RATING:

John Hunt Morgan. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

A self-taught tactical innovator of great courage, John Hunt Morgan brought the hit-and-run cavalry raid to its height in the Civil War and used it as an instrument of what today would be called asymmetric warfare—the effective application of a significantly smaller power against an enemy’s larger force. He went on to develop the long-distance raid as a vehicle of insurgency and as a means of logistical disruption and the dissemination of terror among a civilian population. Morgan was far less successful in developing his raiding tactics for strategic effect, however, and, in the end, his operations had no discernible impact on the outcome of the war in his theater. Worse, his ambitious raid into Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio squandered the most effective light cavalry in the Confederate army, frittering it away piecemeal and without real strategic effect. In the end, Morgan had more import as a proud icon of the “Lost Cause of the Confederacy” than as an active general in the Confederate forces.

Principal Battles

PRE–CIVIL WAR

U.S.-Mexican War, 1846–1848

CIVIL WAR

In our own age, a soldier like John Hunt Morgan would be called a practitioner of asymmetric warfare, an expert in the effective employment of small forces against much larger military formations. In his own day, he was dubbed a cavalry raider by the Confederates who adored him and a common criminal by the Union officials under whose saddles he was a perpetual burr.

Morgan was a remarkable warrior. Without the benefit—or the handicap—of formal military training, he used cavalry as it had never been used before, in a manner that anticipated certain aspects of partisan or insurgent warfare in the mid-twentieth century and beyond. His was a force of deep penetration and disruption, partly logistical in its impact, partly psychological. He was a nineteenth-century insurgent. Had any significant number of other Confederates followed his example, the Civil War would have been very different in its character, a guerrilla affair with few “set” battles.

John Hunt Morgan was born in Huntsville, Alabama, on June 1, 1825, the first of ten (some sources report eight) children of Calvin Morgan and the woman Calvin had brought back to Huntsville from Lexington, Kentucky, Henrietta Hunt, a celebrated beauty. Although John Hunt Morgan’s maternal grandfather, John Wesley Hunt, was a founding father of Lexington and reputedly the first millionaire in Kentucky, Calvin lost his own house in Huntsville in 1831 when the failure of his pharmacy left him unable to pay his property taxes. This brought the Morgans back to Lexington, where John Wesley Hunt employed Calvin Morgan as an overseer on one of his large plantations.

The change from Huntsville to Lexington had a profoundly formative effect on John. From his wealthy grandfather and his associates in the world of the Kentucky plantation, the boy imbibed the quasi-feudal values of the Old South to a far greater degree than if he had known only the world of his pharmacist father. By the age of sixteen, when he enrolled in Lexington’s celebrated Transylvania College, John Hunt Morgan was already a courtly, soft-spoken Southern gentleman, a handsome horseman who exuded both a quiet self-confidence and a powerful sense of entitlement. Indeed, he soon chafed under the discipline of the classroom, whose intellectual demands held no allure for him. His parents as well as his grandfather did not withhold their criticism from the youth, who became increasingly restless and even ungovernable. Responding to a perceived insult from a classmate, young Morgan challenged him to a duel. This resulted in Morgan’s suspension from the college in June 1844 after two years in attendance. He would never return.

Morgan frittered away the next two years until the outbreak of the war with Mexico moved him to enlist as a private in the 1st Kentucky Cavalry. The combination of his horsemanship and family connections quickly earned him a first lieutenant’s commission in the regiment, which he retained when the unit was mustered into the federal service. He reached the front early in 1847, in time to participate in the Battle of Buena Vista (February 22–23, 1847), in which the Kentucky Cavalry performed magnificently.

Buena Vista was the last big battle in northern Mexico and the final battle for Major General Zachary Taylor’s army. Morgan and the other Kentuckians were mustered out of the service on July 8, 1847. Surprisingly, perhaps, Morgan showed no interest in remaining in the U.S. Army. He had enjoyed combat, but the experience seems to have exorcised his restless demons, and when he returned to Kentucky, he used some of his grandfather’s money to purchase a hemp manufactory and subsequently added to this a woolen mill as well as a mercantile concern his grandfather bequeathed to him on his death in 1849. The year before, Morgan, twenty-three, married Rebecca Grantz Bruce, his business partner’s eighteen-year-old sister.

