RATING:

James Longstreet. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

James Longstreet, widely considered the finest corps commander on either side of the Civil War, may also fairly be judged one of the war’s most profound and perceptive strategic and tactical thinkers. In sharp contrast with the resolutely aggressive and offensively oriented Robert E. Lee, whose chief lieutenant he was, Longstreet advocated what he called “tactical defense,” a policy of enticing the enemy to attack one’s own strongly defended positions. This approach was based largely on Longstreet’s understanding of the nature of the weapons technology of the era, which enabled long arms and cannon to be fired continually and in mass, a circumstance (Longstreet understood) that invariably favored the defender.

The downside of Longstreet’s allegiance to “tactical defense” was inflexibility when it came to accommodating offensively oriented plans and orders with which he disagreed. His response was sometimes passive-aggressive and sometimes more frankly defiant. In either case, the result was damaging to outcomes. For this reason, he must be rated in the upper middle rather than the top rank of the conflict’s commanders.

Principal Battles

PRE–CIVIL WAR

U.S.-Mexican War, 1846–1848

CIVIL WAR

As a boy, he dreamed of martial glory and devoured books about Washington, Napoleon, Caesar, Alexander, all of history’s “great captains,” those credited in the collective human memory with war-winning victory and conquest. As an adult, James Longstreet would begin to live his dream, becoming the senior lieutenant general of the Confederacy and winning acclaim as a master battlefield tactician. Yet the dream was shattered at Gettysburg, and the remainder of Longstreet’s long and mostly successful life was shadowed by accusation and recrimination. The boy who would be conqueror became the favorite scapegoat of those Southerners who reveled in mourning the valiant “Lost Cause.”

James Longstreet was born on January 8, 1821, in the heart of the plantation South, the Edgefield District of South Carolina. On his father’s side, the family traced its American roots to the Dutch New Netherland colony of the mid-seventeenth century. James, his father, had grown up in New Jersey, and his mother, Mary Ann Dent, in Maryland. They were, therefore, Northern immigrants to the Southern way of life.

The senior Longstreet encouraged his son’s early dreams of a military career, and for that reason sent him to Augusta, Georgia, when he was nine, so that he could attend the Richmond County Academy, which offered (Mr. Longstreet believed) the level of academic preparation necessary to get him a place at West Point. In Augusta, the boy lived with his aunt and uncle, a warm and kindly couple with considerable influence in the community. Uncle Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, owner of a plantation called Westover on the edge of the city, was not only a newspaper editor, teacher, and Methodist minister, but he had also served in the state legislature and on the state supreme court. In 1833, James’s father died during a cholera epidemic. His mother and siblings moved to Somerville, Alabama, but young James remained in Augusta with his aunt and uncle.

Although James disdained study and often produced disappointing results at the Richmond County Academy, Augustus flexed his considerable political muscle in 1837 to obtain for him an appointment to West Point. When he discovered that Georgia’s quota of cadets had been filled, he wrote to Mrs. Longstreet, who prevailed on her relative, Reuben Chapman, congressman for Alabama’s First District. It was he who secured the appointment, and Cadet James Longstreet passed through the academy’s gates in June 1838 as a nominee from Alabama.

Athletic and eager to learn the rudiments of tactics, strategy, and the military art, Longstreet turned in no more than a marginal academic performance. He was popular, but his popularity was founded in part on his willingness to get himself into trouble. Close friends included classmates Daniel Harvey Hill, George Pickett, and John Bell Hood—all destined to become prominent Confederate generals—but also such Union luminaries as William S. Rosecrans, John Pope, and George Henry Thomas. Another classmate, Ulysses S. Grant, would become his friend for life and, after the war, a political benefactor. The combination of mediocre academics and a multitude of demerits put him at the bottom of his Class of 1842, number fifty-four out of fifty-six cadets.

Commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Infantry, Longstreet was posted to Jefferson Barracks, at St. Louis, Missouri, from 1842 to 1844. He was delighted when Grant was subsequently posted to the barracks as well, and he introduced his best friend to his fourth cousin, Julia Boggs Dent, whom Grant married in 1848—with Longstreet serving as best man. While stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Longstreet also met his future wife, Maria Louisa (Louise) Garland, daughter of Lieutenant Colonel John Garland, commander of Longstreet’s regiment. They would be married the same year that Grant and Julia wed.

