Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603) of England had the finest traditional education that a king’s money could buy. While her father, Henry VIII, was sending Anne Boleyn and his subsequent wives to the chopping block, he provided his children with the best private tutors, knowing that someday one of them, even a girl, might rule. Elizabeth, his youngest child, received a classical education that was typical for a Renaissance humanist prince but exceedingly rare for a woman at the time. Elizabeth not only studied history, philosophy, and ancient literature but also read the early Church fathers, the Greek New Testament, and the Latin writings of Reformation theologians. Her tutor, the Oxford don Roger Ascham, said of his star pupil when Elizabeth was only seventeen, “The constitution of her mind is exempt from female weakness [!], and she is endued with a masculine power of application. No apprehension can be quicker than hers, no memory more retentive. French and Italian she speaks like English; Latin, with fluency, propriety and judgement; she also spoke Greek with me, frequently, willingly, and moderately well.”1

But Elizabeth’s education did not stop when her tuition with Ascham ended; even after she became queen in 1558, Elizabeth remained an autodidact for life. As she once wrote to her stepmother Queen Katherine Parr, “The wit of a man, or woman, wax[es] dull and unapt to do or understand anything perfectly, unless it be always occupied upon some manner of study.”2 Having set three hours of reading daily as her standard, Elizabeth was able to remind Parliament on March 29, 1585, “I must yield this to be true: that I suppose few (that be no professors) have read more.”3 Said her contemporary William Camden, “She informed her minde with most apt documents and instructions, and daily studied and applied good letters, not for pomp but for practice of love and virtue insomuch as she was a miracle for learning among the Princes of her Time.”4

Indeed, Elizabeth was a miracle of learning. But what practical good did all her learning avail her? It gave her power. As one of Elizabeth’s courtiers, Francis Bacon, famously declared, perhaps with Elizabeth in mind, “Knowledge is power.” Learned Elizabeth had earned a standing equal or superior to that of the all-male diplomatic corps of the day. Her fluency in Latin, French, and Italian enabled her to speak with foreign envoys (and understand them while they spoke with one another) as well as read letters from abroad without the need for interpreters. When, in 1597, a Polish ambassador attempted to upstage the queen by speaking in Latin, she cut him off, issuing a wholly extemporized harangue in that language. Then she turned her back on the unfortunate emissary and said to her courtiers with false humility, “My lords, I have been forced this day to scour up my rusty old Latin.”5

Having acquired power and authority through learning, Elizabeth had no intention of relinquishing it. As her personal motto, she chose the Latin Video et taceo (“I see all and say nothing”). The huge imbalance between what Elizabeth had in her head and what she publicly said worked to her advantage in all things politic. Compare Elizabeth’s approach to the current British and American heads of state Boris Johnson and Donald Trump, who blast out impetuous tweets daily. By knowing all and saying nothing, Elizabeth ruled for forty-four years, at the time the longest reign of any English monarch, laid the foundations of the British Empire, and gave her name to an entire epoch, the Elizabethan era. Having judicious control of everything she had put into her head allowed genius Elizabeth to keep it attached and to keep her nation on course.

CALL IT A LUST FOR LEARNING, A PASSION TO KNOW, OR A POWERFUL curiosity—it’s all the same impulse, and we all have it, albeit to varying degrees. Although invisible and immeasurable, curiosity is an essential part of each person’s personality, and it is inextricably intertwined with other personal traits, particularly with passion. For geniuses, more than the rest of us, the desire to understand is tantamount to an itch. Great minds are annoyed by a mysterious problem and want a solution. “They experience a ‘divine discontent,’ as Jeff Bezos called it,” between what is and what might be—and they act. Marie Curie, as we will see, was driven to solve the mystery of radiation in pitchblende. Albert Einstein felt impelled by the mystery of the compass needle that would not move. Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865) was curious about a discrepancy in mortality rates in a Viennese maternity hospital and discovered the virtues of handwashing. Curious people want to bring comfort to a discomfort; there is a disjunction between what they see and what they know—and they feel compelled to reconcile the two.

With varying degrees of frequency and intensity, we all want to know what we don’t. Experts in the psychology of education and marketing try to capitalize on this deep-seated human desire. Sigmund Freud, when hunting for mushrooms with his children and finding a prize specimen, did not exclaim, “Look, there it is!” Rather, he put his hat over it and let the children uncover the secret themselves. Freud intuited what more recent psychologists demonstrated in a 2006 study: “When asked to recall the information they had learned, subjects were far better at remembering those items about which they had expressed surprise.” Children remember more when they discover things themselves.6 Perhaps the way to learn is not to be taught, but to be curious.

