For several hours, the staff worked hard upon the details of the move and the alteration in orders made necessary by this sudden change of plan. There was much hurried coming and going in the château, much ringing of telephone bells, and purring of dispatch riders’ motor-cycles outside in the darkness. Dawn was near before the last order was written and sent off; but already the move-table had come into operation, and the veteran division in fighting kit, like a pefectly adjusted machine, had begun its retreat.

The château was soon almost deserted. The Headquarters staff packed up and went back. Bretherton told them that he would remain with the rear party for a time and rejoin Headquarters later. His intention was to remain in the château till it was captured by the advancing British vanguard. Reports reached him that the rear party were in touch with that vanguard, and he pictured it, Gurney and the men of his old company, in the early-morning light feeling their way forward in the way in which he himself had taught them.

A machine-gun unit of the rearguard arrived and began to fortify the château. Bretherton found a gun team in an ante-room overlooking the courtyard. They had propped mattresses against the window and were mounting the gun. But he sent them away; the château, he said, was not to be turned into a strong-point. And the machine-gun team departed to take up another position in the surrounding woods.

At last he could relax. He had but to wait for the British vanguard. He sat alone in the G.O.C.’s room, huddled in an armchair, worn out from lack of sleep and by the hours of heavy strain he had undergone. His face was ashen in the dim light of the guttering candles.

He rose wearily to his feet and threw open the shutters. The strong morning light flooded through the windows, dispersing the shadows in the corners of the big room and disclosing the burnt-out fire in the huge grate, the big map upon the silk-hung walls, the long low chesterfield, the dark polished wood of the grand piano, and the two or three small tables on the thick carpet.

On one of these, a packet addressed to General von Wahnheim caught his eye. The typewritten sheets it contained proved to be Hubbard’s dossier which Captain Trierforchten had promised to send him. He dropped back into a chair and began to read. And as he read, scenes with the old company and battalion rose vividly in his memory and took on a new significance: Private Christmas standing red-faced in the little company orderly room whilst poor Melford read aloud the letter in answer to the advertisement of a “lonely soldier”; Hubbard superintending Private Christmas carrying out his sentence of answering all those letters; Hubbard with a pile of coins before him playing nap in the Motor Machine-gun mess; Melford hunting for the map that disappeared when the aeroplanes bombed Sericourt; himself under arrest in connection with that photograph in the newspaper; Hubbard with B Company in the little Somme valley when the missing map was discovered in an envelope bearing the battalion censor stamp. And many things that had formerly puzzled him were clear now.

The document was a brief record of Hubbard’s activities from the German point of view. The German secret agent No. 304, a woman, made a practice of answering advertisements by soldiers. One reply she had received, not from a lonely soldier, but from his officer, Hubbard. Correspondence of a harmless nature was carried on between them, in the course of which she learned that Hubbard gambled and was usually very short of money. A photograph he sent her of a British officer outside a café she sold to a paper and sent him the proceeds augmented by German money. He was pleased with this, and other photographs followed, though none of any great military value. All of these she pretended to sell to newspapers and forwarded to him the money she pretended to receive for them.

When on leave, he met her and was introduced to an invalid uncle, who, being unable to move about or read, liked returned soldiers to tell him about the war. Hubbard indulged the old man’s weakness, and in return was helped out of his financial difficulties. One or two maps and several photographs were sent to her from time to time and were paid for by the interested uncle. The fiction that this correspondence was harmless was still kept up, though he must have known by this time that she was an enemy agent. The letters were sent to various poste-restante addresses.

Eventually Hubbard was captured in the great German drive of 1918, and in the hope of being set at liberty or of receiving better treatment, he declared himself to be a German agent. This statement was verified, but the German authorities had not sufficient confidence in the man to send him back across the lines, and they used him on odd jobs and occasionally put him in prisoner-of-war camps to report the conversation of prisoners.

Bretherton put down the document with a grimace. A sordid story, he thought. The man had run true to type. He had the guts to be neither a good patriot nor a good traitor. And he had ended up on the losing side; had done more harm to himself than to his country.

Among the papers were several photographic negatives, but that which most interested Bretherton was one of himself outside the café at Ruilly. He held it up to the light, with a wry smile. That negative had caused him much trouble in those old days with the old company—those good old days. He dropped the negative on the table with a sigh and walked to the window.

Desultory rifle and machine-gun fire sounded from the distance, and from time to time the woods echoed with the staccato reports of a battery of German field guns that had taken up a position among the trees in rear of the château. The tide of war was moving steadily forward, and Bretherton, by the window, knew that it could not be long before khaki figures broke cover from among the trees.

