CHAPTER 11

We Will Wait Until You Get Here

JOSÉ’S ROOM

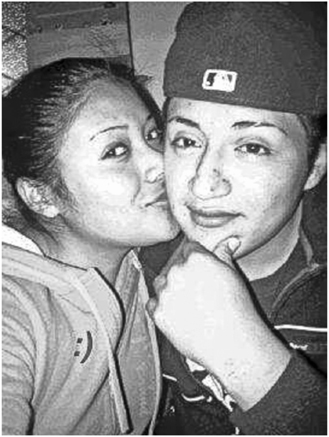

José Tacuri’s room looks like those of most other fifteen-year-olds. On the cusp of manhood, his windowless cement cuartito in a tiny house in a working-class barrio of Cuenca is decorated with a combination of items from his fading childhood and his burgeoning adolescence. A couple of white teddy bears are squirreled away in the corner; a comforter decorated with characters from the Disney movie Cars blankets his bed. These childish things are juxtaposed to a light-gray suit hanging in the corner next to a pile of hoodies, baggy jeans, and baseball caps stitched with New York Yankees and New York Knicks logos. Nueva York is always on his mind. This hip-hop wardrobe, along with a few homemade tattoos and piercings, bite the style of Ñengo Flow, José’s favorite reggaeton singer. In practically every recent photo of José, he gives the impression that he is posing for the cover of a mix-tape. “Real G for life, mami!” Next to his clothes is an image of Jesus Christ and a retainer case. He may have some ghetto ink and a little swagger in his step, but the kid still wears orthodontics.

On the middle of his bed is a pillow that José’s girlfriend, Tamara, gave him for his fifteenth birthday. The airbrushed message on it reads: “Happy Birthday. Today is a special day where God has given you another year of life. I only hope that you can have many more years so that we can be together. With all my heart I want to tell you that I love you.” José’s room looks like a lot of other teenager’s rooms. The only difference is that this place is frozen in time. Nothing here has moved since he left for the United States and disappeared in the Arizona desert just south of Arivaca.

José (age fifteen). Photo by Michael Wells.

A few days after I spoke with Vanessa in July 2013, José Tacuri’s family in New York called me and explained what had happened to him. Over the next several weeks, I helped them file a missing person report with the Colibrí Center for Human Rights in Tucson, the same organization that helped identify Maricela. I also acted as a general helpline when questions arose about what the family could be doing to find him. Because of my familiarity with the Sonoran Desert, I thought that getting more details about the route that José took could help us triangulate his last known whereabouts and aid in a search. Two months after he went missing, Mike Wells and I traveled to New York for the first of many meetings with José’s parents and the two cousins he had been traveling with. During that initial visit, I interviewed his cousins about the long trip they had taken from Ecuador to Arizona, and began my own journey to learn about José’s young life and the reasons for his migration. Four months after meeting his family in New York, Mike and I found ourselves in a house in Cuenca staring at the bedroom of a ghost.

If seeing the ravaged body of a person you love is the physical manifestation of Sonoran Desert necroviolence, then having no corpse at all is its spectral form. Maybe with time and therapy, if one can even conceptualize the latter as an option, or perhaps enough booze or drugs, you can learn to block out grotesque images: the odd geometries of cross-sectioned radials and ulnas; brittle skin peeling off laughing skulls; seashell-colored long bones heaped in a pile like the remnants of some great carnivore’s recent meal. Maybe you are lucky and didn’t open the coffin, so you never saw what really happened to your wife’s body. You were just happy to have her back. You can always kiss those wrinkled photos of the good times or catch glimpses of her in the faces of your children. The kids remind you of who she was and the beauty and vitality that once lived in her eyes. But how do you grieve when there are no bones to mourn over, no coffin to keep sealed tight? How do you move on when the uncertainty of what happened to someone you love won’t let you? How do you find closure when the missing come to you in dreams every night pleading for your help? For José’s family, his room serves as both a time capsule of who he once was and a painful reminder that his fate remains unknown. This space is the material representation of the family’s perpetual state of grief. As I sit with José’s grandmother doña Lorena in her kitchen in Cuenca, she tells me:

“I only hope that you can have many more years so that we can be together.” Photo courtesy of the Tacuri family.