Leonardo da Vinci has been called “the most relentlessly curious man in history.”7 That’s hyperbole, perhaps, but Leonardo asked a lot of questions, both of others and of himself. Consider, for example, a single day’s “to-do” list that he wrote while in Milan around 1495.8

- Calculate the measurement of Milan and its suburbs.

- Find a book describing Milan and its churches, which is to be had at the stationer’s on the way to Cordusio.

- Discover the measurement of the Corte Vecchia [old courtyard of the duke’s palace].

- Ask the Master of Arithmetic [Luca Pacioli] to show you how to square a triangle.

- Ask Benedetto Portinari [a Florentine merchant passing through Milan] by what means they go on ice at Flanders?

- Draw Milan.

- Ask Maestro Antonio how mortars are positioned on bastions by day or night.

- Examine the crossbow of Maestro Gianetto.

- Find a Master of Hydraulics and get him to tell you how to repair a lock, canal and mill, in the Lombard manner.

- Ask about the measurement of the sun, promised me by Maestro Giovanni Francese.

Leonardo’s questions extend to many fields: urban planning, hydraulics, drawing, archery and warfare, astronomy, mathematics, and even ice skating. How many of those subjects had he studied in school? None, for Leonardo was of illegitimate birth and thus barred from the only system of formal education then available, that of the Roman Catholic Church. He had received no instruction in Latin or Greek, the learned languages of the day, and accordingly later said of himself, “I am a uomo senza lettere”9—an unlettered man. Thus Leonardo belongs to the first of two types of curious individuals: those who learn experientially and those who learn vicariously by reading—in other words, those who do or discover and those who read about what others have done or discovered.

Leonardo was a doer. He painted, of course, but he also went into the mountains to examine rocks and fossils and to the tidal marshes to look at the wings and flying habits of dragonflies. He took apart machines to see how they worked and took apart humans to the same end. He recorded all of his discoveries in what amounted to about thirteen thousand pages of notes and drawings.

What made Leonardo so curious? Among the earliest attempts to explain his inquisitiveness was a theory advanced in 1910 by the genius Sigmund Freud. Strange as it may seem today, Freud attributed Leonardo’s curiosity to the fact that he was apparently gay, which had “caused him to sublimate his libido into the urge to know.”10 Freud believed he saw physical evidence of Leonardo’s gayness in the androgynous faces Leonardo depicted in some of his paintings, most notably his St. John the Baptist (Figure 5.1), as well as in the artist’s handwriting.

Many geniuses throughout history have been left-handed,11 and Leonardo may have been the most famous “lefty” of them all. But Leonardo had another oddity in his script: he wrote almost everything backward. Of course, there is a simple explanation for this: For a left-handed person, writing backward (right to left) removes the possibility that the writer’s hand will pass through and smudge the ink.

But Freud saw more than a practical explanation: Leonardo’s backward drawing was a mark of “secretive behavior,” a sign of his repressed sexuality in a less-than-open society. By means of such coded writing Leonardo might remain private, an enigma as to his thoughts and desires. Freud’s conclusion: “The sublimated libido reinforces curiosity and the powerful investigation impulse. . . . Investigation becomes to some extent compulsive and substitutive of sexual activity.”12 In brief: curiosity can manifest as a substitute for sex.

FIGURE 5.1: The face in Leonardo’s St. John the Baptist (1513–1516): male or female? (Musée du Louvre, Paris).

Dennis Hallinan: Alamy Stock Photo

Though all of this may seem far-fetched, Leonardo himself remarked in his Codex Atlanticus, “Intellectual passion drives out sensuality.”13 Is homosexual passion really a spur of curiosity and ultimately creativity, as Freud suggests? Not according to a 2013 report in The International Journal of Psychological Studies that summed up current research on the matter in these terms: “The present findings were compatible with previous studies that homosexuals are no more or less creative.”14 Although the life experiences of gay individuals may open up new vantage points of otherness, homosexuals are apparently no more or less likely to be curious—and become creative geniuses—than are heterosexuals.

