RATING:

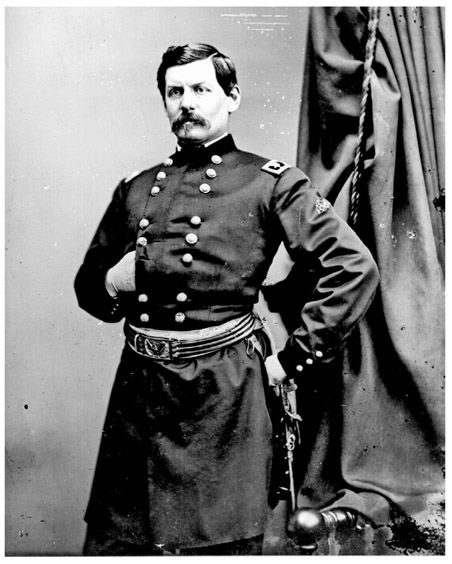

Mathew Brady portrait of George B. McClellan. Dubbed the “Young Napoleon” by a hopeful Northern press, McClellan’s hand in blouse may have been intended to emphasize the comparison; however, it was also a conventional pose in military portraits of the period.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION

Extraordinarily intelligent, number two in his West Point class, universally praised as a brilliant organizer, beloved by his troops, and impressive to the public, George B. McClellan was nevertheless unsuited to large-unit combat command. Personally courageous, he was nevertheless chronically and pathologically inclined to magnify the challenges and obstacles he faced, to believe that those above him wished to see him fail, and, most of all, to wildly overestimate the strength of the enemy. These psychological defects prevented him from committing his troops to battle in a timely manner, which repeatedly resulted in tragically missed opportunities for decisive victories that would likely have shortened if not ended the Civil War before the close of its second year. A talented, earnest, humane officer, McClellan, evaluated in terms of the results he produced and did not produce, was the single most notable failure among the Union’s high command.

Principal Battles

PRE–CIVIL WAR

U.S.-Mexican War, 1846–1848

CIVIL WAR

After the fall of Fort Sumter on April 13, 1861, the people of the North rallied behind such newspaper titans as New York Daily Tribune publisher Horace Greeley in demanding a single great stroke that would avenge the surrender and smash the Confederacy. Old Fuss and Feathers—some were now deriding him even more stridently as “Old Fuss and Feeble”—General Winfield Scott dared to push back against the clamor, arguing that the army was hardly big enough or fit enough to strike a decisive blow and warning that the war would be longer and bloodier than anyone imagined. No one wanted to hear this, and so Brigadier General Irvin McDowell was called on to do what Scott said could not be done.

McDowell was not an entirely unreasonable nominee for the job. Educated in France and at West Point (he graduated in the Class of 1836 alongside Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, whom he was about to face in battle), McDowell was better trained than most U.S. Army officers and had seen combat in the U.S.-Mexican War, though not as a commander of troops in battle. Nevertheless, his climb up the officer ranks, while not totally undeserved, had been due at least as much to his bosom friendship with Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln’s powerful secretary of the treasury, as it was to any demonstration of actual military prowess. When he took charge of what the Union was calling its Army of Northeastern Virginia, McDowell was savvy enough to see that he had been given command of summer soldiers, green men and callow boys who had enlisted as if for a lark. In his private moments, he must have agreed with Scott: They weren’t ready. But he could not stand up to the pressure of the politicians, who in turn could not resist the crush of their constituents, who called for a single bloody blow that would teach the rebels a lesson and finish the rebellion once and for all. What is more, as most Northerners saw it, this really wasn’t asking for much.

McDowell the studious West Pointer drew up a brightly burnished plan of attack against the Confederate forces massed in northern Virginia, a stone’s throw from Washington, at Manassas, along the Bull Run. It looked very good on paper but was burdened by classroom complexities far beyond the ability of his untutored troops and their scarcely better-prepared commanders to execute in the field. Still, by the third week in July 1861, McDowell had assembled at Alexandria, Virginia, the largest field army ever to muster on the North American continent to that time, thirty-five thousand men in blue. With numbers like these, how could they fail?

They could. They did. Bull Run ended in a humiliating Union rout on July 21, 1861.

McDowell’s men had marched to battle at the leisurely pace that suited a soft summer day, many pausing to pick blackberries along the road, which was lined with fashionable Washingtonians, who had brought picnic lunches to enjoy while taking in the show that was about to begin. Now, the battle ended, the survivors—tired, frightened, demoralized troops—elbowed past the picnickers, who dropped baskets and jugs as they joined their defeated army in flight back to a capital that suddenly seemed under siege.