But the knowledge caused no answering flutter of his pulses. The fatigue and strain of the long sleepless hours weighed heavily upon him. He was oppressed by a sense of the complicated hopelessness of war, of the futility of everything. Painful images flitted through his tired brain: Hubbard’s mean treachery; his own desertion of the Duchess Sonia, for whom that part of him that was von Wahnheim still yearned; his killing of two men of A Company; his fighting for the enemy that were yet his friends; his betrayal of those men who trusted him. And he had not even gained the information for which G.H.Q. had sent him; he had accomplished nothing, except perfidy and bloodshed and misery for himself.

The sound of rifle fire had grown perceptibly nearer. The battery in the rear of the château had limbered up and moved back. In the woods, a new sound, like the ripping of calico followed by the bang of a dinner-gong, announced the approach of British field guns.

He had achieved nothing, except this avoidance of further bloodshed by moving the division back… that and… Helen.

The sound of a door closing softly behind him caused him to turn. At the far end of the room, in the shadow of the screen by the door, stood a woman in a long dark cloak. She advanced slowly across the threshold and threw open her cloak, revealing the white evening frock beneath. Bretherton caught his breath as the light from the long windows fell upon her face. There was no one he less desired to see at that particular moment.

He bowed low, to cover his embarrassment. “My dear Duchess,” he stammered, “what brings you here at such a time and in such clothes?”

She came forward, with a slow, shy smile and threw off her cloak. Glancing down at her evening frock, she answered: “As for this—well, you know my valiant effort to maintain some decency in this disgusting war. We dine respectably, though it be off a ration biscuit. But last evening we had sudden orders to move. Your dreadfully wise and grown-up plans had been changed all in a moment, and I had no time to change my frock. I was busy till dawn getting my patients away.”

Her face took on a sudden, serious expression, and she came close to him, looking earnestly into his face.

“I heard that you had been ill after you left me—that you had gone back for a rest. No one seemed to know where. And just as I finished packing off my damaged children this morning, I heard that you had returned and were here. At that moment Leo drove up in a car. And so…”—a faint colour tinged her cheeks—“and so after what… well, what did not happen because old General Ulrich interrupted us, I… I had to see you.”

Grey figures were moving among the trees around the château. From time to time, the crack of a rifle came from the upper part of the building, where a sniper had taken up his position behind a chimney.

Bretherton glanced despairingly around the room. “But you cannot stay here,” he cried. “The British are close at hand. Listen! That is one of their Lewis guns.” He placed a hand on her arm and tried to lead her to the door. He did not look at her.

She stopped him and, with a hand on either sleeve, gazed up into his face. “You are not angry with me for coming?”

He shook his head despairingly. She let go his sleeve and stood with the tips of her fingers resting on a little table.

“You make it very difficult for me… Otto,” she said.

He threw out his hands beseechingly. “I… I am only thinking of… of your safety,” he answered miserably.

She dismissed the fear with a little shrug of her bare shoulders.

“Do you remember,” she continued, “that you once said that you could never bring yourself to ask any woman; and that certainly no woman would ever ask you?”

He made a little movement of protest with his hands.

“And I answered,” she went on bravely, with cheeks aglow, “that I was almost tempted to ask you myself. Well… I…”

“And I,” he interrupted quickly, “said that as your friend, I could not allow you to place yourself in a position so dangerous and… and so undignified. Nor can I.”

Her head tilted quickly upwards, and a wave of colour swept over her face and neck.

He bowed stiffly before her anger. “I… I have been ill,” he said lamely.

The colour faded slowly from her cheeks, and her eyes assumed a more gentle expression. They searched his face. “Yes, yes; I know,” she said. “But you look changed—different. What is it?”

“Nothing… it is nothing. I have been ill; but nothing serious. Let us leave it at that.” His eyes met hers appealingly.

She gazed at him for a few moments in silence. “Yes, you are changed,” she said at last, slowly. “I understand.” Her voice cut like a knife. She laid a hand upon her cloak.

He threw out his hands protestingly. “I have been ill,” he repeated desperately. “I… I… you see, I suddenly recovered my memory. It was a shock… all my past life that I had forgotten… before the war… Berlin… everything.”

She dropped the cloak and was watching him with serious eyes.

He went on recklessly: “I remembered dining with you in Berlin… when you were a schoolgirl… and that Englishman, my double… Bretherton, he was there…” He laughed mirthlessly on a high-pitched note. “God, I’m becoming hysterical,” he thought.