Dear God! We’ve been praying that he will show up. We’ve been waiting for a long time. We pray and we cry almost every single day, but he still doesn’t appear. There is no peace for us. We are here all alone suffering, crying day and night. We ask God to give us some news. We have gone everywhere we can to get information, but there is nothing. We will never find peace until José comes back. He can return in any form, but we just need him to appear. We need to know something. Whatever it is that has happened to him, we want to know so that we don’t suffer anymore and so that we don’t think about it anymore. His parents, his aunts and uncles, everyone is suffering. We hope one day to reach God because only he knows where he is. It is hard. [cries] It is so hard to know so little. Is he over there in the United States? Is he alive? We are poor. It was poverty that made his parents leave to support their kids, and they are in New York suffering because he hasn’t appeared. They are suffering and waiting for him to show up but nothing happens.

LEFT BEHIND

Scholars have long noted that transnational migration has dramatic effects on family structure and the relationship between those who leave and those who stay.1 José’s experience as the child of parents who migrated without documents to the United States is quite common. Unable to adequately provide for his five children in Cuenca, including a disabled daughter, José’s dad, Gustavo, made the difficult decision to leave for New York when his son was just ten years old. Within a year of his arrival his wife, Paulina, decided to join him. Two people could put more food on the table than one. Both newly employed, they were soon able to send money home regularly. This ensured that their children could eat and go to school and that their sick daughter could get the costly medical attention she needed. These remittances also guaranteed that José didn’t have to work. Instead, he could be the kid on the block who had a laptop, an iPod, expensive kicks, and an overabundance of clothing emblazoned with the words “New York.” He could take his girlfriend out to the movies and treat his cousins to pizza whenever he wanted.

José’s aunts and grandmother assumed the role of caregivers for him and his siblings, but he could Skype with Mami and Papi whenever he wanted because their tiny rented house now had WiFi. This Nueva York to Cuenca virtual parenting was a scene out of Alex Rivera’s sci-fi movie Sleep Dealer. But, as you can imagine, long-distance parenting isn’t the same as being there. It never is. Despite the comfort that his family’s newfound economic stability afforded and his own conspicuous consumption, José began to suffer from what some in Ecuador call el dolor de dólares (the pain of dollars), a double-edged phrase that refers to both the feelings of abandonment that children of migrants experience and their faraway parents’ attempts to assuage this pain with American cash and gifts.2

As with many children in his situation, José’s feelings of parental neglect and abandonment led to rebellion. He dropped out of school. He stopped going to catechism. He discovered his love of chelas (beers) and was soon a regular at the all-night parties down at the neighborhood soccer field. By the time he was a teenager, his tías and abuela got into the routine of looking for him on the streets at all hours of the night. Rebelling is easy when there is no one around to crack the parental whip.

The stucco and shingle two-story compound in New York occupied by various members of the Tacuri clan and their young offspring is enormous by Cuenca standards. It reflects the relative affluence that some new immigrants are able to achieve after pooling years of cut-rate wages earned by working seventy-hour weeks. Several late-model sports utility vehicles and work trucks fill the expansive gravel driveway. Construction tools and sawhorses function as patio furniture. The palatial backyard is littered with the accoutrements of childhood: soccer balls are everywhere; a sparkling white slide and swing set look as if they just came out of a Pottery Barn Kids catalog; muddy sneakers of all sizes and colors sit in a pile next to the front door. In the living room a flat-screen TV sits next to a cabinet full of gold and porcelain knickknacks. One corner of the room is dedicated to housing teddy bears, strollers for baby dolls, and other important child treasures. A yipping white ball of fur runs wild through the place, snapping at my ankles and growling every time I try to pet him. It is a twenty-first-century Norman Rockwell series on the American immigrant dream. Like many immigrant dreams, though, this one is only half realized. José’s dad, Gustavo, sits in this gilded American cage and recounts the detrimental impact that his migration had on his son.