On July 22, the day after Bull Run, news came of two victories in western Virginia, at Philippi and Rich Mountain, won by a young, handsome Union general named George Brinton McClellan. Skirmishes rather than full-out battles, these wins paled in comparison to the catastrophe in northern Virginia—McClellan had inflicted perhaps ten casualties on the Confederates at Philippi and captured some five hundred Confederates at Rich Mountain, while the Confederates had killed, wounded, or captured nearly three thousand Union troops at Bull Run—but they were enough to prompt his urgent and hopeful summons to the capital. A special train was even dispatched to carry him. At Wheeling, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia, as well as all the stops in between, the train was met by the shrill cheers of fevered throngs. Like a starving multitude at the sight of sustenance, a crowd hungry for the comforting news of victory mobbed him at the Washington station on July 26. Troops and Washington cops extricated him, then bundled him off to the White House. There President Abraham Lincoln took his hand and, without the delay of even the briefest ceremony, informed him that he was now commander of the Military Division of the Potomac. At the moment, this gave him responsibility chiefly for the defense of Washington, but McClellan understood that he was to use the division as the nucleus around which to build the major force of the Union army.

To his wife, Ellen Marcy McClellan, the new commander wrote, “I almost think that were I to win some small success now I could become Dictator or anything else that might please me.” He was probably right. But what he wrote also revealed the sum of all that, in the end, made him unfit to command what would become the Army of the Potomac, the largest military formation ever raised on the continent to that time. For if “some small success” was all that was needed to elevate him to dictator, it was far short of what was needed to bring a quick and triumphant end to the Civil War. Reveling in the waves of adulation sweeping over him, McClellan nevertheless tragically underestimated the magnitude of his mission.

But who could blame him? Born on December 3, 1826, into one of the leading families of Philadelphia, the son of a prominent physician, a pampered George McClellan was given a superb education at the preparatory school of the University of Pennsylvania and then, when he was only thirteen, possessed of an intellect just short of outright genius, was enrolled in the university itself. After two years of classes there, in which he was a standout, the fifteen-year-old McClellan was nominated to West Point, the realization of a dream to which he had first given voice at age ten. So impressed was the academy’s board that it waived the minimum age requirement and admitted the lad.

The most promising West Point cadets were tapped for commissions in the Corps of Engineers, and McClellan, who graduated in 1846, second out of a class of fifty-eight, which included future Confederates Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson (seventeenth) and George Pickett (dead last), was so assigned. As is not always true in the case of overachievers, McClellan’s classmates adored the young man. As one of them, William Gardner, later remarked, “We predicted real military fame for him.”

Certainly the gods of martial destiny smiled on Second Lieutenant McClellan and the other graduates of 1846, who found that they had emerged into the biggest war the U.S. Army had fought since 1812, the war with Mexico, which prompted a two-fold increase in the size of the army and opportunities for glory to everyone smart and bold enough to seize them. If McClellan assumed he would be marching from the West Point parade ground directly to Mexico, he was mistaken, however. His first assignment was local, as an aide to an engineer officer, tasked with helping him to train troops. Four long months would pass before he shipped out for Brazos de Santiago, where he served in the Southern Army under Winfield Scott. As an engineer, he was put to work drawing maps, a critically important function in Scott’s fast- and far-moving army but one that kept him out of much of the hottest action, the kind of combat that made a young officer’s military reputation and put him on the high road to rapid promotion. He did at last find himself in the midst of combat at the Battle of Contreras (August 19–20, 1847) on the outskirts of Mexico City. McClellan had two horses shot from under him by Mexican pickets, then was blown off his feet by Mexican artillery fire after he had taken over command of a howitzer when the battery officer fell mortally wounded. Brigadier General Persifer F. Smith, his commanding officer, singled him out in his after-action report, remarking that “nothing seemed . . . too bold to be undertaken, or too difficult to be executed.” He was brevetted to first lieutenant for “gallant and meritorious conduct,” and distinguished himself again, at the Battles of Molino del Rey (September 8, 1847) and Chapultepec (September 12–13, 1847), for which he was brevetted to captain.

