CHAPTER 1

THE FOOT THAT MOVES THE PEDAL

Horace M. Dobbins’s California Cycleway

The foot that moves the pedal is the foot that moves the world.” This was supposedly a favorite saying of Horace M. Dobbins, one of Pasadena’s most famous citizens. He was best known for the “California Cycleway,” an elevated wooden bike path above the streets of Pasadena. His goal was to extend this bikeway to downtown Los Angeles, but he was unable to obtain funding to do so. However, the Cycleway continues to inspire interest in bicycling, particularly as an alternative to the automobile, to this day.

HORACE DOBBINS

Horace M. Dobbins was born on August 29, 1868, the fifth child and youngest son of Richard J. and Caroline Dobbins. The Dobbinses were an old-money family who lived on a one-hundred-acre estate in Cheltenham, near Philadelphia. Richard was a master builder, responsible for many landmarks in Philadelphia, including the Public Ledger Building, the House of Corrections and Memorial Hall, one of several structures for the Centennial Exhibition in 1876.

Richard enrolled young Horace in the Cheltenham Military Academy. But Horace found school difficult, as he preferred to teach himself. This frustrated his father to no end. “Oh Horry, you’ll never amount to anything,” he would scold.

The Dobbins family moved to Pasadena’s milder climate permanently in 1886, as Richard was in poor health. Richard died in early 1893. Horace spent a few years in Portland, Maine, and then in San Diego before settling in Pasadena in 1895.

Dobbins took part in Pasadena’s civic life with enthusiasm. He served on the Pasadena Board of Trustees and was president of the Pasadena Board of Health and the Tournament of Roses Board and was active in both the Pasadena and Los Angeles Chambers of Commerce. He also became president of the Pasadena Hospital Association, which built the first successful hospital in Pasadena.

PASADENA AND THE BICYCLE CRAZE

Throughout the 1800s, transportation was limited to walking, horseback, horse-drawn carriages for those who could afford them or, in the larger cities, horse- or mule-drawn streetcars. Although bicycles had existed since the early 1860s, they were the old-fashioned types, with a very high front wheel (for speed). Accidents in which the rider was thrown over the handlebars were common.

By the late 1880s, a new type of bicycle had appeared on the market. Unlike the “high-wheelers,” this bicycle featured two equally sized wheels, pneumatic tires and a chain drive between the pedals and the back wheel. This new version was known as the “safety bicycle,” as it was much safer to ride than the high-wheeler. It kicked off what became known as the “Bicycle Craze” across the United States, as the bicycle became a mode of transportation almost anyone could afford and use.

More and more people rode bicycles, and bicycle sales increased. Much cheaper to own and maintain than a horse, it provided a new freedom to its riders. This was especially true for women, who reveled in the independence provided by the bicycle. Indeed, many historians credit the Bicycle Craze for partially inspiring the women’s liberation movement. Advocate Susan B. Anthony said, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman on a wheel [bicycle]. It gives a woman a feeling of freedom and self-reliance.”

Songs like “Daisy Bell (Bicycle Built for Two)” and “The Bicycle Girl” emanated from music hall and fancy parlor alike. However, sales of pianos and other items fell dramatically as people bought bicycles instead. Bicycling replaced other activities, such as reading, going to the theater or attending church.

Southern California, because of its mild weather, reportedly had more bicycles per person than any other place in the world. Pasadena, in particular, had an active cycling community, several cycling clubs and a high-quality racing track. However, Pasadena lacked good roads for people who used bicycles as a means of transportation rather than as a sport. Cyclists had to contend with dirt roads full of wagon ruts, railroad tracks and horse manure. Riding on the sidewalk was not an option; local mounted police would catch and fine any offenders. Only one road, in very poor condition, joined Pasadena and Los Angeles, making bicycle travel between the two cities difficult.

DOBBINS BUILDS THE CYCLEWAY

Although Horace Dobbins was not an avid cyclist, he was a great dreamer of solutions to problems. One day, while traveling between Pasadena and Los Angeles, he was distressed by the poor road and decided that an improved roadway for bicycles was needed between the two cities.

In August 1897, Dobbins formed the California Cycleway Company. He was the president of the company, and former California governor Henry H. Markham was vice-president.