In the fall of 1844, Longstreet left St. Louis for stints in Louisiana and in Florida, which was followed in 1846 by a transfer to the 8th U.S. Infantry on the Texas-Mexico border as the two nations hurtled toward war.

Longstreet began his service in the war with Zachary Taylor’s Northern Army, fighting at Palo Alto (May 8, 1846), Resaca de la Palma (May 9, 1846), and Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846). Casualties were heavy, especially at Resaca de la Palma, and badly depleted units were repeatedly reorganized; thus, after Monterrey, Longstreet was transferred to the Southern Army of Winfield Scott and fought at the Battles of Contreras (August 19–20, 1847) and Churubusco (August 20, 1847), for which he was brevetted to captain. For his gallantry at Molino del Rey (September 8, 1847), he received another brevet promotion, to major.

Longstreet played a prominent role in the Battle of Chapultepec (September 12–13, 1847), when he had the honor of bearing the regimental colors up the steep slope to the castle. As he was approaching the wall surrounding the stronghold, he took a bullet in the thigh and began to fall. As he fell, he handed the colors to his friend and West Point classmate Lieutenant George E. Pickett, who carried them over the wall.

After a prolonged and painful recovery from his wound, Longstreet was briefly posted again at Jefferson Barracks, and then, in May 1849, traveled with his wife and newborn son to San Antonio, Texas, where he served as 8th Regiment adjutant. Over the next twelve years, he and his family moved from one frontier post to another, mostly in Texas, including Fort Martin Scott near Fredericksburg and Fort Bliss in El Paso. His duties were uneventful, even when he led scouting missions along a frontier that was often torn by white-Indian violence.

In July 1858, Longstreet was promoted to the regular army rank of major and was assigned as the 8th Infantry paymaster. During this period he may have been active in a scheme to annex the Mexican state of Chihuahua and bring it into the Union as a slave state. The evidence for this is not definitive, however. There can be no doubt that he supported slavery and shared his Uncle Augustus’s belief in the doctrine of states’ rights, but he was never an enthusiastic advocate of secession, which he thought impractical, even though he believed that it was within a state’s rights to leave the Union. Unlike many others who would resign their U.S. Army commissions to fight for the South, Longstreet did not closely identify with his birth state, South Carolina, nor with Georgia, the state in which he had come of age. It was only after the fall of Fort Sumter in April 1861 that he decided to cast his lot with the Confederacy, and he did so by resigning his commission on May 9, 1861, and offering his military services to Alabama, mainly because that state had sent him to West Point and his mother lived there.

Almost immediately after presenting himself to Governor Andrew Moore of Alabama, Longstreet was commissioned a lieutenant colonel, not, however, in the state forces, but in the Provisional Army of the Confederate States. He was sent to Richmond to meet with President Jefferson Davis, who, on June 22, 1861, told him that, as of June 17, he had been commissioned a brigadier general. On June 25, the day on which he formally accepted the commission, he was ordered to report to Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard at Manassas, Virginia. That officer assigned him command of a brigade consisting of the 1st, 11th, and 17th Virginia Infantry regiments.

Anticipating imminent combat, Longstreet subjected his brigade to an accelerated regimen of drill. Contact with the enemy came on July 18, 1861, at Blackburn’s Ford on Bull Run Creek in Prince William and Fairfax Counties. Longstreet’s brigade easily repulsed a Union reconnaissance force in this prelude to the major battle of July 21.

Although Longstreet and his brigade had had the honor of first contact, they were not heavily committed in the First Battle of Bull Run proper. This was not for lack of trying. Longstreet was among those who pleaded with Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston to pursue the beaten Union army, to dog it all the way to Washington. When his entreaties fell on deaf ears, he exclaimed to his aide Moxley Sorrel, “Retreat! Hell, the Federal army has broken to pieces,” then dissolved into a wordless fury over the great opportunity that was being squandered.

Throughout his Civil War career, Longstreet would find himself drawing criticism as overly cautious, deliberate, and methodical. He would emerge as a master of defensive rather than offensive warfare. Yet he certainly recognized an opportunity to expand on a victory when he saw it, and at Manassas he burned with futile desperation to make something more of what had been accomplished in the Confederate army’s first major clash with the Union—on Washington’s back doorstep, no less.