After the burst of strenuous glory that was the U.S.-Mexican War, many of the newly minted West Point officers were cast down by the dreary dearth of opportunity that followed in the peacetime army. Unable to advance in their military careers, the likes of William Tecumseh Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant resigned their commissions early in the 1850s. Captain McClellan, however, managed to find opportunity. He taught engineering at West Point from 1848 to 1851, then supervised the construction of Fort Delaware near Delaware City before transferring from the Corps of Engineers to the cavalry and joining Major Randolph Marcy in his Red River Expedition of 1852, an effort to discover the source of that strategic western waterway. Two years later, twenty-seven-year-old McClellan met Marcy’s daughter, Ellen Mary Marcy, an eighteen-year-old beauty with whom he fell instantly in love. “I have not seen a very great deal of the little lady,” he wrote to her mother, “still that little has been sufficient to make me determined to win her if I can.” Greatly impressed with McClellan, Major and Mrs. Marcy did their best to prevail on Ellen, but neither they nor the captain himself could move the girl. She was in love with Lieutenant Ambrose Powell Hill—a dashing young officer who would go on to be a general in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

It must have seemed hopeless, but McClellan was undeterred. He believed that, in time, Ellen’s heart would open to him. This attitude was typical of a man who, increasingly, was coming to believe that God had chosen him for great things and that he had only to wait for his destiny to unfold. As if to confirm this, in April 1855, the United States secretary of war, Jefferson Davis, himself a hero of the war with Mexico—and destined to become the first and last president of the Confederate States of America—quietly summoned Captain McClellan to his office in Washington. There McClellan was joined by Richard Delafield, an engineer and former superintendent of West Point, and Alfred Mordecai, an ordnance specialist. Davis told the three men that they were to consider themselves an official commission to visit the remote Crimean peninsula, where Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire were at war against Russia. The commission’s assignment was to discover just how modern Europeans fought their wars. Davis wanted to know about logistics (including camel transport), about medical provisions, and about artillery, especially a “secret weapon” the British were said to have, a rifled cannon with a radical elliptical bore dubbed the “Lancaster gun.”

Delafield and Mordecai were recognized experts in their fields, but Davis had chosen McClellan, a promising officer who had yet to make his mark, over Robert E. Lee, the most distinguished engineer in the U.S. Army. In fact, Lee was both surprised and disappointed at being passed over. Clearly, there was something about McClellan that impressed people well beyond any actual achievements.

In the end, the trio of commissioners produced very little of value as a result of their tour of observation—though McClellan, inspired by a European military saddle he saw, modified its design slightly and produced a prototype that the U.S. Army quickly adopted. Soon, the “McClellan Saddle” became the cavalry standard. Later, he also introduced the shelter tent—popularly known as the “pup tent”—to the army, and he translated and edited the French bayonet and drill manuals for American use. But concerning modern warfare, which should have been the central object of the commission’s study, neither McClellan nor his colleagues took away any significant insights. Nevertheless, feeling himself propelled by his own rising star, McClellan did not think twice before haughtily lecturing the secretary of war on precisely how the U.S. cavalry should be reorganized. Davis, who had been impressed with McClellan, now chafed at what he took to be his insolence. The two exchanged curt letters, and before the end of 1856, Captain George Brinton McClellan tendered his resignation from the United States Army.

In January 1857, McClellan, out of uniform now, was hired as chief engineer for the Illinois Central Railroad at the splendid yearly salary of $3,000. Within two years, he was vice president of the company and, in the course of his work, became acquainted with Abraham Lincoln, who had been engaged by the railroad off and on since 1853 as a high-level attorney. McClellan also came to know Chicago private detective Allan J. Pinkerton, whom he hired to investigate a series of train robberies that had plagued the railroad. He would call on Pinkerton during the war to furnish intelligence during his major campaigns.

In 1860, McClellan left the Illinois Central to become president of the eastern division of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad. Armed with a spectacular $10,000 salary, he resumed his pursuit of Ellen Marcy. In actuality, she had already accepted the proposal of A. P. Hill. This, however, provoked a campaign from both her parents. Her father warned her that Hill was a poor man as well as a Southerner, who supported slavery. Her mother took a more dramatic approach, disseminating rumors, which she knew would come back to her daughter, to the effect that Hill suffered from a sexually transmitted disease. To his credit, when McClellan became aware of the rumor, he wrote Mrs. Marcy to defend Hill, whom he called an honorable man and even a dear friend. Nevertheless, between the prospect of poverty, slavery, and VD, Ellen Marcy at last changed her mind. She accepted McClellan’s proposal, and, in a transport of joy, he ratified in his own mind what he had long believed: God had a very special plan for him. He even became a devoted member of the Presbyterian Church.

