastal lagoons, threatening fisheries and waterfowl habitats.

All this is before one factors in population growth and inexorable sea level rises associated with global warming. Egypt’s population is expected to exceed a hundred million people by 2025. Sea levels will rise by at least a millimeter a year into the foreseeable future without accounting for projected climate changes. Combine these sea level figures with estimates of the effects of natural land subsidence, commonplace, as we have seen, in the eastern Mediterranean, and the forecasts are even more depressing. Sophisticated computer models project a relative rise of sea level of between about 12.5 centimeters to an extreme of 30 centimeters in the northeastern delta. These are by no means vast rises in vertical terms, but they are potentially catastrophic horizontally across the northern delta, where the relief varies by little more than a meter. An estimated two hundred square kilometers of agricultural land will vanish under the ocean by 2025, at a time when the rural population density of the delta is rising rapidly.

At present, the Mediterranean is winning the long standoff between land and sea. More sediment now leaves the delta than arrives there. As a result, the ocean will cut back the shore vigorously, even at points of resistance like promontories. Sand washed ashore by storms will infill coastal lagoons. Constantly shifting dunes will form in many places, which will be hard to stabilize by any form of artificial protection. Coastal sand barriers will migrate inland, filling the remaining coastal lagoons, which are already subdivided by expanded irrigation work, roads, and other modern industrial infrastructure. As marshes and swamps disappear, already decimated reserves for migrating birds and waterfowl will vanish. By 2025, inexorable pumping will encourage the inland migration of saltwater-laden groundwater at a time when more and more land is being diverted from agriculture to urban and industrial use.

Figure 7.3 The Nile River valley and delta from space, an image taken on September 13, 2008, with MODIS, NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer aboard the Aqua satellite. Courtesy: NASA.

The delta has ceased to function as a balanced system. What can be done to solve these daunting problems of land shortage, groundwater pollution, and environmental degradation resulting from an exploding population and increasingly scarce water supplies? In many respects, the Nile delta is akin to the Netherlands, a land trapped between a rising ocean and the land. Egypt does not have the financial resources to embark on a massive coast protection project like those along the North Sea. Nor are there the funds to construct the artificial wetlands and treatment facilities for recycling wastewater—or regenerating mangrove swamps to protect the coast. To restrict and control the increasingly limited waters of the Nile will require strong political will, and also an infrastructure and mechanisms for ensuring fair shares for all, from individuals to industry and agriculture. The stakes are literally life and death. One estimate has it that food shortages resulting from environmental degradation and rising sea levels will trigger massive famines that could turn more than seven million people in Egypt into climate refugees by the end of the twenty-first century–and that figure is conservative. Herodotus was right when he wrote that the Egyptians would suffer if the Nile flood dried up, for drying up it is just as sea levels rise inexorably.