RATING:

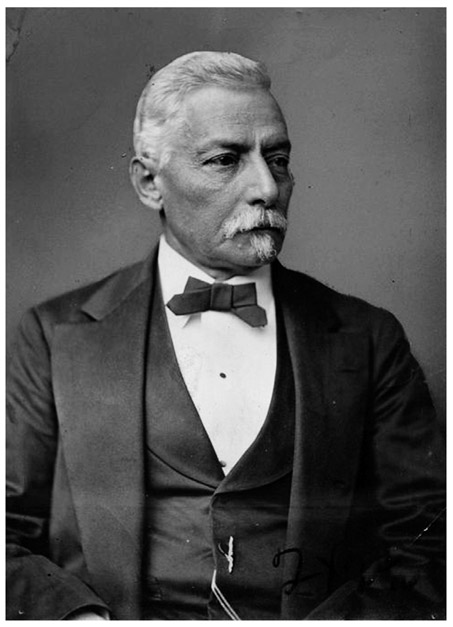

P. G. T. Beauregard. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION

The first general officer of the Confederacy, P. G. T. Beauregard was certainly well below the level of Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, Stonewall Jackson, and Nathan Bedford Forrest, yet he may be seen as the archetypal Confederate commander—in heritage, appearance, manner, popular appeal, grandiose vision, and theatrical manner. While some have dismissed him as something of a blowhard, others have seen his spasms of overheated battlefield rhetoric as inspiring (they sometimes were) and his flair for the dramatic as quite effective (as it was at the “Siege” of Corinth). He was impulsive, too often animated by an anachronistic sense of honor, poorly disciplined, weak in organization and logistics, sometimes wanting in tactics, and unrealistic in his formulation of broad strategy (though unshakable in his conviction that he was right), yet he was often an effective leader of men, a general capable of winning the confidence and cooperation of civilians (especially in Charleston), and a brilliant engineer, whose work on Confederate fortifications was more valuable than a field army corps. In short, his was a contradictory nature, and he combined an idiosyncratic unreliability with unprecedented longevity in command.

Principal Battles

PRE–CIVIL WAR

U.S.-Mexican War, 1846–1848

CIVIL WAR

For many, P. G. T. Beauregard—as a West Point cadet, he thought the first three of his names sounded too French and decided to use his initials instead—was and remains the very image of a Southern general. His florid mustache and neat, almost vestigial goatee, trimmed in the “imperial” fashion of Napoleon III, his chiseled jaw, a fine nose verging on aquiline, the high, broad forehead, his impeccably tailored uniforms, his obsession with “honor” (to the point of dueling), and the pride he took in counting himself a child of the Creole aristocracy, all were and are still part and parcel of the magnolia and moonlight picture. If all this seems too superficial to make Beauregard a truly meaningful icon of the Southern cause, the fact is that most icons are, by their nature, superficial, but Beauregard did have considerable substance as well.

He never wavered in his loyalty to his native state, Louisiana, although he was often at odds with the Richmond government, especially President Jefferson Davis. He served in the entire war. It was he who ordered the conflict’s first shots, against Fort Sumter on April 12–13, 1861; he played a major role in the first major battle of the war, First Bull Run on July 21, 1861; and he fought in both principal theaters of the war, serving from the very beginning to the bitter end, joining Joseph Johnston and the Army of Tennessee to fight William T. Sherman in Georgia and the Carolinas. Photographs of Beauregard before, during, and after the war reveal nary a hint of a smile, but neither do they suggest much pain. Unlike a number of his even more illustrious contemporaries in gray, his service was never interrupted by a serious wound, and, of course, he lived through it all, the war that his command had begun. He seemed never to regret any of it.

Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard was born on May 28, 1818, but he might just as well have emerged from the pages of some romance novel set in the deep South. His home was a sugarcane plantation called “Contreras” in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, twenty miles outside of New Orleans. He was the third of seven children—three brothers, three sisters—in the French-Spanish Creole family of Jacques Toutant-Beauregard and Hélène Judith de Reggio Toutant-Beauregard.