Then, in April 1861, after the fall of Fort Sumter, he also became a member, once again, of the United States Army. He reentered the force initially as major general of Ohio volunteers, but the next month was commissioned a major general of regulars and assigned to command the Department of the Ohio. The only army officer senior to him was Winfield Scott himself.

Scott, Lincoln, and McClellan himself had every reason to believe that he would perform admirably. Gallant in battle, a brilliant West Point graduate who had seen European warfighting close up, and, as a railroad executive, versed in the military potential of rail transportation, the commander his soon-to-be adoring soldiers would nickname “Little Mac”—he stood five-foot-eight, but his disproportionately short legs made him seem much shorter overall—seemed nevertheless to tower head and shoulders over the great majority of officers, Union or Confederate.

As commander of Ohio forces, McClellan was assigned to a theater of war removed from the eastern seaboard, where the most intense action was about to take place. His mission was to clear out Confederate resistance in western Virginia, an area with strong Union sympathies (which, sometime after Virginia seceded, would break away and declare loyalty to the United States as the state of West Virginia). He scored easy victories against small forces at Philippi on June 3 and Rich Mountain on July 11, which moved The New York Times to predict (in a most peculiar turn of phrase) that McClellan, “wise and brave,” had “a future behind him.”

Appointed in the wake of Bull Run to command what would become the Army of the Potomac, he basked in public clamor for a hero and savior but hardly rushed to become either. Instead of leading his army straight into battle, he devoted the rest of the summer and early autumn of 1861 to building it, organizing it, and training it. At the same time, he went about the work of transforming Washington into a fortress city, ringing it with forty-eight strong points and a number of full-scale forts. Collectively, the capital’s defenses bristled with nearly five hundred cannon, many of which, doubtless, would have been of more use in the field. But President Lincoln did not complain. He knew that to lose Washington to a Confederate attack would be to lose the war. Besides, the press had taken to calling “Little Mac” the “Young Napoleon,” and who was the president, installed in the White House by a mere electoral plurality, not a majority, to argue with popular acclaim?

If McClellan was popular with the public, he made himself adored by his troops. He secured for the Army of the Potomac the best equipment, accommodations, and food he could requisition. He mingled with his men, demanding much of them in training and drill but also developing an extraordinary rapport. In an age that regarded soldiers as so much cannon fodder, McClellan made it clear that he cared about his troops—and it was no act; he really did care about them.

Even as he drilled and trained the soldiers he had, McClellan sent appeal after appeal to General Scott to lay aside the “Anaconda,” his strategy of slow strangulation through naval blockade while gradually building up an army of invasion, and instead hurl everything into one force, namely the Army of the Potomac. As it approached one hundred thousand men, it was already the largest single military formation on the continent, but what McClellan insisted on having was a force of 273,000 and an artillery park of some six hundred guns. General Scott had come of age during the Napoleonic Wars, and he was a great admirer of Napoleon, having spent much of his early career in an effort to bring Napoleonic tactics and doctrine to the United States Army. Yet he knew enough about Napoleon to understand that the strategy and tactics of Austerlitz and Marengo would not work in the context of a civil war. Victory, he believed, had to be conceived in more than military terms. He did not want to pound the South into submission—such pounding would only make the people more determined in their resistance—but instead strangle and starve it, sapping both their will and their ability to fight before everything had been destroyed. Hence the blockade. McClellan, in contrast, believed that God had anointed him the Young Napoleon, and he needed all those men to stage one grand Napoleonic battle, an American Austerlitz that would crush the army of secession in a single blow.

To McClellan’s credit, the notion of fighting an apocalyptic battle that would end the rebellion by wiping out its army did have the same objective as Scott’s Anaconda: to end the war quickly and in a way that would do as little harm to the people of the South as possible. But it was based on the assumption that, once the Confederate army had been defeated, the people would end their rebellion. He took Lincoln at his word that the war was not a crusade against slavery, but a fight to restore the lawful Union. Neutralize the rebellion’s army, therefore, and the Union would be restored. Unlike McClellan, Scott believed that the source of this civil war ran much deeper, which meant that the war could be won only by making it difficult or impossible for anyone, soldier or citizen, to continue fighting. In any case, both Scott and Lincoln understood that McClellan’s request for a single force of nearly three hundred thousand men was impractical (if not impossible) for at least two reasons. First, it would take an inordinately long time to assemble and train such a force without committing it to battle. The Confederates would doubtless use this time to win victories intended to sap the will of the North to continue the war. It was unthinkable not to take aggressive action against the rebels as soon as possible. The army of the South could not be permitted to invade the North at will while generals bided their time building an idle army. Second, no single American general had ever tried to command a force so large. Even Napoleon himself discovered that the massive army he led into Russia in 1812 was beyond effective command. There was no reason to believe that this “Young Napoleon” would have fared better.