Although Longstreet, like others subordinate to Beauregard and Johnston at Bull Run, was frustrated by the failure to pursue Irvin McDowell’s Union troops, his performance before and during the First Battle of Bull Run went neither unnoticed nor unrewarded. On October 7, Longstreet was promoted to major general and was assigned command of a division of Johnston’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Longstreet was known to his family and close friends by the nickname Pete (it had come about through his father’s admiration of his son’s steadfast bearing, which he thought resembled Peter, the “rock” on whom Jesus built his church). Before the Civil War was over, he would often be known as “Gloomy Pete,” but as the army went into winter quarters in the fall of 1861, he was nothing if not jovial, and he was well known to relieve the tedium of camp routine with comradely conversation, convivial drinking, and friendly rounds of card playing. All of this came to a terrible end in January 1862 when an epidemic of scarlet fever swept through Richmond, killing the Longstreets’ year-old daughter and their four- and six-year-old sons within the space of a week. Garland, his thirteen-year-old, barely recovered from the disease. From this point forward, Longstreet was a changed man, subdued in manner and increasingly devout in his practice of the Episcopal faith.

He clearly lacked much of his characteristic energy and acuteness of mind in resisting McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign during the spring of 1862. He was effective in the defensive role of rear-guard commander at Yorktown (May 4, 1862) and Williamsburg (May 5, 1862), doggedly striking at McClellan’s Army of the Potomac and bogging it down as it advanced on Richmond. But when he was called on to conduct the principal attack at the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, he seemed to get everything wrong. Badly misunderstanding General Johnston’s verbal orders, he ended up sending his men the wrong way down the wrong road. They ran into other Confederate units, causing confusion and delay, which blunted what Johnston had intended as an overpowering counterattack against McClellan.

After the battle, Longstreet revealed an unattractive side of himself as a commander. Refusing to accept blame for errors that were clearly his fault, he wrote an after-action report that shamelessly scapegoated Major General Benjamin Huger.

As far as Longstreet was concerned, the only good to come out of the Battle of Seven Pines was the replacement of the wounded Joseph E. Johnston as Army of Northern Virginia commander with Robert E. Lee. The men trusted each other completely, and Lee gave Longstreet operational command of fifteen brigades, almost half of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Having fumbled at Seven Pines, Longstreet was masterful in the Seven Days Battles as he relentlessly pushed McClellan’s Army of the Potomac back down the Virginia Peninsula, forcing him farther and farther from Richmond. At the Battle of Gaines’s Mill (June 27, 1862), the largest of the Seven Days battles, Longstreet was especially aggressive. Indeed, throughout all the battles, he was the standout among Lee’s lieutenants, notably outperforming Stonewall Jackson.