The Beauregards raised their children to be French men and women. Pierre Gustave attended a French-speaking private school in New Orleans until his eleventh year, when he was put on a train to New York City to continue his education at a preparatory school run by former officers of no less a figure than Napoleon. The boy was twelve before he spoke a word of English. And that was just fine with his parents, who, however, were appalled when he came back from his Napoleonic education with a powerful desire to become a military officer. They forbade it, they said, only to discover the full depth and breadth of the stubborn will of their boy—the same unyielding, unbending personality that would sustain him in the Civil War from its very beginning to its very end. In the end, they, not he, surrendered, and Jacques Toutant-Beauregard called in a political favor to secure an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The boy—and at nearly sixteen he was a boy—was enrolled in March 1834.

Despite his plantation background, the continual indoctrination as a member of the aristocracy, his belated acquaintance with the English language, and his own willful pride, young Beauregard got along surprisingly well with his classmates, who found him charming, affable, and doubtless appealingly exotic, if perhaps a trifle aloof. That he converted Pierre Gustave Toutant to initials at this time, often dropping the P altogether and calling himself “G. T. Beauregard,” suggests that he made an effort to fit in. His classmates showered him with affectionate nicknames, including “Little Creole” and “Little Frenchman” (he stood five-foot-seven, not short for the era, but his delicate brown features made him look smaller) and “Little Napoleon.” Future Confederate luminaries became close friends, including Jubal Early, Richard Ewell, and Braxton Bragg, but so did such figures of the Union as Irvin McDowell (against whom he would be pitted at First Bull Run), Joseph Hooker, and William Tecumseh Sherman. He excelled in his studies and was a favorite among his teachers, including artillery instructor Robert Anderson, who saw in him the makings of a fine artilleryman. Anderson would be the Fort Sumter commandant whose fate it became, in April 1861, to discover just how capable an artillerist his former student was.

Fellow cadets recalled “G. T. Beauregard” as a very fine horseman and athlete who did very well academically—he would graduate second in the Class of 1838—and a few spoke of something more, a detail befitting the aura of romance that hung about him. It was rumored that he fell in love with Winfield Scott’s daughter, Virginia, and that the two even became secretly engaged, only to meet with the general’s objection that they were too young to marry. The story goes that they separated but wrote to one another faithfully, yet neither received the other’s letters. It was years later that Beauregard discovered that Virginia’s mother had intercepted her daughter’s outgoing billets-doux as well as his incoming missives. By that time, however, he had married another woman. The story has never been confirmed, but it was told over and over by those who soldiered with Beauregard early in his career.

At the top of his class, Beauregard naturally requested assignment in the Corps of Engineers and was immediately dispatched to work on the most ambitious and important projects the army had in hand, including Fort Adams at Newport, Rhode Island. That a newly minted engineer should have received so coveted an assignment testifies to the early esteem in which he was held. In 1839, promoted to first lieutenant, he was sent to Pensacola, Florida, to build coastal defenses there, and was shipped off next, in 1844, to make improvements at Fort McHenry, Baltimore Harbor. This assignment introduced him to Baltimore high society, and the pro-Southern gentry of that city feted the handsome lieutenant lavishly.

His Baltimore interlude was all too brief. In February 1845, he was sent to his native Louisiana to construct and improve the Mississippi River forts. Here the dark side of the Southern gentleman was revealed. A dispute with a Lieutenant John Henshaw turned ugly, becoming what men of Beauregard’s turn of mind liked to call an “affair of honor,” and Beauregard challenged the man to a duel. The weapons of choice were shotguns. Fortunately for both men, the local sheriff got wind of the duel and arrived on the “field of honor” just in time to arrest the pair before a shot was fired.

Perhaps just as fortunate was the arrival of the U.S.-Mexican War, which took Beauregard out of Louisiana and opened to him a much larger field of honor. He was assigned to Winfield Scott’s army as an engineer serving directly under the general’s chief engineering officer, Captain Robert E. Lee, and alongside another top-performing West Point graduate, Lieutenant George Brinton McClellan.