TO CREATE HIS FAMOUS PAINTINGS, INCLUDING THE MONA LISA, the inquisitive Leonardo seems to have taken a step backward and asked, “What is it that I am painting, and how does this living organism work?” These questions he pursued by picking up not a brush to paint but a knife to cut. To satisfy his curiosity about anatomy, Leonardo dissected dead pigs, dogs, horses, and oxen, and also humans, including a two-year-old child.

Dissection of humans in this or any day requires courage—a combination of passion and a tolerance for risk. And Leonardo had courage in abundance, as his early biographer Vasari noted in several places in his The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550).15 To begin with, where to obtain human cadavers? In an era in which Church authorities still considered dissection heresy, Leonardo did not explicitly identify his sources, though we know that at least one came from the hospital of Santa Maria Novella in Florence.16

Once Leonardo had obtained the bodies, things only got worse. The weather in Milan and Florence can be hot. To peel back layers of skin and lift up tendons, some degree of firmness and integrity of the tissue must be present. Without refrigeration and air-conditioning, once living tissue degenerates and approaches liquid form. Leonardo’s dissections seem to have been done under the secrecy of night, as he reported to his readers in these words:

But though possessed of an interest in the subject, you may be deterred by natural repugnance, or, if this does not restrain you, then perhaps by the fear of passing the night hours in the company of these corpses, quartered and flayed and horrible to behold; and if this does not deter you then perhaps you may lack the skill in drawing essential for such representation; and even if you possess this skill it may not be combined with a knowledge of perspective, while if it is so combined, you may not be versed in the methods of geometrical demonstration or the method of estimating the forces and strength of muscles, or perhaps you may be found wanting in patience so that you will not be diligent.17

FIGURE 5.2: Leonardo’s drawing of the bones, muscles, and tendons of the hand, arm, and shoulder. The text is a beautifully clear Italian, written backward (Royal Collection Trust, Windsor Castle).

Janaka Dharmasena: Alamy Stock Photo

And then there would have been the stench. But Leonardo was not dissuaded from the task at hand. Did he even notice? Possibly not, for Vasari reports that as a prank Leonardo once affixed to a shield the dead bodies of several ferocious creatures that soon stunk to the high heavens. The stench went unnoticed by the creator.

This raises the question: When a genius is in the height of passionate investigation, does he or she notice discomfort? Michelangelo didn’t bewail his fate as he reached up for four years, sixteen hours a day, during his “agony” beneath the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. Isaac Newton seems not to have complained when he stuck a large needle into his eye and wiggled it around to measure the effect on his perception of color. Nikola Tesla soldiered on after more than once shocking himself with high-voltage electric current. Do the fires of creative curiosity drive away pain?

Having persevered, what did Leonardo learn as a result of his many dissections? Nothing less than the structure of human anatomy understood in modern terms. He was the first to identify the condition we now call arteriosclerosis. He was the first to recognize that seeing is the process of light being dispersed on the whole of the retina, not on a single point of the eye. He was the first to discover that the heart has four chambers, not two. And he was the first to demonstrate that blood swirling as vortices at the base of the aorta forces a closing of the aortic valve—something not verified in published medical journals until 1968.18 And so it goes. Eventually, 450 years after his death, medical science caught up with the genius of Leonardo, with the advent of machines for computerized axial tomography (CAT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that could see inside the body without cutting it open. But even today, some physicians prefer to use copies of Leonardo’s handwritten drawings (Figure 5.2), rather than the computer-generated images in medical textbooks, believing that the master’s crosshatched shadings more clearly reveal the functional processes within the body.19 Leonardo’s curiosity taught him how to paint the muscles in Mona Lisa’s smile,20 but it also led him to discoveries far beyond the world of art.

When Leonardo breathed his last at the age of sixty-seven, his legacy consisted of fewer than twenty-five finished paintings.21 What he left behind in abundance, by contrast, were his voluminous notes and 100,000 sketches and preliminary drawings. Why so few paintings from arguably the greatest artist of all time? Because once he had figured out how to do something, his curiosity drove him on to the next project. He had a greater desire to learn than he did to finish.

MOST OF US DO NOT DISSECT ANIMALS OR DIVERT STREAMS, AS DID Leonardo, to satisfy our curiosity. Most of us learn vicariously by reading, and we do so for at least three reasons: (1) to acquire information that can lead to knowledge, wisdom, authority, and power; (2) to expand our life experiences, thereby gaining insight into human behavior without having emotional skin in the game; and (3) to find role models by which to set our own moral compass.

