Americans have had a long-standing reputation for being meat eaters. But concern about fat intake and more specifically, saturated fat, coupled with meat’s relatively high cost, got people to cut back, or even eliminate meat from their diets entirely. While cutting back is not a bad idea, meat remains an excellent source of high-quality protein. And, if you make smart choices and eat meat in moderation, you can keep within your budget and enjoy a healthy diet.

Buying Meats

Shop for meat the way you would for produce, grains, or any other product. Pick a market that has a high turnover and where you know you’ll be getting the freshest product. Specialty meat markets, farmer’s markets, co-ops, and some supermarkets have butchers on hand. By asking questions, you can learn a great deal about the right cut to buy for your specific purpose.

If you shop where the meat is prepackaged, carefully examine the package and label. See-through trays that permit you to inspect both sides of the meat are ideal. The label should provide the name of the type of meat, the cut (chuck, round, shank, loin), the specific retail name of the cut (steak, rib roast, chop), the price per pound, and the sell-by date.

OTHER LABEL CLAIMS

Organic/certified organic: To put “Organic” or “Certified Organic” on a label, farmers must receive certification from a third-party certifier approved by the USDA through its National Organic Program (NOP). To qualify, the animals must be fed a diet of 100 percent organic feed, with no antibiotics, no growth hormones, and no animal by-products. The animals must be raised free of (most) fertilizers, genetic engineering, radiation, sewage sludge, and artificial ingredients. The animals must also have access to the outdoors (though this is often overlooked or very liberally interpreted); see “Certified humane,” below.

Raised without antibiotics: There is no third-party certification for this claim.

No Chemicals added: A meaningless claim, unsupported by government oversight and not even officially defined.

No additives: The government defines additive as something that provides a “technical effect” in food (e.g., coloring, flavoring, or preservatives). There is no third-party certification, and because the terms of the label are vague, an animal might have been fed hormones but the producer could still apply this label.

Grass fed: Cattle fed on grass produce meat with higher levels of omega-3s and lower levels of saturated fat (though it’s not clear just how much grass in the diet produces this effect). The USDA has established a standard for grass-fed labeling that states only cattle that have a diet solely from grass and hay and no grain or grain products can be labeled grass-fed.

Certified humane/free farmed: These are trademarked stamps from third-party companies, each with its own very strict set of standards and verifications. Both require the animals to be raised in an environment that includes, among other things, proper protection from weather, adequate space to move around, and care by “humane-trained” handlers. These label terms do not imply anything about organic feed, hormones, or antibiotics.

Natural: Legally this means that the product contains nothing artificial. It has nothing to do with the animal’s diet, hormones, antibiotics, or living conditions.

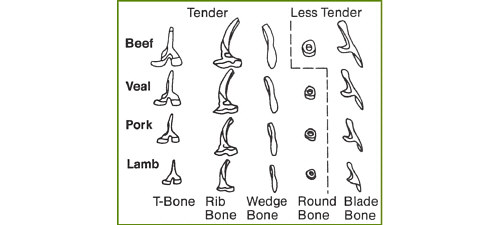

Something to keep in mind while shopping for meat is that the shape of the bone is usually a good guide to the tenderness of the piece (see illustration below).

When choosing fresh meats, look for these qualities:

Beef: A uniform, bright, cherry-red color is characteristic of good beef. Lean meat is firm with a fine texture and little marbling (distribution of fat particles throughout the lean), while fattier cuts are well marbled. Red, porous bones also indicate good-quality beef. The fat should be white.

Lamb: Young lamb should be pink to light red in color, firm, and fine textured with slender, porous bones. The meat of older lamb is light to deep red, and the bones are drier than that of younger lamb. The external fat on both should be firm.

Pork, fresh: Good-quality fresh pork has a high proportion of lean to fat and bone. The lean is firm, fine textured, and grayish pink to light red in color. Leaner cuts, such as pork tenderloin and center-cut loin, have exterior fat but little interior fat; fattier cuts such as pork shoulder are well marbled.

Pork, cured: A deep pink color is typical of the meat of cured pork. Sodium nitrate and sodium nitrite are commonly used in curing pork (as well as beef). While several decades ago there was great concern about these curing agents causing cancer, today the National Academy of Sciences, the American Cancer Society, and the National Research Council agree there is no cancer risk associated with the consumption of cured meats. The Food and Drug Administration and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) agree, providing the amount is at regulated levels. In fact, the cured meat industry is using these preservatives in less than the amounts allowed by the government. That said, there are now many more nitrate- and nitrite-free choices available.