Gustavo: When I was in Cuenca, José was my right hand. He was always with me. We were inseparable. But when I came to this country, he became a really rebellious child. I called him and asked, “José, why have you changed?” He said to me, “No, Papi, it’s your fault. You left me. We were like brothers. You were my everything and you left me. It’s your fault that I’m like this.” I told him, “Look, I didn’t come here to New York because I wanted to. I came here to get ahead, because in Ecuador I can’t give you the things that you need.” I left when he was ten to provide for him and my family. He didn’t really understand these things at the time. I kept asking him why he was acting up. I asked him why he had changed from being such a good kid. All he kept saying was that he wanted to come here to New York, but I didn’t understand why. He had everything there in Cuenca. He kept saying that my wife and I were to blame. He said he felt empty inside. He said he would go home and we wouldn’t be there. He told me that being reunited with us would fill his emptiness inside.

In her analysis of Ecuadoran migration patterns in the 1990s and their impact on family life, Ann Miles noted that some undocumented migrants from Cuenca managed, at great risk and cost, to return home to visit family members every few years.3 Following the escalation of border security in the wake of 9/11, this pattern of periodic return became too dangerous and prohibitively expensive, especially for non-Mexican migrants like José’s parents.4 Policy analysts have since shown that these increased dangers and economic costs have led to a new, permanently settled undocumented population in the United States, people who, rather than risk a visit home to see family, are more likely to send money for their spouses and children to join them.5 Those who make it through the Sonoran Desert hybrid collectif rarely want to brave it a second time.

After years of pleading with his parents, José finally convinced them it was time for him to join them in New York.

Gustavo: In 2012 I wanted to bring José, but I wasn’t thinking about it seriously. He was still a kid. I told him, “Don’t worry, when it’s your time, you’ll come.” A year passed, and this year in March he surprised me by saying, “Papi, I want to come and be with you.” I said, “No, you’re crazy. What are you going to do here? You’re too young to come here.” He was young but big for his age. He was bigger than me [referring to him in past tense]. He said, “Help me to get there.” I told him, “No, son, you shouldn’t come.” But he said, “I’m alone here.” He was saying these things to me. I said, “Look, I’m here in New York for you guys. I left and suffer so that you can be OK.” He said, “Papi, I want to come and help you. I miss you so much. It’s been so long.” So he convinced me. I said, “OK, I am going to help you. We are going to contract someone there in Ecuador so that you can leave. We are going to bring you here. We will put our trust in God. El camino es duro [The migrant trail is hard]. I know because I have gone through it, but with faith we will get through.” A month passed and I paid some money. It was just a few hours’ notice to start the trip. José was having second thoughts by this time. I had only paid like a thousand dollars or something, so I said, “It’s time but I don’t really want you to come. You should stay there with your brothers and sisters and take care of them.” He told me, “No, I decided to leave and I am leaving. I want to be with you. Papi, don’t worry. I’m going to get there.”

“MOUNTAINS AND MOUNTAINS”

On April 3, 2013, José left Cuenca with two cousins, thirteen-year-old Felipe and nineteen-year-old Manny.6 Much like Christian’s trip in 2001, theirs lasted several months but in comparison was relatively uneventful. After leaving Guayaquil by plane, the three of them crossed multiple borders by car and bus. After less than two weeks of travel they arrived in Mexico. Once in Mexico City, the cousins were sent to different safe houses where they then spent forty-five days waiting for transport to Nogales.7 Unable to leave their houses, they tried to keep themselves busy. They mostly watched TV and paced around a small courtyard. The house where José was kept had Internet, and he was able to periodically log on to Facebook when his smuggler let him (for a fee of course).

Finally, after a month and a half of being cooped up indoors, José’s cousins were loaded into the luggage compartment of a passenger bus, given a bucket to urinate in, and told not to make any noise. For two cramped days Manny and Felipe lay quietly under the bus while dozens of unknowing passengers sitting above them snoozed, read magazines, and stared out their windows at the northern Mexican countryside. Although the details of how José got to Nogales are currently vague, it was likely a trip similar to what his cousins experienced. When they finally reached the border, the three boys were reunited and taken to a safe house where they waited, along with dozens of other migrants, for their guide to tell them when it was time to try their luck. Ten days after arriving in the Nogales, a car showed up one night and drove them to the edge of the desert.

Felipe: We left the house in Nogales at night and were dropped off underneath a puente [bridge or overpass]. It only took like twenty minutes in the car to get from the house to the puente. Everyone was carrying a black backpack and their one bottle of water. A gallon of water. Some bottles were white and some were painted black. . . . José was wearing black Air Jordans with black pants, a black sweathshirt, a black shirt, and black hat with red letters on it. Everyone had black clothes on.

