In our practice we concentrate on the body, the breath, and the mind. Our senses are included as part of the mind. Although it theoretically appears possible for body, breath, and mind to work independent of one another, the purpose of yoga is to unify their actions.

—Desikachar, 1995

• Discover why adding bodywork to therapy is so helpful

• Transform everyday postures—standing, sitting and lying prone—into yoga asanas

• Perform simple yoga asanas to engage the body right in the therapy office as part of the session or at home between sessions

• Train in specific yoga postures, unifying mind, brain, and body to bring about emotional change

Everything we do in life involves taking one of three fundamental postures: standing, sitting, or lying prone. As we hold and move through those postures, we take part in our world.

Yoga asanas are always based on one of these fundamental postures, with many creative combinations and variations; however, one important quality of yoga asanas makes them different from the postures you use in everyday life: unified awareness. Typically, you probably pay little attention to how your body is positioned unless it becomes a problem for you. But when practicing yoga postures, you deliberately place your body into a position, hold it, bring your attention to it, and synchronize your breathing with it.

Holding your body in position in this way has many specific and nonspecific therapeutic benefits. Even though therapy typically transpires in the sitting posture and/or sometimes from a lying prone position, you can extend the therapeutic effect of bodywork by working with different yoga postures.

A graduate student was working on his PhD in mathematics. He told us that he liked his adviser, the university, and his area of study. And yet, he felt anxious, and his anxiety was becoming worse. When he sat down to study, his anxiety levels increased. He told us that his friends called him Mr. Spock because he tended to be logical. He wasn’t too sure about psychotherapy but felt desperate enough to try anything. True to his nickname, he said, “I’m coming to see you because meditation seems like the logical thing to do.” He was factual in the account of his life and his concerns, with no reference to feelings except for anxiety. He told us he didn’t have time to exercise, nor had he ever liked it much. In fact, he hardly moved as he spoke.

We began his meditation training by teaching him to attend to simple, everyday postures: standing, sitting, and lying prone. He found that having something definite to focus on was helpful. We encouraged him to notice his body sensations in each position, such as body temperature, heartbeat, and body alignment from head to toe. He focused on his breathing and learned to relax his breath. In time, he began to notice that he was holding his body rigidly and felt interested in learning some yoga stretches. We taught him the triangle pose and sun salutation, which he could practice intermittently during the long hours he spent at his lab. Gradually he felt more comfortable physically and his anxiety lessened. We also talked about finding a better balance for his life, which included his body and his emotions in attunement with his mind. Interestingly, he told us at his closing session that he now felt some of the mathematical insights that he was working into his dissertation as body sensations. He believed his intellectual work was enriched by his meditative practice.

The following list includes a number of important benefits to integrating yoga postures into therapy.

1. Unify mind, body, and breath. Often when people are suffering from stress, trauma, anxiety, depression, and addiction, they have been out of touch with their physical responses, dissociated from the broad range of possible experiences, and instead remain narrowly focused on the discomforts. Linking mind with body through mindful awareness of body postures and gentle breathing can lessen your feelings of distress by rebalancing nervous system reactions. At the same time, your attention becomes free to perceive more clearly and fully.

2. Work on problems indirectly through the body. Your psychological disturbances are also expressed in your body, and so working on the body level provides a new doorway to change. Body sensing can loosen old patterns and form healthier ones. New feelings emerge naturally and automatically. When you take on a new posture, you might find yourself feeling more self-confident, competent, and calm. Such feelings occur bottom-up as a direct response, setting in motion a process of inner development and integration.

3. Bring about balance and stay centered. Therapy helps people find balance. Talking therapies bring this about through better thinking and improved emotional regulation, but you can influence balance directly through bodywork. People often neglect their posture, a key element of balance, and find themselves burdened with aches, pains, and fatigue. Postural aberrations force you to fight against gravity, thereby dissipating your energy. When you are able to center your body as you go through your day, gravity becomes your ally, and body positioning during action becomes effortless. Yoga poses are designed to bring about general body balance, and in the process, foster emotional balance as well. Through balancing your body, you can find your center. This centered feeling can become a resource for self-regulation, a comforting zero-point to return to when you are feeling disturbed.

As you perform a yoga posture, first on one side and then on the other, you may notice that each side of your body is different. Most people find that positions are easier on one side than the other. In fact, people often favor one side over the other. Yoga works on both sides equally, helping to strengthen the weaker side. By using both sides of your body, the two hemispheres of your brain are stimulated. Eventually, mind, brain, and body become integrated, working together for optimal functioning.

