CHAPTER 3

FROM NICKEL-SEEKERS TO SMART SHUTTLES

The Jitney in Southern California

It is the summer of 1915. A man stands at a Los Angeles Railway stop on Main Street in downtown Los Angeles, waiting to board a “Yellow Car.” Several overcrowded streetcars have already passed by. Suddenly, from the Model Ts and other automobiles going past, one veers toward the stop and halts.

Attached to the front of the car is a sign: “Jitney Bus. Main and 58th Street. 5 Cents.” The auto is filled with riders, and four people are standing on the running boards, holding on for dear life. The driver calls out to the man: “Need a ride?”

The man thinks for a moment. The offer seems risky. Getting into an automobile full of strangers? Then another overcrowded streetcar passes by. Anxious to go home, the man steps toward the overloaded Ford, nickel in hand.

THE JITNEY ARRIVES IN LOS ANGELES

The first automobiles appeared in Los Angeles as early as 1897. Until the advent of the Ford Model T and other mass-produced vehicles, automobiles were regarded as curiosities and, later, as “rich man’s toys.” The average person would probably never ride in an automobile other than a taxi. Most people either walked or used rail transit, such as Henry Huntington’s Los Angeles Railway and the Pacific Electric, controlled by the Southern Pacific Railroad. PE and LARY had a near monopoly on transportation in Los Angeles. Streetcars were often crowded and sometimes ran late. Newspaper articles painted the streetcar companies as an unresponsive “Trolley Trust,” maximizing profits over passenger convenience by allowing overcrowding and ignoring passenger complaints.

The first jitney drivers, such as L.P. Draper of Los Angeles and A.H. Kirkendall of Long Beach, began to offer rides to people waiting at streetcar stops in 1914. Drivers and streetcars charged the same fare: a nickel. At first, people called the vehicles “five cent autos.” “Jitney” was common slang for a nickel coin, and eventually, the automobiles themselves were called “jitneys.”

Within a year, the jitney phenomenon had spread across most of the United States. Starting a jitney service in most cities was laughably easy. All anyone needed was an automobile and driver’s license (as well as, in some cities, a professional chauffeur’s license).

There were both full-time and part-time jitney drivers. Often, someone driving to work would pick up and drop off people along the way, charging a fare. “Moonlighting” taxi drivers or private chauffeurs used their cars as jitneys without their employers’ knowledge.

As more people discovered that jitney driving was a source of “easy money,” more and more full-time jitney drivers appeared on the streets. It was a gold rush. Used Ford Model Ts and similar automobiles, in good or not-so-good condition, flew off the lots. These vehicles were not designed for continuous use, so the drivers switched to larger, heavier touring cars or custom-built bus bodies on truck chassis.

Some jitney drivers liked to be called “jitneurs,” a French-sounding combination of “jitney” and “chauffeur.” Less complimentary names included “auto-sniper” and “nickel-seeker.”

EVERYONE LOVES A JITNEY RIDE

Because the vehicle made fewer stops along the way, jitney riders enjoyed faster service. Jitneys boarded and let off passengers at the curb rather than in the middle of the street, as streetcars did. Sometimes, jitney drivers deviated from their route to drop passengers off closer to their destination, an impossibility for a streetcar. The rubber-tired automobiles also offered a smoother ride than the steel wheels and jointed rails of the streetcar lines. And jitneys just seemed more fun to ride.

“What a queer lot we are anyway!” Courtesy of the Jay N. “Ding” Darling Wildlife Society.

Newspapers and magazines were filled with poems and stories about jitneys. Novelty songs such as “Gasoline Gus and His Jitney Bus,” “Jitney Jim” and “I Didn’t Raise My Ford to Be a Jitney” became popular.

Many people chose the jitney as a way of striking back at the streetcar companies’ overcrowded cars, inconvenient service and unresponsive management. And during the tough times of the mid-1910s, jitneys provided a source of income to the men (and occasionally women) behind the wheel. Government regulations were almost nonexistent, so drivers could work as much or as little as they wanted.

THE JITNEY BECOMES A MENACE

Although many people loved jitneys, this new mode of transportation caused serious problems on the streets of Los Angeles.

Competition for fares caused drivers to operate without regard for the safety of either their passengers or other people on the street. Drivers raced one another to streetcar stops, running over pedestrians or colliding with other vehicles. Los Angeles’s vehicle accident rate rose by a startling 60 percent.

