The initial campaign was called the Warsaw–Lodz Operation after its somewhat limited aims. For Zhukov’s 1st Byelorussian Front this meant breaking out of the Maguszev bridgehead, eliminating the German forces in the area between Warsaw and Radom, and then pushing forwards via Lodz to Posen to form a line extending north to Bromberg and south towards Breslau, which Marshal Ivan Koniev’s 1st Ukrainian Front should by then have reached in its clearance of Upper Silesia. Nothing was planned in detail beyond that stage, for the outcome of the type of breakthrough battle envisaged could not be gauged with any accuracy.

Koniev began the offensive with his 1st Ukrainian Front on 12 January, followed by Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky with the 2nd Byelorussian Front on the 13th sweeping northwards on Danzig and Gotenhafen, and lastly Zhukov joined in with the 1st Byelorussian Front on the 14th. By the time Zhukov attacked, the 9th Army opposing him was fully alert, but to little avail. By the end of the following day the 9th Army’s defensive system had been destroyed and Zhukov’s 1st and 2nd Guards Tank Armies were through and advancing up to 100 kilometres beyond their start lines. To the south Koniev’s forces were enjoying similar success with a rapid advance.

The Soviet progress was aided by the weather. There was little snow to hinder them, and as the frozen ground and iced-up waterways could take the weight of the infantry and light artillery pieces, they did not have to stick to the roads and thus built-up areas could easily be bypassed. The movement was so swift that the Soviets were constantly catching the Germans unprepared, their defences unmanned. Consequently, on 17 January, the day the two ‘Berlin’ Fronts drew abreast and Warsaw fell, Stalin ordered Zhukov to reach the Bromberg–Posen line by 3 or 4 February.

The Soviet advance continued with increasing speed. Posen was reached on the 22nd and Bromberg fell the next day, a full week ahead of schedule. However, Posen was an important communications centre, where seven railway lines and six major roads met, and it would not be taken that easily. It was a genuine nineteenth-century fortress city with an inner citadel and a ring of massive forts manned by a garrison of some 60,000 troops of various kinds. But a single city could not be allowed to hold up the Soviet advance, so the leading troops pressed on while Colonel-General Vassili Chuikov of the 8th Guards Army was detailed to supervise the reduction of the fortress with four of his divisions and two from the slower-moving 69th Army that was following behind. The siege of Posen was to last until 23 February, and it proved to be an important delaying factor for the Germans.1

The armoured vanguards of each corps consisted of a reinforced brigade operating 30 to 40 kilometres ahead of the main body, while the infantry armies formed similar vanguards from their own integral armour and motorised infantry units to operate up to 60 kilometres ahead of the main body. These were flexible distances, of course. As the fighting was done almost exclusively by the vanguards, the main body followed in column of route and only deployed when larger enemy forces were encountered, thus enabling the infantry armies to maintain virtually the same pace as the armoured ones.

The Soviet advance, however, was hampered by the limited quantities of fuel, ammunition and supplies it could carry with it, for its basic supply system depended almost exclusively on the railways with local distribution by trucks, and, as the following accounts reveal, the depots were still east of the Vistula. The Soviet railway gauge was wider than the European, and the German invasion of the Soviet Union had therefore entailed adapting the tracks to suit their trains; the Soviets simply reversed this process as they reconquered lost territory and advanced into Poland and Germany. As Colonel-General Chuikov put it:

The logic of combat is inexorable; it accepts neither justifications nor plausible excuses if during the fighting the logistical services fail to supply the frontline troops with everything necessary.

We can find any number of valid explanations and excuses why on reaching the walls of Posen we did not have enough heavy guns to pulverise the enemy fortifications. But the fact remains that the assault on Posen dragged out for a whole month instead of the several days allotted for the operation by the Front Command.

