WHILE WE were doing our lessons that night, Mother said, “Didn’t Fred Aultland offer to lend you horses until ours were well again?”

It was a few minutes before Father answered. “Yes, Mame, he did, but . . . what is that one you quote about being neither a borrower nor a lender? Fred’s a fine fellow, but I don’t want to start borrowing from the neighbors, and then, too, he’ll need all his horses at plowing time when I’ll have to have three.”

Mother said, “I just don’t see how we can take out fifty dollars for another horse, and more to buy harness for it, until we have something to sell.” Father didn’t say anything except that he’d talk to Mr. Cash.

Mr. Cash was an old horse trader-peddler, who used to come by our place every couple of weeks. He had an old covered wagon filled with everything from safety pins to rolls of secondhand barbed wire, and he usually had three or four old horses tied to the tail gate.

He came by the next Sunday, and Father haggled with him for over an hour. I was out by the wagon when they finally made the deal. Father had looked the different horses over from teeth to hoofs. He had both hands in the hip pockets of his overalls and was looking at an old bay mare on the off side. “How much for Grandma?” he asked.

Mr. Cash said he had paid twenty-five dollars for her, but in the end he let Father have her for seventeen-fifty, and threw in a collar, and hames with chain traces. When we were leading her to the barn, I noticed that she dragged one fore hoof. Father said it was because she had been foundered. Because she walked so slow, Mother named her Nancy Hanks, after a famous race horse.

Mother let me wear my overalls and blue shirt to school Monday morning. Grace fiddled along all the way, hunting for some certain kind of cactus. We got in just after the bell rang. Freddie’s eye was blacker than mine and his lips were still puffed. I had wanted to get there early enough to see if I could lick him again before school began, but I had to wait for morning recess.

Everybody knew Freddie and I were going to fight again at recess time. We made faces at each other every time Miss Wheeler had her back to the class. What I didn’t know was that Freddie had a deal with Johnnie Alder to help him lick me.

Johnnie was in the fifth grade, and nearly as big as Willie Aldivote. As soon as we got out near the carriage shed, Freddie and Johnnie both jumped on me. I was sure I was done for until Willie sailed in, too.

I always liked Willie Aldivote best of the boys. He was the second biggest in school; he was twelve, and was in the sixth grade in number work. He was the one who had the yellow-spotted donkey, and he could ride like everything. He had never been mean to me.

Willie told Johnnie, “If you’re going to help Freddie, I’ll help Molly,” and the fight was on. It was really two fights for a little while. Then, when Johnnie was good and licked, Willie kept Freddie from holding me by the hair with one hand while he punched me with the other.

After that I had better luck, and before the bell rang for the end of recess, Freddie had both arms up over his face again. Then he did something that I ought to have loved him for. He said, “There ain’t meat enough on him to hit, that’s why I can’t lick him. He’s just a sackful of old spikes, and I hurt my own hands worse’n I hurt him every time I punch.”

At noon I ate my lunch with all the rest of the fellows, sitting right between Willie Aldivote and Rudolph Haas. After we finished eating, Willie said, “Come on, Rudy, let’s teach Spikes how to really ride that jackass.” Nobody will ever write a poem that will sound as good to me as that did. I knew I wasn’t going to be Molly any more, and I’d have tried to ride a rhinoceros if they’d said so.

They got straps off one of the harnesses and a piece of good, stout cord. After they’d buckled the straps real tight around the donkey, Rudy held him by the ears while Willie put me on and tied my feet together with the cord. He ran it snug between them, under the donkey’s belly. Willie told me not to be scared, to squeeze tight with my knees and watch the donkey’s head so I could lean way back when he put it down to kick. I grabbed hold of the straps with both hands, and Rudy let him go.

For what seemed an hour, but was probably ten seconds, things were happening too fast for me to keep up with them. I tried to watch his head and lean back every time it went down, but it was bobbing so fast I lost the beat. My head snapped back and forth as though it were tied on with rubber, and I bit my tongue. My head rang so I couldn’t even hear Grace yelling—she had come running to pick up the pieces when I got killed—but I was still on top when he stopped, and I’d had fun. After school, Willie let me ride behind him on the donkey as far as our corner, and Grace was so proud of me that she promised not to tell Mother.

Three or four days after we got Nancy Hanks, Grace and I came home from school through our west field, so I could show her where Bill and Nig had fallen off the trestle. There were twelve or thirteen long crossties in the bottom of the gulch, and I told Grace that Father had said for me to drag them home as soon as we got another horse. I had been riding Willie’s donkey every day, and thought I’d be able to handle any horse.

I guess I’d made up too many stories before. Grace didn’t believe me, and told Mother about it the minute we got home. I should have admitted to Mother right then that it was only a story, but I was sure she’d spank me if I did. The more I thought about hauling those ties with Nancy, the more I wanted to do it. And, since I was going to get a spanking anyway, I thought I might just as well have the fun of trying. So I swore up and down that Father did tell me. He had gone to Denver after another load of bricks, and I was sure I could have a crosstie home before he got back. Then he would probably be proud enough of me so that I wouldn’t get spanked at all.