Jitneys were sometimes dangerously overloaded. The same passengers who had bitterly complained about having to stand in a streetcar had no problem piling into crowded jitneys, sitting on laps or hanging on to the outside of the car. Drivers defended overloading: the more people they could carry, the more money they made.

Drivers skimped on maintenance. Cars with bald tires, bad brakes and other mechanical problems created additional safety hazards. Most jitney drivers lacked insurance, making it difficult or impossible for persons injured in an accident to recover damages. Police checks frequently turned up drivers who were unlicensed, underage, illiterate or otherwise unqualified.

Jitneys operated according to the whims of their drivers rather than the needs of their riders. If a driver felt he was not making enough money along a given route, he might simply turn around and head back downtown for more passengers, stranding passengers on the outer portion of the route. The more unscrupulous drivers would falsely state that the car had broken down and would need to return downtown, only to order their current load of passengers out of the vehicle.

Drivers gouged riders on fares. A streetcar strike might send the usual nickel fare soaring to as high as a dollar. Bad weather might be an excuse to boost fares or to not drive at all, leaving people without transportation.

Antisocial behavior was common among jitney drivers. Fistfights broke out among drivers competing for fares. Racial discrimination was prevalent; jitney drivers often refused to carry black citizens and other minorities.

The overcrowded jitneys were an ideal place for pickpockets to ply their trade. Some drivers were criminals who supplemented their income by robbing passengers. The close confines of the jitneys attracted gropers and sexual harassers. Women were warned not to use the jitneys unaccompanied, especially at night. And there were the fake jitneys, used to attract passengers for criminal purposes. An attitude of “anything goes in the jitneys” prevailed, giving them a bad reputation.

NOT ENOUGH NICKELS FOR BOTH OF US

At first, the streetcar companies ignored the jitneys. Streetcar company executives thought that drivers would lose interest as repair costs and depreciation ate into their profits. But as the number of jitneys increased and more people chose them over the streetcar, the streetcar companies lost money.

Jitneys concentrated on serving the busier portion of the streetcar routes near downtown, where the streetcar companies made their profit, enabling them to provide service to the less lucrative outer portion of the routes. As profits fell, the companies reduced service, laid off employees and postponed extending streetcar lines. The Los Angeles Railway considered replacing its popular five-cent flat fare with a distance-based fare system, hoping to recover the costs of serving the outlying parts of its service area.

Paul Shoup, president of Pacific Electric, declared, “There are not enough nickels used for transportation…to support the two classes of transportation.”

Hoping to sway public opinion, Pacific Electric and Los Angeles Railway emphasized the public service that their franchises required. Streetcar companies paid taxes; jitney drivers did not. Streetcar companies helped maintain the streets; jitneys just caused them to need repaving more quickly. Streetcar companies carried policemen and firemen for free and offered reduced fares for schoolchildren. Jitneys charged everyone the same price and often overcharged passengers.

The Los Angeles Times took a strident anti-jitney position, railing against the “evil of the jitney bus” in its editorials, and dutifully reported nearly every jitney accident. Businesses relying on streetcars to bring in customers sided with the rail operators. So did real estate developers, who truly owed much of their existence to the streetcar’s ability to make land accessible for development. Streetcar company management and employee unions put aside their differences and joined forces against the jitney.

By April 1917, the United States had entered World War I. The War Industries Board, encouraged by the streetcar companies, looked askance at jitney drivers duplicating streetcar service and decided they could be doing more essential work—or enlisting in the military.

Although an earlier statewide effort to regulate jitneys had failed, Los Angeles city officials placed Proposition 4 on the June 1917 ballot. The measure, if passed, would ban jitneys from the busiest streets in downtown Los Angeles. It would also require drivers to post an $11,000 bond, choose and adhere to a specified route and operate for a minimum number of hours each day.

The streetcar companies offered free rides to voters and promised raises to their employees. Not surprisingly, the proposition won.

The final blow for jitney operations in central Los Angeles came in 1918, when the city passed an ordinance forbidding jitneys from operating on any street with a streetcar route. Some jitney drivers set up shop in other parts of the city, such as San Pedro, where oversight was much less rigorous. Others found a new home in jitney-friendly suburbs such as Santa Monica or Long Beach; these jitney operations eventually became Santa Monica Municipal Bus Lines and Long Beach Transit. The new, fast-growing “auto stage” (intercity bus) industry also attracted many former jitney drivers.

