The first subscription list of 101 well-fleeced London names gathered by ‘Auditor Smythe’ for ‘the voiag to the Easte Indes’, on 22 September 1599, two days before the first public meeting at the Founder’s Hall, Moorgate Fields.

Sir Thomas ‘Auditor’ Smythe, the founder of the East India Company, in 1616.

Sir James Lancaster, who commanded the Company’s first voyage in 1601, shown five years earlier, on his return from his first disastrous journey east.

Sir Thomas Roe, the ambassador of James I who led Britain’s first official diplomatic mission to India in 1615.

Jahangir as the Millennial Sultan Preferring the Company of Sufis, by Bichitr. Jahangir is sitting enthroned with the halo of majesty glowing so brightly behind him that one of the putti has to shield his eyes from his radiance; another pair of putti are writing a banner reading ‘Allah-o Akbar! Oh king, may your age endure a thousand years!’ The Emperor turns to hand a Quran to a sufi, spurning the outstretched hands of the Ottoman Sultan. James I, meanwhile, is relegated to the bottom corner of the frame, below Jahangir’s feet, and only just above Bichitr’s own self-portrait. The King shown in a three-quarter profile – an angle reserved in Mughal miniatures for the minor characters – with a look of vinegary sullenness on his face at his lowly place in the Mughal hierarchy.

New East India House, the East India Company headquarters in London’s Leadenhall Street, after its early eighteenth-century Palladian facelift. A Portuguese traveller noted in 1731 that it was ‘lately magnificently built, with a stone front to the street; but the front being very narrow, does not make an appearance in any way answerable to the grandeur of the house within’. Like so much about the power of the East India Company, the modest appearance of East India House was deeply deceptive.

East India Company ships at Deptford, 1660.

Headquarters of the Dutch East India Company at Hughli by Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665.

Fort William, Calcutta, by George Lambert and Samuel Scott, 1731.

The severe and puritanical Mughal Emperor Alamgir Aurangzeb, whose overly ambitious conquest of the Deccan first brought Mughal dominions to their widest extent, then led to the eventual collapse of the Empire, painted c. 1653.

Below is his nemesis, the Maratha warlord Shivaji Bhonsle, shown at the end of his life c. 1680. Shivaji built forts, created a navy and raided deep into Mughal territory. He was crowned Chhatrapati, or Lord of the Umbrella, at two successive coronation ceremonies at his remote stronghold of Raigad in 1674.

The Persian warlord Nader Shah was the son of a humble shepherd and furrier. He rose rapidly in the Safavid army due to his remarkable military talents, before deciding to take over the Kingdom and then ‘pluck some golden feathers from the Mughal peacock’.

Nader Shah with the effete aesthete Emperor Muhammad Shah Rangila, whom the Persian relieved of his entire treasury, including the Peacock Throne, into which was embedded the great Koh-i-Noor diamond. The sudden impoverishment of Delhi after Nader’s departure meant that the administrative and military salaries could no longer be paid, and, without fuel, the fire went out of the boiler house of Empire.

A Mughal prince, probably the young Shah Alam, on the terrace of the Red Fort being entertained by dancing girls, c. 1739, around the time of Nader’s Shah invasion.

Aerial view down over the Red Fort, c. 1770.

A Leisurely Ride, by Nainsukh. In the aftermath of the fall of Mughal Delhi, the imperial artists fanned out across the Empire, and elegant masterpieces such as this began to be painted in courts as remote as Guler and Jasrota in the Himalayan foothills.

Europeans Besiege a City. As Mughal authority disintegrated, everyone took measures for their own protection and India became a decentralised and disjointed but profoundly militarised society. European mercenaries were much in demand for their military skills, especially as artillerymen.

A scene at a Murshidabad shrine.

Above the Hughli near Murshidabad.

The palaces of Faizabad.

Aliverdi Khan came to power in 1740 in Bengal in a military coup financed by the powerful Jagat Seth bankers. A catloving epicure who loved to fill his evenings with good food, books and stories, after defeating the Marathas he created in Murshidabad a stable political, economic and political centre which was a rare island of prosperity amid the anarchy of Mughal decline.