Beauregard was in the thick of the action at the Battles of Contreras (August 19–20, 1847) and Churubusco (August 20), his performance in these contests earning him a brevet to captain. With Lee, he was credited for plotting out the path by which Scott’s army reached Mexico City. Indeed, the officers gathered with Scott praised young Beauregard’s eloquence in persuading the commanding general to change certain aspects of the assault plan against Chapultepec. At the battle for that fortress (September 12–13, 1847), the culminating struggle for the Mexican capital, he was wounded in the shoulder and thigh, received the personal thanks of General Scott (“Young man,” Old Fuss and Feathers reportedly said, “if I were not on horseback I would embrace you”), and a brevet to major.

Despite his wound, Beauregard made certain that he was among the very first officers to enter Mexico City on September 15. But he was rankled by the fact that Lee received three brevets—to colonel—to his two for the reconnaissance and tactical planning performed in connection with the assault on Chapultepec. Beauregard made no secret of his opinion that he had undertaken far more hazardous and important work than Lee, or any other officer, for that matter.

After the war, in 1848, Beauregard took charge of “the Mississippi and Lake defenses in Louisiana” for the U.S. Army Engineer Department—though he often traveled far outside of the area, repairing and expanding forts throughout the South and building new ones. He also supervised dredging and digging projects to improve the shipping channels at the mouth of the Mississippi River and even invented and patented a “self-acting bar excavator,” which was an aid for ships in clearing sand and clay bars. Beauregard pursued this engineering work for a dozen years following the war with Mexico. During this time, he also restlessly struggled to gain a foothold in Democratic politics. When his first wife died in 1850, he remarried a planter’s daughter named Caroline Deslonde, sister-in-law of Louisiana’s powerful senator John Slidell. This connection, largely passionless, gave Beauregard entrée into the party’s inner circle, and he plunged into the 1852 presidential campaign of Franklin Pierce, who had been a general in the U.S.-Mexican War. This brought a handsomely paid patronage appointment from President Pierce, who named Beauregard—still a serving U.S. Army officer—superintending engineer of the New Orleans Federal Customs House. It was no sinecure, but a genuine engineering challenge. Built in 1848 on swampy Louisiana soil, the edifice was fast sinking. From 1853 to 1860, while he held the job, Beauregard devised and supervised successful procedures for saving the building.

None of this, however, was sufficient diversion for Beauregard, who, like many other peacetime army officers, became intolerably bored. Toward the end of 1856, he notified the Engineer Department that he intended to travel to Nicaragua to join William Walker, the self-described “gray-eyed man of destiny,” who had led a “filibustering” campaign in Central America and managed to seize control of the Nicaraguan government. Walker had dangled before Beauregard an offer to serve as his number two in command of his military forces. General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, among others, managed to talk Beauregard out of his decision to go—which was a good thing, since Walker’s reign proved brief. The gray-eyed man of destiny was destined to execution by Honduran firing squad on September 12, 1860.

In 1858, Beauregard took a stab at elective office for himself, making a narrowly unsuccessful run for New Orleans mayor. By this time, as the nation’s slide toward civil war accelerated, he made no secret of his Southern sympathies, although he did not actively oppose Abraham Lincoln or campaign for any other candidate in 1860. Perhaps he believed that doing so would damage his prospects for obtaining an appointment as superintendent of West Point. Senator Slidell called in favors, and Beauregard was duly installed at the academy on January 23, 1861.

By this time, secession was in full swing, and his office was quickly overrun with Southern cadets who asked him whether and when they should resign from the academy. “Watch me,” Beauregard replied to them, “and when I jump, you jump. What’s the use of jumping too soon?”

As it turned out, he was never given the opportunity to jump. Five days into his new job, Louisiana seceded and his own orders to report to West Point were rescinded. He was kicked out, having set a record for the shortest tenure as academy superintendent that, understandably, has yet to be broken. Although historians and others have marveled that Beauregard had been named superintendent in the first place, given his outspoken Southern sympathies, he himself protested that his sense of honor had been offended by the dismissal, which (he wrote to the War Department) had cast “improper reflection upon my reputation” because no hostilities had actually begun. He was further outraged that the War Department refused to reimburse him for the $165 he claimed as travel expenses from West Point back to his home in New Orleans. Even after he resigned his commission, which he did several weeks after settling back home, he continued to pepper the War Department with demands for reimbursement. In the meantime, he advised local authorities on how to strengthen Forts St. Philip and Jackson, which guarded the Mississippi River approaches to New Orleans.

