CHAPTER 8

Exposure

CARLOS FROM EL SALVADOR

On June 28, 2012, three students associated with the Undocumented Migration Project summer field school spent the day with volunteers from the Tucson Samaritans.1 The research goal was to observe the organization’s humanitarian efforts and collect ethnographic and archaeological data on the various water and food drops that it maintains in the desert.2 The following are excerpts from an interview with UMP student Justine Drummond,3 who was with the Samaritans that day:

We were with Roberto [a Samaritan] when he got a phone call from two other volunteers. . . . They were asking if we could come out to Batamote Road and bring food and medical supplies to a migrant they had encountered. . . . We parked close to the GPS coordinates that were given to us by the volunteers and walked back to that location. One of them came out to meet us and brought us to the little wash where they were sitting with a young migrant named Carlos. Roberto, Linda, and Monica [the latter two also Samaritans] went to talk with him. Me and two other students sat away from Carlos and spoke to the volunteers who had been sitting with him. . . . They told us that he had been waiting by the side of the road when they drove past, so they stopped. He basically told them that he had been walking with a large group and the coyote had said that . . . Well, basically the smuggler was upset that there were people who were sick and weren’t able to go as fast as he wanted to go. So he had called out that the Border Patrol was near and everyone scattered.

In the chaos, Carlos found a woman from the group. I believe he also said that there was a man. He was traveling with two people. I am not entirely sure. He had been walking with them, and four hours before the volunteers had found him, he separated from the woman because she was sick and he wanted to get help. He’d been walking out of the hills and later pointed towards them to show us where he was coming from. . . . We sat down and had lunch with him and introduced ourselves. Every so often Border Patrol would drive by on Batamote Road. We couldn’t see the road but we could hear vehicles going by.

Carlos was nineteen years old and from El Salvador. He was wearing a blue shirt with a guitar printed on the front and had gray suede shoes and jeans on. On one wrist he had a pink nylon string that had his sister’s name on it. . . . He was glassy eyed and very quiet. He was smiling, though. He just seemed sorta physically exhausted and really dehydrated.

The decision was made to call the sheriff to take him to the hospital. . . . We started chatting with him as we walked back to the vehicles. At that point we were asking him how many people were in his group and where he was hiking from. That was when he started pointing at the Lobo Peak area.

I didn’t hear him say her name. He just said he was with two people, although the two initial volunteers who found him didn’t speak Spanish. He may have known their names but I’m not sure if anyone got them.

LEFT BEHIND

The trail had been cold for years. I first walked it in 2009 when I made my initial fieldwork trip to Arizona. During that visit, the area was a debris field of Red Bull cans, potato chip bags, dusty blue jeans, and various other items that people fleeing Border Patrol had either intentionally discarded or accidently lost along the way. It was an active landscape then. The fresh footprints of agents and the people they were chasing were clearly visible in the dirt and sand. A mosaic of heavy and imposing military-style boot prints mixed with the light impressions left by sneakers. Sometimes you would see fragments of shirts caught in the trees or freshly broken branches signaling where someone had recently tried to bushwhack. Walking through that part of the desert, you knew you were in the middle of something but couldn’t quite see it. Movement was happening, but it was in your blind spot.

One of the first migrant sites that I visited on that trail, later designated BK-3,4 felt fresh and overwhelming. There were mountains of backpacks, arroyos swollen with tangled clothes. The items left behind were shiny and new. Food containers were still sealed or their contents only half eaten. Animals and insects had not had time to finish off the perishables. Bottles still had water in them. It was like entering into some strange village where the sound of the anthropologist’s footsteps had sent everyone running mid-meal. During the initial summer we worked on that trail, I was constantly worried that we would accidentally walk up on some unsuspecting group of people resting in the shadows. Although we didn’t see anyone out there that year, it was clear we weren’t alone.

When I returned in 2010, many of the things left by migrants had been removed by some unknown person or organization. The desert had been decontaminated, its ghosts cleansed. Most of the evidence of hidden human occupation had been picked up and no doubt sent straight to the trash dump. What remained was largely sun bleached, worn, and breaking apart. After only a year, objects that had once seemed alive and vibrant were slowly dying, victims of solar radiation and rain. People assume that plastic water bottles and nylon backpacks will lie intact on the desert surface forever. It’s not true. Things out here fall apart. Clothes are reduced to shreds, leaving only the stitching behind. Backpacks evaporate leaving only metal zippers and polyurethane buckles. Water bottles turn brittle, crack into pieces, and blow away. When I visited again in 2011, barely anything was left to signal that people had once existed here. Nothing on the landscape suggested this route was used anymore.

