In 2014, Catherine Nichols, an aspiring novelist, undertook an experiment. She sent a query letter describing her unpublished novel to fifty literary agents under her own name, and then she sent the same letter to fifty agents under the name of “George Leyer” (wink).1 “George” had his manuscript accepted for review seventeen times, whereas Catherine had hers accepted only twice. Even the rejections that “George” received were warmer and more encouraging than those sent to Catherine. Similar workplace bias correlated with gender or race has been observed in the process of reviewing job applications.2 The surprising thing about the gender bias in the publishing business is that statistically nearly half of literary agents and more than half of editors at publishing houses are women.3 The fact that women might have hidden biases against other women might come as something of a surprise; the fact that men have discriminated against women since time immemorial is not a secret to anyone. So successful have men been in excluding women from “the genius club” that even women have come to downplay their own importance.

Recently, I surveyed more than four thousand adults, asking them to name a dozen geniuses in Western cultural history. My respondents were all students, 57 percent women and most over age fifty, enrolled in One Day University, a continuing education program operating in seventy-three U.S. cities. The aim of my survey was to determine how far down the list of geniuses we would go before landing upon a woman. Even among this strong female majority of respondents, the first woman emerged on average in eighth place. Those named most frequently were scientists Marie Curie and Rosalind Franklin, mathematician Ada Lovelace, and writers Virginia Woolf and Jane Austen, with Curie named most often by far. There were no female philosophers, architects, or engineers at all.

This same disproportion arose early on in my “genius course” at Yale. Although Yale undergraduates are now fifty-fifty by gender, and although the “genius course” is a general humanities class open to all, annually the enrollment skews about sixty-forty male-female. Students at Yale and elsewhere vote with their feet, and, despite favorable course evaluations, women at Yale don’t seem to be quite as interested in the notion of genius as their male counterparts. I have also noticed that when I pose a question or ask for a contrary opinion in class, predominantly male students respond. Once I realized this, I began asking a teaching assistant to keep track of the gender of each respondent and the amount of “airtime” consumed by each. The ratio, year after year, has been about seventy-thirty male to female.

Puzzled by this discrepancy, I soon found that others in the professional world, Sheryl Sandberg among them, had observed that in open discussion “alpha males” eagerly dominate, while women at first tacitly watch, sizing up how the game will be played.4 And a 2012 study by professors at Brigham Young University, Princeton University, and Portland State University reported that at academic conferences women spoke significantly less than their proportional representation—their airtime amounting to less than 75 percent of that of men.5 My initial 30 percent female engagement rate, however, was worse.

Speaking in public is one thing, but what was causing women to disengage from the subject matter I was teaching? Are women less excited by competitive comparisons that rank some people as “more exceptional” than others? Are they less likely to value the traditional markers of genius—things such as the world’s greatest painting or most revolutionary invention? Are women somehow less interested in the very concept of genius? If so, why might this be the case?

A clue was to be found in a 2010 research report issued by the American Association of University Women titled Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics.6 It emphasized that women have an uphill battle in STEM fields owing to the obvious stereotypes, biases, and unfavorable work environments in colleges and universities. Likewise, a 2018 report by Microsoft, “Why Do Girls Lose Interest in STEM?,” suggested that the lack of mentors and parental support play a role.7 I made the connection: fewer women probably opt for my “genius course” and fewer women embrace STEM fields because both have traditionally been constructed by and around men. Women have fewer role models (geniuses) to whom they can relate, and fewer contemporary mentors with whom they can bond. Why take a course in which the reading, once again, will be mostly about the triumphant accomplishments of “great men”? For these and other reasons, women have bypassed the STEM disciplines and the study of genius.