4. Produce a dual effect of alertness with relaxation. The practice of yoga postures has a dual effect, shared by many meditation methods, of alertness combined with relaxation. Often when we are trying to accomplish something, we are alert but we are also tense. Meditation teaches how to be alert while being relaxed. Relaxed alertness can help to reduce stress because it increases a person’s ability to handle challenges. Patañjali’s Yoga Sutra described these two qualities as the key to performing yoga postures: sthira (alertness) and sukha (relaxation). “These qualities can be achieved by recognizing and observing the reactions of the body and the breath to the various postures that comprise asana practice. Once known, these reactions can be controlled step-by-step. . . Asanas must have the dual qualities of alertness and relaxation. . .When these principles are correctly followed, asana practice will help a person endure and even minimize the external influences on the body such as age, climate, diet, and work” (Yoga Sutras of Patañjali in Desikachar, 1995, 180–181). Thus, learning to be both alert and relaxed while performing a posture can have a positive effect that generalizes to everyday life.

5. Even simple postures can be therapeutic. Hatha yoga classes will move you through a variety of postures. When you apply the principles of yoga and unify mind and body with breathing, even simple body positions—such as standing, sitting, or lying prone with some easy bends and twists—can elicit therapeutic effects. If you already practice Hatha yoga, you can use all the postures you know. But if you are not a yoga practitioner, use your natural body positioning, with some minor adjustments, to foster mindful mind-body unity.

TIP: Asanas involve more than moving the body into a posture and holding it there. Each asana contains three aspects: (1) moving into the pose, (2) holding the pose, and (3) coming out of the pose. Each aspect is important. So, when you perform the movements, be mindful that coming into and out of the pose is part of the process. Move gracefully, calmly, without rushing, and with balance and poise. Even when you are performing postures quickly, maintain gracefulness and control without straining.

TIP: Start from where you are. Begin with what you can do comfortably, without straining. Even if you are barely in the posture, but you have no discomfort, you are embarking on the path. If you are feeling tension, ease back until the posture can be held without strain. Work gradually, accept yourself, and your capacities will expand.

Standing postures can be an important part of a therapeutic yoga practice. Much of our life is spent standing. We balance upright and walk from the standing position. We gauge where we are and orient perceptually from our height. Often, we take for granted standing up, giving it little thought. But symbolically, to stand on your own two feet indicates independence and competence. Coming to an alert, aligned standing posture is a key to finding balance in your life.

How can you become more aligned? Simply standing or sitting upright by means of discipline is not the answer. Bring awareness to your body to find the answers. In the process, you develop new sensitivities.

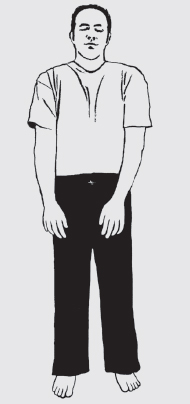

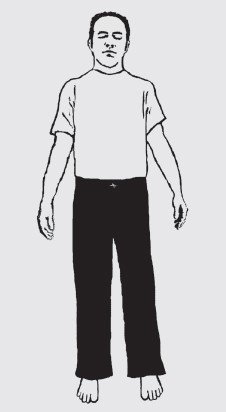

This series of exercises will help you discover your best standing posture, known in yoga as the mountain pose, tadasana. First, you will work with overall balance, and then you will refine your standing pose to be comfortably upright and relaxed.

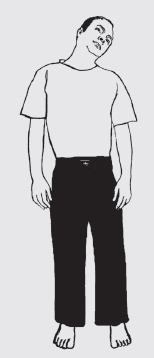

Discover your optimal alignment with gravity, just standing upright with awareness. Begin the process by standing with your feet together, ankles touching, and arms at your sides. If you feel uncomfortable, you can move your feet slightly apart. Stand up straight, but not stiffly. Keep your shoulders from slumping, and don’t let your back hunch. Look straight ahead, keeping your head upright and centered. Breathe comfortably and focus your attention on standing.

Now, move your legs slightly apart, approximately shoulder width apart. Place your weight evenly between both feet. Rock gently from side to side and feel your balance point shifting first to one leg and then to the other. Stop for a moment with your weight more on one foot and pay attention to how that side feels.

How long does it feel, from your ankle to the floor, from your knee to the floor, from your hip to the floor, and from your shoulder to the floor? Without moving, turn your attention to your other leg that has less weight on it. Do you perceive the two legs differently? Now rock gently back and forth several times. You will discover a place exactly between your two legs where balance is effortless and shared by both legs equally. Stand for a moment or two as you sense this balance point.

Next, try rocking very slightly forward and back.