She came round the table and held his arms firmly in her hands and gazed earnestly into his face. “You are different,” she murmured in a far-away voice. “Different.”

There was a puzzled expression in her eyes. He tried to draw away, but she held him firmly. Suddenly the expression in her eyes changed. The puzzlement disappeared and was replaced by a startled look. Her grip on his arms tightened and then relaxed. she backed slowly from him.

“You… you are not Otto von Wahnheim,” she cried in a low voice. Enlightenment was dawning in her face. “You”—breathlessly—“you… I know who you are… you are that Englishman… Bretherton.”

An aeroplane shot low overhead, with a sudden gust of sound.

He made a vague gesture with his hands. “I… I am von Wahnheim,” he managed at last.

“No.” She shook her head slowly, but with conviction.

“The only von Wahnheim you have ever known,” he persisted.

Her eyes did not leave his face. “Where is he… the real von Wahnheim?”

He abandoned the useless struggle. “He… he is dead.”

“You… killed him!” The words were scarcely audible.

“No, no. He was missing… killed on the Somme, long ago. You never met him except that once before the war, in Berlin.”

“Are you lying to me?” She was watching him intently with narrowed eyes.

“No. I swear it’s the truth; I swear.” His voice was earnest. “I knew him before the war; shared rooms with him in Berlin. I have not seen him since… nor have you. He was missing on the Somme. I was captured soon after, but escaped. I had a bad time… and… and my memory went. I thought I was von Wahnheim… and all that… Cologne… you know…”

She nodded. She was watching him intently, with ashen face. There was no longer doubt in her eyes.

“Then I was captured by my… the British; knocked on the head… near Arras. I came round in hospital and… remembered everything—myself, von Wahnheim…” He stopped.

“But you came back?”

He passed a hand wearily across his forehead. “Yes. On the way back I was shut in a box, in darkness… for days. And my memory went again. I was von Wahnheim. It came back suddenly, in the General’s car, after I left you… that look in your eyes. I was trying to remember where…” He stopped suddenly.

“Go on.” Her voice was low and commanding.

He remained silent.

“Go on. That look in my eyes,” she reminded him. “You were trying to remember where you had seen it… before?”

He nodded miserably.

“And you remembered? You had seen it before, then?” Her eyes compelled him to look at her. “In… some other woman’s eyes?”

He remained silent. She stamped her foot with sudden fury. “Tell me—tell me. You had seen it before, in the eyes of some English girl?”

The aeroplane shot back overhead with an echoing roar.

He nodded again, miserably. She was silent for a moment, and then demanded: “What did you do when you disappeared?—when you left the division?”

He did not reply.

“Did you go to… to your own people?”

He nodded.

She toyed with a folded map on the table. “And you came back… but not for me.” She looked at him again, and her eyes were hard. “So that is why the division suddenly retreats!”

He made a helpless gesture with his hands. “What was I to do?” he demanded. “It was only to prevent useless waste of life—I swear it. To save the lives of these men I commanded, and of my own countrymen over there.” He flung out a hand towards the window. “And you! What could I do? Good God, don’t you understand that I am two people? That I have the thoughts and feelings of two men—that even now that I am Bretherton, I know what von Wahnheim felt!” He seized her wrists and went on fiercely. “By God, you shall understand—understand that as von Wahnheim I loved you… and love you; but as Bretherton I…” He let fall her hands and turned away. “As Bretherton…”

She nodded slowly. “I understand.”

A tap sounded on the door. It opened, and Leo von Arnberg came in. As usual, he was immaculately dressed. He was in the fighting zone, but he wore no shrapnel helmet. The grey service cap, with its shiny black peak and plum-coloured band was set at a jaunty angle. He clicked his heels and saluted.

“I am sorry to intrude, sir,” he cried. “But we really ought to leave. Nearly everyone has gone. The British will be here in under half an hour, and they will be turning their guns on us presently. I have that man you wanted to see outside, sir, but there really is not time now. I am responsible for your safety, sir.”

The sound of a gigantic whip-lash whistled through the sky and was followed by an ear-splitting crack and a patter of falling stones on the roof. Leo von Arnberg smiled and bowed ironically towards the window.

The Duchess Sonia took up her cloak. “Come, Leo; I am ready,” she said. “General von Wahnheim is not coming—yet.”

“But really, sir…” began von Arnberg.