Manny: José had a rosary, a prayer card, and a chain with an owl on it that his girlfriend gave him. He was wearing a belt that had phone numbers written on it. It had his dad’s cell phone and house numbers. He had no identification.

Air Jordan, Sonoran Desert, July 2010. Photo by Michael Wells.

Felipe: We crossed a fence and then started walking. We were traveling with two guides. There were around forty people in our group. One of the guides was named Scooby. I don’t remember the other one’s name. . . . We climbed a hill and at the bottom we crossed another fence. When we climbed the first hill we could see the city of Nogales, and then it disappeared. We walked all night and then rested near a rancho around 4 or 5 A.M. We slept in an abandoned house there. In the morning we started walking again.

Manny: We left from the puente. We walked a little bit and then climbed a mountain. After the mountain it got flat, and then there was a road with a house on it. After we crossed the road, there was nothing, just mountains and mountains. We walked past a tall mountain that had two blinking antennas on it. They had red blinking lights. The guides called it La Montaña de Cerdo [Pig Mountain].

Felipe: Our group separated that next day. Me, José, and Manny stayed together with Scooby. . . . We would climb a hill and Scooby would be waiting at the top for people. On the second day of walking we got to the start of the hill at about 6 A.M. and rested. José’s shoes were starting to fall apart. The soles were coming unglued. José kept stopping to sit and drink water. We were giving him water so he could keep going. We then climbed a hill and dropped down to a flat area where there wasn’t any shade or trees. It was impossible to hide there.

Manny: We had rested at the bottom of a hill for ten minutes when my cousin José started to sleep. He didn’t want to get up. Everytime we stopped to rest, he would try to sleep. The guide would say, “We are going to rest and catch your breath and then we are going to start walking again. Don’t sleep.” Well, José started to sleep. It was the heat. The heat will get you. It robs you of energy. We really didn’t have much to drink. José had water in his backpack but he needed more. He started to drink a lot of water. He was just getting thirstier and thirstier. We had brought sueros [electrolyte solution] and gave them to him. He finished everything. He couldn’t control himself.

Felipe: He stopped walking around 7 A.M. He couldn’t go on. José fell down and Scooby started kicking him. Scooby was saying, “Get up or I am going to keep kicking you.” José’s leg gave out, and he just slumped down on the ground. He said that he’d had enough. Scooby was yelling, “You need to get up or I’m going to beat you.” José was sitting on the ground looking dazed [makes woozy head movements], and Scooby just kept kicking him. He tried to get up but fell with all his weight. He was falling on bushes and the branches were breaking. He fell three times and the last time he couldn’t get up. He was very sleepy and his eyes were half open. We were all kind of like that but José also had the flu. When we left Nogales he was sick. He said he was going to turn himself in. He told me, “I can’t go on, but you should.”

Manny: His feet wouldn’t let him go anymore. He was on the ground and said, “I am going to turn myself in.” Immigration was all around at this point. Where we left him there was Border Patrol everywhere.

Felipe: There were helicopters around because, the day before, they were catching a lot of people in our group. We told José we were going to keep going and we left him sitting at the bottom of the hill. He was in a spot where there was no place to hide, no trees or anything. José had food and a little bottle of water that I gave him. We walked to the next hill where Scooby was waiting. That was the last time we saw him.

A day and half after leaving him behind, the cousins and their guide were spotted by Border Patrol and chased into the mountains. It was at this point that Scooby abandoned them. They were now alone, lost, and out of food and water. To compound issues, thirteen-year-old Felipe was dehydrated to the point that he began coughing up blood. At daybreak they started walking until they stumbled upon a lagoon and were able to fill their bottles with murky liquid. That morning they somehow found their way to Arivaca Road, where they were quickly picked up by Border Patrol. As the crow flies, they had walked almost 30 miles through multiple mountain ranges. Upon mapping the coordinates of where they were apprehended, I realized that Felipe and Manny were caught 8 miles directly south of where Maricela’s body was found. It appears that they walked the same route that she did.

When they finally spoke to their families from federal detention days later, Manny and Felipe reported that José had stayed behind. Despite the fact that they left him in an area with heavy Border Patrol presence, José never turned himself in. At the end of our first interview Manny remarked to me, “I don’t know why he didn’t turn himself in at that moment. Maybe he kept walking. I’m not sure what happened.”

