Sometimes it takes discipline to relax. And sometimes it takes discipline so as to focus, first to analyze a problem and then to get our “product” out the door. This applies to successful people as well as geniuses. We know that we must concentrate to come up with a solution, but then do we execute or procrastinate? Leonardo da Vinci had extraordinary powers of analytical concentration, as we will see. But once he saw the solution, he often lost interest and didn’t produce the product. That perhaps explains why he left us fewer than twenty-five completed paintings. The cartoonist Charles Schulz, who drew 17,897 Peanuts comic strips, was known for the hours that he would spend just doodling with a pencil, letting his mind wander. But then, according to his biographer David Michaelis, “Once he had an idea, he would work quickly and with intense concentration to get it onto paper before the inspiration dried up.”1 Whether arising from relaxed defocused musings or intense analytical concentration, ideas that have the capacity to change the world must be reified, verified, and publicized before they can have their transformative impact. Both analysis and execution require concentrated hard work.

ANALYTICAL CONCENTRATION PRECEDES EXECUTION. BEFORE PABLO Picasso executed with pen or brush in hand, he often analyzed using only eye and mind. Picasso’s muse during the 1940s, Françoise Gilot, recounted how he would intently analyze his favorite subject, the female body:

The next day he said, “You’d be better posing for me nude.” When I had taken off my clothes, he had me stand back to the entrance, very erect, with my arms at my side. Except for the shaft of daylight coming in through the high window at my right, the whole place was bathed in a dim, uniform light that was on the edge of shadow. Pablo stood off, three or four yards from me, looking tense and remote. His eyes didn’t leave me for a second. He didn’t touch his drawing pad; he wasn’t even holding a pencil. It seemed a very long time.

Finally he said, “I see what I need to do. You can dress now. You won’t have to pose again.” When I went to get my clothes I saw that I had been standing there just over an hour.2

Leonardo da Vinci would also just stand and stare. Indeed, he seems to have spent as much time analyzing the composition of The Last Supper (1485–1488) in the abbey of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan as he did executing it. As his contemporary the writer Matteo Bandello reported, “He would sometimes remain two, three, or four days without touching his brush, although he spent several hours a day standing in front the work, arms folded, examining and criticizing the figures to himself.”3 That concentration Leonardo called his discorso mentale (mental discourse).

Infuriated by the slow progress of The Last Supper, the abbot of the monastery complained to Leonardo’s patron, the duke of Milan. Called upon to explain his slow progress, Leonardo declared that “the greatest geniuses sometimes accomplish more when they work less, since they are searching for inventions in their minds, and forming those perfect ideas which their hands then express and reproduce from what they previously conceived with their intellect.”4 Atypical for Leonardo, once he had his “inventions” for The Last Supper securely in his mind, he continued to focus, now executing furiously. “He sometimes stayed there from dawn to sundown,” said Bandello, “never putting down his brush, forgetting to eat and drink, painting without pause.”

Similarly, Picasso would eventually execute his paintings, working as if possessed, according to this report from his longtime secretary, Jaime Sabartés:

Even while he is attending to his palette, he goes on contemplating the picture from a corner of his eye. The canvas and the palette compete for his attention, which does not abandon either; both remain within the focus of his vision, which embraces the totality of each, and both together. He surrenders body and soul to the activity which is his raison d’etre, dabbing the bristles of the brush in the oily paste of colour with a loving gesture, with all his senses focused upon a single aim, as if he were bewitched.5

NO MATTER WHERE HE HAPPENED TO BE, ALBERT EINSTEIN COULD concentrate in his own mental silo. A friend described the apartment in which Einstein, as a new father, worked in Basel around 1903:

The room smelled of diapers and stale smoke, and puffs of smoke arose every so often from the stove, but these things didn’t seem to bother Einstein. He had the baby on one knee and a pad on the other, and every so often he would write an equation on the pad, then quickly rock the baby a little faster as he began to fuss.6