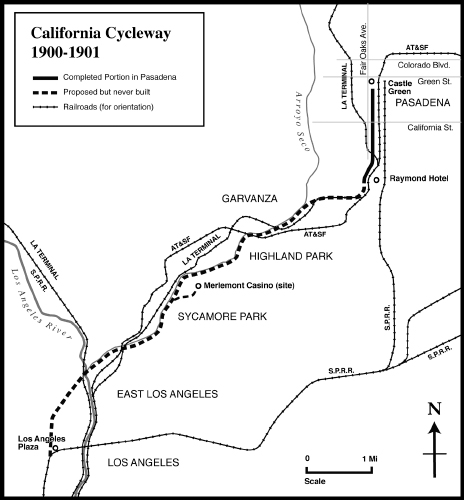

The company sold stock for twenty dollars per share. These funds, along with money Dobbins had received in an inheritance, were used to purchase a six-mile right-of-way along the Arroyo Seco, a small waterway winding between Pasadena and Los Angeles.

The Cycleway would be an elevated roadway made of Oregon pine, rising from fifteen to fifty feet above the ground. It would be wide enough for two cyclists riding abreast in each direction. The franchise also required that electric lights be placed along the roadway.

It would feature gentle grades, no more than about 3 percent, allowing for nearly effortless pedaling. It would pass through a tunnel under the Elysian Park hills north of central Los Angeles and then end near the Plaza (Olvera Street). From there, cyclists could use one of several paved roads for continued travel.

Merlemount Casino drawing. From the Pasadena Daily Evening News.

Pasadena Cycleway construction. Courtesy of the Archives, Pasadena Museum of History.

The Cycleway’s most famous feature was to be the Merlemount Casino, located on a hill near the halfway point in Garvanza (now part of Highland Park). This “casino” would not be a gambling facility, but rather a place where cyclists could take a break. The casino would feature shops, restaurants, separate waiting rooms for ladies and gentlemen and a Swiss dairy providing milk for thirsty cyclists.

California Cycleway’s proposed route. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

Work on the Cycleway began on May 6, 1899, with a groundbreaking ceremony at the Casino site. “The earth turns as we turn the earth,” declared Dobbins as he dug into the ground.

The magazines of the day wrote of the Cycleway and the Merlemount Casino as if they had already been completed. Writers imagined the completed, lighted Cycleway as a “gleaming serpent” snaking between Pasadena and Los Angeles after dark.

THE CYCLEWAY OPENS

The Cycleway’s first segment, which ran from Dayton Street, south of the Green Hotel, over an alley between Raymond and Fair Oaks Avenues, south to Columbia Street, near the Raymond Hotel, opened for business on January 1, 1900. Although nearly everyone’s attention was focused on the eleventh annual Rose Parade, an estimated six hundred cyclists used the Cycleway that day.

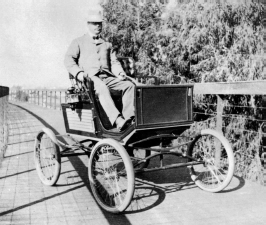

At first, everyone enjoyed the Cycleway. Even Dobbins’s young daughter, Dorothy, would ride it on her tricycle. The Cycleway franchise also allowed for motorcycles and other motorized vehicles. Dobbins himself traveled on the Cycleway in an early automobile.

On April 16, the Pasadena Board of Trustees elected Dobbins as president, making him mayor of the city.

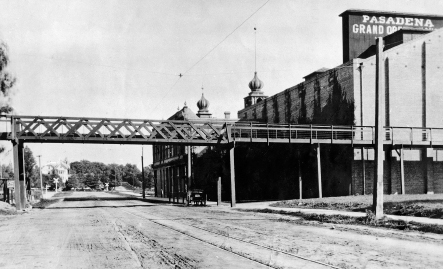

Cycleway crossing at Opera House. Courtesy of the Archives, Pasadena Museum of History.

END OF THE CYCLEWAY

Unfortunately, Dobbins’s ambitious project was doomed before the year’s end. The Bicycle Craze was winding down, as people abandoned bicycles for other modes of transportation. Henry Huntington and others were expanding their electric trolley networks across Southern California. These streetcars and electric interurban trains would be the dominant mode of transportation for about the next twenty years.