AMBIGUOUS LOSS

The uncertainty, pain, and suffering that follow in the wake of a loved one’s disappearance are devastating, to say the least. For many, it’s like a nightmare you can’t wake up from. You never stop wondering what happened to your son, daughter, brother, or wife. You never stop searching for answers even when there is no hope of finding them. Just ask the families of soldiers who go missing in action, the relatives of the passengers on board Malaysian flight 370, or the people still looking for the bodies of those who were swallowed up when the World Trade Center towers collapsed on September 11, 2001. Sufferers of this type of loss can find themselves in an eternal state of grief, confusion, and desperation. Clinical psychologists call this phenomenon ambiguous loss,8 and some argue that it is the pinnacle of human sorrow: “[it] is the most stressful loss because it defies resolution and creates confused perceptions about who is in or out of a particular family. With a clear-cut loss, there is more clarity—a death certificate, mourning rituals, and the opportunity to honor and dispose of remains. With ambiguous loss, none of these markers exists. The clarity needed for boundary maintenance (in the sociological sense) or closure (in the psychological sense) is unattainable.”9

On June 2, 2013, the Sonoran Desert did what Border Patrol strategists wanted it to do. It deterred José Tacuri from entering into the United States. But instead of just stopping him, the hybrid collectif swallowed him alive, erased all traces of him, and sent shockwaves of grief felt as close as New York City and as far as Ecuador. This erasure was not, however, an “accident” or act of nature. It was part of a clearly laid out federal security plan, whose efficacy is measured by how many people it “deters.”10 Unfortunately, there are no reliable statistics on the number of people who have gone missing and are presumed dead in the desert, a point recognized by those in charge of evaluating Prevention Through Deterrence: “The fact that a number of bodies may remain undiscovered in the desert also raises doubts about the accuracy of counts of migrant deaths. . . . [T]he total number of bodies that have not been found is ultimately unknown.”11

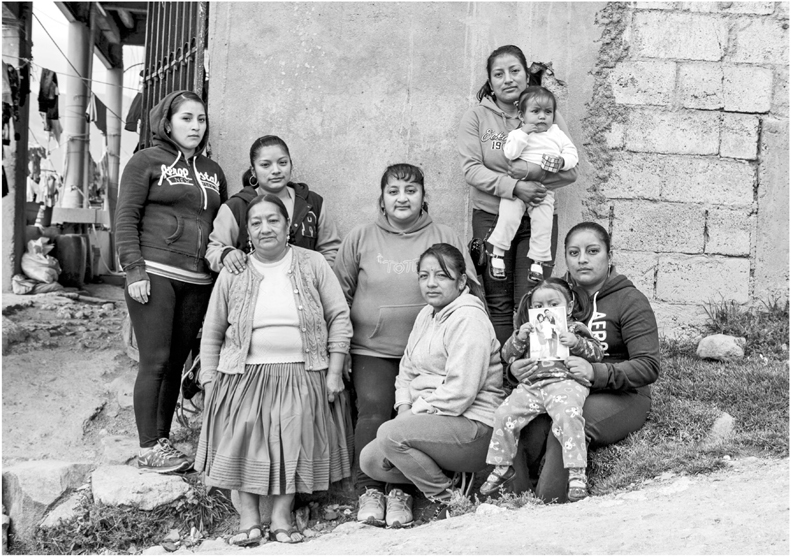

“Esperando por José.” Photo by Michael Wells.

For families like José’s, having no corpse means that they will always maintain hope that he is alive. They will always grieve for him. But the absence of physical evidence of his demise prevents them from publicly mourning. They can’t “tear at their clothes and hair, improvising various mourning laments to make the loss that has occurred public and utterable,”12 because they themselves aren’t sure what has been lost. The ambiguity of this situation means they cannot gradually move away from death.13 Desert necroviolence for them is both ethereal and inescapable.