Later that grown son said, “Even the loudest baby-crying didn’t seem to disturb Father. He could go on with his work completely impervious to noise.”7 According to Einstein’s sister Maja, the same might happen in the midst of a crowd: “In a large, quite noisy group, he could withdraw to the sofa, take pen and paper in hand, . . . and lose himself so completely in a problem that the conversation of many voices stimulated rather than disturbed him.”8

Sometimes Einstein’s powers of concentration led to comical results. Once during a speech at a reception in his honor, Einstein took out his pen and started to scribble equations on the back of his program, apparently oblivious to all the things being said about him. “The speech ended with a great flourish. Everybody stood up, clapping hands and turning to Einstein. Helen [his secretary] whispered to him that he had to get up, which he did. Unaware of the fact that the ovation was for him, he clapped his hands too.”9

Mozart had the same power to “get into the zone.” His wife, Constanze, recounted that during an outdoor lawn bowling party in 1787 he continued to work on the opera Don Giovanni, oblivious to all around him; when called upon to take his turn, he stood up, bowled, and “then went back to work without the speech and laughter of the others disturbing him in the least.”10 But how amused was Constanze in 1783 when her husband wrote his String Quartet no. 15, K. 421 at her bedside while she gave birth to their first child, Raimund? He would briefly comfort her but then return to writing his music.11

TODAY, CONCENTRATING IN THE MIDST OF CHAOS MAY REQUIRE mentally constructing a “fourth wall.” The expression derives from the theater, where actors are asked to build an imaginary barrier so as to separate themselves from the audience out front, and thereby stay within their own psychological space. Next time you are waiting at LaGuardia Airport or Heathrow or are packed in a middle coach seat on a noisy flight, try erecting your own fourth wall and finding therein your own Zen realm in which you are the only citizen. Within your own mentally imposed domain, you, like Einstein and Mozart, can work oblivious to all outside interference.