The trail had become well known to law enforcement after a few years of heavy use. Some of the migrant sites in the area that we documented in 2009 were so large that we could see them using Google Earth. If we could do that, Border Patrol could no doubt spot them from the air-conditioned seats in the helicopters that border crossers refer to as el mosco (the fly). After many chases and arrests, the spot had become burned. La migra was smart about it. They started placing underground motion sensors along the trail to alert them anytime someone passed through. Migrants and smugglers are smarter. They simply stopped using the route altogether and moved someplace else. There is always a canyon or mountain trail that la migra doesn’t know about or that is too difficult for them to access on foot. Over five years of hiking, we rarely encountered Border Patrol agents on foot. They often lack the fortitude or motivation to head deep into the brush. Better to sit in your vehicle with a can of Skoal Long Cut Wintergreen and listen for ground sensor alerts. Migrants just keep heading deeper and deeper into the wild. Many get so deep that they eventually just disappear.

By 2011 I liked hiking this particular trail because it was familiar, like an old friend. I had cut my teeth out here, and many of the archaeological techniques that we now use to document and analyze migrant materials were first tested on this ground. I could also use the terrain to talk to students about the previous seasons’ archaeological work and joke with them when we inevitably would set off a motion sensor and soon have el mosco swooping down on us. We had a running bet as to how much money it cost the federal government each time their agents went up into the sky to spy on anthropologists, hikers, and cows. From the archaeological evidence, it was obvious that they weren’t catching many migrants out here anymore.

On the morning of July 2, 2012, I decide on a whim to revisit this old trail to check out a cleaned-up site that we have been studying as part of an ongoing project on desert conservation and its impacts on migrant material culture.5 We expect to find very little in the way of artifacts and certainly no people. I want to show a group of students what it looks like when the evidence of migration disappears. We park our rented SUV and begin the three-mile hike toward a high clearing near Lobo Peak that once had hundreds of backpacks strewn across its surface. Our caravan starts the long and arduous climb up and down several large rolling hills. We intermittently snake down into washes where the soft sand makes each step more difficult than the last. All we encounter are a few scattered remnants of backpacks and clothes. A weather-stressed shoe. An empty, rusted can of tuna.

Our group drops into a steep ravine after noticing a torn black tarp and a water bottle buried under a large mesquite tree. At one point someone hid here but the material looks old. Olivia Waterhouse, an undergraduate at Barnard College and one of the more precocious students in the group, decides to take a closer look. She wedges herself deep into the underbrush and pulls out a twisted wreckage of muddy clothes and plastic sheeting. The stuff has been there for a while, and it is difficult to determine what the items originally looked like. She keeps digging and, to our surprise, finds a vibrantly colored serape (Mexican blanket) buried deep beneath the pile of soiled clothes. The plastic sheeting has somehow protected it from several seasons of rain and mud flow. The blanket’s lines of deep blue and red cut a sharp contrast with the brown backdrop of the desert. It could have just come off a loom and is an unexpected find on a day when our goal is to find nothing. We deem the site too deteriorated to warrant filling out a field form. Still, we can’t leave the blanket behind. It is so rare to find something that beautiful and out of place in this context. “Take a GPS reading and bag it,” I say. Olivia puts it into her pack and we move on.

We come out of the ravine and begin the ascent up a hill toward a site known as BK-5. It’s a long, slow climb, the type you feel in your upper thighs and chest. The grade is deceiving and it’s not usually until you’re midway that you realize how tough the hike is. We have documented BK-5 on multiple occasions. Having eaten lunch under the shade of various trees there, I feel as familiar and comfortable with the place as one could possibly be with a landscape lately known more for being anonymous and unforgiving. The student leading our group hurriedly makes his way up the trail while the rest of us try to keep up with his overactive legs. He is far enough ahead that it is difficult to hear him when he starts yelling back at us, “Hey! Hey! There is someone up here! There is someone up here!” I can’t see what he is yelling about, but I figure it’s a migrant who has been left behind and needs water or first aid. I throw my pack down and begin to run up the trail. By the time I reach him, I can tell from his wide eyes that it is something more than a person with a sprained ankle. When I am finally close enough to see her, there is no mistaking that she is dead.