You will feel some muscles tighten up as you shift forward and backward. As before, compare the length of the front of your body with the length of the back of your body. Now rock just a little, very gently, forward and back. Notice the point at which your muscles relax and your feet are firmly planted on the ground.

Just stand for a moment in that place between side-to-side and forward-and-back, where you are most relaxed, balanced, and aligned with gravity.

FIGURE 6.1 Just Standing

To refine your standing posture even further, find the best position for your knees, somewhere between bent and flexed. Begin by slightly bending your knees, keeping them directly over your ankles. Then, straighten them, flexing gently. Go back and forth between bending and straightening, discovering the point between, where your knees feel comfortably aligned and relaxed.

FIGURE 6.4 Bending Knees

FIGURE 6.5 Flexing Knees

Now push your pelvic area back slightly, letting your back arch a bit, feeling which muscles tighten as you do so. Then lightly push your pelvis forward, rounding your back slightly. Keep your attention on how your muscles feel as you gently move your pelvis forward and back several times, until you find that place in between, where everything feels relaxed. Stand for a moment and notice your body position.

FIGURE 6.6 Arched Back

FIGURE 6.7 Rounded Back

Rotate your shoulders forward and back feeling your upper back round and arch gently as you move. You will discover a comfortable place where your shoulders are aligned and comfortable. Notice your standing now.

FIGURE 6.8 Shoulders Forward

FIGURE 6.9 Shoulders Back

Finally, tilt your head from side to side until you discover the point at which your neck feels most comfortable. Then tilt your head forward and back slightly until you find the relaxed upright position for your head and neck.

FIGURE 6.10 Head Sideways

Now, just stand at ease. Focus your attention on standing and nothing else. Don’t label the experience with words. Instead, simply feel the sensations of standing, relaxed and alert. Breathe normally, in and out, allowing each breath to be comfortable and natural. Notice your body position from head to foot. Now with your body standing comfortably straight, you are firm and calm like a mountain.

A common stereotype of the asana used for yoga and mindfulness is to be seated cross-legged on the floor in an upright position. This practice derives from a tradition in India where people sat on the floor as part of their daily routines. But today, we are more accustomed to sitting in chairs, and some might feel awkward having to sit on the floor to do yoga and mindfulness. Fortunately, you can still practice, even if you are not able to sit comfortably cross-legged on the floor. Many of the sitting postures can be adapted to sitting in a chair, so long as you position your body correctly. Some of these adaptations are given later in this chapter. You may think of others.

Beginners who sit on the floor will find it easier to use a firm cushion that will raise their hips three to six inches. There are special cushions made for meditation. Using one can take the strain off the lower back and knees, making sitting on the floor easier. Eventually you may discover that you can sit comfortably without a pillow.

You should feel at ease with your posture for sitting. If you are bothered by how you feel when you attempt to sit in meditation, you may lose your concentration. Since concentration is important for making progress, take some time to find the most comfortable sitting position. As you become more flexible, varied positions will become easier to do.

Place a chair behind you and stand in mountain pose, focusing on your posture as you breathe naturally for several minutes. Then, after you have attuned to standing, stay attuned as you sit down into the chair. Notice how you move from the standing pose to the sitting pose. We encourage you to try this exercise in different ways: from standing to sitting on the floor, if you are able, or from standing to sitting on a chair. Let your breathing naturally coordinate with your movement. Keep your head gracefully poised upright, neck lightly stretched upward and not tensed, with chin lifted slightly. Then, when you are seated, move on to the next exercise to find your optimal sitting position.

Energy flows around and within the body, leaving through the hands and the feet. When seated cross-legged, energy can flow in a circle, continually nourishing the body rather than escaping. Thus, many traditional sitting positions are performed with legs crossed in various ways.

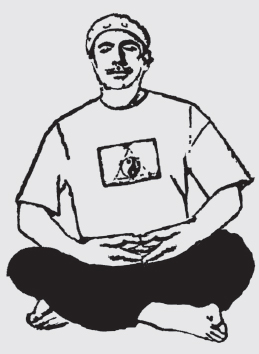

One of the easiest sitting positions is called easy pose. The easy pose is very similar to the cross-legged position you may have used as a child when sitting on the floor.

Draw your left foot in until the heel is as far under your right thigh as possible without forcing it. Then draw the right foot under the left thigh in the same way. Let your hands rest on your knees. Your legs will be crossed at the ankles. Most important is that you keep your spine, neck, and head balanced and held upright. This pose should be easy to maintain over an extended period.