Beauregard had outsized ambitions concerning how he would serve the Confederacy—and how it would serve him. He had designs on being named commander of the Louisiana state army and was crushed when the state legislature appointed Braxton Bragg instead. As a sop to Beauregard, Bragg offered him a colonelcy in the state force, to which Beauregard indignantly responded by enlisting as a private in the Orleans Guards, a private militia battalion made up exclusively of Creole planter-class aristocrats like himself. This, however, was a mere gesture. He assiduously worked his connection with Slidell and, through him, reached President Jefferson Davis in the hope of being given a top command in the projected Confederate States Army. Now it was Bragg’s turn to be consumed with envy, as he was assailed by rumors that Beauregard was indeed about to be appointed general-in-chief.

Davis, however, had other plans for Beauregard. Summoning him to Montgomery, Alabama, the initial capital of the Confederacy, he offered him the rank of brigadier general—a satisfying leap from his last U.S. Army rank of major—and assigned him command of Charleston’s defenses. Davis was particularly concerned about the presence of the federal forts, especially Fort Sumter, in Charleston harbor, and he saw in Beauregard the kind of engineering background the job required, together with the Creole plantation credentials and aristocratic bearing that would impress the upper crust of Charleston. Officially commissioned in the Provisional Army of the Confederate States on March 1, 1861, P. G. T. Beauregard became the first general officer of the Confederacy.

Fort Sumter under attack. HARPER’S ILLUSTRATED WEEKLY

He arrived in Charleston on March 3, called on Governor Francis Wilkinson Pickens, then toured the harbor defenses. He saw immediately that a great deal had to be done, especially with regard to the positioning of guns. Gratified by the tumultuous reception the people of Charleston gave him, he was determined to secure their goodwill and took a comradely approach to recruiting local volunteers and enlisting them in the hard work of reorganizing the defenses. Accepting him as one of their kind, the locals cooperated with zeal, deploying guns under Beauregard’s direction in batteries at Morris, James, and Sullivan Islands, Mount Pleasant, and Forts Moultrie and Johnson, all drawing a bead on Fort Sumter.

Beauregard also initially approached Major Robert Anderson, his West Point artillery instructor and now commandant of Fort Sumter, with similar courtliness and professional camaraderie, even sending him and his fellow Sumter officers cases of vintage brandy, good whiskey, and fine cigars. Anderson returned them all.

On April 11, 1861, Beauregard put Colonel James Chestnut, a prominent South Carolina politician, and another man in a rowboat and sent them out to the fort under a flag of truce with a personal note to Anderson, again calling for his surrender and promising in return that all “proper facilities will be afforded for the removal of yourself and command, together with company arms and property, and all private property, to any post in the United States which you may select. The flag which you have upheld so long and with so much fortitude, under the most trying circumstances, may be saluted by you on taking it down.”

Asking the messengers’ indulgence, Anderson composed a careful and courteous reply to his former pupil. The demand, he wrote, was one “with which I regret that my sense of honor, and of my obligations to my government, prevent my compliance.” As he handed over the reply, he confided to the envoys: “Gentlemen, if you do not batter us to pieces, we shall be starved out in a few days.”

Just before one o’clock on the morning of April 12, 1861, Chestnut, with three other men, again rowed to the fort to advise the commandant that Beauregard would continue to hold his fire on condition that Anderson provide a firm date and time for his withdrawal from Fort Sumter. After a long conversation with his officers, Anderson, at 3:10 a.m., handed Chestnut his written reply. He would evacuate by April 15—unless he received orders to the contrary from “my government.” Chestnut, on whom Beauregard had conferred plenipotentiary authority, told Anderson that his conditions were unacceptable, and, right there and then, he scrawled a declaration warning him that the bombardment of Fort Sumter would commence in one hour. With this, he rowed away.