Mother had to help me put the collar and hames on Nancy, because they were heavy and the collar didn’t have any buckle at the top. You had to put it over her head upside-down, and then turn it around. I never heard Father criticize Mother, and that was the only time I ever heard her criticize him. She put her hands on her hips and buttoned her mouth up tight, then she said, “I don’t know what in the world this ranching has done to your father! Insisting that you wear overalls to school and be permitted to behave yourself like a guttersnipe! And now! Hmfff! Sending a little eight-year-old boy off to haul logs with a new, untried horse!”

The crossties didn’t haul as easy as I thought they would. I forgot to take anything along for hitching them to Nancy’s singletree, and had to use an old piece of barbed wire. I was walking on the downhill side of the crosstie when we tried to go up over the bank at the head of the gulch. Suddenly the tie started to roll toward me and I had to dive out of the way. I skinned my nose and the barbed wire tore a big hole in my overalls, but the tie missed me, and Nancy seemed glad to stop and rest. I was still trying to haul it up over the bank when it got dark, and I was afraid Father would get home before I did. It would be better to go right home and tell Mother I’d lied. If she spanked me first, he probably wouldn’t give me another one right on top of it.

Mother didn’t spank me, though. She gasped, and looked at me as if I’d been a rattlesnake ready to strike. Then she made me stand with my face in a corner. I stood there while the rest of the youngsters had their supper and went to bed, and for at least an hour afterward while Mother sat at the table and read the Bible. I knew what she was reading, because I heard her take it down from the lamp shelf. There wasn’t any clock in the kitchen, and the only sound was the thumping of my own heart.

At last I heard Father drive into the yard, and listened to every sound as he put the team away and came to the house. He stood in the open doorway for a moment before he spoke. When he did, his voice was very quiet. “What has happened, Mame?”

It was a full minute before Mother said anything. And then her voice was as quiet as Father’s. “Charles, the time has come when this boy must have a father’s firm hand. I am appalled by the degeneracy he has shown since we left East Rochester.”

I had never heard Mother’s voice like that, and I had never heard her call Father “Charles.” I thought my heart would pound itself to pieces while she was telling him what I had done. Hard as Father could spank, he never hurt me so much with a stick as he did when Mother stopped talking. He cleared his throat, and then he didn’t make a sound for at least two full minutes.

When he spoke, his voice was deep and dry, and I knew he must have been coughing a lot on the way home. “Son, there is no question but what the thing you have done today deserves severe punishment. You might have killed yourself or the horse, but much worse than that, you have injured your own character. A man’s character is like his house. If he tears boards off his house and burns them to keep himself warm and comfortable, his house soon becomes a ruin. If he tells lies to be able to do the things he shouldn’t do but wants to, his character will soon become a ruin. A man with a ruined character is a shame on the face of the earth.”

He waited until his words had plenty of time to soak in, then he said, “I might give you a hard thrashing; if I did, you would possibly remember the thrashing longer than you would remember about the injury you have done yourself. I am not going to do it. There were eighteen crossties in the gulch yesterday, and the section foreman told me they were going to replace twenty more. Until you have dragged every one of those ties home, you will wear your Buster Brown suit to school, and I will not take you anywhere with me.”

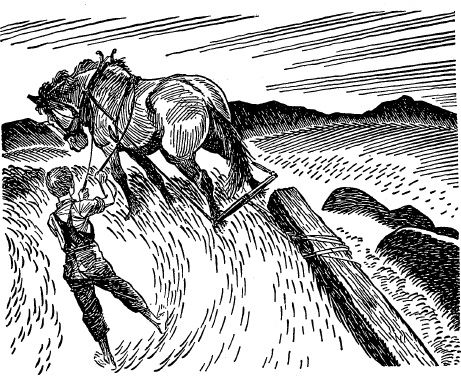

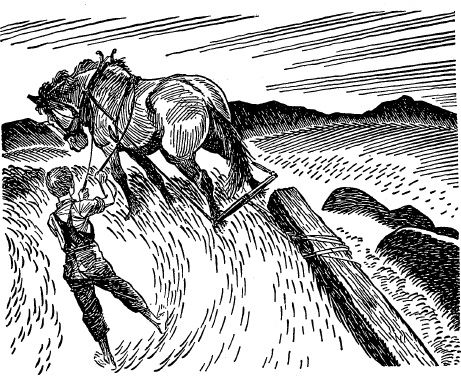

It was half a mile from the house to the gulch. Father showed me how to hook onto the ties with a chain, and how to pull them up through the head of the gulch. By getting up early, I dragged one tie home each morning and two after school. With a half dozen on Saturdays, I had the job done in a couple of weeks.

It was a tough two weeks. I was sure I would become Molly again for wearing the Buster Brown suit to school; I think Grace saved that by telling everybody what a bad boy I was. Then, too, the weather turned windy and cold. The gulch half filled with dry tumbleweeds that scratched me when I dug through them to get the ties. But worst of all, Mother got a song in her head. When that happened, she would sing the same tune over and over and over, for a week at a time. That time it was “The Bird with a Broken Pinion.” I don’t think she was singing it just for me, but I couldn’t go into the house without hearing about “a young life broken by sin’s seductive art,” or that “the soul that sin hath stricken never soars so high again.” It made me think a lot, as I walked along behind Nancy and a dragging crosstie, about the permanent damage I had already done to my character.