N31˚ 44′ 55″, W111˚ 12′ 24″

The eight of us stand around her in a semicircle. It is obvious that not everyone has seen a corpse before, because someone asks if she is really dead. Most of the students go and sit under a nearby tree while I figure out what to do next. I walk to the top of the hill to try to get cell phone reception. After fifteen minutes I finally get a 911 operator on the line. I tell her that we have found a dead body while hiking. I give her general directions to our location but it is a fairly useless endeavor: “About three miles northeast of Batamote Road near Lobo Peak.” She is not familiar with the area, so I give her the GPS coordinates of our location. She is not sure what they mean, so I tell her that we will send someone back to the road to get law enforcement. There is no way they are going to find us with verbal directions. Haeden Stewart, a graduate student from the University of Chicago, agrees to run back to the vehicle to get help. I tell the rest of the group that we will wait for the sheriff to arrive but in the meantime we need to document and photograph the scene. No one seems particularly enthusiastic about this prospect, me included.

At this point there is the realization that unpleasant work has to be done. I remind myself that directing a research project focused on human suffering and death in the desert means we can’t ignore certain parts of the social process just because it sickens us or breaks our hearts. This means looking at the body of this unknown woman up close and recording as much information as possible. This means taking photos. The decision to do this will later lead me to being questioned and criticized by some colleagues who don’t think we should have taken pictures of the body or used them in any publication. It makes readers and viewers uncomfortable, which is fine because it made (and continues to make) us as researchers uncomfortable. When this type of death starts to feel normal, that’s when we should worry. I start taking photos of her because it feels imperative to record what this type of death looks like up close. The objective is to document this moment for those who are not here.

I am well aware, though, that despite our best intentions, dangers and ethical issues can arise from circulating images such as these. As Susan Sontag warns, “The photographer’s intentions do not determine the meaning of the photograph, which will have its own career; blown by the whims and loyalties of the diverse communities that have use for it.”6 I cannot control the life of these pictures or the meanings that viewers will attach to them. My only hope is that these images can stand as undeniable material evidence that a woman died at N31˚ 44′ 55″, W111˚ 12′ 24″ and that witnesses saw her corpse in “flesh and blood.”7

She is lying face down in the dirt and it appears that she died while attempting to get up the hill. To get to this point, she easily walked more than 40 miles and likely crossed the Tumacácori Mountains. She is wearing generic brown and white running shoes, black stretch pants, and a long-sleeve camouflage shirt. The shirt is something you expect a deer hunter to wear, but over the last several years migrants and drug mules have adopted the fashion. The brown and green design blends in perfectly with the Sonoran backdrop this time of year. Her position lying face down, exposed on the side of a steep hill, suggests that her last moments were a painful crawl. She collapsed mid-hike. To be left on the trail like this likely means that she died alone out here.

Rigor mortis has set in and her fingers have started to curl. Her ankles are swollen to the point that her sneakers seem ready to pop off at any moment. The back of her pants are stained with excrement and are bubbling with copper-colored fluids that were expelled from her body upon death. It is surprisingly hard to look away. Dead only a few days, the body is in what forensic anthropologists term early decomposition: “Gray to green discoloration, some flesh relatively fresh . . . Bloating . . . Brown to black discoloration of arms and legs.”8 These descriptions don’t do justice to what bodies left out in the desert actually look like, smell like, or sound like. Nothing does. Against the quiet backdrop of the desert you can hear the buzzing of flies busily laying eggs on her, in her. There is a steady hissing of intestinal gases escaping from her bloated and distended stomach. It sounds like a slow-leaking tire.

N31˚ 44′ 55″, W111˚ 12′ 24″ (July 2, 2012). Photo by author.

High above, stiff-winged turkey vultures circle her corpse like black paper airplanes effortlessly surveying the scene. I count at least four of them and marvel at how quickly they have arrived. At this point in 2012, we are two weeks into our first round of forensic experiments, and I have recently been watching video footage of birds scavenging pig carcasses. The site of them now flying overhead is disturbing and I do my best to ignore them. I get close to the body and awkwardly scribble down more field notes: “No backpack or obvious personal possessions . . . a bottle of electrolyte fluids tucked under shoulder and face.” As I lean in to look at her, the wind whips across her body sending the sweet smell and taste of rotting flesh directly into my nostrils and mouth. It is the taste of la muerte.