Shortly before 4:30 that morning, Beauregard ordered Captain George S. James to fire a signal gun as the command for the general barrage to begin. A Lieutenant Henry Farley, commanding a two-mortar battery on James Island, fired precisely at 4:30. This was the first shot of the war. For that entire day, the bombardment was unceasing and continued into Saturday, April 13, before Anderson, having decided that duty and honor were amply satisfied, lowered the Stars and Stripes. Beauregard ordered an immediate cease-fire. Fort Sumter had taken some four thousand incoming rounds—astoundingly, without a single casualty.

Hailed throughout the South as the “Hero of Fort Sumter,” Beauregard answered President Davis’s summons to the newly established capital of Richmond, Virginia, and was given command of the “Alexandria Line,” the defensive forces organized to repel an anticipated attack by West Point classmate Brigadier General Irvin McDowell.

Beauregard took two approaches by way of preparation. The first was to formulate a plan to consolidate the troops commanded by General Joseph E. Johnston in the Shenandoah Valley with his own Alexandria Line. His objective was not merely to defend his position at the Manassas rail junction, but to mount a counteroffensive against McDowell’s troops and against Washington, D.C., itself. The second approach was an exercise in what modern armies call psyops—psychological operations. Rising to a height of inflammatory hyperbole, Beauregard published a warning to the people of Virginia that a “restless and unprincipled tyrant has invaded your soil.” He accused Abraham Lincoln of abandoning all “constitutional restraints” to throw “his abolition hosts among you, who are murdering and imprisoning your citizens. . . . All rules of civilized warfare are abandoned” by barbaric men whose “war cry is ‘Beauty and booty.’”

Both approaches struck fire. Johnston, senior to Beauregard, bowed to his battle plan, and throughout Virginia, the people were roused to defend their “sacred soil.” Only Jefferson Davis, it seems, was plagued with doubt. Beauregard’s plan appeared to him to be an untenable stretch that ignored logistical realities. (This assessment would prove to be his response to Beauregard’s strategic contributions throughout the war.) Nevertheless, on this occasion, Davis, like Johnston, acquiesced in the brigadier general’s plan.

The battle began early on July 21. The plans of both McDowell and Beauregard called for envelopment of the enemy, but McDowell got the jump on Beauregard by menacing his left flank. Stubborn as always, Beauregard at first paid little attention to this as he maneuvered to make an attack from his own right flank until the more experienced Johnston persuaded him to devote his attention to his threatened left at Henry House Hill. Thus alerted, Beauregard turned over to Johnston the overall coordination of the battle while he personally rallied the troops at the point of contact. Beauregard rode down to the front lines, exposing himself to enemy fire as he brandished regimental colors and exhorted his men to action. In this way, he managed to hold the line at Henry House Hill, buying time for all of Johnston’s troops to arrive from the Shenandoah Valley. Fully reinforced, Beauregard and Johnston launched a counterattack that turned the tables on McDowell, routing the Union forces and sending them into headlong retreat to Washington.

Although Beauregard had drawn up the original plan, he quickly yielded overall direction of the battle to Johnston while he rode off to play the part of the romantic, dashing front-line general. There can be no denying that his display was effective—not only in rallying the troops, but in snatching all the glory for himself—but the battle, as fought, was largely the work of Johnston. For his part, Johnston was extraordinarily generous, recommending on July 23 the promotion of Beauregard to full general. Davis accepted the recommendation but soon regretted his decision as the volume of talk increased touting the hero of Fort Sumter and Manassas as his most desirable rival in the popular election of a Confederate president (Davis’s appointment had been provisional) scheduled for November. The friction between the two men increased during the winter lull in combat as Beauregard pushed for an invasion of Maryland to position the army for a rear and flanking attack on Washington. Even as Davis criticized Beauregard for having failed to follow through on his promised attack against Washington after Bull Run, he rejected the Maryland invasion as impractical. Affronted, Beauregard requested immediate reassignment to New Orleans but was refused. He then fell into dispute with other officers and with the Confederate secretary of war. He carried these arguments into the newspapers, using their pages to charge that the failure to exploit the Bull Run victory had been the result of President Davis’s interference.