When performing a yoga pose sitting in a chair, keep your spine, neck, and head upright just as in the floor-sitting positions. Make sure your thighs are parallel to the floor and lower legs perpendicular to the floor.

If the chair is too high to do this, you may need to place a book or pillow under your feet on the floor to raise them up. Let your hands rest on your knees, with your arms away from your rib cage.

FIGURE 6.12 Chair Sitting Posture

This exercise guides you in discovering alignment with gravity for the most comfortable sitting position. Sit cross-legged on the floor or on a small cushion. If floor sitting is uncomfortable, sit in a straight-backed chair, or perhaps on a low stool. Allow your arms to rest on your knees, and close your eyes. Rock back and forth gently and feel your sitting bones.

Experiment with swaying forward-and-back and then side-to-side as in the standing exercise to find your center. From this centered position, sit upright without being rigid, to allow your breathing passages to be open, permitting the air to flow freely in and out. Align your head upright in relation to your body, keeping your neck and shoulders as relaxed as possible. Maintain the position with your back comfortably straight and shoulders open without hunching forward.

FIGURE 6.13 Seated Rocking Sideways

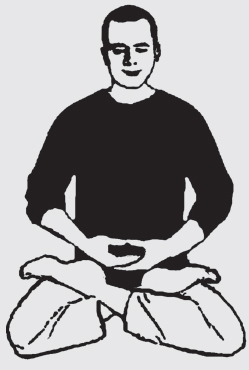

For those who take yoga classes, you might want to sit in the classic lotus pose. Lotus pose is an ancient position described in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. Some people find the lotus position easy to do without effort. Other people find it difficult because of their body type or level of flexibility. Keep in mind that comfort is always important, so don’t try to force your body into this position if it does not feel good.

To perform the lotus pose, place your right foot on the left thigh and the left foot on the right thigh. Your legs are locked, making it easy to maintain over time (as long as the position is comfortable). Let your hands rest palms up on your knees. Touch your thumb to your index finger, forming a circle.

FIGURE 6.14 Lotus Pose

Some people like to kneel, and yoga has such a sitting pose, the pelvic pose, vajrasana.

Kneel on the floor and then sit upright back on your heels. To be more comfortable, place a small cushion under the backs of your legs. Some people prefer this position to the cross-legged postures. Let your body be your guide as to how to sit most comfortably.

To know ourselves means to know our relationship with the world—not only with the world of ideas and people, but also with nature, with the things we possess. That is our life—life being relationship to the whole.

—J. Krishnamurti 1968, 94

Life is always about relationship. When lying down, there is a relationship to the supporting surface. You can learn about yourself through this relationship. The exercises for lying down are usually performed on a thin mat on the floor, but you can also use a couch in your office or home. Try to avoid an overly soft surface. Yoga mats are designed with the correct hardness.

Several of the classic postures performed lying down can be used to relax. Savasana and crocodile pose can relax the body from head to foot. These poses can be used for deep relaxation at appropriate times during the day, or to return to your calm center after deep emotional work.

The savasana pose can help you rejuvenate and revitalize. Being very restful, savasana can help to bring about a feeling of well-being.

Lie down on your back on the floor with your legs extended and arms at your side, palms facing up. Let your feet move apart and rotate slightly outward. Close your eyes.

Breathe comfortably. Scan your body with your attention and let go of any unnecessary tensions. If you experience tightening in the muscles of your face, stomach, neck, shoulders, or back, inhale, hold the muscles slightly, and exhale gently, letting the tension go a little with each exhalation. Try to permit as much relaxation as you can. Rest in this position for a few minutes.

If you feel tightness in your lower back in this asana, you can modify it by raising your knees while resting your feet flat on the floor. You may want to put a pillow under your knees and let your legs extend comfortably. This tends to flatten the lower back, allowing it to relax very deeply. As you feel your back muscles relax, you may be able to extend your legs flat into the corpse pose. If not, use the modified position when needed to allow yourself to relax.

The crocodile pose is also a relaxation posture, performed lying on your stomach. According to Indian folklore, the crocodile is considered one of nature’s most extraordinary creatures because it can be comfortable on the earth as well as in the water. Thus this pose symbolizes being able to fully relax under any circumstance. The crocodile pose can be helpful to the digestive system, massaging the abdomen slightly. Some people may find this pose more comfortable than savasana. If this is so for you, use the crocodile pose instead for deep relaxation.

Lie facedown on the floor. Let your legs stretch apart at a comfortable distance with your heels facing in and toes pointing out. Bend one arm to make a resting place for your forehead, placing your hand on your opposite shoulder, forming a triangle. Let your other hand come across your body at shoulder level and grasp the opposite shoulder. This position keeps your arms from moving as you totally relax.