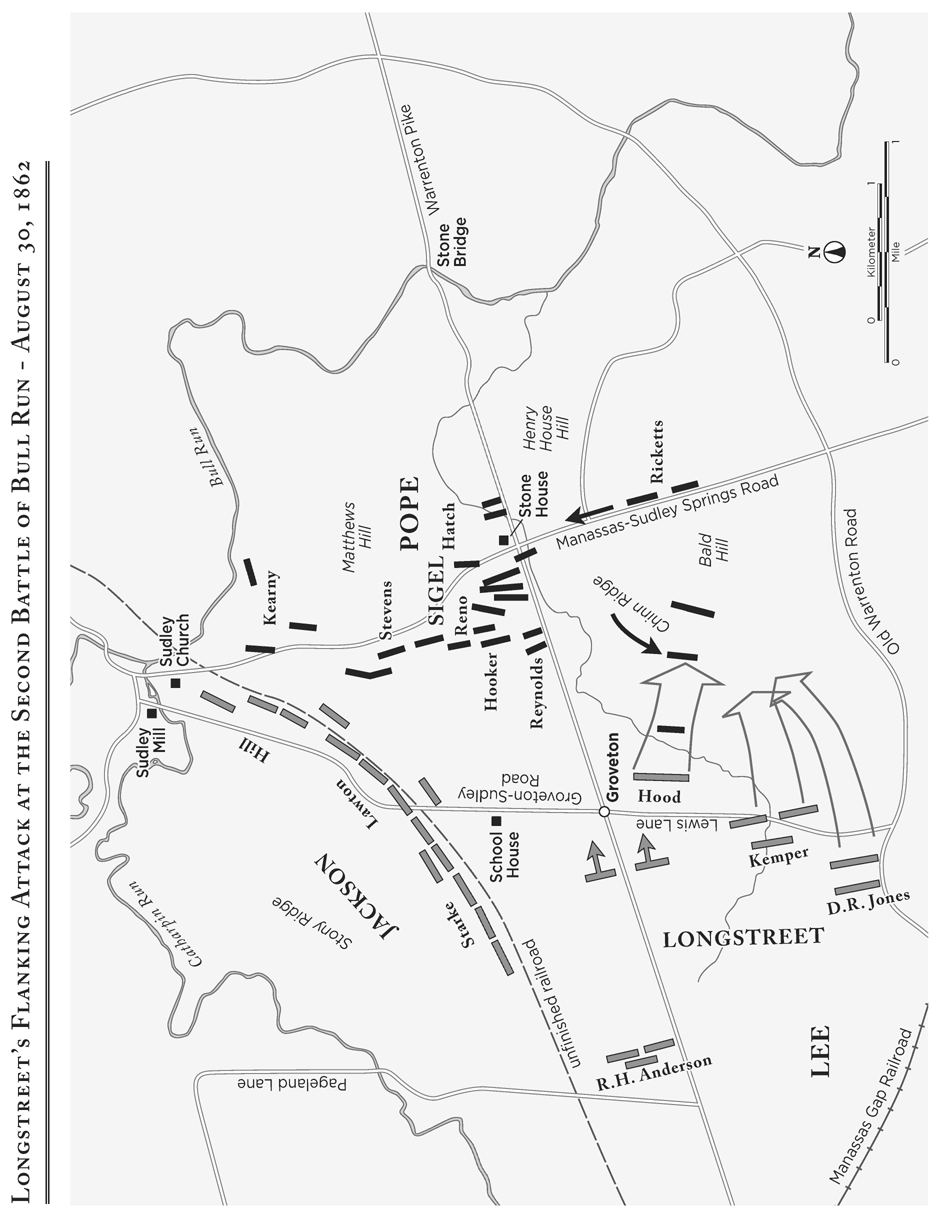

After the failure of McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign, Lee turned his attention toward John Pope’s new army, the Army of Virginia, in what he hoped would be a successful bid to defeat it in detail before Pope could be reinforced by McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. As he prepared to do battle with Pope at Manassas, site of the First Battle of Bull Run, Lee’s audacious strategy was to divide his army in the face of the enemy, assigning Stonewall Jackson to command its left wing and Longstreet its right wing.

Jackson made a broadly arcing advance that sent his wing against the rear of Pope’s Army of Virginia. Then, uncharacteristically, he changed from offensive to defensive mode and took up a position that virtually demanded an attack against him. Pope obliged on August 28 and 29. Confident that he was destroying the Army of Northern Virginia, the Union general was oblivious to the maneuvers of Longstreet’s right wing, which, on August 29, pounded into him.

Among military historians, Longstreet’s admirers applaud his ability to carry out a stunning surprise flanking attack with an entire corps. His critics, however, fault his habitual caution and deliberation. They argue that he should not have allowed Jackson to absorb punishment for two full days before making a decisive move. Indeed, Longstreet’s early postwar critics—those who heaped blame upon him for Lee’s defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg—point to what they call his “reluctance” to attack at Second Bull Run as a prelude to his similar hesitation at Gettysburg.

Even if we grant the criticism some validity, it is hard to overlook the major victory Longstreet brought Lee. Exploiting Pope’s belief that Jackson was in retreat, Longstreet mustered twenty-five thousand men against the Union flank. Even conceding Longstreet’s slow initial approach, the actual attack, once launched, was a masterpiece of field tactics. No commander in the Civil War handled so many men so effectively in achieving a single objective.

Longstreet excelled at defensive strategy, which made him (sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse) the perfect foil to Lee, who adopted a strategy of offense in the belief that the Confederacy could not afford to risk the slow death of attrition a defensive policy might bring. Lee’s invasion of Maryland in September 1862 was, of course, offensive in nature, but he ended up having to take a defensive stance at South Mountain (September 14) and at the Battle of Antietam (September 17).

At South Mountain, Longstreet’s defensive tactics delayed the Union forces effectively as Lee prepared a strong position at Antietam. During that battle, Longstreet’s corps was outnumbered by Union units two to one but nevertheless held the line. He made an ally of the terrain, which effectively evened the odds. Those who ascribe Longstreet’s embrace of tactical defense to a deficiency of bold aggressiveness do him a disservice. Longstreet believed that the massed firepower, both from shoulder weapons and artillery, available to both sides in the Civil War naturally favored those who occupied a strong defensive position. The greater power of the available weapons was defensive—repulsing attacks—not offensive, and Longstreet’s understanding of this put him ahead of his time.