After several days in the boiling summer heat her body has begun to change. Her skin has started to blacken and mummify and the bloating is beginning to obscure some of her physical features. While parts of her are transforming into unfamiliar shapes and colors, her striking jet-black hair and the ponytail holder wrapped around her right wrist hint at the person she once was. I focus on her hair. It is smooth; the color of smoky obsidian. It’s possibly the darkest hair I have ever seen, and its texture gives the impression that she is still alive. I think about reaching down to touch her, but I can’t. She has been out here too long and I know that her skin will not feel human. I want to see her face but don’t dare roll the body over. This is a “crime scene” and I don’t want to destroy any evidence. I start thinking about who she might have been in life. Was she a kind person? What did her laugh sound like? What compelled her to enter this desert? Would she be angry that I am taking her picture? Finally I ask Olivia to get out the blanket that we found, and we use it to cover her. It makes those of us still alive feel better.

I go over and sit with the remaining group of students under a tree a short distance from the body. The silence among us is tense and only occasionally broken when a breeze comes through and rustles the branches of nearby mesquite trees. Out of the blue someone starts crying uncontrollably and is immediately consoled by a neighbor’s kind embrace. Others sigh deeply and someone angrily walks off into the distance to be alone. We sit quietly for what seems an eternity. Vultures continue to patiently circle overhead. They are simultaneously implicated in and oblivious to the complex human drama playing out below them. All they know is that we have disrupted their lunch plans.

Esperando. Photo by author.

I want to say something to our group that will comfort us or make this death seem peaceful or dignified. It’s a ridiculous thought. There is nothing you can say in this scenario that doesn’t sound contrived. Months later someone will corner me after a talk and complain that the photos I showed of this woman’s body robbed her of her dignity. I will point out that the deaths that migrants experience in the Sonoran Desert are anything but dignified. That is the point. This is what “Prevention Through Deterrence” looks like. These photographs should disturb us, because the disturbing reality is that right now corpses lie rotting on the desert floor and there aren’t enough witnesses. This invisibility is a crucial part of both the suffering and the necroviolence that emerge from the hybrid collectif. As Timothy Pachirat notes, we live in a world where “power operates through the creation of distance and concealment and [where] our understandings of ‘progress’ and ‘civilization’ are inseparable from, and perhaps even synonymous with, the concealment (but not elimination) of what is increasingly rendered physically and morally repugnant.”9 These photos thus make visible the human impact of a United States border enforcement policy intended to kill people, and they provide compelling evidence that we don’t need to go to “exotic” places to get “full frontal views of the dead and dying.”10 The dead live in our backyard; they are the human grist for the sovereignty machine. You need only “luck” to catch a glimpse of the dead before they are erased by the hybrid collectif.

Desert border crossings are cruel, brutal affairs in which people often die slowly and painfully from hyperthermia, dehydration, heatstroke, and a variety of other related ailments. To paint these deaths in any other way is both a denial of the harsh desert reality and a disservice to those who have experienced it. Judith Butler reminds us that the American public rarely gets to see these types of photos for fear of causing internal dissent or undermining nationalistic projects: “Certain images do not appear in the media, certain names of the dead are not utterable, certain losses are not avowed as losses, and violence is derealized and diffused. . . . The violence that we inflict on others is only—and always—selectively brought into public view.” It is unclear, though, what impact the photos of this woman’s body will have on those who flip through the pages of this book. Will the images evoke sadness or disgust? Does looking behind the curtain at the inner workings of US border enforcement elicit responses that get us closer to political action? Can these images effectively and affectively pierce the American public’s consciousness? Or, as poet Sean Thomas Dougherty writes in reference to Kevin Carter’s (in)famous photo of a “starving Sudanese child being stalked by a vulture,” will the violence depicted here become nothing more than an “aesthetic” capable only of evoking appreciation?11

Sitting there on that dusty afternoon, I finally blurt out, “At least we got to her before the vultures did.”