The historian Dean Keith Simonton, who has researched genius for more than forty years, has numerically demonstrated the underrepresentation of women in fields traditionally associated with genius. According to Simonton’s statistics, women make up only about 3 percent of the most noteworthy political figures in history. In the annals of science, fewer than 1 percent of notables are women, a mere drop in an otherwise all-male sea. Even in the more “female-friendly” domain of creative writing, female luminaries constitute only 10 percent of great writers. In the realm of music, for every Clara Schumann or Fanny Mendelssohn, there are ten well-known male classical composers.8 By way of conclusion, Simonton observed that although women constitute half the population, throughout history they have been depicted as “unimportant, inconspicuous, even irrelevant to human affairs.”9 One can choose to believe Simonton’s statistics or not. But the question he ultimately poses is this: Does this so-called underachievement arise from genetic inadequacy or from cultural bias? Many would consider the very question itself insulting, including the genius Virginia Woolf.

WOOLF WAS BORN IN LONDON INTO A WELL-TO-DO, UPPER-MIDDLE-CLASS family in 1882. Although provided with books and private tutors, the low-cost homeschooling she received was a far cry from that afforded her brothers in expensive boarding schools and then at Cambridge University. Once when doing research on the poet John Milton, she was denied access to an unnamed “Oxbridge” college library because of her gender. Angered by the inequity and curious as to how such gender bias had come to be, she went in search of female geniuses throughout history. What she concluded was that genius is an all-male social construct, as she described in her famous essay of 1929, A Room of One’s Own. Woolf’s observations about exceptional female accomplishment—and the barriers to it—still resound today.

A quiet room (in which to write), money (to pay the bills), and time to think (about things other than child-rearing)—for Woolf, those were metaphors for opportunity, the opportunity historically denied women. “Making a fortune and bearing thirteen children—no human being could stand it,” she wrote. “. . . In the first place, to earn money was impossible for them, and in the second, had it been possible, the law denied them the right to possess what money they earned.”10 Thus as engines of intellectual capital, “women did not exist. . . . It was impossible for any woman, past, present, or to come to have the genius of Shakespeare,”11 she wrote. Throughout history, she said, there had always been this assertion: “You cannot do this, you are incapable of doing that.”12 Among those who set the “thou cannot” barrier was the famous educator Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who wrote in 1758, “In general, women don’t like art, don’t understand it, and have no genius for it.”13

With defeat preordained for females, many female geniuses throughout history responded by disguising themselves and their gender. Jane Austen published Pride and Prejudice as an anonymous woman, and Mary Shelley did the same when she initially set loose Frankenstein. Other female geniuses assumed male noms de plume, including George Sand (Aurore Dudevant), Daniel Stern (Marie d’Agoult), George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans), Currer Bell (Charlotte Brontë), and Ellis Bell (Emily Brontë). Perhaps they would never enjoy the glory of recognition, but at least now their work had a chance of being published and read. How can a genius change the world if her work remains unknown?

The recognition Woolf gained and the issues she called out in her famous essay undoubtedly inspired and galvanized many female writers who came after her. The literary greats Toni Morrison (who wrote a master’s thesis on Woolf), Pearl S. Buck, Margaret Atwood, and Joyce Carol Oates all wrote or write under their own names, and today women authors seem to enjoy the same status and power of voice as men. But if this is true, why did Joanne Rowling, Phyllis Dorothy James, and Erika Mitchell think it necessary to become J. K. Rowling, P. D. James, and E. L. James? Why did Nelle Harper Lee leave off the Nelle? Rowling was told by her agent, Christopher Little, that she would sell more of her Harry Potter books if she disguised herself as a man.14

“To write a work of genius is almost always a feat of prodigious difficulty,” continued Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own. What made it difficult was that the world seemed indifferent to the extra weight placed upon a creative woman and that even men of genius were hostile to the notion that it should be lifted. “Accentuating all these difficulties and making them harder to bear is the world’s notorious indifference. . . . [But what] men of genius have found so hard to bear was in her case not indifference, but hostility [emphasis added].”15 Hostility is the child of fear—of losing authority, status, and wealth. The tendency to fear female accomplishment is part of what Woolf called “an obscure masculine complex.” It consists, she said, of a deep-seated desire, “not so much that she be inferior, but that he be superior.”16