Lee greatly appreciated Longstreet’s performance at Antietam, and, on October 9, pursuant to his recommendation, he was promoted to lieutenant general—the Confederate army’s senior general officer of that rank. The following month, Longstreet was formally assigned command of the Army of Northern Virginia’s I Corps, a force of some forty-one thousand men.

When, after bloody Antietam, Lee withdrew back to Virginia from Maryland and George B. McClellan declined to pursue his retreat, Abraham Lincoln relieved McClellan as commanding general of the Army of the Potomac and replaced him with Ambrose Burnside. Reluctant to accept the command, Burnside was nevertheless eager to prove himself and decided on an immediate advance to Richmond via Fredericksburg.

As Lee’s I Corps commander, Longstreet took the lead in setting up the defense of Fredericksburg. This he did masterfully, creating elaborate defensive works and taking special advantage of Marye’s Heights behind the town. At the foot of this high ground was a long stone wall, behind which Longstreet deployed troops and artillery with very deadly results. Longstreet approached the deployment of all his artillery with exquisite deliberation, ensuring that the field any Union advance would have to traverse would be thoroughly swept by deadly fire.

The battle, when it came, was one of the deadliest and most lopsided of the war. Of some 114,000 engaged, Burnside lost 12,653 killed, wounded, captured, or missing. Lee suffered 5,377 casualties out of some 72,500 engaged. The disparity in casualties was thanks to Longstreet, against whose superbly defended positions Burnside tragically hurled wave after wave.

From April 11 to May 4, 1863, Longstreet’s corps was engaged in operations along the Virginia seaboard, which culminated in the Battle of Suffolk (also known as the Battle of Fort Huger), intended to retake Fort Huger from Union forces. Repossession of this fort would return control of the Nansemond River to the Confederacy and remove the threat of Union seaborne operations against the Army of Northern Virginia. On April 29, however, General Lee ordered Longstreet to break off the engagement so that he could participate in what would become the Battle of Chancellorsville. By the time Longstreet arrived, however, the battle was over and won.

Stereopticon view of the stone wall at Marye’s Heights, Fredericksburg, behind which Longstreet placed riflemen and artillery to deadly effect. NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY DIGITAL LIBRARY

By any measure, Lee had achieved a brilliant victory at Chancellorsville, though at a high cost, and Longstreet’s critics, both in 1863 and today, fault him for having failed to return from Suffolk more expeditiously. They point to this as evidence of his unwillingness to give Lee his full cooperation and suggest that this foreshadowed his lapses at Gettysburg.

The Battle of Chancellorsville brought both an important victory for Lee—which he hoped to expand into a turning point of the war—and a terrible loss: the death of Stonewall Jackson. Without Jackson, Longstreet was now unquestionably Lee’s top lieutenant, and the two debated what to do next.

Longstreet wanted Lee to detach his corps from the Army of Northern Virginia and let him lead it to Tennessee to reinforce Braxton Bragg against William Rosecrans, defeating him and thereby compelling Grant to divert forces from his Vicksburg siege. Lee rejected this essentially defensive strategy and insisted that the Army of Northern Virginia remain concentrated in the east for a major offensive, an invasion of the Union via Pennsylvania.

Longstreet was not happy, but he offered no protest. His only request was that the invasion, by definition an offensive action, should rely on defensive tactics, which he defined as tactics intended to “force the enemy to attack us, in such good position as we might find in our own country.” This, Longstreet argued, “might assure us of a grand triumph.” According to Longstreet’s postwar memoirs, Lee “readily assented” to defensive tactics as “an important and material adjunct to his general plan.” Nothing in the records Lee left, however, corroborates such an assent, and in 1868 Lee directly disavowed having ever made Longstreet “any such promise.” On the other hand, immediately after the Battle of Gettysburg, Lee reported that he had not intended to “fight a general battle at such a distance from our base, unless attacked by the enemy,” which suggests that he intended to pursue the policy Longstreet proposed. If there was an understanding between Lee and Longstreet concerning tactical defense, then Longstreet’s conduct at Gettysburg must be considered beyond reproach. If there was not such an understanding, then Longstreet’s critics gain ground for their assertion that his failure to embrace the aggressive spirit of the battle contributed to the Confederate defeat.