“BODIES”

It takes Haeden and another student close to five hours to find a sheriff and then bring him back to where the body is. When a migrant dies, he or she stops being the federal government’s problem and subsequently the case is handed over to the county. However, in rural areas the Border Patrol often provides local law enforcement with logistical support. In our case, a lone sheriff shows up with three Border Patrol agents in tow. Two of the agents are young and are accompanied by a senior officer. They have hiked the three miles in from the road, pulling a wheeled stretcher specially equipped with off-road tires.

The sheriff is polite and cognizant of the fact that six of us have been sitting with her body for hours. He knows that we are going to scrutinize his every move to make sure she is treated respectfully. It is obvious the sheriff has done this numerous times before. He quickly dons light-blue medical gloves, pulls out his point-and-shoot camera, and snaps a few photos of the corpse. He then takes a GPS reading.

“Was that blanket on top of her like that?”

“No, we covered her up.”

“Did she have anything with her?”

“She had no obvious possessions outside of that bottle of electrolit.”

“All right, time to move her.”

This is the extent of the investigation of this death. No survey is done near the body to look for additional personal effects. The trail is not checked for other people or corpses. Some photos are taken and geographic coordinates are recorded. It takes a total of five minutes.

The sheriff looks at the two young Border Patrol agents, one Mexican American, the other white, and says they need to help him move the body. The senior agent starts fiddling with the equipment on his tactical vest and then walks up the hill. He is clearly not going to be involved in this next stage. The young agents are visibly uncomfortable with the whole scene. Olivia asks the white agent, who seems to be the more nervous of the two, how old he is. “Twenty-two,” he says. Four of the students in our group are older than him. The agents are handed medical gloves, and the sheriff starts planning how he will move her. “Hopefully, she doesn’t burst when we pick her up,” he says. The white agent nervously laughs and seems to be unsure if that was a joke.

They wheel the stretcher close to her and lay a white body bag on the ground. “We gotta roll her over and put her in the bag because she is gonna leak,” he tells the men. The sheriff grabs her arm and shoulder while the agents reach down to take hold of her feet. As the white agent gets close to her, he catches a whiff of her rotting flesh. He drops her feet, steps back, and starts dry heaving. His eyes are watering and he is holding himself to prevent from vomiting. As he starts to crack a joke about how “gross” it is, he notices that eight of us are coldly staring at him. The irony of this scene is undeniable: Border Patrol routinely refer to living migrants as “bodies” in everyday discourse,12 but many of them seem totally unprepared for dealing with the actual dead ones. The sheriff gives the agent a stern look, which forces him to regain composure. “All right, we’re gonna flip her on three.” They reach down and stiffly roll her over.

As her body turns, I see what is left of her face. It is frightening and unrecognizable as human. The mouth is a gnarled purple and black hole that obscures the rest of her features. I can’t see her eyes because the mouth is too hard to look away from. The skin around the lips is stretched out of shape as though it has been melted. Her nose is smashed in and pushed up. She died face down, and the flesh on the front side of her skull has softened and contorted to fit around the dirt and rocks beneath her. The scene is a pastiche of metallic gray and pea green. Whatever beauty and humanity that once existed in her face has been replaced by a stone-colored ghoul stuck in mid-scream. It’s a look you can never get away from.

They get her leaking body into the bag and zip it up. She still needs to be lifted onto the stretcher. Even though she is now hidden behind a shroud of white plastic, the two agents are still uncomfortable with touching her. As they struggle to get a grip, I step in to help. I grab one ankle; it is rock hard like the leg of a coffee table. There is a collective heave. By this time another agent has arrived on an ATV. She is loaded onto the back of the four-wheeler and driven away. We pick up our things and silently begin the three-mile march back to our vehicle.

MEDICAL EXAMINER

All migrant bodies recovered in the southern part of the Tucson Sector are delivered to the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner (PCOME) for processing. Since 2000, the office has received an annual average of 184 deceased migrants. As of January 2013, approximately 900 of these human remains were unidentified and unclaimed.13 Attaching names to these recovered bodies is not an easy task. The environmental conditions can quickly decompose human tissue, animals can rapidly disarticulate and scatter skeletons, and people are often found without documents that could aid in their identification. The PCOME employs a small team of anthropologists who have been tirelessly working for years both to identify bodies and to help the families of the missing file reports. One member of this team is Robin Reineke, a cultural anthropologist who has been working with the families of the missing and dead since 2006. In 2013 she founded the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping people reunite with loved ones who lose their lives while migrating. Robin is a good friend who, just a few weeks before we found the body, had given my students a tour of her office.