Above, Aliverdi Khan is shown hawking, and below, a little older, he awards a turban jewel, or sarpeche, the Mughal badge of office, to his nephew, while his grandson, Siraj ud-Daula, looks on.

Left and right: Siraj ud-Daula with his women. ‘This prince made a sport of sacrificing to his lust almost every person of either sex to which he took a fancy,’ wrote his cousin, the historian Ghulam Hussain Khan.

Aliverdi’s son-in-law, Shahmat Jang, enjoys an intimate musical performance by a troupe of hereditary musicians, or kalawants, from Delhi. These were clearly regarded as prize acquisitions because they are all named and distinctively portrayed. Seated waiting to sing on the other side of the hall are four exquisitely beautiful Delhi courtesans, again all individually named.

Siraj ud-Daula rides off to war.

The brilliant historian Ghulam Hussain Khan. The Nawab’s cousin was among the many who emigrated from the ruined streets of Delhi at this time. His Seir Mutaqherin, or Review of Modern Times, his great history of eighteenth-century India, is by far the most revealing Indian source for the period.

Robert Clive in command at the Battle of Plassey, 1757.

Mir Jafar Khan was an uneducated Arab soldier of fortune who had played his part in many of Aliverdi’s most crucial victories against the Marathas, and led the successful attack on Calcutta for Siraj ud-Daula in 1756. He joined the conspiracy hatched by the Jagat Seths to replace Siraj ud-Daula, and found himself the puppet ruler of Bengal at the whim of the East India Company. Robert Clive rightly described him as ‘a prince of little capacity’.

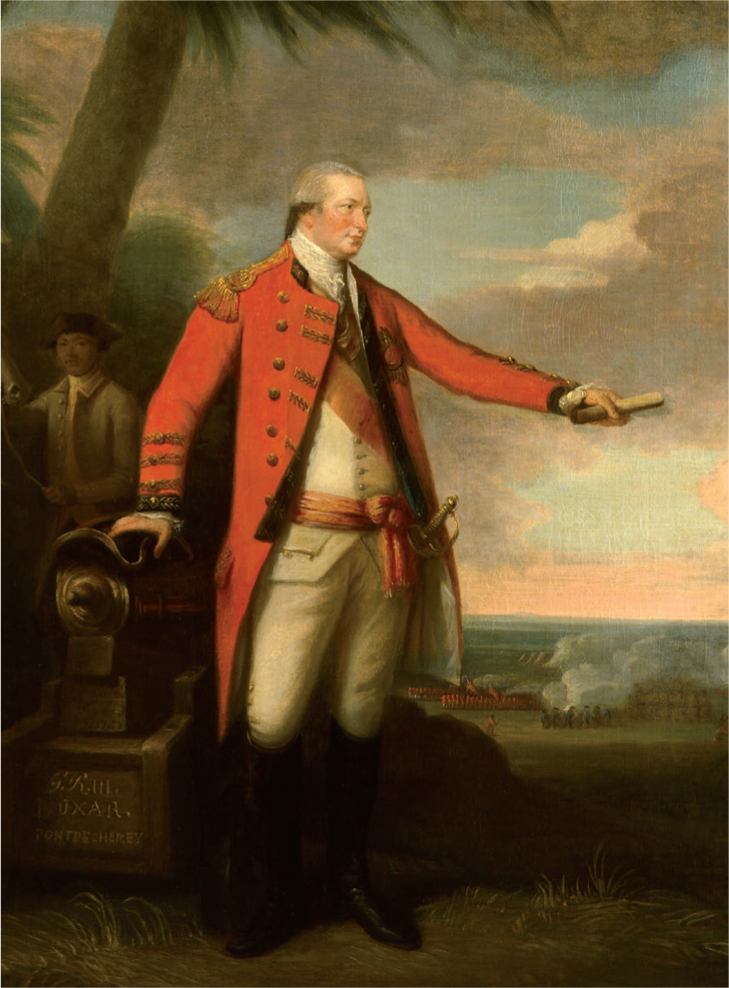

The young Robert Clive, c. 1764, one year before Buxar. Laconic, but fiercely ambitious and unusually forceful, he was a violent but extremely capable leader of the Company and its military forces in India. He had a streetfighter’s eye for sizing up an opponent, a talent at seizing the opportunities presented by happenchance and a willingness to take great risks.