One genius who has changed the lives of millions is Oprah Winfrey. As a TV reporter and talk show host, Oprah’s curiosity and desire to learn were amply demonstrated in the course of the thirty-seven thousand interviews she conducted. No less impactful on her TV audience was Oprah’s Book Club, which caused people who had not picked up a book since high school to do so. As a child, Winfrey had to fight so as to learn. “You’re nothing but a something-something bookworm,” she has recalled her mother yelling as she grabbed the book from her daughter’s hand. “Get your butt outside! You think you’re better than the other kids. And I’m not taking you to no library!”22

The great-great-granddaughter of a slave, Winfrey was born to a young single mother, was moved from home to home, was sexually molested in her childhood and early teens, and had a child out of wedlock at age fourteen. “I went back to school after the baby died,” she recalled, “thinking that I had been given a second chance in life. I threw myself into books. I threw myself into books about troubled women, Helen Keller and Anne Frank. I read about Eleanor Roosevelt.”23

From poverty Winfrey rose to become a media mogul and the first African American billionaire. How did she do it? By continually working to improve herself, and others, through reading. Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison said about Winfrey, “I have very seldom seen a home with so many books—all kinds of books, handled and read books. She’s a genuine reader, not a decorative one. She’s a carnivorous reader.”24 In 2017, Winfrey spoke of the importance of reading and education but never once mentioned learning in the context of a school, a college, or a university. “[It] matters because it’s an open door to a real life, and you can’t get through this life without it and succeed. It’s an open door to discovery and wonder and fascination and figuring out who you are, why you’re here, and what you came to do. It’s an invitation to life, and it feeds you forever.”25

LIKE OPRAH WINFREY, BENJAMIN FRANKLIN WAS A LIFETIME learner, both a reader and a doer. In his autobiography (1771), Franklin confessed that he was born a bibliophile: “From my infancy I was passionately fond of reading, and all the little money that came into my hands was laid out in the purchasing of books. I was very fond of voyages. My first acquisition was Bunyan’s works in separate little volumes.”26 In 1727, Franklin formed the Junto Club, a group of twelve tradesmen who met each Friday to discuss issues of morality, philosophy, and science. Eventually, Franklin accumulated 4,276 books, one of the largest libraries, public or private, in the American colonies.27

John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Daniel Defoe’s An Essay upon Projects, and Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans were Franklin’s early companions. Later, “ashamed of my ignorance in figures which I had twice failed in learning when at school,” he worked through all of Cocker’s Arithmetick (first edition London, 1677) and taught himself a bit of geometry as an aid to celestial navigation. To make himself a man of the world, Franklin learned to speak French and Italian and obtained a reading knowledge of Spanish and Latin. He found time for such self-improvement mostly on Sundays, when he determined that the traditional Christian devotional hours would be better spent in solitary learning than “in the common attendance on public worship.”28 A latter-day genius, Bill Gates, said much the same in 1997: “Just in terms of allocation of time resources, religion is not very efficient. There’s a lot more I could be doing on a Sunday morning.”29

At age forty-two, Ben Franklin retired from his profession as newspaper and magazine publisher to the American colonies to pursue other interests. His aim now was to satisfy his insatiable scientific curiosity. What caused a high-pitched violin to break a glass? Why does electricity go through water but not wood? Such questions then fell under the heading of natural philosophy, what we today call physics. (The term “scientist” was not coined until 1833.) “When I disengaged myself from private business, I flattered myself that, by the sufficient tho’ moderate fortune I had acquired, I had secured leisure during the rest of my life for philosophical studies and amusements.”30 Never mind that he knew only shopkeeper’s math and no physics. Again, curious Ben would teach himself what he needed.