John Hunt Morgan became a Southern capitalist, comfortable, confident, and a surprisingly prudent manager. He dipped deeply into the marketing of slaves, and he also became active in local politics and community affairs. This extended, in 1852, to his sponsorship of a militia artillery battery, but his interest in it soon flagged, and the outfit disbanded by 1854. In the meantime, although Morgan prospered, tragedy struck his wife, Rebecca, who developed a disorder diagnosed as septic thrombophlebitis—an infected blood clot—after delivering a stillborn son in 1853. Her condition worsened, eventually necessitating the amputation of her leg. Increasingly an invalid, she grew totally dependent on the continual ministrations of her husband, something he resented but suffered in silence. What he could not remain silent about was her family’s strident antislavery views, which conflicted with both his own beliefs and his business. Partly in an effort to get away from home whenever possible, Morgan raised a new independent militia unit in 1857, this one a company of cavalry, which he christened the “Lexington Rifles.” To occupy his time and in earnest preparation for what he believed was a coming civil war, Morgan dedicated himself to drilling his men, transforming them into a crack unit.

Although Morgan believed in the rightness of slavery, he was, like most of his fellow Kentuckians, a Union loyalist. He took President-elect Lincoln at his word, that he believed the Constitution protected slavery and that he did not intend to interfere with it, and he wrote to his younger brother Tom that he hoped Kentucky would not secede. “Lincoln,” he wrote, “will make a good President” and is at least entitled to “a fair trial & then if he commits some overt act all the South will be a unit.”

Tom Morgan agreed with his brother on the undesirability of secession; however, in the early summer of 1861, he enlisted in the Kentucky State Guard, which fought for the Confederacy. John Hunt Morgan did not feel that he could leave his wife, but when she died on July 21, 1861, there was nothing to hold him in Lexington any longer. He settled his business affairs and, in September, led his Lexington Rifles to Confederate Tennessee and presented them to the Provisional Army of the Confederate States.

In November 1861, with Kentucky now a battleground, Albert Sidney Johnston ordered Morgan and his Lexington Rifles to Bowling Green. They operated in the rear of Don Carlos Buell’s Federal lines, taking prisoners and disrupting supplies and communications. Hit-and-run tactics were their calling card, and they proved highly effective. From the end of 1861 to the early spring of 1862, the Lexington Rifles conducted one raid after another, sometimes disguised in Union uniforms to disrupt rear echelon operations. Morgan became a popular local figure and earned the admiration of Johnston and other officers.

On April 4, 1862, Morgan was promoted to full colonel and given command of the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, of which the Lexington Rifles formed the nucleus. Days later, he and his new command were committed to something bigger than a hit-and-run raid when they were sent to fight at Shiloh. Quickly finding that the tangled terrain was not suited to cavalry, Morgan ordered his men to dismount, and they fought as infantry. It was a valuable lesson that proved to the commander just how flexible his regiment could be.

After Shiloh, in May, Morgan swept variously throughout Tennessee and Kentucky, perfecting the doctrine and tactics of the hit-and-run cavalry raid. The key elements were attacking isolated elements of big units; avoiding becoming outnumbered; striking with great speed; inflicting maximum damage in minimum time; splitting up to confuse the enemy; and vanishing as quickly as you appeared. With these raids, Morgan earned the sobriquet by which he would become famous: the “Thunderbolt of the Confederacy.”