To ensure their superiority, according to Woolf, males devised a simple strategy: make women look half size, and thereupon men appear twice as large. This she calls the “looking-glass,” or magnifying, effect: “Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size. . . . That is why Napoleon and Mussolini both insist so emphatically upon the inferiority of women, for if they were not inferior, they [the males] would cease to enlarge. That serves to explain in part the necessity that women are to men.”17

Napoleon had indeed said, “Women are nothing but machines for producing children.” Among those we consider great men, he was not alone in his misogyny. The poet George Gordon, Lord Byron, said of women, “They ought to mind home, and be well fed and clothed, but not mixed in society. Well educated, too, in religion, but to read neither poetry nor politics—nothing but books of piety and cookery. Music, drawing, dancing, also a little gardening and ploughing now and then.”18 Music? Why not, then, a female composer? The man of letters Dr. Samuel Johnson discounted that notion: “Sir, a woman’s composing is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well, but you are surprised to find it done at all.”19 A dog also came to mind when Charles Darwin contemplated marriage, carefully weighing the pros and cons of a dog versus a wife as a potential lifetime companion.20 Said Picasso about dogs, “There is nothing so similar to one poodle dog as another poodle dog, and that goes for women, too.”21

We might expect, or at least hope, that learned philosophers of the past might have risen above misogyny. But disappointingly, this was often not the case. Although we have Arthur Schopenhauer to thank for his remarkable metaphor “A person of genius hits a target that no one else can see,”22 he seems far from the mark when he wrote in On Women (1851), “It is only the man whose intellect is clouded by his sexual instinct that could give that stunted, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped, and short-legged race the name of the fair sex; for the entire beauty of the sex is based on this instinct. One would be more justified in calling them the unaesthetic sex than the beautiful. Neither for music, nor for poetry, nor for fine art have they any real or true sense and susceptibility, and it is mere mockery on their part, in their desire to please, if they affect any such thing.”23

Surely, objective scientists might judge the world impartially. Yet an early neuroscientist, Paul de Broca, after whom “Broca’s area” of the brain is named, declared in 1862 that brains are larger “in men than in women, in eminent men than in men of mediocre talent, in superior races than in inferior [read “African”] races.”24 Broca was incorrect, for brain size, it turns out, is mostly a factor of body size, not of gender or race. Perhaps the renowned theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking should also have kept quiet in 2005 when he stated, “It is generally recognised that women are better than men at languages, personal relations and multitasking, but less good at map-reading and spatial awareness. It is therefore not unreasonable to suppose that women might be less good at mathematics and physics.”25 That same year, economist and former Harvard president Lawrence Summers created a furor when he argued that men outperform women in maths and sciences because of biological difference, and discrimination is no longer a career barrier for female academics.26 Shortly thereafter, he was encouraged to resign—and did.

Even the scientist Albert Einstein did not think beyond the paradigms of his day when he said in 1920, evidently with a tinge of misgiving, “As in all other fields, in science the way should be made easy for women. Yet it must not be taken amiss if I regard the possible results with a certain amount of skepticism. I am referring to certain restrictive parts of a woman’s constitution that were given her by Nature and which forbid us from applying the same standard of expectation to women as to men.”27 Perhaps we should instead look to a different quote attributed to Einstein to explain the sexist and misguided comments of his contemporaries: “The difference between stupidity and genius is that genius has its limits.” Stupidity, however, appears timeless.

TO BE SURE, THE TIMELESS STUPIDITY OF IGNORING THE INTELLECTUAL potential of half of humanity is deeply embedded in our culture. In Genesis, as later interpreted by Jewish and Christian writers, Eve is said to be “formed out of man,” the mother of all things yet sinner and seductress. In Hinduism, according to the second-century B.C. Laws of Manu, no woman is independent, but each lives under the control of her father or her husband. Ancient Confucianism similarly advocated a hierarchical societal order based on gender differences. The three major Western religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—traditionally segregated women during worship, giving them a place removed from the high altar or the central point of prayer.