Franklin’s curiosity about electrical science was pricked by a serendipitous event. In 1746, a traveling lecturer, Archibald Spencer of Edinburgh, arrived in Philadelphia and demonstrated the effects of static electricity.31 Intrigued, Franklin purchased Spencer’s electricity-generating devices on the spot, began to read about electricity, and started to experiment, mostly for fun. As he said of this exploration, “I never was before engaged in any study that so totally engrossed my attention and my time as this has lately done, what with making experiments when I can be alone, and repeating them to my friends and acquaintances, who . . . come continually in crowds to see them.”32 In one such experiment before a crowd, Franklin attempted to kill (and cook) a Christmas turkey by means of electrocution. In the excitement of the moment, he forgot to don his insulated shoes and nearly electrocuted himself.33

Between 1746 and 1750, Franklin shifted from performing parlor tricks to seriously investigating electricity. In 1752, he boldly flew a kite in an electrical storm. When lightning struck it, a line carried the charge down to a set of keys that jangled, just as they might if connected to an electrical charge emanating from a Leyden-jar battery on the ground. That was dangerous business: indeed, the next year the German physicist Georg Wilhelm Richmann electrocuted himself when trying to duplicate Franklin’s experiment.34 But Franklin had proved that lightning in the sky and electricity on earth are one and the same, that lightning moves from ground to cloud with as much intensity as from sky to earth, and that electricity is neither an ether nor a fluid but rather a force that, like gravity, pervades all nature. In recognition, he was awarded not only honorary degrees by Yale and Harvard but also the eighteenth-century equivalent of the Nobel Prize in Physics, the Copley Medal of the Royal Society (of London). Inquisitive to the end and even beyond, Franklin wrote to a friend in 1786 that he had experienced much of his world but was now “feeling a growing curiosity to see the next.”35 Four years later, his wish was granted.

THE SCIENTIST-INVENTOR NIKOLA TESLA (1856–1943) ALSO HAD a lust to learn about electricity. The results of his pursuits led to the universal adoption of alternating current, the system still in use today, as well as the induction motor, a device still used to power much of the world. The honorific eponym of the carmaker Tesla, he was a visionary who foresaw solar heating, X-rays, the radio and MRI machine, robots and drones, cell phones, and the internet. Like Franklin before him, Tesla was a passionate bibliophile from his earliest days, as he wrote in his autobiography. My father had a large library and whenever I could manage to, I tried to satisfy my passion for reading. He did not permit it and would fly into a rage when he caught me in the act. He hid the candles when he found that I was reading in secret—he did not want me to spoil my eyes. But I obtained tallow, made the wicking and cast the sticks into tin forms, and every night I could cover the keyhole and the cracks in the door and read, often til dawn.36

