He who has faith, who is intent on it (knowledge) and who has controlled his senses, obtains knowledge, and having obtained it, goes quickly to the highest peace.

—Bhagavad Gita

• Make the transition from breathing and posture practice to meditation

• Explore the two sides of withdrawal: doing and not doing

• Gain control over the distractions of external stimuli

• Discover how calm awareness develops with practice

Yoga and mindfulness teach you how to maintain control over what the ancients called the mind stuff and what we today refer to as stream of thought. The process begins with what is known in yoga as pratyahara, a set of meditations that teach you how to withdraw attention and turn it inward.

In everyday life, the senses are turned outward toward the material world. According to yoga philosophy, turning the senses outward distracts us from spiritual realities and higher consciousness. Yoga trains and disciplines the mind to observe without the senses or subjective consciousness intervening so that nothing interferes with direct perception. When your mind is withdrawn and disengaged, your consciousness is freed for meditation. This is achieved by the practice of pratyahara.

Everyone can benefit from an occasional time-out. As Wordsworth once said, “The world is too much with us.” Taking some time away from your busy day to practice pratyahara is renewing. Being able to deliberately withdraw your attention when needed also has therapeutic advantages. There are circumstances when you must endure a painful or difficult situation that can’t be changed. Or perhaps you have disturbing thoughts that you can’t put out of your mind. Or maybe you are easily distracted. This skill can be applied to help you handle difficulties so that you can meet adversity well. These inwardly focused, quiet meditative moments can add a new dimension to your life. You will develop greater self-control and a deep, lasting peace of mind.

A young girl came in to see us in a carefully matched outfit from shoes to purse to scarf. She told us that she was a planner. She liked things to be in order and lived her life in an organized way. She had just graduated from college and had a job all lined up for the fall. This summer she was doing temporary work to cover expenses. Even though everything seemed to be going well, Andrea was deluged with disturbing thoughts. She became obsessed with these thoughts until she would break down in tears. The thoughts haunted and frightened her. She tried to argue with her disturbing thoughts, because she knew they weren’t true, and even if they were, it didn’t matter. And yet, the more she thought about them, the more upset she became.

Andrea was a good candidate for pratyahara. She learned to withdraw her attention from outer objects, and redirect it at will. As her skills for external focus improved, she worked on withdrawing her attention from internal objects that vied for her attention, such as her thoughts. At first, this was difficult, because they seemed so real, and they had been with her for so long. We introduced her to mindfulness meditation to help her pay closer attention to her experience. As she became more focused, she had an insight: “I’m so wrapped up in my thoughts that I’m missing out on my life!” In time, as she gave less attention to her thoughts and more attention to the actual details of her life, the thoughts gradually faded and became easier to dismiss. Eventually, she was able to live in the present moment and truly enjoy it.

Pratyahara has two sides: not doing and doing. Withdrawing from distraction and unnecessary thought is “not doing.” By withdrawing from involvement in less important concerns, energy is conserved and consciousness is freed for positive use. Actively focusing inward and pinpointing the light of consciousness toward concerns that matter is the “doing” side. You can enhance your mental abilities by practicing both sides. Then meditation and mindfulness become easier to achieve.

• Allocate a few minutes of the day for pratyahara exercise.

• Pratyahara can be done in the morning, night, or after work.

• There is a natural rhythm for you, times when you might feel like withdrawing. Use those moments to practice pratyahara.

• Lie quietly and relax. At first, your thoughts may wander. Be patient, and you will be rewarded.

Pratyahara is the practice of withdrawing your attention from distractions, either from outer concerns and turning it inward, or from inner concerns and turning it outward, so it can be focused on more enlightened states of mind. Here is an easy way to begin the practice of withdrawal from distracting concerns.

Pour yourself a cool glass of water. Now, turn your attention to the glass as you pick it up. Feel the glass in your hand. Raise the glass to your lips. Do you feel the coolness of the glass as you take a sip? Pay attention to the water as it sits for a moment in your mouth. How does your mouth feel? Swallow the water and keep your attention focused on the cool sensation as the water travels down your throat to your stomach. Stay with the internal sensations as long as you can feel them. This exercise sets you on the path to pratyahara as you have successfully brought your attention from the outer world to your inner sensations.

Now you can begin to withdraw your attention. These exercises guide you through the process. Practice each one at different times and in different settings.

Begin by listening to the sounds outside. You might need to open a window. Notice what you hear, see, or smell. As you do so, let your breathing be relaxed and allow your body to become comfortable. Then withdraw your attention from these outer stimuli and bring your attention closer, to the immediate surroundings in the room. Notice as many details as you can: the temperature, the sounds that you hear, the objects that you see around you, the texture of the surface that you are sitting on, and the smells in the room. The outside stimuli will begin to fade away into the background as your immediate, closer surroundings become foreground. Continue to breathe comfortably and relax as you focus your attention on the room and what is within it.

Narrow the field even more by turning your attention away from the room and toward your inner experience of body sensations. You might find it easier to close your eyes now. Begin with your skin and notice if it feels warm or cool. Do you notice any other sensations? Breathe and relax. Concentrate on your muscles. Are some muscles tight and others loose? Moving inward, notice your heartbeat, your breathing, any sensations in your stomach. As you turn your attention inward, the sights and sounds of the room will begin to fade. Breathe comfortably and let your attention focus deeper inward.

Finally, focus on simply being calm and quiet. Sustain this tranquil, inwardly focused attention until you feel ready to stop. By withdrawing your senses stepwise from the outer environment, while simultaneously calming your energy with quiet breathing and relaxed muscles, you will develop a comfortably poised awareness. From the doing and not-doing practices of pratyahara, you are now ready to concentrate, contemplate, and meditate.