Davis was in a tough spot. Beauregard had made himself intolerable, but the president dared not fire the hero of two major battles. Instead, he pushed him out west, to Tennessee, where, on March 14, 1862, he was assigned as second-in-command under General Albert Sidney Johnston (no relation to Joseph E. Johnston) in the Army of Mississippi.

Albert Sidney Johnston welcomed the arrival of Beauregard. He was in a perilous position, having been forced into retreat to Alabama after Ulysses S. Grant had taken Forts Henry and Donelson. Both Johnston and Beauregard understood that the critical task now was to engage Grant again before he could link up with the forces of Don Carlos Buell and attack Corinth, Mississippi.

Like Joseph E. Johnston, A. S. Johnston was senior to Beauregard, and, also like J. E. Johnston, he yielded to him in planning the surprise attack on Grant’s camp at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, near a church called Shiloh. Insofar as the plan was daring—a massive frontal assault—it was admirable. But poor organization undermined it. Beauregard threw each corps successively against the whole of Grant’s line instead of assigning a portion of the line to each corps. Although the resulting attack was fierce, it was confused and inefficient. On April 6, the Confederates came close to annihilating Grant, but after A. S. Johnston was mortally wounded late in the afternoon, the assault faltered. By nightfall, Beauregard, now in full command, ordered a withdrawal, which gave Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman the time they needed to regroup with reinforcements from the just-arrived Buell. Grant’s counterattack on April 7 forced Beauregard to fall back on Corinth, Mississippi. What had begun as a great Confederate victory-in-the-making ended in a costly defeat.

After Shiloh, Major General Henry W. Halleck decided to assume field command from Grant but then moved so slowly against Beauregard’s position at Corinth that the Confederate general had plenty of time to withdraw, on May 29, to Tupelo, Mississippi, covering his exit with a clever theatrical ruse—running empty trains back and forth and ordering his men to cheer with each “arrival,” thereby giving Halleck the impression that he was being heavily reinforced.

Most historians view the outcome of the “Siege” of Corinth—an assault on an empty town—as a Union humiliation; however, Davis chose to interpret Beauregard’s withdrawal as dishonorable because it had happened without a substantial fight, and when Beauregard followed this by taking sick leave without securing permission, the Confederate president replaced him as Army of Mississippi commander with General Braxton Bragg.

Not to be beaten by Halleck or Davis, Beauregard rallied friends in the Confederate Congress to petition Davis to restore his command. “If the whole world were to ask me to restore General Beauregard to the command which I have already given to General Bragg,” Davis wrote in reply, “I would refuse it.” He then ordered Beauregard back to Charleston to command the coastal defenses of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Given Beauregard’s engineering and artillery qualifications, it was a reasonable personnel decision. Beauregard, however, took it as an insult, nothing more or less than a way of high-handedly depriving him of a field command. But to his credit, he did not waste time pouting and performed brilliantly in defense of Charleston against naval and land assaults in 1863. Accurate and devastating coastal fire repulsed Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont’s bid to retake Fort Sumter on April 7, 1863, and land and sea attacks from July to September 1863 were all beaten off.

Beauregard the engineer embraced innovation, endorsing experiments with torpedoes (naval mines), with torpedo-rams (small ramming vessels fitted with a projecting spar torpedo, intended to blast a hole through the enemy ship’s hull below the waterline), and most famously with the submarine H. L. Hunley—an ill-fated venture that nevertheless foreshadowed an important future direction in naval warfare.

If Davis hoped that taking Beauregard off the field would quiet him down, he was very much mistaken. The general poured out plans and schemes, including a proposal that the governors of the Confederate states meet with the governors of the Union’s Midwestern states—where pro-Confederate (so-called Copperhead) support was strong—and persuade them to make a separate peace. When Davis rejected this out of hand, Beauregard proposed a radical revision of military strategy, which called for shifting a great deal of strength away from Robert E. Lee and the Eastern Theater and putting it in the West, in order to threaten the Union by way of its back door. This grand redistribution of military assets was to be coordinated with action by a fleet of British-built torpedo-rams to be used to recapture New Orleans, thereby threatening the Union from the southwest as well.