Attitudes and feelings are expressed in how you hold your body. If you are feeling self-confident, you tend to stand upright, with shoulders squared, and rib cage lifted, whereas when feeling insecure or frightened, you might hunch forward or look down. The effect is reciprocal and so, by altering your posture, you can elicit a different emotional experience. The following poses are some examples of ways you can elicit feelings:

1. Confidence, warrior pose

2. Security and self-soothing, child pose

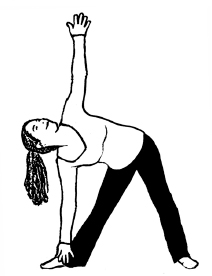

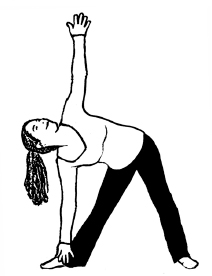

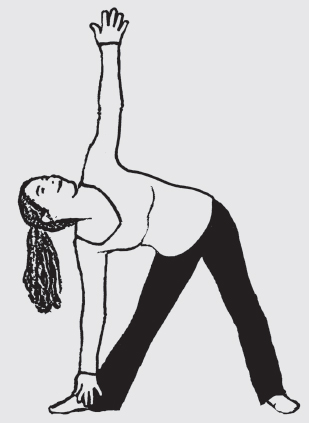

3. Flexibility, triangle pose

Many other poses can elicit helpful feelings. Now that you understand the principle, we encourage you to experiment to find what works best for you.

Confidence is reflected in how you hold your body. The warrior pose develops strength in your feet, arches, calves, and thighs. It also works the abdomen and shoulders. The position is symbolic of taking a strong stance, and you will feel your strength build as you embody this posture.

Begin by stepping your right leg out approximately three feet from your left leg. Bend your right, front knee, keeping the lower leg perpendicular and your thigh parallel to the floor so that your bent leg forms as close to a 90-degree angle as possible. Your left leg at the rear should be relatively straight and your left foot should be perpendicular to your right foot. Keep your hips level. As you move your feet into position, bring your arms up overhead. Then spread your arms out from your sides, directly over your legs, parallel to the floor with fingers held together and pointing straight out. Turn your head to face your front leg, keeping your neck and back straight. Lift your chest and stretch out through your arms and fingers. Focus your eyes facing forward as you hold the position and breathe in and out for as long as you can without discomfort.

Move slowly in and out of each position, keeping your motions smooth. Hold the posture for several minutes if you can, breathing gently, and then slowly switch sides moving the left leg out front.

Child pose offers a feeling of self-support that can be reassuring especially after dealing with disturbing emotions. You may also combine the child pose with savasana or crocodile pose, described earlier, to enhance the effect.

Sit on your feet in the pelvic pose, kneeling position. Bend forward slowly until your head touches the floor. Allow your arms to rest comfortably at your sides with your elbows bent so that they can rest on the floor.

You may need to shift or move slightly to find the most comfortable position. Breathe in a soft rhythm. Rest in this position

Narrow, rigid attitudes are often reflected in the body, which may become rigid and inflexible, like the attitude. You can start the process of loosening the hold of rigid perceptions by the simple act of stretching your body.

Place your legs approximately two feet apart, raise your arms out sideways to shoulder height, and inhale. Slowly bend to the left, keeping your arms stretched out and begin exhaling. Rotate your left hand down to lightly grasp your left leg as your right arm comes overhead and is pointing straight up as you continue to bend sideways.

From this position, relax your neck muscles and any other muscles that are not involved in this stretch and breathe normally. Slowly straighten as you inhale again and return to the starting position. Repeat the same motion on the other side.

Perform each movement slowly, with your mind fully focused. Don’t force the stretch and only go as far as you can comfortably. Pay attention to the subtle differences in tension and relaxation of various muscles. Observe sensations and positioning. Notice how your breathing affects your body position. Stay fully attentive and do not ignore your body’s counter reactions, and you will derive deep benefit. From the simple comes the profound.

FIGURE 6.20 Triangle Pose

1. Observe what you experienced following each exercise.

2. Notice which postures felt most comfortable and which ones were more difficult for you.

3. Make note of what areas of your body seemed chronically tight. Were some areas flexible?

4. Were you able to coordinate your breathing with the pose?

5. When did you keep your mind focused on the posture and when did it wander? If your mind wandered, what were your associations? Be curious and open, and observe objectively. Trust that the pieces of the puzzle of your inner being will emerge if you are accepting and supportive, and it will be more likely to happen.