Who dictated the laws of the world’s great religions? Of course, they were the same male authority figures who set the rules for educational institutions in the West, including universities, professional schools, art academies, and music conservatories. Historically, only men were given the opportunity of a literate education, and only they went to university. The first woman to receive an academic degree was Elena Piscopia at the University of Padua in 1678. Bach moved to Leipzig in 1723 to take advantage of a free university education for his numerous sons, an opportunity not offered to his equally numerous daughters. A century and a half later, women were admitted to hear university lectures in Germany, but only if they remained behind a curtain. In 1793, they gained entry to the Paris Conservatory of Music but had to enter through a separate door; they were allowed to study musical instruments but not musical composition, creativity being deemed beyond their limited capacity. The Royal Academy [of Art] was founded in London in 1768 with two female members, Mary Moser and Angelica Kauffman, but not until 1936 was another woman elected. Women painters were not admitted to the state-sponsored School of Fine Arts in Paris until 1897; and even then, as in London, they were barred from nude anatomy classes, instruction crucial to drawing and the very foundation of painting.28 Nor could they gain normal access to other places necessary to their art. Among painters of animals in the nineteenth century, Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899) is perhaps the most famous for her realistic and detailed depictions.29 But she had a problem: to get close to her subjects at horse fairs and slaughterhouses, she needed to wear pants rather than the long skirts usual for women at the time. “I had no alternative,” she wrote, “but to realize that the garments of my own sex were a total nuisance. That is why I decided to ask the Prefect of Police for the authorization to wear masculine clothing.”30

Women couldn’t wear the pants. They couldn’t vote in the United Kingdom until 1918 and in the United States until 1920. Marie Curie couldn’t study the sciences or anything else at a university in Poland during the 1880s. Women couldn’t attend the famed University of Edinburgh until 1889. In 1960, Harvard had one female full professor, Yale and Princeton none.31 Women did not gain entrance as undergraduates to Princeton and Yale until 1969, and although women could attend Harvard classes as enrolled students at Radcliffe College beginning in the 1960s, Harvard did not officially merge with its sister school until 1999. The same year that Yale and Princeton went coed, 1969, the (male) dean of freshmen at Harvard, Francis Skiddy von Stade, declared, “Quite simply, I do not see highly educated women making startling strides in contributing to our society in the foreseeable future. They are not, in my opinion, going to stop getting married and/or having children. They will fail in their present role as women if they do.”32 No one at the time seems to have taken issue with von Stade, at least not in print. Without an education, women were assumed to be incompetent in financial matters, unable to get loans, have a credit card, or start a business without a male guarantor. In 1972, Michael Saunders, who now runs a real estate company in southwest Florida with $2 billion in annual sales, had an application for a business loan approved, only to have it rescinded when the bank found out that Michael was a woman. That same year, the U.S. Congress passed the Equal Opportunity Credit Act to end such gender discrimination. But as José Ángel Gurría, the secretary-general of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ruefully concluded at the end of a 2018 anti-bias report, “We are fighting centuries and centuries of tradition and culture.”33

Deeply embedded cultural bias has killed the creative careers of many gifted women. The father of the fledgling composer Fanny Mendelssohn issued this mandate to her in 1820 when she was fifteen: “What you wrote to me about your musical occupations, and in comparison to those of [your famous composer brother] Felix, was rightly thought and expressed. But though music will perhaps become his profession, for you it can and must only be an ornament, never the core of your existence. . . . You must become more steady and collected, and prepare yourself for your real calling, the only calling for a young woman—the state of a housewife.” Pressed by habitual self-doubts, twenty-year-old Clara Schumann said the following in 1839: “I once believed that I possessed creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not desire to compose. There has never yet been one able to do it. Should I expect to be that one?”34 The promising composer Alma Mahler was told by her husband, Gustav, in 1902, “The Role of composer falls to me. Yours is to be loving companion.” Eventually the marriage ruptured, and the frustrated Alma exclaimed, “Who helps me to find MYSELF! I’ve sunk to the level of a housekeeper!”35 Sofia Tolstaya, who bore her husband, Leo Tolstoy, thirteen children, saw her desire to create “crushed and smothered.” Although she edited and copied Leo’s lengthy War and Peace seven times, she left nothing creative of her own.