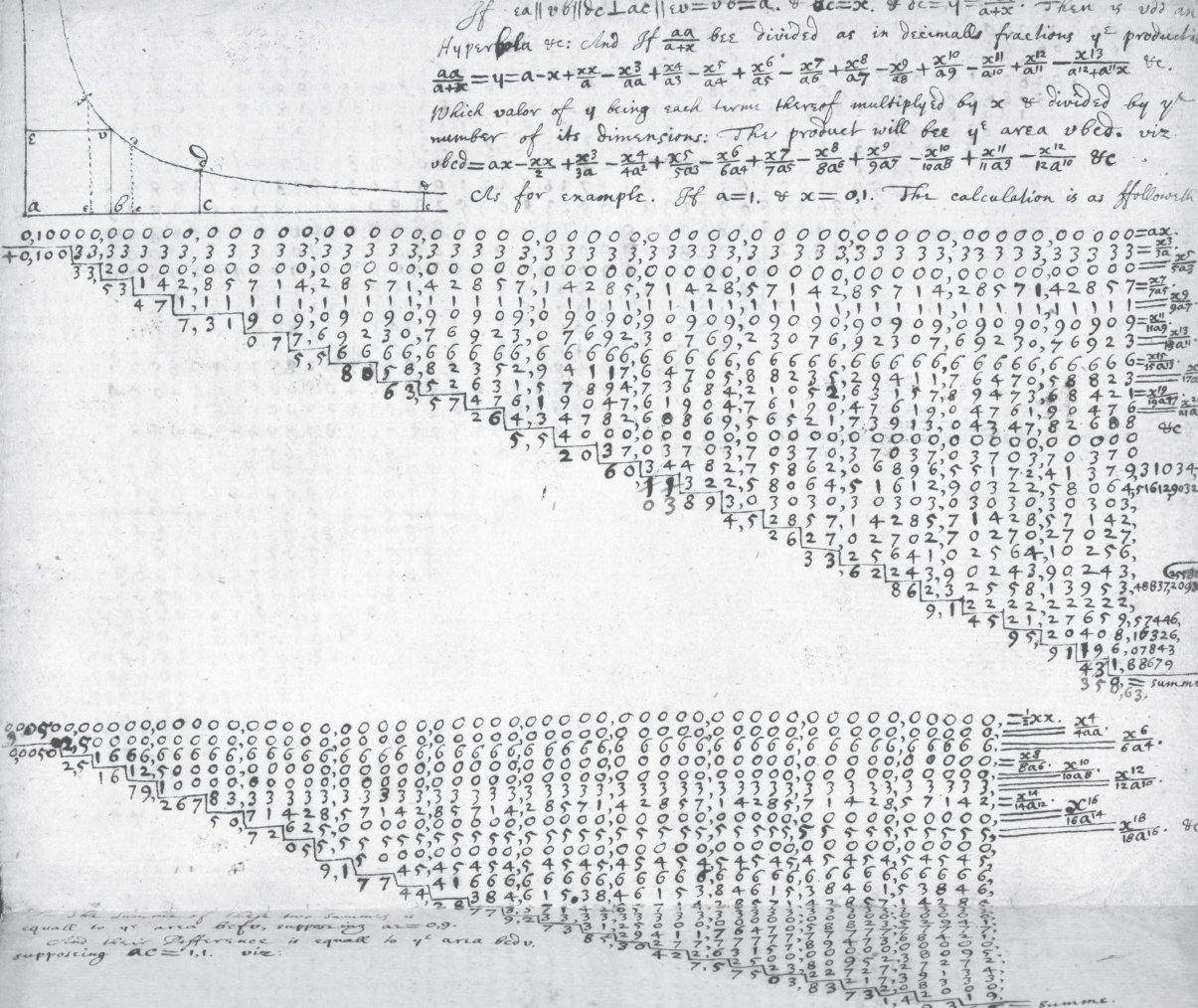

Isaac Newton’s powers of concentration seem to have bordered on mental disorder. His manservant Humphrey Newton (no relation) wrote, “So intent, so serious upon his Studies that he eat very sparingly, nay, oftimes he has forgot to eat at all, so that going into his Chamber, I have found his Mess untouch’d, of which when I have reminded him, would reply, Have I; & then making to the Table, would eat a bit or two standing, for I cannot say, I ever saw Him sit at Table by himself.”12 To appreciate Newton’s ability to focus, consider Figure 14.1. Here we see him working out the beginning of an infinite sequence: fifty-five columns of figures marching along in neat, tidy rows, and all done, as far as can be determined, entirely in his head. Another genius, the economist John Maynard Keynes, summed up Newton’s ability to concentrate: “I fancy his pre-eminence is due to his muscles of intuition being the strongest and most enduring with which a man has ever been gifted. Anyone who has ever attempted pure scientific or philosophical thought knows how one can hold a problem momentarily in one’s mind and apply all one’s powers of concentration to piercing through it, and how it will dissolve and escape and you find that what you are surveying is a blank. I believe that Newton could hold a problem in his mind for hours and days and weeks until it surrendered to him its secret.”13 As Keynes observed, when trying to concentrate, we all experience the way the object of thought can “dissolve and escape.” Concentration requires a good memory.

ROBERT HESS ARRIVED AS A FRESHMAN AT YALE IN 2011 AS THE highest-ranking U.S. chess player of native birth. He had achieved the title “international grandmaster” two years before at age seventeen. In 2008, the chess journalist Jerry Hanken called a recent Hess match “one of the greatest performances by an American teenager since the heyday of Bobby Fischer.”14 Being curious about freshman Robert, I tracked him down and invited him to join the Yale “genius class” on “chess day.” To make things interesting, I auditioned three other experienced players to do battle with Robert simultaneously—while he was blindfolded. Spotters knowing chess notation moved the pieces for him as he called out the moves (P to K4, for example). Students and visitors crowded around looking anxiously at the boards. Within ten to fifteen minutes each adversary was defeated. The crowd went crazy.

FIGURE 14.1: Newton calculating the area under a hyperbola to fifty-five decimal places by adding values from each term of an infinite series, ca. 1665. Newton apparently wrote his page, part of his development of calculus, while at home in Lincolnshire “quarantining” from the plague that then ravaged the university town of Cambridge (Additional Manuscript 3958, fol. 78v, Cambridge University Library, Cambridge, UK).

