CHAPTER 2

“IT’LL PUT THE PACIFIC ELECTRIC RAILROAD IN A MUSEUM!”

Joseph W. Fawkes’s Aerial Swallow

FAWKES’S FOLLY

One day in 1907, a small crowd gathered in a Burbank apricot orchard. However, the people did not come to buy fruit. Instead, all attention was focused on a sharply dressed man standing next to an odd-looking object. Upon closer inspection, the strange contraption appeared to be a cigar-shaped vehicle, roughly forty feet long and vaguely resembling a streetcar. It was covered with a shiny metal and featured an airplane-style propeller on one end. The vehicle hung from an overhead steel beam via several wheels and pulleys.

The man, named Joseph Wesley Fawkes, gestured excitedly at the vehicle and shouted to the crowd, “My Aerial Swallow will travel at a top speed of sixty miles per hour. It’ll take you from Burbank to Los Angeles in ten minutes. Why, it’ll put the Pacific Electric Railroad in a museum!”

The crowd murmured politely, but skepticism hung in the air. Many in Burbank called him “Crazy Fawkes.” He had a reputation for being, at best, eccentric. At worst, he was considered standoffish and opposed to anything supported by other people in the city.

Fawkes hopped into the front of the vehicle and started the engine. The propeller spun faster and faster until the Aerial Swallow lurched forward. The crowd murmured in guarded approval.

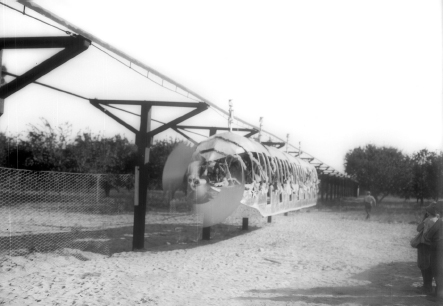

Fawkes’s propeller-powered Aerial Trolley, or Aerial Swallow. Courtesy, California Historical Society Collection at the University of Southern California. Title Insurance and Trust/C.C. Pierce Photography Collection, CHS-5028.

The Aerial Swallow traveled about 150 feet. Suddenly, due to engine vibrations, it began to shake itself apart. Fawkes stopped the engine, but his audience, losing interest, began leaving. Mutters of “Crazy Fawkes” and “Fawkes’s Folly” filled the air as the crowd dispersed.

JOSEPH WESLEY FAWKES

Joseph Wesley Fawkes was born in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1861. His father, Joseph Walker Fawkes, was a prolific inventor who developed and patented several agricultural implements, including a steam-powered plow. During the 1860s and 1870s, the Fawkes family moved around Iowa and into Illinois, finally settling in Chicago. The elder Fawkes owned an electrical goods factory in Chicago until 1887, when the business was lost in a fire.

After the fire, the Fawkeses moved to California, settling in Burbank on the land they had purchased in 1884 from David Burbank, the city’s namesake. They purchased more land for farms and fruit orchards. But Joseph Wesley Fawkes was no farmer. He spent most of his time writing poetry, painting in oils or traveling around the world. He often expressed views in opposition to other citizens and was frequently found squabbling with most of his family. Most people in Burbank chose to avoid him.

He stood out in other ways as well. While most men wore dungarees and farmers’ clothing, Fawkes’s store-bought suits were always impeccably neat. He waxed his mustache and went about town in a fancy carriage pulled by two high-stepping horses. As an added touch, a pair of spotted Dalmatian dogs followed the carriage.

Fawkes inherited his father’s inventive talents, so he spent much time at the drawing board. In 1901, he patented an electrically illuminated advertising sign. Proceeds from the sales of this device financed his travels and his next invention.

THE AERIAL SWALLOW

Although unknown, it’s highly possible that one of Fawkes’s trips to Europe took him to Wuppertal, Germany, where a suspended monorail, the Schwebebahn, had started operating in 1901. This monorail may have inspired him to build a suspended monorail in Burbank.

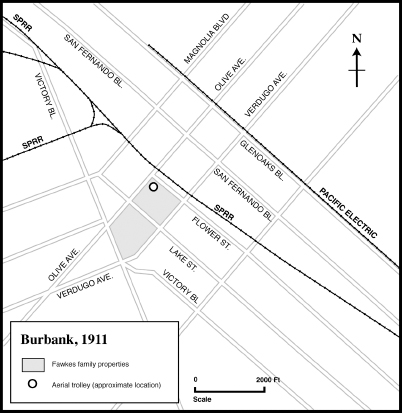

Fawkes built a half-mile overhead rail in his orchard, near Lake Street and Olive Avenue, and then constructed his Aerial Trolley Car or Aerial Swallow. On one end was an aircraft propeller, powered by an air-cooled Franklin engine. Aluminum, a comparatively rare metal at the time, encased the forty-foot-long vehicle. The car, which hung from the overhead rail by four wheels, could seat fifty-six passengers. At first, Fawkes planned to add tanks of lighter-than-air gas to the vehicle to improve handling, but he never did so.