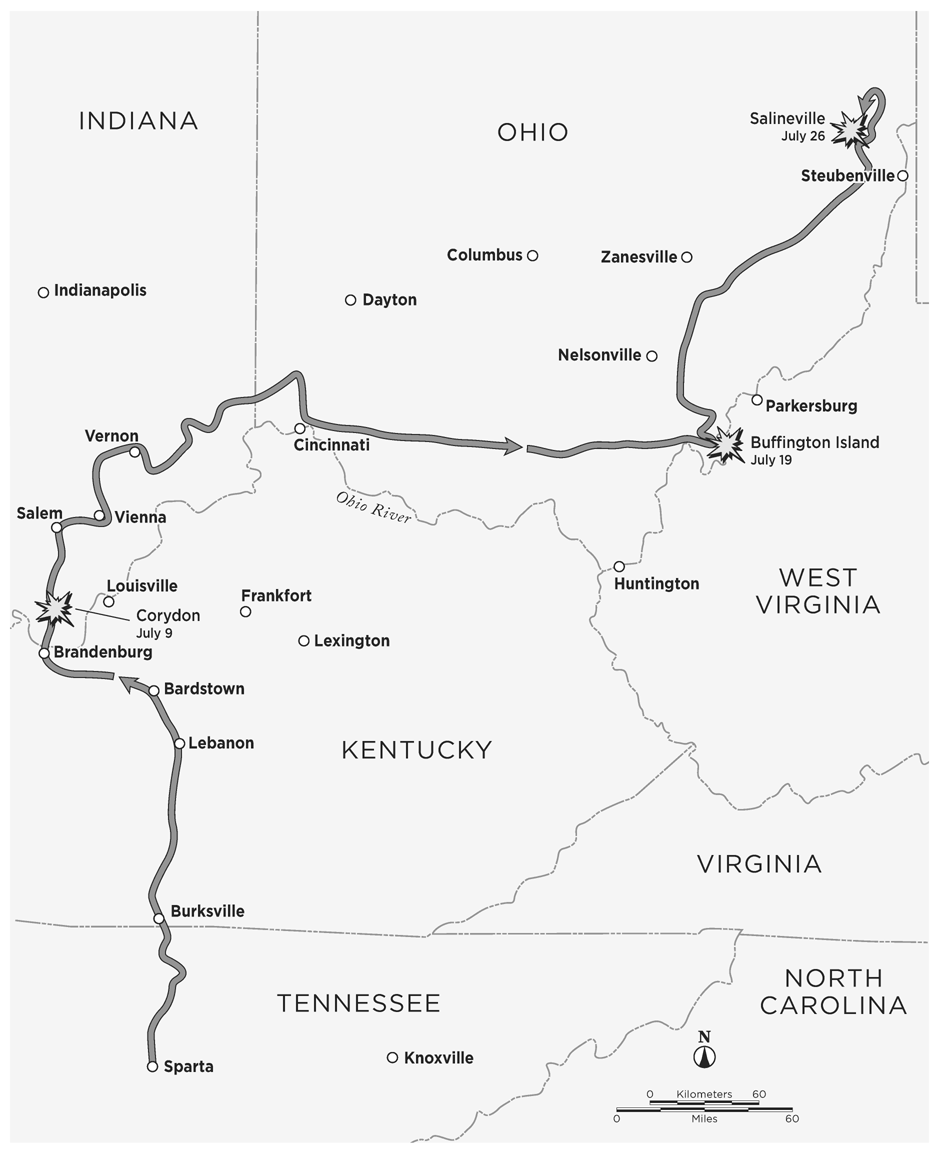

MORGAN’S RAID - JULY 1863

On July 4, 1862, Morgan left Knoxville with nearly nine hundred men for the First Kentucky Raid, which terrorized the region for the next three weeks. Again operating in the rear of Buell’s army, the raiders took some twelve hundred Federal prisoners (who were instantly paroled, because their presence would overburden the raiders), stole hundreds of horses, and appropriated or destroyed large quantities of Union supplies. All of this was bad enough for Buell’s lumbering Army of the Ohio, but it was the effect on military and civilian morale, as well as on the tenuous Union government of this border state, that constituted the heaviest damage.

The effect on Confederate morale was nothing short of miraculous—and, in the end, misleading. Morgan generated excitement in Kentucky, and he also attracted volunteers. He had begun his First Kentucky Raid with nine hundred men. He ended it with 1,200. The success of the raid, the excitement it created, and the growth of Morgan’s command contributed to Braxton Bragg’s perception that Kentucky was ripe for rebellion and that he was the one to “liberate” it by means of a risky invasion. Morgan’s experience had prompted Bragg’s assumption that Kentuckians were eager to rally to the Confederate cause. As it turned out, they were not. Insofar as Morgan’s raids drove Bragg to act rashly, they did at least as much harm as good.

Although Morgan was becoming famous as a raider, he was actually most successful when he coordinated his unique hit-and-run cavalry tactics with the actions of larger forces, as he did during the Stones River Campaign in Tennessee. While the major armies of Braxton Bragg and William S. Rosecrans sparred with one another ahead of the Battle of Stones River (December 31, 1862–January 2, 1863), Morgan led his raiders in a lightning attack against the Thirty-ninth Brigade, XIV Corps of Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland on December 7 at Hartsville, Tennessee. Hitting the Union encampment early in the morning, Morgan’s men wore a mixture of blue uniforms and civilian clothing, which deceived the Union pickets. Surprise was total, and with just 1,400 men, Morgan defeated 2,106, killing 58, wounding 204, and capturing 1,844. Joseph E. Johnston, the Confederate theater commander, hailed this as a “brilliant” victory and recommended Morgan’s immediate promotion to brigadier general, which came through on December 11, just four days after the battle. He felt himself ready to undertake even more ambitious operations.