I have served a genius for almost forty years. Hundreds of times I have felt my intellectual energy stir within me and all sorts of desires—a longing for education, a love of music and the arts. . . . And time and again I have crushed and smothered these longings. . . . Everyone asks: “But why should a worthless woman like you need an intellectual or artistic life?” To this question I can only reply: “I don’t know, but eternally suppressing it to serve a genius is a great misfortune.”36

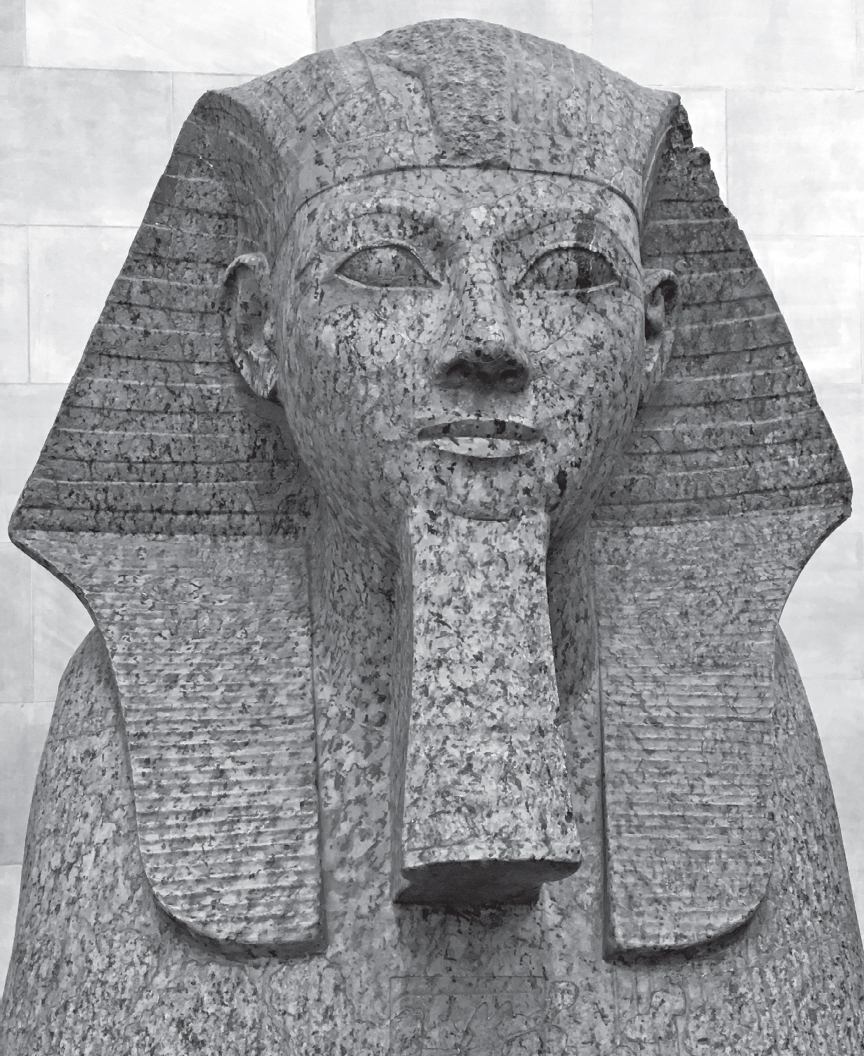

Many female geniuses were hidden from view for centuries because men wrote them out of history. Egyptian pharaoh Hatshepsut ruled from 1479 to 1458 B.C. and was called by the Egyptologist James Henry Breasted “the first great woman in history of whom we are informed.”37 So much statuary was produced during her twenty-year reign that nearly every major museum in the world has Hatshepsut monuments in its collection. Yet immediately after her death, the memory of Hatshepsut was systematically removed from Egyptian history. Statues of her were destroyed and inscriptions about her defaced. Her crime: Hatshepsut had made herself pharaoh (king), rather than playing the more traditional role of queen regent, and that, historians suggest, caused the destructive reaction. Not until the 1920s did archaeologists find and restore the once discarded evidence.38 Today Hatshepsut can be seen in all her masculine splendor in the Temple of Hatshepsut in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (Figure 2.1). But back in the day, even wearing a fake beard was not enough to save a woman’s fame from destruction.

FIGURE 2.1: The head of Hatshepsut as sphinx, with beard, excavated from debris in the Deir el-Bahri, at Thebes, Upper Egypt, during 1926–1928. The monument dates from 1479 to 1458 B.C. and weighs more than seven tons (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Craig Wright

The medieval nun Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) was no saint, at least not immediately. Instead, she was a “Renaissance man,” a medieval polymath long before Leonardo da Vinci. Preacher, poet, painter, politician, theologian, musician, student of biology, zoology, botany, and astronomy—Hildegard of Bingen was all of those.39 