So the message to McClellan was to fight with the army he had, yet to this message McClellan wordlessly replied by continuing to train it rather than commit it to battle. As the tension over McClellan’s reluctance to fight increased, this officer who had such rapport with subordinates and soldiers turned bitterly against the one commander who was above him. He spoke openly of Winfield Scott as “a traitor, or an incompetent,” complaining that he was being forced to “fight [his] way against him.” Scott heard the complaints. Old and tired, he had no desire to challenge McClellan and therefore tendered his resignation to the president. Lincoln refused to accept it, but then he began to hear—albeit never directly from the Young Napoleon himself— that McClellan meant to resign if Scott did not step down. The rumors increased in volume and intensity. If Old Fuss and Feathers remained general-in-chief, McClellan, for the good of the nation, would lead a military coup!

Lincoln convened an emergency Cabinet meeting on October 18. Scott’s resignation had been tendered; the Cabinet decided the president had better accept it. And so he did. The change of command would become official on November 1, but McClellan had immediate authority to act as chief.

What, then, would George McClellan, now general-in-chief of the U.S. Army, do with his unchallenged authority?

Far less than anyone expected.

On October 19, he sent a single division under Brigadier General George A. McCall to Dranesville, Virginia, not to fight a battle, but to gingerly probe Confederate movements there and around Leesburg. This accomplished, he immediately ordered McCall back to the division’s main camp at Langley, Virginia, a few miles from the capital. No shots had been fired. In the meantime, he dispatched Brigadier General Charles Stone on another timid mission, to stage what he called “a slight demonstration” that was intended to provoke a Confederate response. In obedience to the tentative tone of the order, Stone sent a small force across the Potomac at Edwards Ferry. When the Confederates failed to react to this, he pulled the unit back but simultaneously ordered the commander of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry to send a twenty-man night patrol to reconnoiter the enemy position. In the darkness, Captain Chase Philbrick, the inexperienced leader of the patrol, mistook a stand of trees for Confederate tents and withdrew to regimental headquarters to report them. With a force of three hundred, Colonel Charles Devens attacked the trees at dawn on October 21. Realizing Philbrick’s error, but having crossed the river with his raiding party, Devens decided to wait for instructions from General Stone before he turned back. Stone responded by sending the rest of 15th Massachusetts—350 more men—to join the raiding party and march with it toward Leesburg for a reconnaissance there. In the meantime, Edward Dickinson Baker, a U.S. senator and a Union colonel, arrived in Stone’s camp. The general bade him welcome and promptly dispatched him to find out just what Devens was doing. Stone entrusted him with the authority either to withdraw the troops from Virginia altogether or to send in more.

While he was riding to Devens’s position, Baker learned that a skirmish was under way. Itching for a fight, he ordered as many troops as could be quickly rounded up to cross the Potomac. Possessing more experience as a senator than as a colonel, he had not stopped to consider that very few boats were available to transport troops across the river. This resulted in a trickle of forces from one bank to another, even as the fighting heated up on the Confederate side of the river, at a place called Ball’s Bluff, a thickly wooded, steep-sided hill thirty miles upriver from Washington. As the fire intensified, Baker was hit and fell dead, the only serving U.S. senator killed in action before or since.

Product of McClellan’s timid, tentative orders from on high, the battle suddenly exploded, catching the mass of Devens’s men, about 650 of them, huddled atop the steep bluff, without room to maneuver. The shortage of boats that had impeded the arrival of reinforcements now bottled up the retreat back across the Potomac. Frantic troops were trapped on top of Ball’s Bluff as well as between the bluff and the river.

That is when the 17th Mississippi Regiment arrived, charged up the bluff, and drove all the Union boys headlong down its steep slope. At bayonet point, the men ran, many leaping from the bluff, landing atop one another. Men impaled themselves grotesquely on the bayonets of those who had jumped before them. In an ecstasy of fear, soldiers piled into their pitiful few boats, overloading and swamping most of them. Soon, the lazy current of the Potomac carried the drowned and bloodied bodies to Washington.