Fawkes boasted that the Aerial Swallow would revolutionize transportation. He envisioned extending the monorail along the Los Angeles River to the central city and threatened to build the route “over Mount Hollywood” (in present-day Griffith Park) if the City of Los Angeles refused him permission to build along the riverbank.

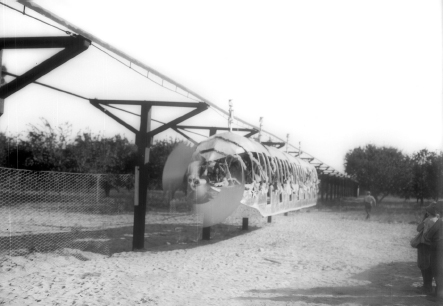

Site of Aerial Swallow in Burbank. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

Fawkes’s Aerial Swallow. Courtesy, California Historical Society Collection at the University of Southern California. Title Insurance and Trust/C.C. Pierce Photography Collection, CHS-5013.

PEOPLE OF BURBANK: NOT INTERESTED

The citizens of Burbank, who were generally put off by Fawkes’s antics, were even less impressed by his monorail. Instead, they focused their attention on the transportation system everyone in Southern California wanted a part of: the Pacific Electric “Red Cars.”

Although PE had linked Los Angeles and Glendale since 1904, access for Burbank consisted of a trip to Glendale in either a horse-drawn carriage or the “Auto Stage,” an early form of bus. Both required travel over bumpy, dusty, unpaved roads. Southern Pacific’s passenger trains between Burbank and Los Angeles were also available.

The citizens of Burbank knew that a PE line meant more than transportation; it would be a catalyst for the development, growth and future prosperity of their city. And unlike the Aerial Swallow, the PE was known as a dependable and proven transportation system.

At first, PE refused to extend its rails to Burbank, citing its low population of five hundred. Under continued pressure from the city, PE relented and agreed to build a spur track between Glendale and Burbank—as long as Burbank provided $48,000 before the end of 1910. The citizens immediately began raising funds, while farmers along the proposed route set aside parts of their lands for the rail right-of-way. A number of Burbank landowners lived as far away as San Diego and Riverside, then about one day’s journey over primitive roads. Volunteers made the long trip from Burbank to ask these distant landowners to contribute a few thousand dollars each before the end of the year.

Money in hand, PE began work on the track. On September 6, 1911, the first Red Cars made their forty-five-minute run from Los Angeles to Burbank.

FAWKES’S FABULOUS FOURTH

Undeterred by the lack of public support, Fawkes continued to improve his monorail. He obtained a patent in 1911 and formed the Aerial Trolley Car Company. He sold shares in the company for $100; the funds would build not only the monorail but also residences, warehouses, farms and even amusement parks along the route.

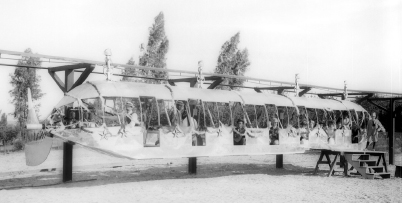

Visitors take a ride on the Aerial Swallow. Courtesy, California Historical Society Collection at the University of Southern California. Title Insurance and Trust/C.C. Pierce Photography Collection, CHS-5015.

In 1912, he felt that the Aerial Swallow was ready for a public exhibition. On July 4, Fawkes held an extravagant outdoor picnic at his orchard. There was food, music and, after dark, fireworks. But the center attraction was the monorail. Guests clambered aboard the vehicle from a makeshift platform of planks and sawhorses. A sharp whistle blew, and the car moved along the short test track.

The top speed was about three miles per hour, not only slower than the Red Car but also slower than walking. Fawkes’s guests must have asked themselves whether the Aerial Swallow would ever be capable of whisking passengers to Los Angeles in ten minutes, as Fawkes had promised.

Since the test vehicle had a propeller on only one end, it had to be pushed back by hand to the starting point to provide multiple trips. The propeller produced an air current, making the open-sided car drafty and uncomfortable.

Although Fawkes’s guests enjoyed the food and fireworks, few were impressed enough to invest in the Aerial Trolley Car Company. The event received little coverage in the press; the Los Angeles Times printed only a short paragraph, while the Burbank Review ignored it entirely.

In spite of Burbank’s tepid response, Fawkes continued to promote the Aerial Swallow. He used it to move baskets of apricots across his orchard. Once in a while, a curious person would come to the orchard and take a ride.