The road improvements that bicyclists demanded also helped usher in the age of the automobile. Horseless carriage pioneers such as Henry Ford had used bicycles as a base for their experimental self-propelled vehicles. By now, the first primitive automobiles had appeared on the roads, and their numbers would only increase in coming years.

Mostly children and athletes now rode bicycles. Prospective Cycleway investors lost interest. Funding to complete the Cycleway beyond Pasadena to Los Angeles, and to build the Casino, never materialized.

The Cycleway Company planned to collect tolls to help finance further expansion. Tolls were ten cents for a one-way trip and fifteen cents for a round trip. Although a tollbooth was placed at the Dayton Street entrance, it was often unmanned, and cyclists rode for free, hurting Dobbins financially.

Work stopped on the Cycleway in October 1900. Dobbins admitted, “Yes, I have concluded that we are a little ahead of the time on this cycleway. Wheelmen have not evidenced enough interest in it, and so we will lie still for a time and use it for an automobile service.” Inadvertently, he had forecast the Arroyo Seco Parkway (Pasadena Freeway), to be built nearly forty years later. He continued, “But those vehicles [automobiles] are not yet common or perfect enough to jump into business. We will preserve our valuable rights of way and then later construct the cycleway on a more substantial plan.”

Cycleway ticket booth at Green Hotel. Courtesy of the Archives, Pasadena Museum of History.

Dobbins riding in an automobile on Cycleway. Courtesy of the Archives, Pasadena Museum of History.

Attitudes toward the Cycleway changed. The citizens of Pasadena voted to acquire land to build Central Park and did not want the elevated structure through it. So, the city acquired the Cycleway structure in the proposed park and demolished it.

THE BRIDGE OF SIGHS

After the Cycleway structure had been removed, Dobbins pondered what to do with his right-of-way. Meanwhile, Henry Huntington’s Los Angeles and Pasadena Electric Railway, which became part of the vast Pacific Electric (PE) in 1901, planned a new “short line” between Pasadena and Los Angeles. This new line would cut thirty minutes from the travel time between the two cities. However, the project would require rebuilding the bridge carrying Fair Oaks Avenue over the Santa Fe and Los Angeles Terminal Railroads.

PE planned to replace the existing fifty-two-foot-wide bridge with a new structure of the same width. The City of Pasadena, however, wanted an eighty-two-foot-wide bridge matching the width of Fair Oaks Avenue. Walter Raymond, owner of the nearby Raymond Hotel, also wanted a wider bridge. But the proposed bridge would have taken four feet of Dobbins’s property.

Dobbins sued the railway, demanding $15,000 in compensation. PE stopped work on the bridge but continued building the line elsewhere. By October 1902, PE was running short line cars from Los Angeles all the way to the Fair Oaks bridge. From there, passengers had to deboard, walk across the bridge and reboard another trolley for continued travel into Pasadena.

The press labeled the affair the “Bridge of Sighs,” after the infamous prison bridge in Venice, Italy. In Pasadena, though, most of the sighing was done by the passengers, who had to put up with the inconvenience of walking across the bridge to change cars.

On November 22, 1902, both parties, weary of the time it was taking for the matter to be heard in the courts, settled. Dobbins received an undisclosed amount in exchange for the necessary land for Pacific Electric to build the wider bridge.

THE PASADENA RAPID TRANSIT COMPANY

Dobbins continued to dream about other uses for his right-of-way. At first, he considered building an elevated road for automobiles, but he decided on an electric interurban railway instead.

On January 1, 1909, Dobbins formed the Pasadena Rapid Transit Company and sold stock for $100 per share. The Pasadena Rapid Transit Company’s line would start at an elaborate terminal building near Fifth and Broadway in downtown Los Angeles. It would then run through an underground tunnel to the Los Angeles Plaza before going onward to Pasadena on an elevated structure. The line, featuring two sets of tracks for local and express trains, would carry passengers between the two cities in twelve minutes.

As with the Cycleway, Dobbins was unable to sell enough shares to finance the rail line. A group of Belgians reportedly considered investing but backed out shortly before World War I started.