Nothing came of any of Beauregard’s grand strategies, which apparently were not even accorded a serious hearing. Instead, he was sent in 1864 to assist Army of Northern Virginia commander Robert E. Lee in the defense of Richmond as it was being menaced by Grant’s Overland Campaign. On May 15, he deftly defeated the inept Major General Benjamin Butler at the Battle of Ware Bottom Church, which was followed by construction of the Howlett Line, a fortified defensive line thrown across the town of Bermuda Hundred, thereby bottling up Butler and his Army of the James, effectively neutralizing it for the remainder of the war.

Beauregard followed his feat at Bermuda Hundred with an extraordinary defense at the so-called Second Battle of Petersburg on June 15 to 18. With no more than 2,200 men initially, he held off an assault by some sixteen thousand Union troops. Had Union general William F. “Baldy” Smith acted aggressively at the beginning, Beauregard would surely have been defeated. But thanks to the combination of Smith’s delay and Beauregard’s bravado, the Confederate commander bought time for the reinforcement of the Petersburg defenses and prevented the Union from scoring a potentially war-winning breakthrough. Beauregard’s stand brought about a ten-month Union siege of the city.

Having defeated Butler and saved Petersburg from immediate invasion, P. G. T. Beauregard believed that Lee and Davis would have no choice but to accept his newest proposal: that he lead an all-out offensive against the North, sweeping Butler aside and wiping out Grant, thereby quite tidily winning the war.

Neither Davis nor Lee believed Beauregard’s scheme was anything more than so much airy talk. Davis did give him a new assignment in October, however, ordering him to turn his divisions over to Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and assume command of the Military Division of the West. The catch was that he would not have direct responsibility for field operations. He was to oversee them, yet to refrain from intervening in them unless there was a crisis. Intended to keep a popular general in the public eye while denying him ultimate command authority, the arrangement was a blatant example of Davis’s mismanagement of the military situation.

When John Bell Hood resigned as commander of the Army of Tennessee (part of the Military Division of the West) in February 1865, Beauregard persuaded Davis to replace him with Joseph E. Johnston. Johnston, in turn, asked Beauregard if he would consent to serve in the field, under his command. We do not know what answer Johnston expected. Certainly those who knew Beauregard throughout the war would not have predicted the response he gave, which was a simple and gracious yes. For the good of the cause, he would step down from departmental command and accept, yet again, the number two post in an army.

It was a noble gesture, but by this time the Confederacy lacked the resources even to slow, let alone stop, either Grant or Sherman, and soon after Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Grant on April 9 at Appomattox, Beauregard and Johnston united with Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge in reporting to President Davis that the cause was lost and surrender was the only remaining reasonable option. General Johnston formally surrendered the Army of Tennessee to Sherman at the Bennett Place, near Durham, North Carolina, on April 26, 1865.

Beauregard in later life. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

P. G. T. Beauregard did not behave as the diehard Old South reactionary he certainly seemed to be at the start of the war. To be sure, he rejoined the Democratic Party, and he protested against the harsh aspects of Radical Republican Reconstruction, but, at the same time, he spoke out in favor of granting full civil rights, including full voting rights, to the emancipated slaves.

The world had been watching him during the war, and he received offers to command the armies of Romania (1866) and Egypt (1869), but he turned these down to become a Southern railway tycoon and consulting engineer. He served profitably as president of the New Orleans, Jackson & Mississippi Railroad from 1865 to 1870 and also of the New Orleans and Carrollton Street Railway from 1866 to 1876. During his tenure with the latter, the old engineer designed a system of cable-drawn streetcars.

He served as adjutant general for the state militia of Louisiana and as manager of the Louisiana Lottery, a corrupt institution he was charged with reforming. This he proved unable to do. In 1888, he was elected commissioner of public works for New Orleans and held this office until his death on February 20, 1893.