Spectacular as they were, Morgan’s early raids drew some criticism for having minimal strategic effect. In June 1863, the new brigadier general sought to answer his critics by mounting what he conceived as a genuinely strategic raid. Its object would not only be the usual disruption of Union rear-echelon operations and interdiction of supply and communication lines, but, even more important, it would serve to force Union commanders to divert resources from Vicksburg in Mississippi and from the Mississippi Valley generally, thereby relieving pressure on Braxton Bragg’s beleaguered Army of Tennessee.

This would be no small-unit raid. Morgan led 2,460 cavalrymen—the finest in the Confederate service, which meant the best on the North American continent—out of Sparta, Tennessee, on June 11, 1863. From the outset, however, he departed from the strategic plan he had drawn up with Bragg, who had command authority in the region. Bragg ordered Morgan to limit his activities to Tennessee and Kentucky, so as to provoke the desired Union troop diversions in the region. On his own, however, Morgan decided to extend the raid into Indiana and Ohio for the explicit purpose of terrorizing the North.

Morgan crossed into Kentucky on July 2 and engaged outnumbered elements of the 25th Michigan Infantry at the Battle of Tebbs Bend on July 4. Outgunned though they were, the Union troops deflected the attack and avoided capture (inflicting eighty casualties on Morgan while suffering twenty-nine), but Morgan continued northward, surprising a Union garrison at Lebanon on July 5. In an intense six-hour battle, General Morgan’s brother Tom was killed, but the raiders captured the garrison (unable to accommodate prisoners, Morgan ordered their immediate parole) and burned most of Lebanon’s public buildings.

Grief-stricken by the loss of his brother, Morgan nevertheless pressed on due north to Bardstown, engaging small Federal units along the way. At Bardstown, he took a turn both unexpected and unauthorized. Instead of continuing north to Louisville, he veered northwest to Brandenburg on the Ohio River. Before he crossed the river into Indiana, he split up his command to create confusion, but this dodge succeeded only in getting the detached portion captured near New Pekin, Indiana. Morgan was more successful using another deceptive tactic, tapping into telegraph lines and faking Union messages replete with disinformation and greatly inflated estimates of his numbers. This manipulation of a key Civil War–era technology was typical of Morgan at his most inventive.

Although Morgan’s venture into Indiana was unauthorized, it was not impulsive. He had sent his spy, Captain Thomas Hines, into Indiana the month before to determine if local Copperheads (Confederate sympathizers) would likely rise up in support of a rebellion. Hines reunited with Morgan at Brandenburg on July 8, and although his news was discouraging—there would be no Copperhead uprising—Hines joined the raiders in commandeering a pair of steamers, the John B. McCombs and the Alice Dean, to cross the river into Indiana with the 1,800 men left in Morgan’s command. At their landing place, Mauckport, they were met by a unit of Indiana home guardsmen, which they easily drove off. The fleeing Indianans left behind some valuable artillery, which Morgan appropriated. He put the Alice Dean to the torch and sent the John B. McCombs downriver, charging its skipper to warn away all would-be pursuers. Panic now rippled through Indiana, and its governor, Oliver P. Morton, put out a call for militia volunteers while Major General Ambrose Burnside, commanding the Department of the Ohio, dispatched Union forces as well as militia to interdict Morgan’s routes back to the South.

But this was no hit-and-run raid. Instead of turning back south, Morgan continued north and, on July 9, a mile south of Corydon, he encountered more militia, which he readily outflanked, routing the outnumbered force of perhaps 400 to 450 men. It was after this Battle of Corydon that Morgan’s raiders began taking a toll on civilians, killing a toll taker and a Lutheran farmer-minister and stealing horses and cattle. Popular sentiment, even among Copperheads, began to turn against the raiders.