Veal: The meat of very young veal is pale pink to grayish pink; that of somewhat older veal is slightly red. All veal should have a smooth texture with practically no marbling.

BUYING GROUND MEAT

Although ground beef is the most common and popular of the ground meats, lamb, veal, and pork are also available in ground form. Often a combination of ground pork, veal, and beef will be sold as “meat loaf mix.” As you buy ground meats, notice whether the meat is liberally specked with white. Fatty ground meats show a great deal of white throughout, causing the overall color to be light pink. By comparison, the white is less noticeable in lean ground meats, so they look fairly dark and red. Many markets will mark the fat or lean percentage on the label, often choosing the lean percentage because it’s more impressive (i.e., 93 percent lean, rather than 7 percent fat).

Here’s what ground beef labels mean, by law:

- Ground hamburger: any cut of beef (though generally from less-tender cuts) and can have fat added, but not more than 30 percent fat by weight

- Ground beef: any cut of beef but cannot have any added fat and must have no more than 30 percent fat by weight

- Lean ground beef: must have no more than 22 percent fat

- Extra-lean ground beef: has no more than 15 percent fat; often as low as 7 percent fat (93 percent lean)

BUYING VARIETY MEATS

Variety meats include the liver, heart, kidneys, tongue, brains, sweetbreads (thymus gland), and tripe (stomach lining). Consumed regularly in other parts of the world, these meats have never been very popular in this country. Although they are usually economically priced and rich in nutrients, there are other concerns to be aware of. For example, the function of the liver is to filter out toxins in the body, so if you are buying liver from an animal that hasn’t been raised organically, you may be consuming unwanted substances. And certain organs are fairly high in cholesterol—sweetbreads, for example, have 250 milligrams of cholesterol in a 3-ounce serving. By comparison a 3-ounce portion of sirloin steak has 57 milligrams. We’ve narrowed the field here to the cuts we think most people might try.

Beef or calf’s liver: Beef liver will be a deep red-brown color. Calf’s liver, the more popular of the two, is pale and grayish pink in color. Calf’s liver tends to be sweeter than beef liver. Both will be sold in slices. If the skin is still on, remove it with your fingers.

Tongue: Tongue is firm, with a rough skin covering. Beef and veal tongue are available pickled, corned, smoked, and fresh. Pork and lamb tongue are often sold cooked and ready to serve, but can also be found fresh.

Tripe: Plain (or smooth), tripe is the tissue lining of the first stomach of beef or veal; honeycomb tripe comes from the second stomach. Tripe is available fresh, pickled, and canned. Although fresh tripe is actually partially cooked when sold, it must still be cooked for a couple more hours before it is edible.

Oxtail: Weighing under 2 pounds, fresh oxtail has a rosy appearance and is more often than not sold already cut into pieces. It is often sold frozen.

BUYING SAUSAGE

Sausage varieties can be divided into two broad categories: 1) uncooked, which includes fresh, cured, smoked, and air-dried sausage, and 2) fully cooked and ready to serve, which only needs to be heated if it’s for a hot dish.

Commercially made sausage is seldom merely fresh meat and seasonings stuffed into natural animal casings (pork, lamb, or beef intestines). It can also contain fillers, additives to retard spoilage, and preservatives. Be a smart consumer, check the label, and choose the packages with the least amount of ingredients beyond the meat and seasonings.

As with other meats, choose the freshest sausage that you can. Quality deteriorates in all sausage during storage, even if it has been smoked and dried. Look at the links or patties. The fat (tasty sausage is about one-third fat) should be evenly distributed throughout, and the links should be unbroken and lightly packed. Broken or overstuffed sausage will split during cooking. Check the label to see whether the sausage is fully cooked or if it must be cooked before serving. Examine the exposed surfaces and avoid those that are slimy or have any liquid present.

For the freshest sausage, try making it yourself (see page 32).

Inspection & Grading

Before and after slaughter, all meat must be federally inspected for wholesomeness. (Some states have their own equivalent inspection for meat sold within the state.) Those meats passing the inspection have a round, purple mark to indicate that the meat came from a healthy animal and that it was processed under sanitary conditions. The stamp is put only on carcasses and major cuts, so it will rarely appear on small retail cuts. If the stamp does appear on a piece of meat, don’t bother trimming off the blue marking—it is harmless, as it is made with a food-grade dye.