José’s sister sits alone in his room (or is it a cenotaph?), clutching his clothes and praying that he will come back. His grandmother wanders off late at night to look for him down at the dusty soccer field in hopes of catching him drinking beers with his hooligan friends. His aunt avoids eating at his favorite restaurant, because she can’t bear to see the empty booth that he once routinely occupied. Like the souls of West African migrants who go missing during their crossing of the Sahara or the Mediterranean,14 José’s troubled spirit hovers above his family and visits them in their sleep. His Aunt Lucia tells me about dreams and visions that family members have of him: “I had a dream that he was near a river and that he was sitting down wearing a white shirt. He is picking up tiny pebbles and throwing them into the water. When I see him I ask, ‘What are you doing here?’ He says, ‘Nothing,’ and then just keeps throwing rocks. In another dream he tells me, ‘They didn’t come for me. I am still here in Nogales.’ I don’t know why I have these dreams. My dad has dreams where José is scared and asking him for help.” Others imagine that he has amnesia, is working for the mafia as a drug mule, or is being held hostage on a ranch. Sitting in her dark, windowless kitchen in Cuenca, his Aunt Paola sums up these frustrations and draws a stark contrast to the suffering experienced by Maricela’s family:

Paola: More than anything we just want to get to the bottom of this. To see what happened to him. God give us strength to accept whatever comes. Is he alive or is he dead? We need to finally know something about what has become of him. Imagine not knowing anything. [crying] We ask God to give us strength to keep moving forward. Maybe he is alive. God, send him back or have him turn himself into immigration or the police. We need to know so that we can keep moving forward as before. God willing, José will soon appear. Whether he is alive or dead, we just want to know. We want to no longer have doubts about where he could be or how he is or what happened to him. We don’t know anything . . . Maybe the coyote did something. Maybe he killed him and buried him so that no one would find him. If he was left behind, they should have found him dead, but they didn’t find anything. Sometimes these are the thoughts we have out of the desperation from not knowing. I don’t mean to sound ugly, but at least Maricela’s family knows that she is dead and they can put her in a tomb and visit her! At least their family can leave her flowers. ¡Aquí no sabemos nada! We know nothing about what happened to his life.

While his family ponders a million scenarios about where he is and what has become of him, his girlfriend, Tamara, just holds onto hope. As Mike and I sit across from her in a café in Cuenca, we are both struck by her optimism and strength. She is young, but she has the resolve of someone who has known pain beyond her years. For over an hour she tells us the story of how they met and fell in love. She also describes the pain of watching José leave. Despite the heavy sorrow in her words, she refuses to cry. Both of her parents have migrated to New York, and she lives alone with her older sister, with whom she constantly fights. She tells us that José is her best friend and the only one who understands her loneliness and pain. They are two teenagers struggling to make sense of lives forever fractured by transnational migration. They are kindred spirits. In a brightly lit coffee shop in Cuenca she holds back her tears when she tells me, “Right before he left, we told each other that no matter what happens, we would always be together. I have no idea if he is alive or dead, but I am always going to wait for him.”

“WE WILL WAIT UNTIL YOU GET HERE”

If you have never watched your own children starve, never struggled to provide medical care for your sick baby or gone years without hugging your son, it might be easy to blame José’s parents for what happened to him. After all, they were the ones who abandoned him in Cuenca and the ones who paid a smuggler to take their fifteen-year-old son into the desert. But placing all of the blame on his parents requires turning a blind eye to the global political economic structure that set this entire scenario in motion. How desperate must one be to leave five children behind and accrue thousands of dollars of debt to undertake a dangerous trip with no guarantees one will survive, much less succeed in getting across the border? Success in this case means finding yourself occupying a position in US society where your labor is always exploited and your social position precarious. How desperate must a parent be to see his son that he would entrust him to the hands of smugglers who will run him through a desert gauntlet where, by strategic design, suffering and death are likely outcomes? These are questions that many of the relatively well-off people who read this book will never be able to answer. Rather than blaming or judging José’s family, perhaps we can attempt to put ourselves in their position and try to imagine what life must be like when these are the types of decisions one must make.