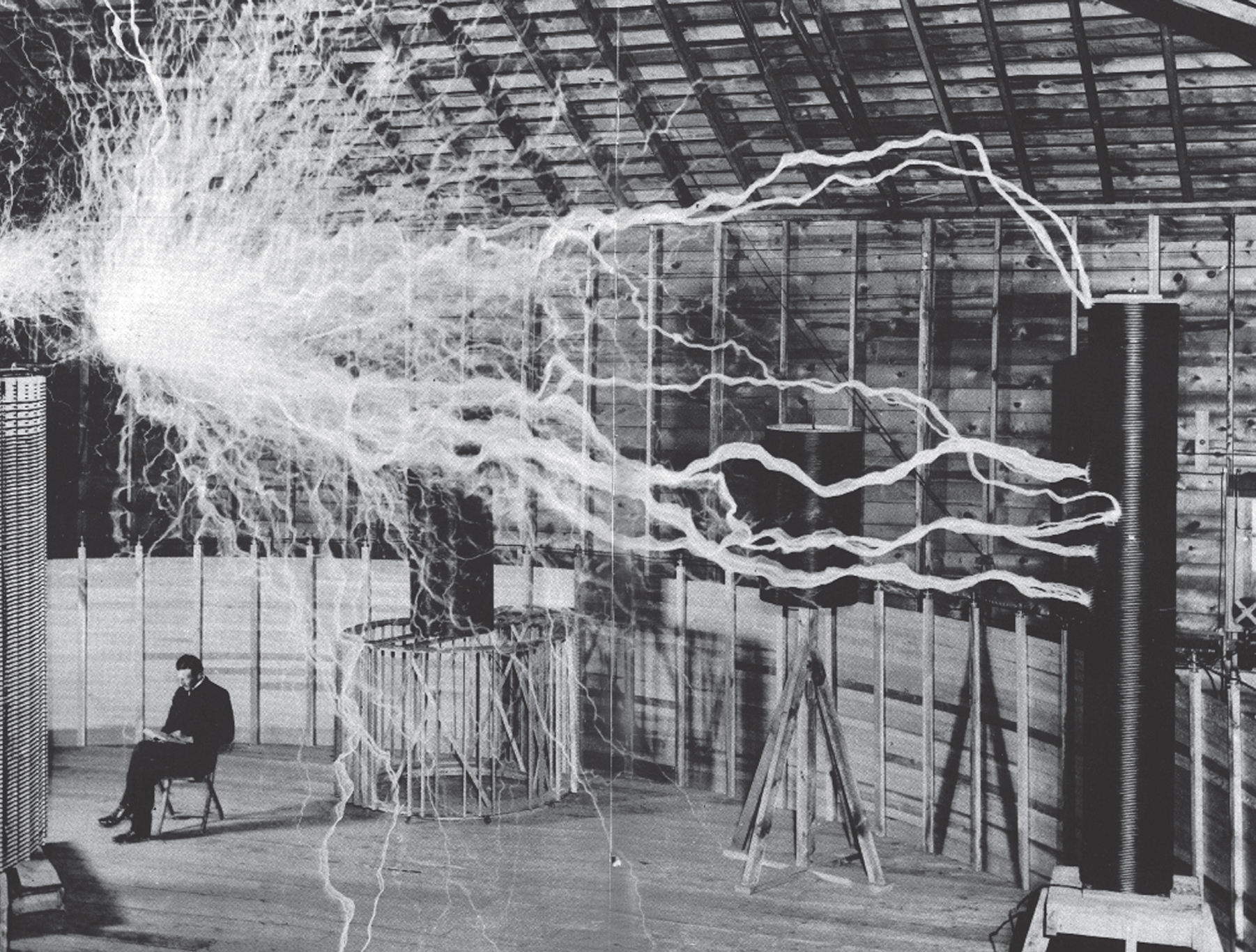

FIGURE 5.3: Nikola Tesla in his Colorado Springs lab, 1899 (Francesco Bianchetti, Corbis).

Science History Images: Alamy Stock Photo

In addition to studying physics, math, and electrical engineering, mostly on his own, Tesla drank in philosophy and literature. He claimed to have read all of the multiple volumes of Voltaire as well as committed to memory Goethe’s Faust and several Serbian epics—feats possible owing to his photographic memory.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, at least that many might be written about the accompanying photograph (Figure 5.3). It shows Nikola Tesla in his laboratory in 1899, impeccably dressed, with starched collar and polished shoes. In his hands he holds a book, a copy of Rogerio Boscovich’s Theoria philosophiae naturalis (1758).37 Tesla reads, oblivious to the swirls of electricity bolting around him. He created these “electrostatic thrusts,” as he called them, by means of “Tesla coils” built in a specially constructed laboratory in Colorado Springs, Colorado.38

Tesla’s ultimate aim was to create a new electrical “world system” that could transport not only raw electricity but also information and pleasure of all sorts (news, stock quotes, music, and phone calls) instantly and without wires around the globe. Needless to say, the experiments he did with blasts of high-voltage electricity in his lab were dangerous.39 The photo that we see here has actually been “Photoshopped” by Tesla, who superimposed an image of waves of electricity on top of a simple one of himself sitting. The result was an act of self-promotion intended to impress prospective investors and the general public alike. In the midst of the storm is the image that Tesla wished to create of himself: a genius quietly reading.

THE MODERN GENIUS ELON MUSK, THE CURRENT CEO OF TESLA— the name was chosen not by Musk but by the company’s founder—has also been a voracious reader since childhood. The driving force behind not only an electric car company but also SolarCity, Hyperloop, and SpaceX, young Musk always had a book in hand. Said his brother, Kimbal, “It was not unusual for him to read ten hours a day. If it was the weekend, he could go through two books in a day.” Musk himself recounts how around the age of ten, “I ran out of books at the school library [in Pretoria, South Africa] and the neighborhood library. This is maybe the third or fourth grade. I tried to convince the librarian to order books for me. So then, I started to read the Encyclopaedia Britannica. That was so helpful. You don’t know what you don’t know. You realize there are all these things out there.”40

So from childhood Musk read “from when I woke up until when I went to sleep.” Eventually, he read so much that he seemed to know everything. Musk’s mother recalled that whenever her daughter, Tosca, had a question, she’d say, “Well, go ask genius boy.”41 When asked how he had learned enough “rocket science” to help draft the booster designs for his aerospace company (SpaceX), he answered very quietly, “I read a lot of books.”42 Musk’s aim is to get to Mars.