She corresponded with four popes (calling one an ass) and fought with Church authorities, who tried to silence her by placing her under interdict. For centuries after her death, Hildegard languished in obscurity. But beginning in the 1980s, with the advent of women’s studies programs and feminist criticism, Hildegard’s reputation as a medieval visionary was restored. In 2012, Pope Benedict XIII canonized her as Doctor of the Church, the fourth woman of thirty-five saints to be so designated.

Another female genius no longer hidden is the painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1656). For centuries some of Gentileschi’s works were attributed to male artists, including her father, Orazio, and the Neapolitan painter Bernardo Cavallino (1616–1656).40 Did patrons not believe that paintings of such drama and passionate intensity as hers could be the work of a woman? But there is a story behind this art: As a teenager, Gentileschi had been raped by her teacher and mentor, Agostino Tassi (1578–1644). The case had gone to trial, and Gentileschi had undergone a humiliating physical examination and torture by thumbscrew—a vise for crushing fingers—to prove her innocence.41 The assailant was convicted but served no sentence; the victim was branded a woman of lost virtue. For decades thereafter, Gentileschi’s paintings centered on acts of sexual aggression or female retribution for sexual assault (Figure 2.2). Many now consider Artemisia Gentileschi an artistic genius of the highest order, but in her day she was viewed mostly as a curiosity—a rare female painter in a man’s world and a cautionary tale about the dangers lurking therein. Even today a vestige of this legacy persists. Remembered as much for her backstory as for the quality of her painting, Gentileschi is now known as “the #MeToo painter.”

FIGURE 2.2: Genius changes the boundaries of convention, as can be seen in Artemisia Gentileschi’s uniquely intense and dramatically expressive Judith Beheading Holofernes (1611–1612). Here Judith wreaks vengeance on the Assyrian general Holofernes (as told in the apocryphal Book of Judith). This is the first of five works painted over three decades in which Gentileschi depicted the bloody decapitation of Holofernes (Museo Capodimonte, Naples).