As I sit in the living room of José’s parents’ house in New York, it’s hard to think about immigration statistics, legalities, the hybrid collectif, or whom to blame for what has come to pass. As Gustavo describes his final conversation with his son, there are no politics, just pain:

Gustavo: It was a Saturday when he called and said, “Papi, I’m on my way to be with you. The guides are coming for me and they are going to take me to you.” They left on a Saturday at 11 at night. After that day we don’t really know what happened to him. A week went by, and then two weeks went by. We still didn’t know anything about where he was. I called the guía, and he said that there was no way to communicate with José in the desert. I kept asking, “When is he going to arrive?” One Sunday morning we got a call from one of his cousins who got caught. They told me that José had escaped. I said that it seemed unlikely that he would have gotten away. They said, “It’s not true; José got away.” It’s not that easy to get away from immigration. I called the guide again and asked about my son. I said that if he got away, then he should know where he is. The guide started to give me different excuses about where José was. I never heard from my son again.

That Saturday was the last time I spoke to him. Before he left, he said to me, “I am full of hope. You have to have faith that we are going to be together.” He wanted me to support him. He said, “Promise me that you are going to help me when I get there.” I said to him, “You are my son. I will support you any way that I can. Don’t be afraid.” “Are you sure that you are going to be there for me?” he asked. I told him, “I promise that I am going to be here for you.” He was afraid. He had something he wanted to tell me. He was coming here with something on his mind. The last time I spoke to him, he said, “Papi, I really want to talk to you.” I said “OK, let’s talk.” “Not like this,” he said. “I want to talk face to face. Like father and son.” “OK,” I told him, “we will wait until you get here, or if you want to tell me right now, go ahead and tell me.” He said, “No, it’s not the time to talk about it yet. When I get there, we can talk.”

He never said what he wanted to talk about. [Paulina starts crying.] . . . He met a girl in Ecuador and they went out for six months. They were together about two weeks before he left, and this girl got pregnant. He found out while he was in Mexico. I guess this is what he wanted to tell me. He wanted to tell me that this girl was pregnant, and he wanted to know if I would help him. I didn’t get to tell him, but to this day I am going to support her and the baby girl she is going to have. I am not going to abandon her. This is the remorse that I have, that I could never tell him face to face that I was really going to support him. It’s going to be a girl and it makes me very happy. We have had such sadness since he disapeared. This child that is coming is going to bring happiness into our lives. It gives me hope to keep fighting for José.

His girlfriend calls me every day to see if I have any news about him. To see if we know anything. To see if I have spoken to anyone. I say, “No, there is nothing.” It is difficult to say that we have found nothing. She thinks I’m not doing anything here. That we aren’t calling anyone and that José is lost and we are just sitting here. That’s not true. We are trying to find any person that might know something about José. There is nothing that we can do to get back that joy that we lost until we find him. To know something about what happened to him.

There is nothing we can do. We can’t go down to the line and look for him. To lose him like this and not know what happened is going to make us cry for the rest of our lives. He was a very strong young man. [cries] I miss him so much. Sometimes I just want to take everything I own and throw it all away. In these moments I can’t let the things I am feeling explode out of me. I have to bottle up all of this pain that I hold inside. It’s hard. It’s hard because when I leave the house, it’s just him that I think about. There is no one else. When I’m at work, I try to concentrate on the things I need to do, but it only lasts for a little while. I am only thinking about him. I say to him, “What happened to you? Where are you? Why don’t you call me? You are strong.” He was a really strong young man.

Truthfully, I don’t really sleep. Normally I’m up until 2 or 3 in the morning. Then I get up at 4 or 5. I can’t sleep, because he is always in my dreams. [voice cracks] I can’t sleep. I have a photo of him that I always look at. I talk to him in the photo. We talk and I remember when he was a child. It makes me smile, but at the same time the tears come for the many things I haven’t been able to do for him.

We decided to bring José here, but we never thought that he would go missing. Never. We never imagined that this would happen like this, but now in reality this is happening to us. It’s hard to say that my son is missing and he is never coming back. I have faith that he will return and I will see him again. I don’t know how or in what form, but I want to see him. It’s OK if somebody says to me, “You know what, we found your son and he is like this or like this.”15 I just don’t want to live with doubt about what happened to him. God has given us the gift of a grandchild, but at the same time I am sad that we can’t find her dad. That we can’t find our son.

Every day that passes we feel more and more out of control. Sometimes it feels as if I am losing the battle. I try to wake up with energy some days and say, “We are going to find him. We are going to find him.” It is difficult to live like this. To know nothing, nothing, nothing. [crying] I pray to God that we will somehow be reunited with José in some form or another.

María José came kicking and screaming into the world in November 2013.