Shah Alam, seated on a throne overlooking the Ganges, shortly after his proclamation as Emperor in 1759. Shah Alam had no land and no money, but compensated as best he could for this with his immense charm, poetic temperament and refined manners. In this way he managed to collect around him some 20,000 followers and unemployed soldiers of fortune, most of them as penniless and ill-equipped as he was.

Mir Jafar and his son Miran on a hunting expedition. As Mir Jafar stumbled and as his treasury emptied, his vigorous but violent son Miran turned increasingly vicious. ‘His inclination was to oppress and torment people,’ wrote Ghulam Hussain Khan, who knew him well. ‘He was expeditious and quick-minded in slaughtering people, having a peculiar knack at such matters, and looking upon every infamous or atrocious deed as an act of prudence and foresight.’

Mir Jafar (above) and Mir Qasim (right) in 1765. Mir Qasim was as different a man as could be imagined from his chaotic and uneducated father-in-law, Mir Jafar. Of noble Persian extraction, though born on his father’s estates near Patna, Mir Qasim was small in frame, with little military experience, but young, capable, intelligent and, above all, determined. He conspired with the Company to replace Mir Jafar in a coup in 1760 and succeeded in creating a tightly run state with a modern infantry army. But within three years he ended up coming into conflict with the Company.

Khoja Gregory was an Isfahani Armenian to whom Mir Qasim gave the title Gurghin Khan, or the Wolf. Ghulam Hussain Khan thought him a remarkable man: ‘Above ordinary size, strongly built, with a very fair complexion, an aquiline nose and large black eyes, full of fire.’

Official in Discussion with a Nawab – probably William Fullarton and Mir Qasim, Patna, 1760–65. Fullarton was a popular Scottish surgeon and aesthete and one of very few to survive the Patna massacre. He was saved by the personal intervention of his old friend, the historian Ghulam Hussain Khan.

A Palladian house and garden by the Bengali artist Shaikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya.

The Shaikh’s view of Government House and Esplanade Road, Calcutta, from the Maidan. Both seem to have been painted around 1827.

As the Mughal capital collapsed into anarchy, the celebrated Delhi artists Dip Chand and Nidha Mal migrated eastwards to find work in the richer, more stable and cosmopolitan courts of Patna and Lucknow. Here they developed a regional style, with the wide expanse of the Ganges invariably running smoothly between white sandbanks, as boats ply the waterways. Above: The cultured, Patna-based Kashmiri merchant prince Ashraf Ali Khan and his bibi Muttubby experiment with European fashions. Ashraf perches cross-legged on a Regency chair and both of them rest their hookahs on wooden teapoys. Below, Nawab Shuja ud-Daula passes in a grand procession past a line of riverside palaces.

After Buxar, Europeans and their sepoy guards fanned out across India, trading, fighting, taxing and administering the revenues and justice departments. Above: Captain (later Colonel) James Tod rides an elephant, by Chokha, Mewar, 1817.

Hector Munro, c. 1785. Munro was the victor of Buxar and the vanquished at Pollilur.

Madras sepoys, c. 1780.

British Officer in a Palanquin, by Yellapah of Vellore.

A Military Officer of the East India Company, Murshidabad, 1765.

Robert Clive by Nathaniel Dance, c. 1770. Here Baron Clive of Plassey is shown in portly middle age, very much the man aware of all that he had achieved to establish the political and military supremacy of the East India Company in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. ‘Fortune seems determined to accompany me to the last,’ Clive wrote to his friend and biographer Robert Orme. ‘Every object, every sanguine wish is upon the point of being completely fulfilled.’

The young Warren Hastings by Tilly Kettle, c. 1772. A thin, plainly dressed and balding young man in simple brown fustian with an open face and somewhat wistful expression, but with a hint of sense of humour in the set of his lips. His letters at this period reveal a diffident, austere, sensitive and self-contained young man who rose at dawn, had a cold bath then rode for an hour, occasionally with a hawk on his arm. He seems to have kept his own company, drinking ‘but little wine’ and spending his evenings reading, strumming a guitar and working on his Persian.