Unidentified human remains from the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner. Photo by Michael Wells.

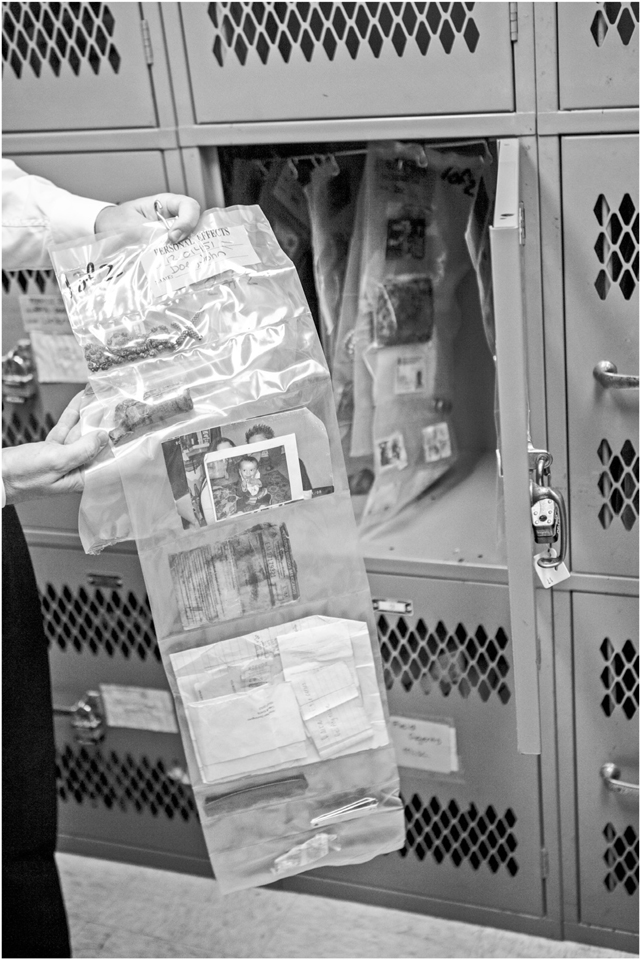

Visiting the medical examiner’s office is a somber affair that brings you face to face with both migrant death and the lonely existence of the unclaimed. It can be emotionally difficult and physically nauseating to see the areas where the county stores animal-gnawed human bone fragments and pungent body bags that are leaking fluids. For some visitors, however, the most difficult part of the tour is a tiny windowless room where the personal possessions of those yet to be identified are kept. If the sour smell of rotting corpses doesn’t get you, looking at the friendship bracelets, wallet-sized photos of babies, or prayer cards sometimes found with unidentified bodies often will. Although these items may elicit emotions, they can’t necessarily tell you who these dead people were in life. As the staff at the PCOME can attest, migrants often travel with forged identification documents, documents belonging to someone else, or no ID at all.14 The body that we found was taken directly to the medical examiner’s office and placed in one of its large storage freezers. She had no identification and no personal effects.

Personal effects of the unidentified, Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner. Photo by Michael Wells

That evening I call Robin and tell her what happened. She promises to keep us up-to-date on any developments with the case. Two weeks later I receive an email:

Hi Jason,

Just a quick update regarding the woman that your group found—

The case number is 12–01567, and as of yet, she has not been identified. I just spoke with [one] of the Samaritans. . . . She relayed some useful information regarding the people left behind by the Salvadoran man. Here is what I got from her on the phone. Let me know if you have any corrections or more information:

7/17/12: I received a call from [someone] from the Samaritans group, who has been communicating with those who found the body of 12–1567. She said that the day before the body was located,15 several Samaritan volunteers in the same area (4.5 miles from Arivaca Road) encountered a young man by the name of Carlos who was from El Salvador.

He said that he had recently left behind two fellow travelers who were in serious medical distress. The names of the two people he left behind were: 38 y/o Marsela Haguipolla (or Maricela Ahguipolla) of either Guatemala or Ecuador, and an older man by the name of Tony Gonzales of Ecuador. The older man was 70 years old. . . . It isn’t certain that this group is related to ML 12–1567, but it is highly likely.

I will contact Guatemalan and Ecuadoran consulates regarding new missing person cases.

Apparently, Carlos knew their names after all.