Half-way across the room, the Duchess paused and turned to Bretherton. She spoke in English. “Good-bye, Mr. Bretherton. May you be happy with your English Miss. One thing only I ask of you; do not tell her of me.”

Bretherton bowed low. She turned and swung the cloak over her shoulders. “I am ready, Leo.”

One of the window-panes flew into pieces with a loud report, and almost instantaneously was followed by the dull thud of metal striking a soft substance. Leo von Arnberg spun round like a Russian dancer and collapsed into the chair behind him.

The cloak slid from Sonia’s fingers, and she ran forward with a little cry. Von Arnberg’s face was drawn and ashen under the tan, but he forced a little smile to his pain-twisted lips. His hand was at his shoulder, and beneath the clutching fingers a damp brown stain was slowly spreading. He struggled into a sitting posture and grimaced.

“We must get him away from here,” cried Bretherton, and he ran to the door. At the end of the passage he saw a man in uniform. He called and beckoned to him and returned to von Arnberg. Sonia was trying to open her brother’s tunic, and the pain of the movement caused him to grip the arms of the chair till his knuckles showed white.

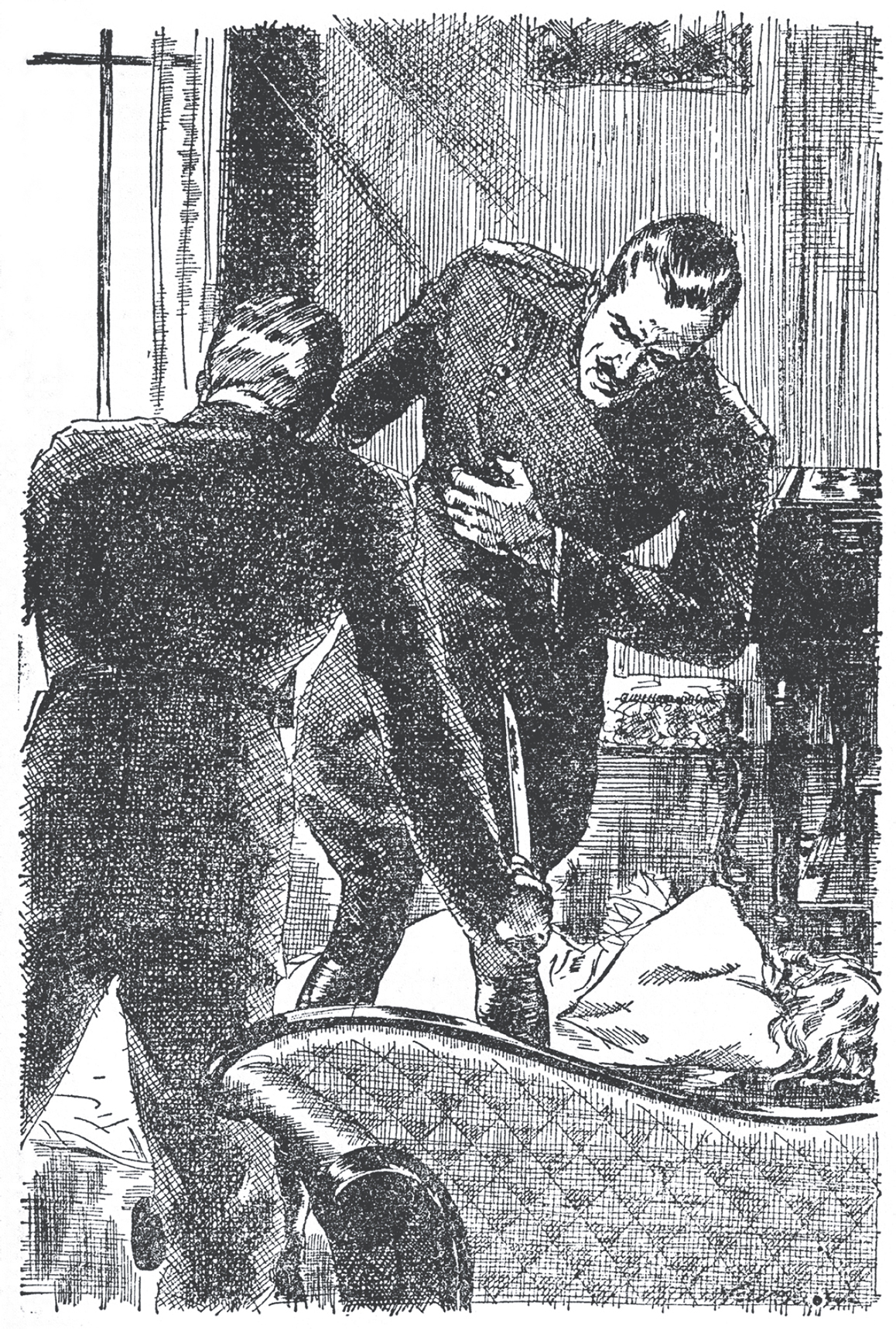

Bretherton dropped on one knee beside him. “We must slit the tunic,” he said, and felt in his pockets for a knife. He could not find one. Beside him he saw the legs and lower part of the body of the man he had called in.