After Chancellorsville, Lee had reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia into three corps, assigning Richard S. Ewell command of II Corps and A. P. Hill command of a newly created III Corps. The four divisions of Longstreet’s original I Corps were reduced to three, commanded by Lafayette McLaws, George Pickett, and John Bell Hood. Leading I Corps, Longstreet trailed II Corps through the Shenandoah Valley. He arrived at Gettysburg too late on July 1 to participate in the first day of battle; however, he accompanied Lee in surveying the situation that had been created on that first day. With his eye for defensive positions, Longstreet judged that the high ground onto which the Union had been driven east and south of Gettysburg gave them a formidable position. Longstreet counseled Lee to avoid a direct assault on it and instead march around the left flank of the Union position to set up a defensive line between the Army of the Potomac and Washington, D.C. This, Longstreet argued, would lure the Union army down from its formidable heights to engage a force that would be perceived as a direct threat against Washington.

Lee protested that this would effectively put him in the position of withdrawing from a fight that had gone so well the first day. He believed that such a “retreat” would be demoralizing, and he insisted on immediately attacking the Union high-ground positions. He believed that the Army of the Potomac was depleted and exhausted by the battering of the first day and that it was ready to break.

Longstreet seems to have been incapable of accepting Lee’s order, and Lee, in turn, seems to have been unable to elicit from Longstreet full, unquestioning, and cheerful obedience. Repeatedly, Longstreet reiterated his case for a flanking movement. Repeatedly, Lee rejected it and on July 2 ordered direct coordinated assaults on the left and right flanks of the Union army. Longstreet stalled in the execution, perhaps hoping that Lee would change his mind. When he finally—and belatedly—commenced the ordered attack, he suddenly, even perversely, insisted on following Lee’s orders to the letter. He rejected John Bell Hood’s very sound suggestion that his division be allowed to attack from the rear, and instead led a blunt frontal assault, which, since his delay had given the Union forces more time to prepare defenses, was doomed to fail.

At the end of day two, the Union was still in possession of the high ground, and on day three, July 3, Lee ordered Longstreet to mount the massive assault against the center of the Union line that history remembers as Pickett’s Charge. Longstreet replied flatly to Lee that he did not want to make the attack. To his subordinate commanders Longstreet remarked, “I do not see how it can succeed.” To him it looked as if the Union troops were in a position precisely analogous to what he had occupied at Fredericksburg, and he had no desire to play the part of Ambrose Burnside. “I have been a soldier all my life,” he pleaded with Lee. “There are no fifteen thousand men in the world that can go across that ground.” But Lee was adamant. Instead of disputing the issue, he simply gestured toward the Union line. “There,” he told Longstreet, “is the enemy, and there I mean to attack him.”

Longstreet was so overcome that when General Pickett asked him for the order—“Shall I lead my division forward, sir?”—according to his own recollection, he could not say a word but “only indicated it by an affirmative bow.” Before it was over, Pickett’s Charge would cost the Army of Northern Virginia some 6,555 men killed, wounded, or captured.

After the catastrophe of Pickett’s Charge and the loss at Gettysburg, Longstreet once again sought transfer to the Western Theater and out from under the shadow of Robert E. Lee. On September 5, Jefferson Davis finally ordered Longstreet to lead the I Corps divisions of McLaws and Hood, together with one brigade from Pickett’s division and an artillery battalion under Porter Alexander, 775 miles to link up with Braxton Bragg in Georgia. No fewer than sixteen railroad transfers were required, and the entire operation consumed three weeks, with Longstreet and the advance elements of I Corps arriving on September 17, 1863, and the bulk of the corps following just in time for the Battle of Chickamauga, which was under way.

Bragg assigned Longstreet command of the left wing of his army and gave the right to Leonidas Polk. On September 20, the second day of the battle, Longstreet massed an attack against a narrow front, which exploited a gap that Rosecrans, confused by battle and the tangled terrain, inadvertently opened up in his line. Longstreet sent the entire Union right in a panicked retreat. Major General George H. Thomas was able to rally some of the retreating elements and form them into a defensive line on Snodgrass Hill. Lacking support from Polk’s right wing, Longstreet beat against Thomas—the “Rock of Chickamauga”—in vain, and with nightfall, Thomas was able to withdraw in good order, thereby preventing a total rout. Had Bragg possessed a greater grip on the overall situation, he would have ordered Polk to reinforce Longstreet, and the Confederate victory, impressive though it was (thanks in large measure to Longstreet), would have been devastating.