Shah Alam Conveying the Gift of the Diwani to Lord Clive, by Benjamin West.

Today we would call this an act of involuntary privatisation. The scroll is an order by the Emperor to dismiss the Mughal revenue officials in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and replace them with a set of English traders appointed by Clive – the new Governor of Bengal – and the directors of the Company, whom the document describes as ‘the high and mighty, the noblest of exalted nobles, the chief of illustrious warriors, our faithful servants the English Company’. The collecting of Mughal taxes was henceforth subcontracted to a multinational corporation – whose revenue-collecting operations were protected by its own private army.

The Mughal Emperor Shah Alam Reviewing the Troops of the East India Company at Allahabad With General Barker, by Tilly Kettle. In 1771, Barker was despatched to Allahabad to try and stop Shah Alam returning to Delhi but found him ‘deaf to all arguments’. The Emperor had long found life in Allahabad as a puppet of the Company insupportable, and now he yearned to return home, whatever the risks.

Shuja ud-Daula, Nawab of Avadh, with four Sons, General Barker and Military Officers, by Tilly Kettle. Shuja ud-Daula was a giant of a man. Nearly seven feet tall, with prominent, oiled moustaches, he was a man of immense physical strength. Even in late middle age he was reputedly strong enough to lift up two of his officers, one in each hand. He was defeated by the Company at the Battle of Buxar in 1765 and replaced by Clive back on the throne of Avadh, where he ruled until the end of his life as a close ally of the EIC.