WAS ELON MUSK BORN CURIOUS, OR IS HIS CURIOSITY AN ACQUIRED trait, or some of both? The psychologist Susan Engel, the author of The Hungry Mind: The Origins of Curiosity in Childhood (2015), stated that curiosity, like intelligence, is mostly innate and a stable part of one’s personality: “From birth some children may be more likely to explore novel spaces, objects, and even people.”43 Yet in a 2010 survey of all fifty U.S. states, researchers seeking to identify the catalyst of “giftedness” among children found that psychologists in forty-five of the states tested for a high IQ but only three for motivational curiosity.44 Which is more essential to greatness, intelligence or curiosity?

Eleanor Roosevelt would have said curiosity. As she declared in 1934, “I think, at a child’s birth, if a mother could ask a fairy godmother to endow it with the most useful gift, that gift would be curiosity.”45 Indeed, recent research has linked curiosity to happiness, satisfying relationships, increased personal growth, increased meaning in life, and increased creativity.46 Moreover, curiosity may play a role in the very survival of our species, as Jeff Bezos suggested in a 2014 interview on Business Insider: “I think it’s probably a survival skill that we’re curious and like to explore. Our ancestors, who were incurious and failed to explore, probably didn’t live as long as the ones who were looking over the next mountain range to see if there were more sources of food and better climates and so on and so on.”47 Like Musk with his SpaceX program, Bezos, via his Blue Origin private space company, is looking with curious eyes over to the next planet.

As to the incurious of this world: perhaps they did not begin life that way. Many evolutionary psychologists believe that humans are born curious but lose their innate inquisitiveness over time.48 But a childlike curiosity seems to always accompany a genius. As Albert Einstein said of himself in his later years, “I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious.”49

AS A CHILD, ALBERT EINSTEIN WAS INTRIGUED BY MECHANICAL gadgets, toy steam engines and puzzles in particular. He also played with a set of tiny stone building blocks (the predecessors of today’s Legos), and he would arrange the pieces to conform to a visual concept in his mind. (Einstein’s set survives and was for sale in 2017 at Seth Kaller, Inc., for $160,000.) Einstein later recalled how at age four or five a compass caught his attention, and he became transfixed by the way the needle would remain north pointing rather than move as he turned it. “I can still remember—or at least I believe I can remember—that this experience made a deep and lasting impression on me. Something deeply hidden had to be behind things.”50 We have all puzzled at the immobile compass needle, but only one of us followed his curiosity to arrive at a Theory of Special Relativity.

When he was ten, Einstein got his hands on a series of short “popular science” volumes entitled People’s Books on Natural Science (Naturwissenschaftliche Volksbücher, 1880) by Aaron Bernstein, which he read “with breathless attention.”51 Posed within were questions to which the curious Albert wanted answers: What is time? What is the speed of light? Is anything faster? Bernstein asked his reader to imagine a speeding train and a bullet shot through one side of a train car; the path of the bullet would appear curved inside the train as it raced forward. Einstein, when later working on his Theory of General Relativity and curvilinear space-time, asked his reader to imagine an elevator ascending rapidly but with a pinhole on one side allowing for the intrusion of a beam of light; by the time the light reached the other side of the lift, it would appear to be a descending arc. Said a family friend, Max Talmey, of Einstein’s youth, “In all those years, I never saw him reading any light literature. Nor did I ever see him in the company of schoolmates or other boys his age.”52

Alone, Einstein educated himself. At the age of twelve, he taught himself algebra and Euclidean geometry, and shortly thereafter integral and differential calculus. After he entered college, the self-schooling continued. The Polytechnic Institute in Zurich did not teach him what he was passionate to learn: cutting-edge physics. Thus Einstein, on his own, studied the electromagnetic equations of James Clerk Maxwell, the molecular structure of gases propounded by Ludwig Boltzmann, and the atomistic electric charges described by Hendrik Lorentz. After college, Einstein and two colleagues formed a club, the Olympia Academy, collectively to educate themselves, just as Franklin had done 170 years earlier with his Junto Club. Together Einstein’s group read and discussed, among other works, Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, David Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature, and Baruch Spinoza’s Ethics. Einstein’s disappointing experience in college later caused him to say, “It is, in fact, nothing short of a miracle that the modern methods of instruction have not yet entirely strangled the holy curiosity of inquiry.”53 Mark Twain is believed to have once said, “I have never let my schooling interfere with my education.” Einstein seems to have riffed on that idea when he observed with irony, “Education is that which remains, if one has forgotten everything he learned in school.”54