For a fee, the USDA offers grading of beef, lamb, and veal as an optional service to packers. The grade marking, a shield-shaped stamp, is a guide to quality—tenderness, juiciness, marbling, and flavor—in meat. U.S Prime has the most marbling and is the most tender, but rarely makes it to the market; rather most of it is sold to restaurants (and some high-end butchers). U.S. Choice is the most widely available, with less marbling than Prime. U.S. Select is the leanest and least tender of the three.

Spending Wisely

When selecting from the many cuts of meat available, always try to figure the cost per serving. A cut with a high price per pound and with little waste is often more economical than one that is less expensive but has lots of waste. Of course, the actual number of servings in a pound depends on individual appetites.

Storing & Thawing Meat

All fresh and cooked meats are perishable. Store fresh meats, loosely covered with waxed paper or foil, in the coldest part of your refrigerator. While some fresh meat will keep for 5 to 7 days, most are best if used within 1 to 3 days. (See “Home Storage of Meat,” opposite.) Cover cooked meats and meat dishes and keep them in the refrigerator for no more than 4 days. Always store gravy, stuffing, and meat in separate containers. For longer storage, freeze fresh and cooked meats as well as meat dishes, gravies, and stuffings (see “Freezing Meats,” page 627, and “Freezing Prepared Foods,” page 628).

To maintain safety and high quality, thaw fresh and cooked meats, still wrapped, in the refrigerator. For a quicker method you can immerse a package of raw meat in its watertight wrapper in cold water. Change the water every 30 minutes. Thaw until pliable. Meat that is cold enough to retain ice crystals may be safely refrozen, but quality will suffer.

If, at any time, the meat has an off-odor, a slimy surface, or mold, throw it away.

HOME STORAGE OF MEAT

MAKING FRESH SAUSAGE

Making your own seasoned sausage is fun and easy. And you know the ingredients are natural, fresh, and wholesome. Basically, fresh, homemade sausage contains meat, fat, and seasonings. Vegetables, grains, and dry milk solids may be added to increase nutrients as well as to change texture and flavor.

While pork is most commonly used to make sausage, beef and poultry are also good. Fat is a necessary ingredient; it adds flavor, binds the meat and the seasonings, and lubricates the casings. As a rule, one part fat to two parts meat makes a moist, juicy sausage. Pork fat is the most common type used.

Sausage Making Equipment

The only equipment needed for making sausage is a meat grinder, a sharp knife, and, if you are making links, a funnel or a stuffing attachment for the meat grinder. For links you will also need to make your own cloth casings or purchase animal casings.

Sausage Casings

Casings made from pork, lamb, or beef intestines, as well as those made from cheesecloth or muslin, help sausages retain their shape during cooking. Pork or lamb casings are a good size for small sausages and beef casings work well for larger sausages.

Animal casings can be purchased fresh or packed in salt. They are available from some butchers or meat wholesalers.

For most recipes, you'll need about 4 feet of 1-inch-diameter pork or lamb casings for every 3 pounds of sausage; 1 foot of 1½-inch-diameter pork or lamb casings for each pound of sausage; or 2 feet of 3- to 4-inch-diameter beef casings for every 5 pounds of sausage. Buy more than you think you’ll need, as casings tear easily.

Preparing animal casings for use: If originally packed in salt, first soak them in lukewarm water for about 30 minutes, changing the water two or three times. Rinse under running water; then open and run cold water through the inside several times. Remove the inner membrane. Fill casings and tie off lengths with string. Store unused casings, packed in salt, in a sealed plastic bag in the refrigerator or freezer. They will keep this way indefinitely.

Making a cloth casing: Cut cheesecloth or muslin into a long, narrow rectangle (15 × 6 inches). Dip the cloth into cold water; then wring out excess water and spread the cloth on a flat surface. Spoon sausage meat lengthwise down the center of the rectangle and fold the cloth over the meat. Roll to form a long, regular shape. Use string to tie the ends shut.

How to Make Sausage

Grind meat and fat in a meat grinder or finely chop with a knife. Blend the meat mixture and seasonings together in a bowl. Next, shape patties and loaves by hand, or fill casings using a funnel and the long handle of a wooden spoon, or the stuffing nozzle on the meat grinder. Do not overfill since overly plump casings tend to burst during filling or cooking. Break air bubbles with a pin; then twist or tie sausage to desired lengths.

Fresh sausage may be stored in the refrigerator up to 3 days. For longer storage, freeze—but it is best not to keep longer than 6 weeks. The high fat content in sausage encourages rancidity.