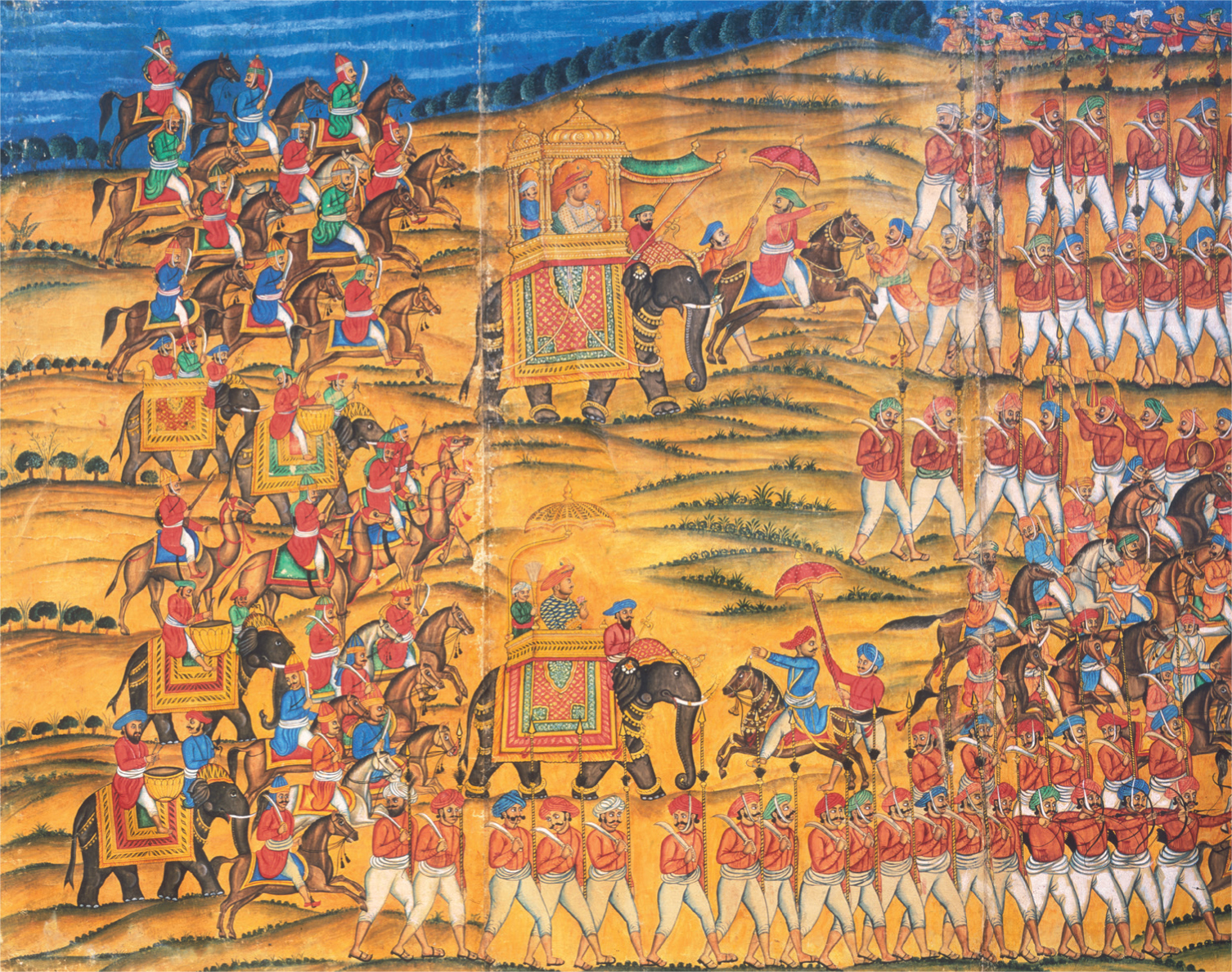

The royal procession of Shah Alam as the Emperor returns to Delhi in 1771. A long column of troops snakes in wide meanders along the banks of the Yamuna, through a fertile landscape. At the front of the procession are the musicians. Then follow the macemen and the bearers of Mughal insignia. Next comes the Emperor himself, high on his elephant and hedged around by a bodyguard. The imperial princes are next, followed by the many women of the imperial harem in their palanquins and covered carriages; then the heavy siege guns, dragged by foursomes of elephants. Behind, the main body of the army stretches off as far as the eye can see.

Nana Phadnavis, the Pune-based statesman and minister to the Peshwas, known as ‘the Maratha Machiavelli’. He was one of the first to realise that the East India Company posed an existential threat to India and tried to organise a Triple Alliance with the Hyderabadis and the Sultans of Mysore to drive them out, but failed to carry the project through to its conclusion.

Sepoys of the Madras Infantry, by Yellapah of Vellore.

The Battle of Pollilur. A copy of the mural Tipu Sultan had painted on the walls of his garden palace, Darya Daulat Bagh, commemorating his greatest victory in 1780. At the centre, Colonel William Baillie can be seen in his palanquin, touching his finger to his mouth in astonishment as Tipu blows up his ammunition wagon and the Mysore cavalry assault the Company square on all sides.

Edmund Burke, from the studio of Sir Joshua Reynolds. Burke was an Anglo-Irish Whig statesman and political theorist. He had never been to India, but part of his family had been ruined by unwise speculation in East India stock. Together Burke and Francis worked on a series of Select Committee reports exposing the Company’s misdeeds in India. Before he met Philip Francis, Burke had described himself as ‘a great admirer’ of Hastings’ talents. Francis quickly worked to change that. By April 1782, Francis had drawn up a list of twenty-two charges against Hastings, which Burke then brought to the House. After five years of obsessive campaigning, Burke and Francis persuaded Parliament that there was enough evidence to impeach him.

Philip Francis by James Lonsdale, c. 1806. Wrongly convinced that Hastings was the source of all corruption in Bengal, and ambitious to replace him as Governor General, Francis pursued Hastings from 1774 until his death. Having failed to kill Hastings in a duel, and instead receiving a pistol ball in his own ribs, he returned to London, where his accusations eventually led to the impeachment of both Hastings and his Chief Justice, Elijah Impey. Both were ultimately acquitted.