“Give me your bayonet,” he cried, and when the man did not answer, he tapped the hanging scabbard without looking up. The man drew his bayonet. Bretherton stood up and put out his hand for it; and then, for the first time, looked at the man.

He stood for a second staring in surprise, with his hand outstretched for the bayonet that was held handle towards him. And then he clenched his fists and strode forward fiercely. “You swine! You dirty swine!” he cried.

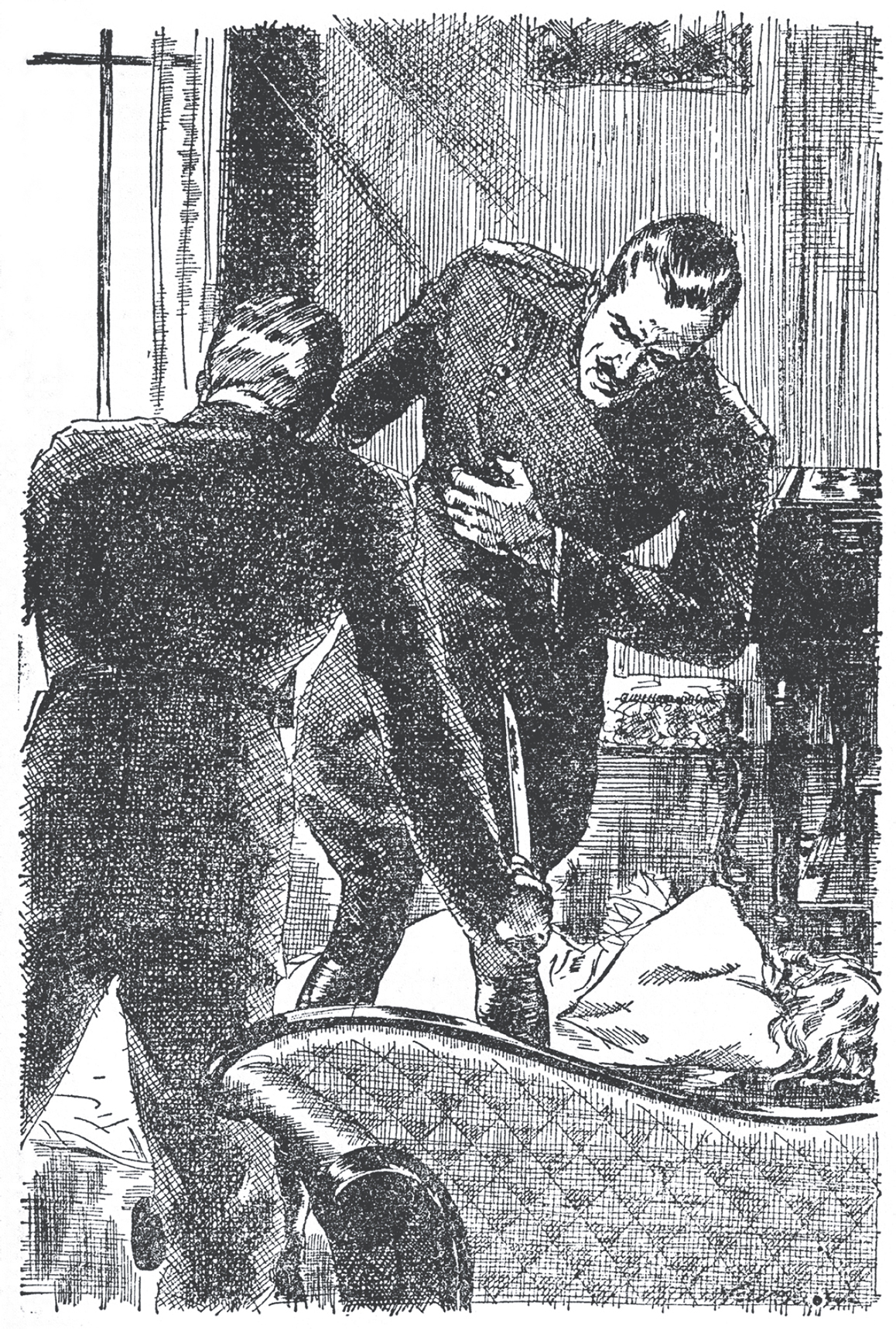

Hubbard backed from his accuser. Von Amberg uttered a warning cry as the bayonet point described a semi-circle. But Bretherton, in his wrath, still advanced. The glittering bayonet flickered unsteadily for a second and then swiftly drove forward.