It was not a simple matter to adapt the logistical services to the troops’ heightened rate and depth of advance. The Front Commander’s orders and his determination could not solve the problem. Within a few days the advancing troops had considerably outdistanced their supplies. Motor vehicles had to make longer runs. As a result fuel consumption increased. And there was no magic to turn 100 trucks into 300. You’ve got to have them, man them and provide the maintenance for them, which means additional repair shops and whole repair complexes. In a word, combat operations demanded that the logistical services perform their functions faultlessly, for a miscalculation or blunder in the transport operations could cost thousands of lives.

But the closer we approached the Oder, the deeper we penetrated into Germany, the more complex became the supply system.

Here is an example. Railways were a constant source of worry. The absence of a standard railway gauge during the initial stage of our advance into Germany adversely affected the supply of the advancing troops. The oversight was put right eventually, but time was lost.

In order to save fuel, half the motor vehicles making empty runs from the front were towed to their destination. All captured fuel was registered and distributed under strict control. Captured alcohol was mixed with other components and used as fuel, and all serviceable captured guns and ammunition were used against the enemy.2

Colonel A.H. Babadshanian, commanding the 11th Tank Corps of the 1st Guards Tank Army, wrote:

Our tank troops attacked without pause for breath by day and night, in fog and in snow. Only the lack of fuel and ammunition could check our attack. The communication routes had extended to almost 400 kilometres, the supply depots having remained on the east bank of the Vistula. The railways were not functioning and the road bridges over the river had been destroyed. There was petrol for motor vehicles in the captured German camps but no diesel. Often combatant units were stuck for days.3

On 26 January, the day his troops crossed the 1939 German border, Zhukov submitted a plan to the Soviet High Command, which was approved the following day. It stipulated that the 1st Byelorussian Front’s forces were to reach the line Berlinchen/Landsberg/Brätz by 30 January. It should be noted, however, that the Soviet High Command warned the 1st Byelorussian Front that in order to provide reliable cover for the Front’s right flank against possible enemy attacks from the north or north-east, one army augmented by at least one tank corps had to be kept in reserve behind the Front’s right flank.4 Zhukov went on to say:

By the same day the tank armies shall gain control of the following areas:

The 2nd Guards Tank Army: Berlinchen, Landsberg, Friedeberg; the 1st Guards Tank Army: Meseritz, Schwiebus, Tirschtiegel.

Upon reaching this line, the formations, particularly the artillery and the logistical establishments, shall halt, supplies be replenished and the combat vehicles put in order. Upon full deployment of the 3rd Shock and 1st Polish Armies, the Front’s entire forces shall continue the advance on the morning of the 2nd February, 1945, with the immediate mission of crossing the Oder in their drive, and shall subsequently strike out at a rapid pace towards Berlin, directing their main effort at enveloping Berlin from the north-east, the north and northwest.5

In Zhukov’s orders issued on 27 January he stated:

There is evidence that the enemy is hastily bringing up his forces to take up defensive positions on the approaches to the Oder. If we manage to establish ourselves on the western bank of the Oder, the capture of Berlin will be guaranteed.

To carry out this task each army will detail one reinforced rifle corps…and they shall be immediately moved forwards to reinforce the tank armies fighting to secure and retain the position on the west bank of the Oder.6

Zhukov continued his forward planning and the next day further details emerged. Once across the Oder, the 5th Shock Army was to thrust towards Bernau, north-east of Berlin, the 8th Guards Army towards Buckow, Alt Landsberg and Weissensee, and the 69th Army towards Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, Boossen and Herzfelde, all three armies operating between the water boundaries formed by the Finow Canal in the north and the Spree River in the south.