Ball’s Bluff was not a big battle, not compared to Bull Run or the titanic struggles that were yet to come; 223 Union troops were killed, 226 wounded, and 553 captured. But its effect on the psyche of the Lincoln government was devastating. The death of Senator Baker, a close friend of the president’s, hit hard. The same Congress that fretted over a McClellan coup now speculated that Baker had not been killed in battle so much as assassinated in a conspiracy to undermine the Union. Although the Constitution exclusively assigns the president as commander in chief of the armed forces, Congress immediately created a Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War to look over the president’s shoulder. Without consulting Lincoln, the committee haled General Stone to the Capitol, demanding that he explain the Ball’s Bluff disaster. Unsatisfied with what it heard, the committee ordered Stone’s arrest and imprisonment on “suspicion” (he was never actually charged) of treason.

Had the committee worked back from Stone, the failure of Ball’s Bluff would have landed at the feet of the Young Napoleon himself. But the injustice meted out to Stone was an undeserved vindication for his commanding officer. With Stone neatly scapegoated, McClellan emerged from his biggest battle yet defeated but unscathed.

As the Civil War entered its second year, the Army of the Potomac, gigantic and magnificent, had almost nothing to show for itself. When Lincoln had made him general-in-chief of the U.S. Army, McClellan assured him, “I can do it all,” then, that evening as almost every evening, he sat down to write to his wife. “Who would have thought,” he mused, “when we were married, that I should so soon be called upon to save my country?” Despite the inaction, the Union public, most of it, still looked to the Young Napoleon for salvation. To the west, in Tennessee, in a theater of the war most people thought of as secondary to the battlefields of Virginia, the Battle of Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862) had just produced some thirteen thousand Union casualties, killed, wounded, and captured, earning Ulysses S. Grant widespread opprobrium and giving the public someone other than McClellan to blame for the tragic state of the war’s conduct.

But on January 31, 1862, President Lincoln had issued his “General War Order No. 1,” directing McClellan to begin an offensive against the enemy no later than February 22. When McClellan missed this deadline, Lincoln, despite continued support for McClellan among the public as well as from his own soldiers, relieved him on March 11 as general-in-chief of the armies, returning him to command of the Army of the Potomac only. The president hoped this sharp slap would prompt him to advance from Washington to Richmond. As Lincoln saw it, the logic of attacking Richmond directly was this: Menacing the capital of the South would force the Confederate armies to come to its defense, which meant that they would have to pull back and yield territory to Union control. Moreover, in the process of withdrawing, the armies would be vulnerable; turning one’s back on an enemy was always dangerous.

But McClellan had a different idea. Instead of advancing overland against Richmond, he proposed transporting the entire Army of the Potomac by steamers down the Chesapeake Bay to the James River for an amphibious landing south of Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston’s lines at Manassas, site of the Bull Run battle. By this movement, he intended to outflank Johnston’s army, forcing it to pull back from Washington, which would free up reinforcements from the defense of the capital to join the Army of the Potomac in the field. With his force thus augmented, McClellan promised to carry out his attack against Richmond. Lincoln believed this approach was overly cautious. He understood that the longer McClellan waited to menace Richmond, the more time the Confederate armies would have to strengthen the city’s defenses and the harder a target the Confederate capital would become. Nevertheless, pressured by subordinate officers who idolized McClellan, Lincoln endorsed the plan.

Neither Lincoln nor McClellan—who should have known better—figured on how much time would be consumed in embarking on a vast amphibious operation. McClellan was just getting under way when he learned that Johnston had left Manassas and marched south, to the Rappahannock River, closer to Richmond. When McClellan and his army finally reached Manassas and inspected the abandoned Confederate trenches there, they found them bristling with what they dubbed “Quaker guns,” logs painted dull black to mimic cannon. “Our enemies,” a reporter wrote, “like the Chinese, have frightened us by the sound of gongs and the wearing of devils’ masks.”

Of course, McClellan could point out that the enemy had withdrawn, yielding territory without firing a shot. The fact, however, was that Johnston was deliberately luring McClellan farther from his sources of supply and reinforcement to fight the consolidated bulk of the Confederate army in its home territory. Had McClellan followed Lincoln’s original orders and attacked Richmond directly, he would have faced a much smaller enemy force.

McClellan had delayed in large part because he believed that the Confederate army vastly outnumbered him. Although he had been trained as an engineer to deal with hard facts, as a combat commander those very facts were consistently magnified in his imagination into wild overestimates of enemy numbers. In an effort to obtain accurate estimates, he extensively employed Allan J. Pinkerton, whose network of spies fed him an endless stream of numbers, all, unfortunately, as far off the mark as his own imagination. The figures Pinkerton delivered were inflated by factors of two or three, sometimes even more.