Bretherton staggered back, bent suddenly double. He saw something white slide past him and heard a dull, heavy thud. The Duchess Sonia lay stretched upon the carpet. Von Arnberg rose painfully to his feet. Hubbard was no longer there.

Bretherton was on his knees, swaying, beside the Duchess. “Look to her, Leo… fainted,” he gasped.

Bretherton staggered back, bent suddenly double.

Painfully and laboriously, von Arnberg applied all the remedies he knew for syncope. Bretherton had his fingers on her pulse, but he could detect no movement.

“Get—get her to the sofa,” came his hoarse voice.

Slowly and painfully, the two wounded men lifted the girl and staggered to the sofa. Bretherton dropped back into a chair. His face was grey and he breathed with difficulty. Von Arnberg worked desperately to restore animation to the silent figure.

Minutes passed. The room was very quiet. Outside, the sounds of war were becoming louder. Painfully and with suppressed groans, Bretherton hoisted himself from the chair and laid a hand on Arnberg’s shoulder.

“It is… no good, Leo… no good. Save yourself… in time.”

Von Arnberg raised a face that was scarcely recognizable and stared stupidly at Bretherton. Bretherton shook him gently. “Hurry, Leo… hurry.”

Von Arnberg rose shakily to his feet. The meaning of the crack of rifles and the zip and plop of bullets outside penetrated his dulled senses. A bullet smacked into the wall opposite the windows.

“Come on, sir,” he gasped.

“No, no.” Bretherton shook his head. “I’m done, Leo. Leave me… while there is time.”

Von Arnberg hooked his arm round Bretherton and tried to raise him, but the pain was too much for his wounded shoulder, and he let go with a groan.

“Good-bye, Leo,” said Bretherton, and held out his hand.

Von Arnberg pressed it. “I will get help,” he said. “I will get you out of this, General.”

He turned and swayed across the room towards the door. And as he went, he fumbled with his pistol holster. “And I’ll get that swine!” he cried fiercely.

Half-way along the narrow passage that led to the side of the château, his legs gave way beneath him; the narrow space echoed to the crack of the pistol in his clutching fingers, and the bullet smacked harmlessly into the wall. He swayed and crashed senseless to the floor.

Among the trees that fronted the château, men were shouting. The sound of English voices came through the long, broken windows to Bretherton, sitting huddled and grey-faced in a chair. He opened his eyes and rose slowly to his feet. Painfully and falteringly, he moved towards the window; but on his way, his eyes encountered the piano, and he turned towards it. A twisted smile flickered for a moment across his face. It was months now since he had played. Inch by inch he neared the chair, grasped it, and lowered himself. His hands spread slowly over the keyboard.

The air he played was Helen’s little song, “Just a song at twilight.” His fingers moved falteringly but more surely as the tune and its associations gripped him. A burst of Lewis-gun fire ripped out in the woods and died away. The end of the war; the last lap. The tune changed to the old war air: “Après la guerre finie.” He played on painfully.

Another not-far-distant shout came through the windows. They were coming, the British vanguard, his old battalion… Gurney, Pagan, and the rest… coming. The tune changed to “Tipperary.” His strength was ebbing, and he had difficulty in seeing; but his fingers needed no eyes to guide them in that tune. He gathered all his strength and played the last chorus firmly and triumphantly:

It’s a long way to Tipperary,

It’s a long way to go.

It’s a long way to Tipperary

And the sweetest girl I know.

Good-bye, Piccadilly; farewell, Leicester Square,

It’s a long, long way to Tipperary,

But my heart’s right there.

The piano ceased. Darkness settled upon him. His leaden arms slid from the keyboard; his head fell forward till it rested upon the rack of the piano.

Somewhere in the silent château, a cautious footstep sounded. Outside, bayonets twinkled among the trees. A sudden rattling roll of Lewis-gun covering fire throbbed through the air. And then, on to the broad stretch of grass fronting the château straggled a line of khaki figures.