SANTA MONICA

Fawkes offered to build an Aerial Trolley in the city of Santa Monica in November 1911. The Santa Monica route would operate along Fremont Street (now Pico Boulevard) from the beach to the city’s eastern border, with a future extension eastward to downtown Los Angeles. Six tracks would be provided, allowing for local and express services. Again, the inventor promised phenomenal speeds and travel times: 120 miles per hour and ten minutes to Los Angeles.

In April 1912, he applied to the City of Santa Monica for a franchise. Fares would be five cents for a trip within Santa Monica and ten cents to Los Angeles. A short film of the Aerial Swallow running on its test track played in a local theater, generating interest in the monorail.

However, businesses and property owners on Fremont Street expressed their opposition to the Aerial Trolley, leading the city council to reconsider awarding the franchise. Fawkes remarked, “I was amazed at the stand taken by council in reconsidering the franchise advertisement, but I can see where they stood with all the opposition which developed. I think they were needlessly alarmed.” He continued to insist that the Aerial Trolley would be a practical transportation system and not merely an “amusement feature.”

On June 4, the city council voted to grant Fawkes the franchise. He invited the citizens of Santa Monica to visit his property in Burbank and see the monorail on its test track. However, the Fremont Street protesters—now joined by the chamber of commerce, the board of trade and the school board—continued to state their opposition to the project. The city council postponed awarding the franchise on June 6.

Support for the monorail continued to grow, with people in Santa Monica’s Fairview Heights neighborhood especially enthusiastic. Several Santa Monicans visited the test track in Burbank, and nearly four hundred people signed a petition in favor of the project. The Evening Outlook newspaper, which held a strong pro–Aerial Trolley position, complained that it was receiving too many letters in favor of Fawkes.

Finally, on July 2, the city council approved the franchise. But to everyone’s astonishment, Fawkes decided not to build the monorail. He complained that the franchise did not prohibit the building of a competing surface trolley along the same route. He also objected to the franchise requirement to carry public officials for free. So, Fawkes slunk back to Burbank, to the relief of the opposition.

Meanwhile, PE had improved several of its routes serving Santa Monica, and the citizens of Santa Monica, as did their counterparts in Burbank, looked to the Red Cars as their primary means of transportation.

“CONSOLIDATION JOE”

Fawkes also found himself at odds with Burbankians over whether Burbank should be a separate incorporated city or annex itself to the city of Los Angeles. In 1908, Los Angeles had started building a 223-mile-long aqueduct to bring water from the far-off Owens Valley to a fast-developing, thirsty Southern California. Although Burbank had its own water wells, Fawkes thought that the city would be better off if it could access water from the aqueduct. Because the legislation authorizing construction of the aqueduct prohibited Los Angeles from selling or giving away water to other cities, if Burbank or any other city wanted aqueduct water, its only choice was to be annexed to Los Angeles.

Despite Fawkes’s best efforts, the citizens of Burbank voted overwhelmingly to incorporate as an independent city on July 8, 1911. On November 5, 1913, the first cascades of Owens Valley water arrived in Los Angeles. Most of the small towns in the San Fernando Valley became a part of Los Angeles about two years later. As public interest in his Aerial Swallow waned, Fawkes again pushed for Burbank to be consolidated with Los Angeles.

After an unsuccessful court battle with the city in early 1920 over water bonds, Fawkes again agitated for annexation. He presented a petition with 432 signatures to the city clerk, placing the annexation question on the November ballot. Again, the people voted against annexation. Fawkes, making accusations of ballot box stuffing and other irregularities, petitioned for a special election. A district court of appeal denied the request in 1922, the same year Fawkes unsuccessfully ran for county supervisor.

In preparation for the June 1925 election, Fawkes held several pro-annexation meetings. A meeting held at his home was delayed by an electrical outage. Again, the pro-annexation measure failed to receive sufficient votes. Upon the defeat of the measure, the anti-annexationists held a big party. They lit a bonfire, hung Fawkes in effigy and buried him in a mock grave. “Here lies the body of Consolidation Joe,” read the fake headstone.

EPILOGUE

Joseph Wesley Fawkes passed away on June 27, 1928, leaving little more than the Aerial Swallow, which rusted in place until it was hauled away as scrap in 1947. Meanwhile, the Pacific Electric’s service to Burbank continued until 1956, when buses replaced the interurban trains. Borrmann Steel relocated from Oakland to the site of the monorail in the 1960s and operates (as the Borrmann Metal Center) to this day.

Although the Aerial Trolley Car was not a success, it remains part of the lore of Burbank. Interest in monorails as viable public transportation has continued; however, no one has yet proposed a propeller-driven monorail based on Joseph Wesley Fawkes’s design.