Cambridge University Library, MS Additional 3958, fol. 78v: Digital Content Unit

That was impressive. But more astonishing was what was to come. “Robert,” I said, “how good is your memory?15 How well do you remember those games?” “I remember all of them,” he said with polite nonchalance, and he wrote on the blackboard the succession of ten to twenty moves in sequence for each of the three games. “I could have done this against ten players blindfolded,” he said, not bragging but as a simple statement of fact. “Of course,” a student piped up, “he has a photographic memory.” “Think about it,” responded another dismissively, “he was blindfolded and couldn’t see a thing. What’s to photograph?” Maybe Robert can “photograph” what he sees in his mind.

Many great minds throughout history seem to have possessed a photographic or eidetic memory—the ability to recall an image after only seeing it once—and used it as a tool of concentration. Once, when in a tavern, Michelangelo argued with fellow artists over who could create the ugliest image. Michelangelo drew his way to victory and said he owed it to the fact that he had seen and could remember all the graffiti in Rome.16 Those around Picasso believed that he, too, had a photographic memory for visual images, for he once described an assumed-to-be-lost photograph in every detail, later to have his mnemonic powers validated when the image resurfaced.17 James Joyce was known to his Jesuit teachers at Clongowes Wood College as “the boy with the ink-blotter mind.”18 Elon Musk was called “genius boy” by his mother because, she said, he possessed a photographic memory.19 In 1951, the conductor Arturo Toscanini wanted the N.B.C. Symphony to perform the slow movement of Quartet no. 5 by Joachim Raff, but no score of the obscure ten-minute piece could be located in New York. So Toscanini, who had not seen the piece for years, laboriously wrote it out, note for note. Later, a collector of musical autographs found the original score and checked it against Toscanini’s manuscript, finding only one error.20

Few of us possess a photographic memory like the geniuses named above. Even the gifted have had to work to attain mnemonic prowess. Robert Hess had been playing chess since the age of five under the watchful eye of paid tutors; day after day he had practiced by memorizing standard openings, positions, and endgames, as well as famous matches throughout history. Leonardo da Vinci willfully worked to improve his memory. According to his contemporary biographer Giorgio Vasari, “He so loved bizarre physiognomies, with beards and hair like savages, that he would follow someone who had caught his attention for a whole day. He would memorize his appearance so well that on his return home he would be able to draw him as if he had him before his very eyes.”21 At night Leonardo would rest in bed, trying to re-create in his mind the images he had seen during the day.22 We can follow the spirit of Leonardo by engaging in mind-challenging activities such as playing chess or Sudoku, sight-reading a score for a musical instrument, or assembling something that requires following instructions sequentially and to the letter. According to Harvard Health Publishing, we’d all improve our memory by avoiding alcohol and exercising regularly, so as to increase blood flow to the brain.23 As Leonardo’s biographer Fritjof Capra reported, Leonardo himself regularly lifted weights.24

Averse to pumping iron? There is an alternate practical technique that we can all employ: set a deadline. Geniuses are intrinsically motivated, passionate about what they are doing. But sometimes even they benefit from last-minute external motivation to assure that the job gets done. Charles Schulz had to finish his cartoon before the next edition of the 2,600 newspapers in which his work was syndicated; Mozart had a theater rented and an audience arriving to hear Don Giovanni. Elon Musk has production quotas he has to meet for his Tesla automobiles; Jeff Bezos guarantees that your Amazon Prime package will be delivered in one to two days. Even imposing an arbitrary deadline on ourselves can enhance our concentration and help us remove the inconsequential.

STEPHEN HAWKING WAS SOMEONE WHO HAD THINGS BOTH CONSEQUENTIAL and inconsequential removed from him. Hawking has been called “the greatest genius since Einstein,”25 as well as “the genius in the wheelchair.” Hawking himself maintained that the latter designation was media hype, driven by the public’s thirst for heroes.26 To be sure, the public has always had a soft spot for the genius trapped in a wrecked body. Think of the Hunchback of Notre Dame, the Phantom of the Opera, and Alastor “Mad-Eye” Moody in Harry Potter—each a genius hidden behind a deformed exterior.