Keenly aware of Bragg’s inadequacies, Longstreet agitated for his removal and pleaded his case before Jefferson Davis during a field visit. Davis, personally loyal to Bragg since the two had fought together as comrades during the U.S.-Mexican War, sided with Bragg, who punished Longstreet by reducing the number of troops under his command.

Longstreet struggled against domination by someone he considered a losing general. While Bragg laid siege against the Army of the Cumberland, which had withdrawn from Chickamauga and holed up in Chattanooga, Longstreet proposed a more innovative and active plan to foil Grant’s attempt to break the siege—by gaining control of the rail network and by threatening the Union reinforcements that were arriving to augment the siege. Although Davis approved of Longstreet’s plan, Bragg rejected it—and, once again, Davis backed him. Bragg sent Longstreet and his corps east to check an advance by Ambrose Burnside and occupy Knoxville. He moved so slowly, however, that the city fell before he reached it.

When Bragg’s siege of Chattanooga finally collapsed on November 25, 1863, Longstreet was initially ordered back west to join the Army of Tennessee in its withdrawal through northern Georgia. Instead, he continued on his way eastward, at times pursued by Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, before he linked up with the Army of Northern Virginia in the spring of 1864.

Despite their differences at Gettysburg, Lee was overjoyed to have his “Old War Horse” back with him. At the Battle of the Wilderness, Longstreet immediately demonstrated his worth by pounding into the Army of the Potomac’s II Corps along the Orange Plank Road, taking a terrible toll and almost sending it from the field. The II Corps commander, Winfield Scott Hancock, remarked to Longstreet after the war that he, Longstreet, had “rolled [him] up like a wet blanket.”

When Longstreet was wounded by friendly fire—shot through his shoulder, the round destroying the nerves to his right arm (rendering it useless for much of the rest of his life), then grazing his throat—his attack flagged, giving the Union commanders the time they needed to reform, thereby blunting the Confederate victory. As for Longstreet, his injuries kept him out of the war throughout the remainder of the spring and summer of 1864.

Longstreet rejoined the Army of Northern Virginia in October, as the Siege of Petersburg dragged on. His role was primarily to command the Richmond defenses until the Appomattox Campaign, in which he accompanied Lee as I Corps commander and (after the death of A. P. Hill on April 2) as III Corps commander as well. When Lee discussed surrender with him, Longstreet, who never forgot his friendship with Grant, assured him that the Union general-in-chief would negotiate fairly—though, at the last minute, as he rode with Lee to the McLean House surrender conference at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, Longstreet declared, “General, if he does not give us good terms, come back and let us fight it out.”

Longstreet was intensely active after the war. Settling his family in New Orleans, he became a partner in a cotton brokerage as well as president of the Great Southern and Western Fire, Marine and Accident Insurance Company. Determined to return his life to some degree of normality, he applied to President Andrew Johnson for a pardon, but even though Grant endorsed the application, Johnson turned him down. Congress overrode the president in 1868, restoring Longstreet to the full rights of citizenship.

A Mathew Brady photograph of Longstreet after the war.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Far more controversially, Longstreet joined the Republican Party, supported Reconstruction, and campaigned for Grant for president in 1868. His grateful friend rewarded him with an appointment as surveyor of customs in New Orleans, and the Republican governor of Louisiana named him adjutant general of the state militia. Later, Longstreet also held command of the state police within New Orleans. Many fellow Southerners considered him a traitor to the Lost Cause, and in 1875, fearing for their safety, the Longstreets moved from New Orleans to Gainesville, Georgia. President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in 1880, and under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, he served as U.S. commissioner of railroads from 1897 to 1904.

Longstreet survived a fire on April 9, 1889, that destroyed his Gainesville house and, with it, his trove of Civil War documents and souvenirs. His wife, Louise Longstreet, never recovered from the trauma of the fire and died before the year was out. Eight years later, in 1897, seventy-six-year-old Longstreet married thirty-four-year-old Helen Dortch, having published the year before From Manassas to Appomattox, his wartime memoir, much of which was taken up with a defense of his war record. At the start of the twentieth century, Longstreet’s health went into steep decline, and he died on January 2, 1904, of pneumonia and the complications of cancer.