Portrait of the elderly Warren Hastings by Lemuel Francis Abbott, 1796. Far from being an ostentatious and loud-mouthed new-rich ‘Nabob’, Hastings was a dignified, intellectual and somewhat austere figure. Standing gaunt at the bar during his impeachment in his plain black frock coat, white stockings and grey hair, he looks more Puritan minister about to give a sermon than some paunchy plunderer. Nearly six feet tall, he weighed less than eight stone: ‘of spare habit, very bald, with a countenance placid and thoughtful, but when animated, full of intelligence.’

The Impeachment of Warren Hastings in Westminster Hall, 1788. This was not just the greatest political spectacle in the age of George III, it was the nearest the British ever got to putting the Company’s Indian Empire on trial. Tickets for the few seats reserved for spectators changed hands for as much as £50, and even then so many people wished to attend that, as one of the managers of the impeachment noted, the audience ‘will have to mob it at the door till nine, when the doors open, and then there will be a rush as there is at the pit of the Playhouse when Garrick plays King Lear’.

Mahadji Scindia in Delhi Entertaining a British Naval Officer and a Young British Military Officer with a Nautch, c. 1790.

Qudsia Bagh palace where Ghulam Qadir was brought up during his time at the court of Shah Alam.

The blind Shah Alam II on a wooden replica of the Peacock Throne, c. 1790, by Khairullah. Now in his seventies, the old king sat amid his ruined palace, the sightless ruler of a largely illusory empire.

Tipu Sultan on his elephant commanding his forces at the Battle of Pollilur.

Lord Cornwallis receiving the sons of Tipu Sultan after his 1792 invasion of Mysore, by Mather Brown.

Tipu succeeded his father in 1782 and ruled with great efficiency and imagination during peace, but with great brutality in war. He was forced to cede half his kingdom to Lord Cornwallis’s Triple Alliance with the Marathas and Hyderabadis in 1792 and was finally defeated and killed by Lord Wellesley in 1799.

A View of the East India Docks, c. 1808 by William Daniell, seen from what is now East India Dock, London.

In less than fifty years since the 1750s the Company had seized control of almost all of what had once been Mughal India and encircled the globe. It had also created a sophisticated administration and civil service, built much of London’s docklands and come close to generating nearly half of Britain’s trade. Its annual spending within Britain alone – around £8.5 million – equalled about a quarter of total British government annual expenditure. No wonder, then, that the Company now referred to itself as ‘the grandest society of merchants in the Universe’.

The Scindias

Mahadji Scindia was a shrewd Maratha politician who took Shah Alam under his wing from 1771 onwards and turned the Mughals into Maratha puppets. He created a powerful modern army under the Savoyard General Benoît de Boigne, but towards the end of his life his rivalry with Tukoji Holkar and his unilateral peace with the East India Company at the Treaty of Salbai both did much do undermine Maratha unity.

When Mahadji Scindia died in 1794, his successor, Daulat Rao, was only fifteen. The boy inherited the magnificent army that Benoît de Boigne had trained up for his predecessor, but he showed little vision or talent in its deployment. His rivalry with the Holkars and failure to present a common front against the East India Company led to the disastrous Second Anglo-Maratha war of 1803. This left the East India Company the paramount power in India and paved the way for the British Raj.

The Wellesleys

Richard Wellesley conquered more of India than Napoleon did of Europe. Despising the mercantile spirit of the East India Company, he used its armies and resources successfully to wage the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, which ended with the killing of Tipu Sultan and the destruction of his capital in 1799, then the Second Anglo-Maratha War, which led to the defeat of the armies of both Scindia and Holkar, 1803. By this time he had expelled the last French units from India and given the East India Company control of most of the subcontinent south of the Punjab.

Arthur Wellesley was fast promoted by his elder brother to be Governor of Mysore and ‘Chief Political and Military Officer in the Deccan and Southern Maratha Country’. He helped defeat the armies of Tipu in 1799 and those of the Marathas in 1803, most notably at the Battle of Assaye. Later famous as the Duke of Wellington.

The Duke of Wellington on Campaign in the Deccan, 1803. After the Battle of Assaye one of Wellesley’s senior officers wrote: ‘I hope you will not have occasion to purchase any more victories at such a high price.’

Two armies drawn up in combat, with artillery in front, cavalry in the wings and elephants bringing up the rear.