Unable to accept the fact that he actually outnumbered Johnston all along, McClellan decided to continue avoiding a frontal attack on Richmond. Instead, he proposed to ferry his troops south to Fort Monroe, near Newport News and Hampton Roads, in the southeastern corner of Virginia. This would take him south of Richmond, so that he would advance north toward this objective, moving across the Yorktown Peninsula, which separated the York River from the James. His rationale was that by attacking Richmond from the south, he would force the Confederate capital’s defenders to maneuver toward the north, which would present an opportunity to envelop both Richmond and the Confederate army in Virginia. The Young Napoleon dubbed the operation the Peninsula Campaign, echoing, intentionally or not, Napoleon Bonaparte’s celebrated though ultimately failed “Peninsular War.” But planning the biggest amphibious operation in American military history to that time consumed precious days and weeks, during which Johnston further consolidated his position, making it a much tougher nut to crack.

In the Battle of Fair Oaks during the Peninsula Campaign, McClellan hired balloonist Professor Thaddeus S. Lowe to do battlefield reconnaissance and observation from his tethered balloon Intrepid. The hydrogen-filled captive balloon seemed to McClellan a promising alternative to the rickety observation towers commanders often constructed, especially for artillery spotting.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

On April 9, 1862, a supremely frustrated Lincoln wrote a letter: “It is called the Army of the Potomac but it is only McClellan’s bodyguard. . . . If McClellan is not using the army, I should like to borrow it for a while.” He never sent it, but instead folded it and put it in his desk drawer.

In the meantime, at Yorktown, McClellan, as usual concluding that he was badly outnumbered, decided to lay siege to the Confederate line rather than storm it. By the time McClellan set up his siege, Johnston had withdrawn all but fifteen thousand men from Yorktown. The wily Confederate general John Bankhead “Prince John” Magruder marched these men back and forth and back and forth to give the illusion of far greater numbers. Although he commanded some ninety thousand men, McClellan was thoroughly intimidated. He could have swallowed Magruder’s entire command. Instead, he wasted a month, during which Robert E. Lee greatly strengthened the fortifications of Richmond, continuing to make it an ever more formidable objective.

In one of the Peninsula Campaign battles, Seven Pines (May 31–June 1, 1862), General Johnston was so badly wounded that Robert E. Lee replaced him. A jubilant McClellan wrote to Lincoln that Lee was “cautious . . . weak . . . and . . . irresolute.” But after going up against him in the so-called Seven Days Battles (June 25–July 1, 1862), he found out otherwise. At great cost to both sides—greater to the Confederacy than to the Union—Lee pushed McClellan northward, away from Richmond. The Peninsula Campaign cost the Army of the Potomac a total of sixteen thousand killed and wounded, lives spent in losing ground. McClellan sought to defend his performance by arguing that Lee’s casualties were much higher, totaling nearly twenty thousand. Yet the fact was that morale remained high in the South, while it eroded in the North. When McClellan protested that Lincoln and his secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, had withheld from him the reinforcements that he needed, Lincoln responded by putting McClellan under Major General John Pope, who was assigned command of a catchall force called the Army of Virginia, which effectively subsumed the Army of the Potomac and all other forces in and around Virginia. It was a much-deserved vote of no confidence against McClellan, but it resulted in protest and grumbling from the multitude of officers and men intensely loyal to him, and when Pope suffered a catastrophic defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 28–30, 1862), Lincoln formally restored McClellan to full command of the Army of the Potomac on September 1, 1862.

Some in Lincoln’s Cabinet protested. The president admitted that while McClellan was competent in the defense, he had “the ‘slows,’” which made him “good for nothing for an onward movement [offensive campaign].” Yet, Lincoln continued, he possessed “beyond any officer the confidence of the army.” For this reason, despite the deficiencies Lincoln knew only too well, he believed that McClellan’s “organizing powers” had to be “made temporarily available until the troops were rallied.” More bluntly, he concluded: “There is no man in the army who can lick these troops of ours into shape half as well as he.”

Of his reinstatement, the Young Napoleon wrote to his wife: “Again I have been called upon to save the country.”

And now that country needed saving more than ever before.

On September 5, Robert E. Lee went on the offensive, marching across the Potomac and invading Maryland. The invasion plan was laid out in Lee’s Special Order No. 191, which he distributed to his chief lieutenants, including Stonewall Jackson, who had the order copied for General Daniel Harvey Hill. This copy was somehow discarded by Hill or lost before he received it, and on September 13, 1862, Union private W. B. Mitchell, 27th Indiana Infantry, while scrounging on what had been Hill’s campsite, ran across a bunch of cigars wrapped in a piece of paper. Mitchell was most interested in the cigars, but he took time to examine the document, recognized that it might be important, and passed it up the chain of command. When McClellan received it, he exclaimed, “Here is a paper with which, if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home.”