Hawking only seriously began to concentrate at age twenty-one—and only because he had to, due to the onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Before that year, he seems to have been an underachieving bon vivant. By his own admission, he did not read until the age of eight; in school he was only in the middle of the class academically; and in college he spent his time socializing, working only an hour a day.27 But in 1963, at the age of twenty-one, Hawking suddenly faced a literal deadline: he was given a diagnosis of ALS that came with a life expectancy of two to three years. Confined to a wheelchair, he had few distractions. By 1985, he had lost the ability to speak and was unable to communicate except through his computer. Of necessity, he focused on his chosen field, astrophysics. When I asked Kitty Ferguson, Hawking’s friend and principal biographer, whether Hawking’s isolation had enhanced his ability to concentrate, she offered this important insight: “I would say that his disability probably didn’t increase his capacity to concentrate, but it did increase his inclination to concentrate, finally to grow up, focus, and quit wasting time. As he once said to me, ‘What choice did I have?’”28

By the early 1970s, Hawking had lost the use of his hands. That posed a problem because all physicists do their thinking as they work through equations, writing endlessly on paper, blackboards, walls, doors, or almost any other flat surface—analytical concentration toggling with execution. To continue in that vein, Hawking developed a workaround: he would see the problem in his mind and hold it there, concentrating in a way similar to the way Newton had. A Nobel Prize winner and friend of Hawking, Kip Thorne, said, “He learned to do [math and physics] entirely in his head without writing things down. He did it by manipulating images of the shapes of objects, the shapes of curves, the shapes of surface, not merely in three-dimensional space but four-dimensional space plus time. What makes him unique among all physicists is his ability to do wide ranging calculations far better than if he had not had ALS.”29 Hawking confessed that in the midst of distractions, he, like Einstein, would focus by entering his own zone of focused thought: “Turning problems over in my mind has been my method of discovery for nearly half my life now. While all around me people have buzzed away deep in conversation, I have often been transported afar, lost in my own thoughts, trying to fathom how the universe works.”30 Kitty Ferguson summed up Hawking’s capacity to focus: “Few have Hawking’s powers of concentration and self-control. Few have his genius.”31 The master of black holes had managed to thrive in his own.

ON JULY 1, 2014, I HAD AN ISCHEMIC STROKE, AND MY WIFE rushed me to the hospital in Sarasota, Florida, where we currently live. Scans showed that I had (and still have) a completely blocked left interior carotid artery; attempts to clear it through an endarterectomy were pointless. For three days I was hooked up to wires in a hospital bed in my own black hole. I could think, but I could not speak. A virtual prisoner inside my body, I said silently, “Craig, this is serious. You are going to have to dig your way out of this. Think, concentrate, and pull your life together.” I started doing some mental exercises that I invented in an effort to reunite my short-term memory and speech, proceeding in order of increasing difficulty: (1) Say “blue bull dog” and remember the first word after you have finished the third; (2) Identify two composers who lived between Bach and Brahms; (3) Name three restaurants on Longboat Key from south to north; (4) Say all four syllables in the name of the road that runs from Tampa to Miami (Tamiami). Hour after hour I concentrated—what else was there to do? Whether or not this self-willed exercise contributed to a sudden turn of mind, I cannot say, but on the third day my blocked blood flow reversed itself, and thereafter, over a period of months, I gradually regained normal cognitive function. I was lucky. Of course my experience, although serious at the time, was trivial compared to Hawking’s ALS. Yet it did give me a glimpse of what it might have been like there inside his mental silo. “Keeping the mind active was the key to my survival,”32 he once said, and he lived more than fifty years longer than doctors had initially expected. Sometimes in life it is imperative to relax, defocus, and let your mind carry you away to original insights. But at other times, whether you are a genius like Hawking or a plodder like me, there are practical problems to be solved in space or elsewhere. At such moments, you must find the discipline to concentrate.