Alamy Stock Photo

We could go on through the histories of uncredited, discredited, ignored, and unlucky female geniuses. The mathematician Ada Lovelace (1815–1852) was the first person, male or female, to realize that a nineteenth-century calculator need not be used only for math and numbers but could also store and manipulate anything that could be expressed in symbols: words, logical thoughts, even music—a “thinking machine,” she prophesized. The daughter of the genius Lord Byron, Ada called herself a “natural genius” in mathematics. Today she is recognized as one of the first computer programmers, but she died at age thirty-six of uterine cancer, promise unfulfilled.42 Rosalind Franklin (1920–1958) was an English chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose X-ray photographs provided the critical piece of information in the identification of the double-helix structure of DNA; the images were taken from her by male colleagues, and they, not she, received the Nobel Prize (for more on Franklin, see chapter 11). Lise Meitner (1878–1968) was an Austrian-Swedish physicist after whom chemical element 109, meitnerium, is named. She and Otto Hahn jointly discovered the process of nuclear fission in 1938–1939, the science behind the atomic bomb. But when the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded in 1944 it went to him alone.43 The signature style of art of the artist Margaret Keane (b. 1927), the subject of the Tim Burton film Big Eyes (2014), was appropriated by her agent/husband, Walter. Decades later, she sued, and a California judge demanded a “paint-off,” which demonstrated that Mrs. Keane, not Mr. Keane, was the real creator of her unique “big-eyed waifs.” The court awarded her $4 million, but by then Walter had squandered the money.44

Money is the great facilitator of human accomplishment regardless of gender. It is, as Virginia Woolf said, a proxy for opportunity. We know that women have enjoyed less monetary opportunity than men, being paid less for the same quantity and quality of work. In 1955, women in the United States earned 65 cents for each dollar earned by men. By 2006, the gap had narrowed to 80 percent, but it has not closed further since then.45 The U.S. Women’s National Team may have sued the U.S. Soccer Federation for equal pay in 2019,46 and the #timesup movement for equal pay in Hollywood may have gotten attention at the Golden Globes that year, but the fact remains that within each racial and ethnic group in the world, a woman earns less than a man. Perhaps more important for genius, only 17 percent of U.S. startups are founded by women and to them go only 2.2 percent of venture capital funds from which to grow an idea.47

Aretha Franklin sang about something else on which women have historically been shortchanged: R-E-S-P-E-C-T. In 2018, the New York Times began to atone for the fact that since 1851 the vast majority of its obituaries had been men (about 80 percent are still that way).48 To ensure recognition commensurate with accomplishment—and consequently more female role models—the paper launched the project “Overlooked,” publishing memorial pieces on geniuses it had skipped, such as the novelist Charlotte Brontë, Brooklyn Bridge builder Emily Roebling, and the poet Sylvia Plath. Similarly, trade book writers and filmmakers have produced projects such as Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race (2016), a bestselling book that became a hit film. Such initiatives alert us to cultural bias. Overtly or covertly, they urge us to remove it.

SOMETHING ELSE IS HIDDEN FROM OUR EYES: WOMEN EXHIBIT MANY of the same biases against women as do men. The authors of the book Sex and Gender in the 2016 Presidential Election have shown that whereas a majority of men look unfavorably on power-seeking women, 30 percent of women are biased against them as well.49 A 2019 study, “Prejudice Against Women Leaders: Insights from an Indirect Questioning Approach,” done at the Heinrich-Heine-University in Germany, tested 1,529 participants. When queried overtly, 10 percent of women and 36 percent of men were deemed to hold prejudicial views toward women leaders. When assured complete confidentiality, however, those numbers jumped to 28 percent of women and 45 percent of men.50 Researchers have also discovered that not only were the women in these studies prejudiced against other women, they were often unaware of that fact. Psychologists call this discrepancy between self-perception and reality “implicit bias,” “unconscious bias,” or “blind-spot bias.”51 As the 2010 AAUW report Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics stated, such blind-spot biases, held by both women and men, are more difficult to eradicate because we are not aware of them.52

Remember Catherine Nichols’s experiment? Female literary agents overwhelmingly preferred to review a manuscript of a novel sent out under a male pseudonym. In 2012, a group of Yale psychologists tested for bias among 127 science professors, men and women, asking them to review an application for a position as manager of a science lab.53 An identical CV was distributed, sometimes under the name of a male applicant and sometimes under the name of a female. The male applicant was deemed preferable for the position, being judged not only more hirable but also worthy of a higher salary and of mentoring. Surprisingly, the bias against the woman was held in equal measure by women and men. Sometimes women are even more biased against women than men are. In 2013, Harvard researchers Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald published the results of a “Gender-Career Implicit Association Test” that explored attitudes about women in the workplace and at home. They found that 75 percent of men held the predictable stereotype regarding the place of a woman, but so did 80 percent of women.54