According to the plan, Lee intended to divide his forces—always a risky move in enemy territory. It was now up to McClellan to devise a counterattack that would defeat Lee in detail, before his divided forces could reunite.

Wonderful!

And then the familiar habits of doubt once again assailed George McClellan, who, as usual, fully believed he was massively outnumbered. He also took to heart a warning from the new army general-in-chief, Major General Henry Wager “Old Brains” Halleck, that this “lost order” might be a trick. Instead of making a decisive counterattack, therefore, McClellan timidly sent forces to probe three gaps in South Mountain on September 14. Stiff resistance from Hill bought Lee enough time to establish the main part of his army west of Antietam Creek, near the town of Sharpsburg. Still, McClellan almost managed to pull out of the situation a decisive victory with a planned three-pronged assault designed to hit both of Lee’s flanks in preparation for a coup de grace attack on Lee’s center. The plan was sound, but a combination of McClellan’s continued timidity and the inability of his subordinates to execute the plan in a coordinated manner caused it to falter when the attack stepped off on September 17.

Of the nearly 75,500 men McClellan committed to battle, 2,108 were killed, 9,540 were wounded, and 753 were captured or went missing. Lee, who commanded no more than 38,000, saw 1,546 killed, 7,752 wounded, and 1,018 captured or missing. From a tactical point of view, McClellan secured a draw. Viewed strategically, however, Antietam was a Union victory because McClellan succeeded in ending the invasion by driving Lee off the field and out of Maryland. But McClellan had missed a much larger strategic opportunity, nothing less than the destruction of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which surely would have hastened the end of the Civil War. Although sick with yet another disappointment, Lincoln seized on what limited success McClellan had given him. With his general, Lincoln proclaimed Antietam a victory and used it as the occasion, to proclaim on September 23, 1862, the emancipation of the slaves throughout the Confederacy.

Looking from the Emancipation Proclamation and back to George McClellan, Lincoln urged him to return to Virginia. McClellan responded that he needed time for the Army of the Potomac to recover from Antietam, then let more than a week pass without taking action. On October 1, the president wrote a formal order, commanding McClellan to “cross the Potomac and give battle to the enemy.” Still, the general did nothing. A week later, Lincoln demanded to know why he had not obeyed the order. McClellan testily responded that his cavalry horses were exhausted. “Will you pardon me for asking,” the president shot back, “what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigues anything?”

McClellan at last got under way but moved so slowly that Lee easily interposed his Army of Northern Virginia between the approaching Army of the Potomac and Richmond. On November 5, the Union’s new general-in-chief, Henry Halleck, sent McClellan a telegram: “On receipt of the order of the President, sent herewith, you will immediately turn over your command to Major General Burnside. . . .” It was all over for the Young Napoleon.

Civil War field photographer Alexander Gardner turned his camera on this Union burial crew at work after the Battle of Antietam.

U.S. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

George Brinton McClellan never admitted failure. For the rest of his life, he portrayed Antietam as a great victory and any defeats he had suffered earlier as the result of Washington’s refusal to furnish him with the men he demanded.

Viewed more objectively, on the positive side, McClellan had indeed taken a heavy toll on Confederate manpower, and while the North, with its greater wealth and much larger population, could make up the losses it incurred, the South could not. If the Civil War were evaluated solely as a war of attrition, McClellan did produce significant gains. Additionally, he transformed a dispirited rabble into a genuine army—only to expose that army to one brutal heartbreak after another.

On the negative side, McClellan failed to win the war, which, more than once, he might have done. Despite the waste of lives and missed opportunities, he remained popular with his men—decreasingly so with the public—and his relief and replacement created an abundance of bad blood in the army that may well have contributed to the difficulties that beset Ambrose Burnside and culminated in the catastrophic defeat he suffered at Fredericksburg (December 11–15, 1862). In November 1864, McClellan, a Democrat, tried to defeat Lincoln’s reelection bid, but lost by a wide margin. After resigning his commission, he traveled in Europe for a time, worked as chief engineer for the New York City Department of Docks (1870–1873), was a trustee and subsequently president of the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad (1871–1872), then served as governor of New Jersey (1877–1881). He was only fifty-eight when he suffered a fatal heart attack on October 29, 1885.