EINSTEIN SHOULD NOT HAVE EXPECTED OTHERWISE. MOST SCHOOLS—even top-flight colleges and universities—don’t explicitly teach the most important thing to learn in life: how to become a lifetime learner. Thus emblazoned over the entry arch to every academic institution should be these words: Discipule: disce te ipse docere (“Student: learn to teach thyself”).55 Students may receive information and learn methodologies in school, but the game changers of this world acquire the vast majority of what they know over time and on their own. Perhaps the science fiction writer Isaac Asimov got close to the truth when he said in 1974, “Self-education is, I firmly believe, the only kind of education there is.”56

SHAKESPEARE WAS ONCE CHASTISED BY HIS CONTEMPORARY BEN Jonson for having “little Latin and less Greek”—but at least the Bard had acquired some Latin and Greek. Mozart and Michael Faraday never had any formal schooling. Abraham Lincoln had a total of fewer than twelve months. Leonardo became the foremost medical scientist of his day without training in medical science. Michelangelo, Franklin, Beethoven, Edison, and Picasso never went beyond a bit of primary school. Elizabeth I and Virginia Woolf were homeschooled. Einstein left high school but after a year returned to prep for college. Tesla abandoned university after a year and a half and never returned.

To be sure, most dropouts do not become geniuses or success stories. But prominent among the dropout titans of recent history are Bill Gates (Harvard), Steve Jobs (Reed College), Mark Zuckerberg (Harvard), Elon Musk (Stanford), Bob Dylan (University of Minnesota), Lady Gaga (New York University), and Oprah Winfrey (Tennessee State). Jack Ma never went to college, and neither did Richard Branson, who dropped out of high school at age fifteen. Creative force Kanye West dropped out of Chicago State University at age twenty to pursue a musical career; six years later he released his first album to great critical acclaim and commercial success: The College Dropout (2004). The point is not to encourage dropping out but rather to observe that these transformative figures were somehow able to learn what they needed to know. Here successful people and geniuses share a common trait: most are lifelong learning addicts. It’s a good habit to have.

Finally, how might we nongeniuses cultivate a lust for learning beyond the obvious acts of reading, attending lectures, or finding a challenging vacation venue for next year? Here are some everyday ideas.

- Be open to new and unfamiliar experiences: Push yourself to do something that scares you. Let yourself get lost while wandering in a new city; you’ll see a lot of places you didn’t know existed.

- Be fearless: When in a new town, don’t call for an Uber—walk or take public transportation; you’ll learn about geography, history, and the local culture.

- Ask questions: When you stand in the “presenter mode” (as teacher, parent, or corporate leader), use the Socratic method. And when you are in the role of student or employee, don’t be afraid to reveal what you don’t know—instead, ask!

- Once you ask, listen carefully to the answer; you’ll learn something. Here we might all learn from a negative example: geniuses are generally not good listeners because they are usually too obsessed with their own vision of the world. Savvy successful people, however, know how to listen.

A WISE PERSON ONCE OBSERVED, “EDUCATION IS WASTED ON THE young.” But education doesn’t have to go only to the young. Today, young and old alike can learn independently, as the world has learned during the COVID-19 shutdown of 2020. Online Tech Ed platforms—such as Coursera (Yale and other universities), edX (Harvard and MIT), and Stanford Online—offer nearly one thousand high-quality courses to the general public, and most are entirely free. My own online Yale course, Introduction to Classical Music, now has more than 150,000 learners, and the median age of the participants is forty-four. Adult book clubs are similarly thriving, in part because it has never been easier to get access to just about any book that you might want to read, delivered in one day or even instantly by downloading an e-book to your Kindle, Nook, or iPad. “No professor has read more,” said Queen Elizabeth; “I ran out of books in the school library,” said Musk; “It’s an invitation to life, and it feeds you forever,” said Winfrey, in reference to reading and education. With modern technology at hand, the opportunity to self-educate, anywhere at anytime, is more robust and more diverse than ever. Compared to the geniuses of yore, we have it easy.