EVERY GENIUS HAS A TIME, PLACE, AND ENVIRONMENT FOR WORKING and getting the job done.33 You may call this “habit” (as I do in this book and as did Vladimir Nabokov and Shel Silverstein), “routine” (Leo Tolstoy and John Updike), “schedule” (Isaac Asimov, Yayoi Kusama, and Stephen King), “rut” (Andy Warhol), or “ritual” (Confucius and Twyla Tharp). The habits of these great minds are neither glamorous nor exalted. “Inspiration is for amateurs,” says the painter Chuck Close. “The rest of us just show up and get to work.”34

Just as every genius is different, so each has his or her own unique way of concentrating. The author Thomas Wolfe, standing six feet, six inches tall, wrote on top of a kitchen refrigerator beginning around midnight. Ernest Hemingway started in the morning, typing on his Underwood portable set on top of a bookcase in the annex to his Key West home. John Cheever would put on his only suit in the morning, as if preparing to join other professional men going to work. Descending in the elevator to the basement of his New York City apartment building, he would then take off his suit coat and write while leaning on storage boxes until noon. Then he would put his coat on again and ascend home for lunch.35

Intense concentration, in some cases, requires a break involving physical exercise. Victor Hugo would take a two-hour break and head toward the ocean, working out vigorously on the beach. Igor Stravinsky, if energy and concentration were flagging, would stand on his head for a short period of time. Nobel Prize winner Saul Bellow did the same—perhaps to increase blood flow to the brain. The choreographer Twyla Tharp, for whom physical conditioning was part of her creative process, went daily to the Pumping Iron Gym at 5:30 A.M. But as she said in her book The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life, “The ritual is not the stretching and weight training I put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. The moment I tell the driver where to go I have completed the ritual.” Having a disciplined ritual makes life simpler and increases productivity. “It’s actively antisocial,” Tharp said. “On the other hand, it is pro-creative.”36

Most geniuses create in offices, labs, or studios walled off from the outside world. Once inside his studio, painter N. C. Wyeth taped cardboard “blinders” to the sides of his glasses so as not to see beyond his canvas. Tolstoy locked his door. Dickens had an extra door built to his study to block noise. Nabokov, when writing Lolita, worked every night in the back seat of his parked car, “the only place in the country,” he said, “with no noise and no drafts.” Marcel Proust had his apartment walls lined with cork. The point of all this: geniuses need to concentrate. Einstein more than once encouraged fledgling scientists to get a job as a lighthouse keeper so as to “devote themselves undisturbed” to thinking.37

Call it a lighthouse or a safe house, all great minds have a space in which they get into the zone. The mystery writer Agatha Christie was often beset by social and professional interruptions, yet, as she recalled, “Once I could get away, however, shut the door and get people not to interrupt me, then I was able to go full speed ahead, completely lost in what I was doing.”38

Follow her lead but go one step further: Don’t interrupt yourself with diverting web searches or email. But do give yourself confidence and encouragement by placing marks of your previous accomplishments (diplomas, certificates, awards) in view, as well as portraits of your heroes or heroines. Brahms kept a lithograph of Beethoven above his piano. Einstein kept inspirational likenesses of Newton, Faraday, and Maxwell in his study; and Darwin had portraits of his idols—Hooker, Lyell, and Wedgewood—in his. The creative process itself is frightening—often “the great work” seems suddenly to be nothing of value—and simple tricks like these can help. With a ritual to fall back upon, you can get up and try again tomorrow. “A solid routine,” said John Updike, “saves you from giving up.”39

Thus, a final lesson for the rest of us from the geniuses of this book: to be more efficient and productive, create a daily routine for yourself that comes with a four-wall safe zone for constructive concentration. Get to the office, or to your study or studio, and secure some space and time for interior thinking. Of course, give yourself access to a wide array of opinions and information, but remember that at the end of the day, you alone are responsible for synthesizing that information and producing something. We need successful people to make the world function well today. We need geniuses to ensure that it will function better tomorrow.