Morgan swung northeast, sowing terror through the region’s small towns. In a skirmish on July 11, a number of his men were captured. This setback seems only to have hardened Morgan’s attitude, and, riding into Salem, Indiana, on July 12, he set fire to railroad cars, a depot, and railway bridges, looted merchants, and demanded what he called “taxes” from local flour and gristmill operators before setting out east to the Ohio border.

Morgan crossed the Indiana-Ohio line on July 13, along the way wrecking whatever seemed to him of military value and deftly evading the forces Burnside had organized mainly to defend Cincinnati. Burnside, however, studied his maps carefully, and he correctly surmised that Morgan would seek to return to the South via West Virginia. The only convenient means of crossing the Ohio into that recently created state was at Buffington Island, which had a lightly defended Union fort. Burnside dispatched Union troops and gunboats to the scene, while also ordering a militia regiment to hold the fort.

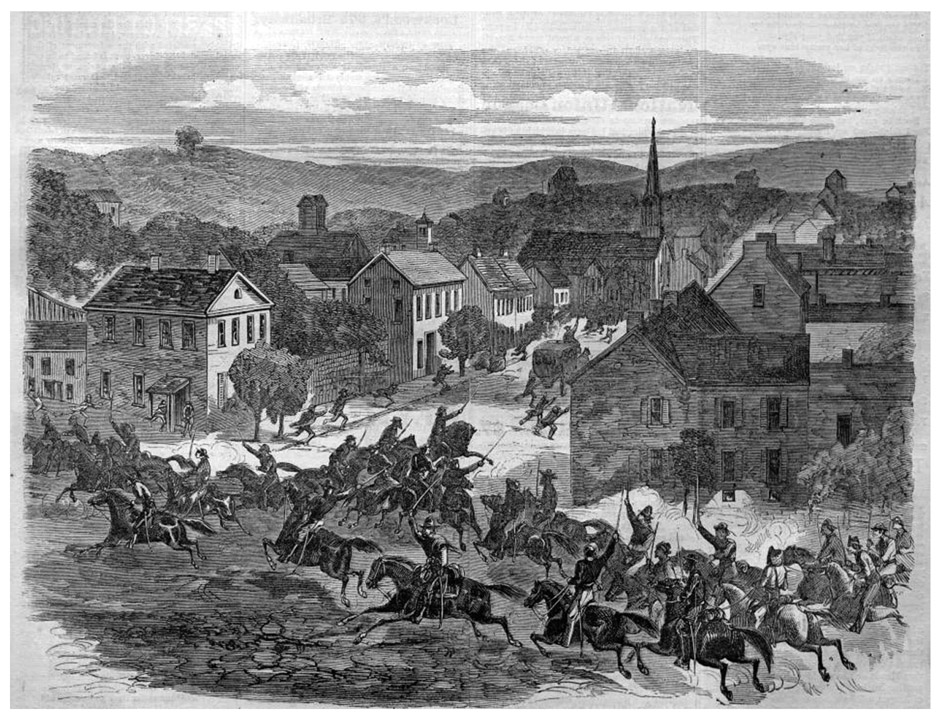

“Morgan’s Raiders Enter Washington, Ohio,” as reported in Harper’s Weekly On August 15, 1863.

HARPER’S ILLUSTRATED WEEKLY

It was a close race. Morgan arrived opposite Buffington Island at dusk on July 18, and while he saw that the fort was garrisoned only by the militia, he decided that it was too hazardous to attack at night. His delay proved fatal. The cavalry and gunboats Burnside had sent arrived on the morning of July 19, and the Battle of Buffington Island that day pitted 14,000 Union troops against just 1,700 raiders, killing 52 of them, wounding 100, and capturing some 750, including another of the Morgan brothers, Richard, and Morgan’s top lieutenant, Colonel Basil W. Duke.

Morgan and the remaining raiders were blocked on the south, so they continued northeast deeper into Ohio. Some three hundred raiders subsequently managed to slip into West Virginia, but Morgan continued to raid in Ohio, losing troopers at each skirmish along the way as he probed for a place to cross the Ohio River. His pursuers never let up, and on July 26, Union cavalry under Brigadier General James M. Shackelford ran to ground Morgan and the four hundred or so men who were still with him at the Battle of Salineville.