Begin by turning your attention away from the outer world toward the inner experience of your body. Notice what sensations you have there. Begin at your head. Pay attention to the boundaries of your face and neck. How are you holding your muscles? Are you tightening them unnecessarily? If possible, relax any unnecessary tightness that you notice.

Now direct your attention toward your shoulders. Mentally trace the width of your shoulders. Notice whether you are holding these muscles tightly. If so, let go. Continue down through your body, paying close attention to each area and then trying to relax any tension in that area. You may be surprised to notice sections that are tensed needlessly. If your attention wanders away from your body to outer concerns, bring it back. But don’t force yourself to relax. Simply notice where you can or cannot let go and gently continue loosening unnecessary tension.

Finally, lie down in savasana. Try to relax your thoughts just as you relaxed your body. Let go of thoughts themselves, such as what you need to do later or something that happened earlier. Do not be concerned about them, and instead, just notice that you are thinking. Stay in this peaceful, relaxed moment, following your own sensations and feelings. You don’t need to think about anything else. If your thoughts wander away and you are concerned that you did not do the exercise correctly, gently bring your thoughts back to calmness. Do your best without worrying about it. Pinpoint your thoughts on the present moment and enjoy the peaceful feeling right now. At first, start with 5 minutes and work your way up to 30 minutes. With practice, you will develop a deep sense of calm and well-being, a moment of samadhi.

You may be full of good intentions, but still have difficulty doing these exercises. If you have felt frustrated in your efforts, you may be putting up some resistance. These exercises will help you to overcome any resistance.

Perhaps you had difficulty directing your attention to your body because your thinking remained out of control. If you find your thoughts wandering even when you try to direct them, ask yourself: How would I quiet down a group of active children? You might let them be free out on a playground. At first, they will rush around everywhere, but eventually, they will settle down and play quietly. This same principle applies to stilling the thoughts that are racing through your mind. Paradoxically, when you don’t resist your instinctive resistance, you often present an opportunity for it to lessen. Then, it will be easier to withdraw your focus when and where you want. The strategy does not always work, but it often does, and so it is worth a try.

Sit quietly and let your thoughts run on, to jump around wherever they want to go, but with one difference: Stay aware of thoughts as they happen, but don’t lose touch with the part of you that observes. At first, you will see your thoughts come and go very quickly, like the young child running and jumping around, but in time, just as a child becomes settled, your thoughts will settle down into regular patterns at a manageable speed. Think about each thought is as it appears. Practice this meditation regularly, to reduce the rushing flow of thoughts. Then withdraw from concern about them.

If you have difficulty doing the pratyahara exercises, delve deeper to notice any hidden assumptions or concerns. Consider the ways you turn your attention to the outer world. For example, are you always planning what you will do next, rehearsing in your mind? Do you have concerns about the past that draw your attention now? Or perhaps you have certain attitudes or beliefs that might be interfering, such as thinking you should always be busy or that relaxation is akin to laziness.

Once you become aware of a habitual preoccupation or attitude, or perhaps an assumption that typically misdirects your attention, adjust your pratyahara practice. For example, if you notice yourself anticipating what you will be doing after your pratyahara session, stop planning, bring your attention back to the moment, and continue to withdraw inward. Or if you continually recount past events, let go of the memories for now. Whenever you realize you are thinking about distractions during pratyahara, gently return to present moment practice. At first, you may struggle, but eventually, extraneous thinking will stop. Then you will be able to enter dharana, the next limb.

Everyone will progress at a distinct pace; so don’t judge or chastise yourself. Just observe. If you are nonjudgmental, your mind will open up to you as an ally.

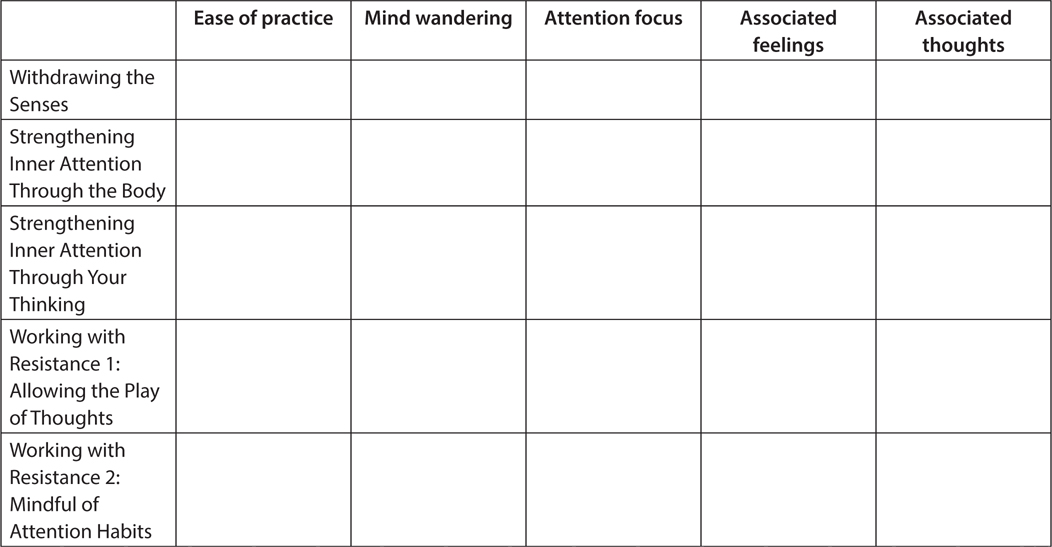

1. Observe what you experienced with each of these exercises.

2. Journaling can be especially helpful for dealing with resistance. Perform this exercise by writing down each thought you notice.

FIGURE 7.1 Feedback Chart on Pratyahara Meditations