The point of this is not to try to exonerate men by shifting the blame to women. On the contrary, the above studies show how effective men have been at subliminally ingraining gender bias. Historically, men have controlled most things, including social discourse about gender and about genius. If women today are just as likely as men to believe that a game-changing leader must be a tall, strong white man carrying a briefcase, who’s really to blame?

Which brings us to the question of the allocation of genius by gender. Is there really a difference? Did Charles Dickens really have more literary genius than Louisa May Alcott? Did Thomas Edison, who is famous for his “genius is 99 percent perspiration” quote, really possess more tenacity than Marie Curie, who labored for years stirring vats of pitchblende under dangerous conditions? Why is Edison, not Curie, the poster child for perseverance? Indeed, the impressive, bestselling book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance (2016) has no mention of Curie, nor does it have a discussion of, or index entry for, “women and persistence” or “women and grit.” Why has this habit of female excellence been hidden from us? History demonstrates that to become and be recognized as a genius, a woman has needed an extra dose of grit.

The Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison knew this. Consider her working arrangements when she was at her peak compared with those of fellow Nobel Prize winner Ernest Hemingway when he was at his. In 1965, Morrison was a single mother living in a small, rented house in Queens, New York. She would rise at 4:00 A.M. to write, then drive her two sons to school in Manhattan, where she worked as an editor at Random House, and pick them up when her workday ended to drive them home. After she put the boys to bed, she would go back to work. In 1931, the wealthy in-laws of Ernest Hemingway gave him the title to the largest and highest house on the island of Key West. There he spent his mornings writing in the separate studio attached to the house and his afternoons fishing. In 2019, the Guardian published an article by Brigid Schulte and the title says it all: “A Woman’s Greatest Enemy? A Lack of Time to Herself.” To carve out time to create requires extra grit.55

What might all this mean for the employers and spouses of women today? They should provide equal space, pay, and, perhaps most important, time. What might this mean for parents concerned with the happiness and future success of their offspring? Well, they should no longer dress daughters in the once popular T-shirt proclaiming “I’m too pretty to do homework, so my brother does it for me,” for one. They should also be careful not to perpetuate gender stereotypes in more subtle ways. A recent article in the New York Times, “Google, Tell Me. Is My Son a Genius?,” pointed out that parents today are 2.5 times as likely to ask online “Is my son gifted?” than “Is my daughter gifted?” and similarly 2.0 times as likely to inquire “Is my daughter overweight?” as they are for a son.56 Thus, the current prejudice ratio for genius is apparently 2.5 to 1 against women. The game has been rigged for a long time and remains rigged because hidden cultural biases are difficult to discard, even for progressive, modern-day parents.

A final statistic, coming, again, from Professor Dean Keith Simonton and his book Greatness: Who Makes History and Why: Simonton posited that for every identifiable female genius, it is possible to name ten males.57 If this is true, it would suggest, in the roughest of terms, that for every twenty potential geniuses, the empowerment of nine has been suppressed owing to gender bias. If you were running a business—let’s call it the Human Potential Company—and nine out of every twenty geniuses working for you were kept underemployed, how smart would that be? Must stupidity, as Einstein suggested, really last forever?

Breaking a stupid habit requires action and begins with cultivating awareness. Understand that “the missing nine” are lost because of gender bias. Understand that the cause is culture, not lack of genetic gifts. Understand that women have the same hidden habits of genius as men and perhaps an extra dose of resilience. Think about the implications of the way you talk to your daughters about things such as homework and achievement versus the way you talk to your sons. Finally, if you recommend only one chapter of this book to your friends, colleagues, and family members, make it this one.