After the war, Pasadena residents, frustrated with what they thought was poor Pacific Electric service to Los Angeles, decided to revive Dobbins’s proposed rail line as a municipally owned service. A measure to issue construction bonds was placed on the April 1919 ballot. While the measure won a majority of votes, it fell short of the two-thirds needed to pass. Project boosters tried again in 1920, but this time, the measure was overwhelmingly voted down. PE, reading the writing on the wall, improved its Los Angeles–Pasadena service.

Dobbins continued his civic activities. In 1909, he became president of the Sixth District Agricultural Association, which managed Agricultural Park in Los Angeles. The park was in poor condition and hosted gambling and other undesirable activities. In 1913, the park was renamed Exposition Park; museums and gardens replaced the racetracks and saloons.

Although he lacked financial and political support to realize them, Dobbins never completely gave up his transportation dreams. He invented and patented a “Lateral Support Monorail” in 1922 and a “Duplex Monorail” in 1929.

In late 1932, Dobbins’s relatives in Philadelphia asked him to return to Philadelphia to manage the financially troubled Elks Hotel, which was located on land owned by the Dobbins family. He renamed it the Broadwood Hotel and served as its resident manager for twenty years. Upon retiring, he bought a John Alden yacht and sailed from the East Coast to California via the Panama Canal. He settled in San Pedro, where he traded the boat for an elaborately decorated grand piano. He spent the rest of his life playing the piano and designing yachts but felt lonely because he had outlived so many of his friends.

On September 21, 1962, at the age of ninety-four, Dobbins passed away at Huntington Hospital in Pasadena, the same hospital he helped build in the late 1890s.

EPILOGUE

Although the Cycleway was never completed, it inspired several notable transportation facilities.

In 1938, the State of California built Southern California’s first freeway, the Arroyo Seco Parkway, along the banks of the waterway. The parkway opened in 1938 and has carried increasing volumes of traffic over its curving path ever since. Contrary to popular belief, the parkway was not built over the Cycleway’s right-of-way but rather on the opposite bank of the Arroyo Seco. (A short portion of the right-of-way exists adjacent to the Metro Gold Line tracks along Fair Oaks in South Pasadena.) Still, Pasadena historians consider Dobbins the “Father of the Freeway” for building one of the first grade-separated transportation facilities in the United States.

The Cycleway north from Raymond Hotel. Courtesy of the Archives, Pasadena Museum of History.

Interest in bicycling has increased in the past few decades, as people seek more healthful and environmentally friendly methods of transportation. The County of Los Angeles built a bike path in the concrete-lined bed of the Arroyo Seco in 1983. Unfortunately, several problems plague this path. Rainstorms close the path and leave it strewn with debris for several days afterward. Portions of the path are hidden from street view, posing a security risk. And lastly, a path in the streambed is contrary to the greater environmental goals of returning waterways to their natural states.

Pasadena bicycle advocate Dennis Crowley and Will Dobbins, a grandson of Horace Dobbins, founded a group named California Cycleways in 1996. This organization planned to build an elevated cycleway, similar to the one planned in 1887, between Pasadena and Los Angeles. Construction and maintenance would be financed by tolls. Unfortunately, Crowley’s death in 2008 has put a damper on this project. More likely is a new bike path along the Arroyo Seco’s banks.

The closest realization of Dobbins’s dream happened on June 15, 2003, when the Pasadena Freeway/Arroyo Seco Parkway was closed to motor vehicle traffic but opened to pedestrians and cyclists. Arroyofest, sponsored by the Urban and Environmental Policy Institute of Occidental College, was a joint effort of several environmental, community and bicycle advocacy groups (including Crowley’s California Cycleways). As three thousand bicyclists and thousands of pedestrians walked and biked along the eerily silent freeway lanes, residents of South Pasadena and Highland Park heard birds singing instead of traffic noise and noticed the lack of pollution from automobile exhaust. Additionally, residents of the communities along the Arroyo Seco learned of transportation alternatives and connected with their neighbors.

Since October 2010, the City of Los Angeles has supported CicLAvia, a biannual event closing selected city streets to automobiles. More than 100,000 bicyclists, walkers, joggers, skaters and other non-motorized users enjoyed CicLAvia in October 2012.

While the Bicycle Craze may have died down at the turn of the twentieth century, interest in bicycling has never been stronger. Perhaps this rediscovery of the bicycle as a means of transportation will encourage a visionary to build a network of elevated cycleways, as Horace Dobbins attempted in 1900.