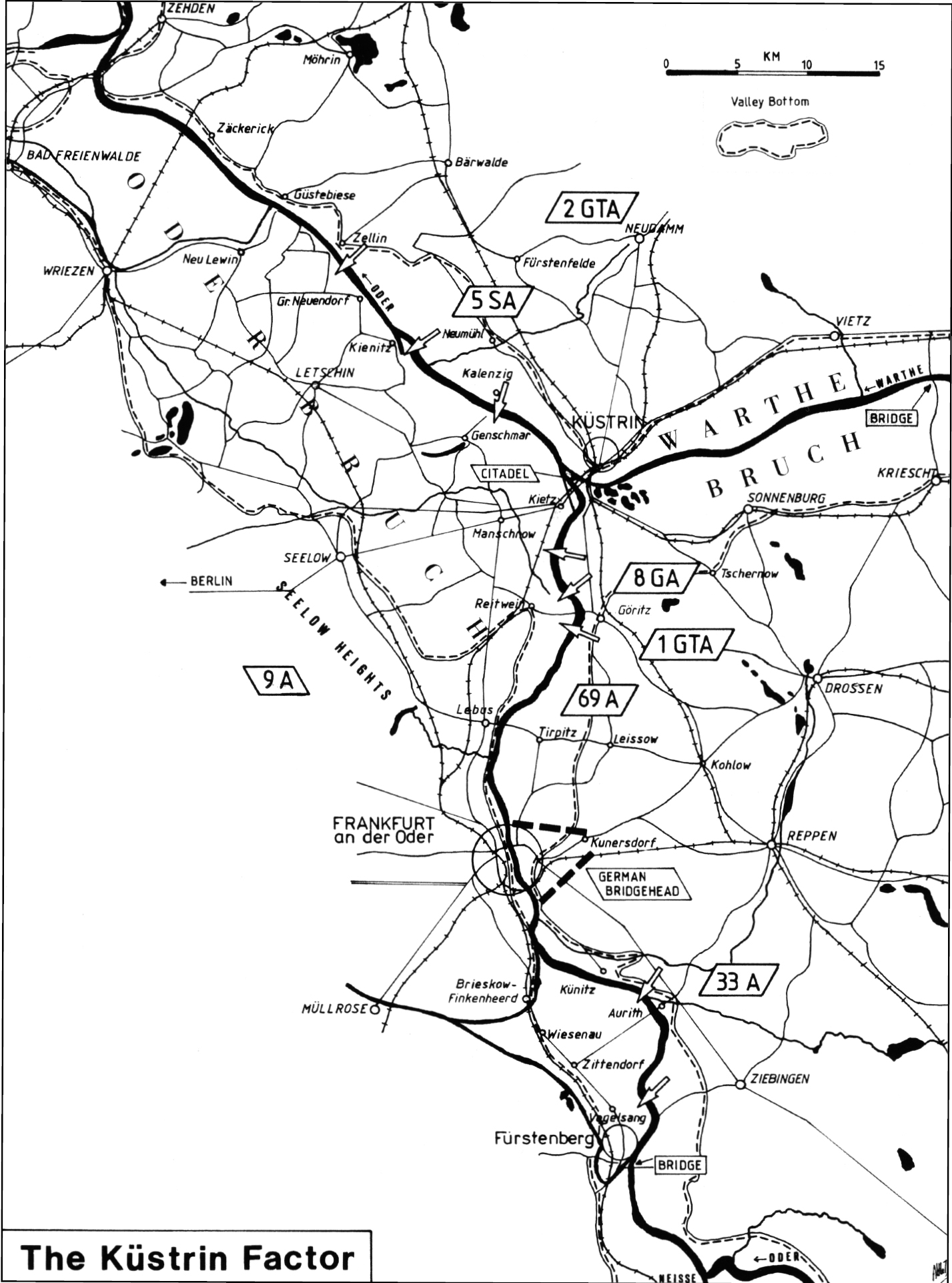

No mention of Küstrin was made in these orders, yet it had the only road and rail bridges across the Oder for a considerable distance in either direction. The only available alternatives to the Küstrin bridges were the road bridges at Frankfurt, 27 kilometres to the south, and at Hohenwutzen, 46 kilometres to the north, and the railway bridges at Frankfurt, 30 kilometres to the south, and at Zäckerick, 38 kilometres to the north. Presumably Zhukov expected these bridges to be blown in the face of his advance, thus obliging his men to use their own resources to cross the river.