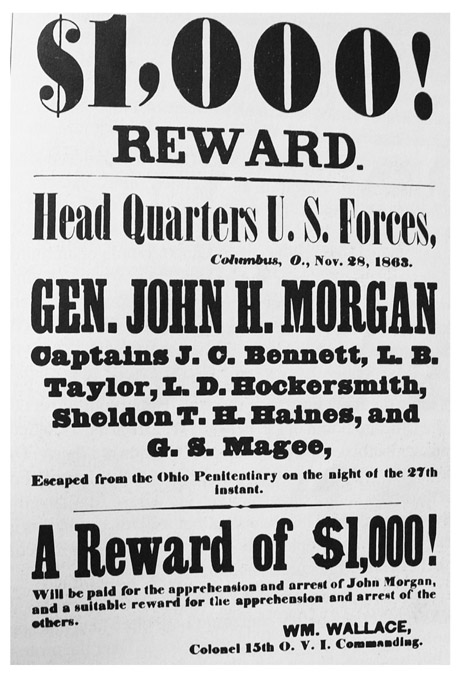

Morgan and his officers were not treated as prisoners of war, but, in a calculated insult, were labeled common criminals and accordingly remanded to the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus. (Most of the enlisted men were shipped off to Camp Douglas, a vast and squalid prisoner-of-war stockade outside of Chicago.) Astoundingly, the penitentiary proved unable to hold them. On November 27, 1863, Morgan and six officers, including the spy Thomas Hines, tunneled out of their cells, into the prison yard, and to the wall, which they climbed to freedom. Two were subsequently recaptured, but Morgan and four others returned to Confederate territory, where they were feted as heroes.

Poster announcing a reward for the capture of John Hunt Morgan, escaped from the Ohio Penitentiary. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

In forty-six days they had ridden over one thousand miles, had taken some six thousand Union soldiers and militiamen prisoner (all were immediately paroled), had destroyed many bridges, and had torn up miles of railroad track. Hundreds of thousands of dollars in military supplies and civilian goods were looted or destroyed. In Ohio, some 2,500 horses were stolen and approximately 4,375 private homes and businesses were ransacked and robbed. Yet while it did draw some thousands of Union troops away from other duties, the raid had negligible strategic impact, especially in the shadow of the great Union victories at Gettysburg (July 3) and Vicksburg (July 4).

For the Confederacy, the net result of Morgan’s Raid was worse than strategic ineffectiveness. In exchange for inflicting a certain amount of terror, looting, and destruction, Morgan frittered away the best light cavalry the Confederacy had. Bragg complained that this cavalry would have been of much greater value to him and his hard-pressed western command in direct battle against the enemy army, and while he did not dare to court-martial or cashier the popular Morgan, he urged General Johnston to assign him, on August 22, 1864, to command the relatively small Trans-Allegheny Department, which encompassed eastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia.

Morgan mounted more raids, but the men he commanded were nothing like his original handpicked elite. The new raids into Kentucky were little more than pillaging sprees, so wildly unmilitary that they prompted a Confederate War Department investigation, which charged Morgan with allowing the equivalent of banditry. Clearly, Bragg and others were setting up the “Confederate Thunderbolt” for removal from command. Before this could happen, however, he was killed.

Around five o’clock in the morning on September 4, 1864, Federal cavalry surprised Morgan as he woke in the appropriated bedroom of an appropriated house in Greeneville, Tennessee. Pulling on his britches and boots, Morgan hid in some bushes near the house. The official Union report of what happened next was that Morgan refused an order to halt and was therefore shot. Morgan’s men, however, told the story very differently. They claimed that the unarmed general came out of his hiding place, hands up, and called out, “Don’t shoot. I surrender.” A Union trooper replied, “Surrender and be God damned—I know you.” With that, he leveled his carbine and shot John Hunt Morgan down, crowing to his fellow troopers that he had “killed the damned horse thief.” Confederate authorities never wavered from their assertion that General Morgan had been murdered for fear that, if captured, he would make good another escape highly embarrassing to Union authorities.

The Union troopers could kill John Hunt Morgan, but they could not snuff out his legend. By the time of his death, however, that legend did less to inspire militarily useful action than it added grist to the mythological mill that would grind out the postwar literary, political, and popular culture movement known as the “Lost Cause of the Confederacy”—the idea that the Southern cause, noble, chivalrous, and ultimately right, had been defeated only by the North’s superior numbers and economic power.

A romantic picture of the raider Morgan, engraved after an 1862 photograph. HARPER’S ILLUSTRATED WEEKLY