Jitneys temporarily appeared in Los Angeles during transit labor disputes in 1935 and 1946.

JITNEYS OF THE 1970S: LA FRANCE AND YELLOW CAB

The streetcars made their final run in 1963 and were replaced by diesel buses. The publicly owned Southern California Rapid Transit District (RTD) replaced several privately owned transit companies and extended routes to previously unserved areas.

But Los Angeles city officials, including Mayor Tom Bradley, were looking for other ways to improve transit. They thought that legalized jitneys could supplement bus service along busy streets such as Wilshire Boulevard or provide service in poorly served outlying areas.

RTD reacted to the city’s proposal in much the same way the streetcar companies did to the “nickel autos” of the mid-1910s. Jitneys would congest streets, “skim the cream off our best paying lines” and “draw patronage from the guts of our service,” protested RTD officials. In spite of the transit agency’s complaints, the city council voted to allow two jitney experiments.

In April 1974, Fred La France, an airline operations manager, received a permit to start a jitney route between Marina Del Rey and Venice. His La France Transportation System charged twenty-five cents for a ride in a nineteen-passenger van. La France planned to expand service to Santa Monica, Westchester and Mid-City Los Angeles, but he faced opposition from RTD, Santa Monica Municipal Bus Lines and other transportation companies. Financial difficulties forced him to double his fare to fifty cents.

Yellow Cab started a jitney service on August 5. Green-colored sedans (to distinguish them from regular cabs) ran along fixed routes on Wilshire and Sunset Boulevards. The fare was one dollar—more expensive than RTD’s twenty-five cents but cheaper than a taxi. The company planned to add four more routes and replace the cabs with fifteen-passenger vans if the service was successful.

When RTD drivers went on strike on August 12, people needing transportation filled the jitneys. But after the strike ended on October 18, the jitneys lost most of their passengers to RTD’s twenty-five-cent fare. Both the Yellow Cab and La France operations ceased in November.

Even though La France and Yellow Cab were unsuccessful, advocates hoped that jitneys would return to the streets of Southern California. Activist groups in East Los Angeles, right-leaning think tanks such as the Reason Foundation and the Cato Institute and United States senator S.I. Hayakawa all expressed support for jitneys.

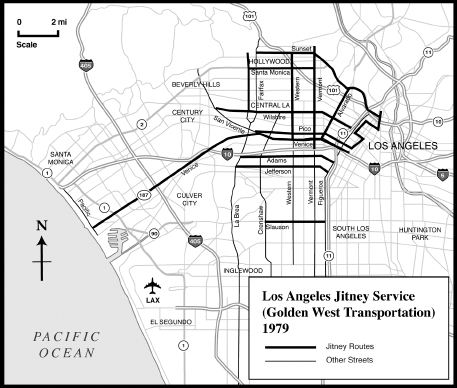

Los Angeles Jitney Service map, 1979. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

JACK’S JITNEYS

When a strike once again idled RTD buses in September 1979, Jack Ohan, president of Goldenwest Transportation, applied for and received a temporary permit from the City of Los Angeles to run jitneys along several major streets for the duration of the strike.

Twenty minivans, each hurriedly stenciled with “L.A. Jitney Service,” operated along ten routes, mostly in central and western Los Angeles. A few routes served southwestern Los Angeles, and one route replaced RTD’s downtown minibus shuttle.

Stranded bus riders crammed into the sixteen-passenger minivans. The small vehicles were not realistic replacements for RTD’s usual forty-foot buses; overcrowding and pass-ups were the order of the day. Illegal jitneys, which appeared during the strike, provided unwelcome competition.

Fortunately, the strike only lasted for six days. Once the buses returned, Ohan’s minivans disappeared from the streets. Although his jitney experiment cost him about $18,000, Ohan was happy to have served so many people during a time of need.

EXPRESS TRANSIT DISTRICT AND MAXI-TAXI

In 1982, two new companies were formed to run jitneys in Southern California. Francisco, Manuel and Aurelio Medinilla, three brothers from Mexico, founded the Express Transit District (ETD). Another company, Maxi-Taxi, was started by three Russian immigrants. (Jitneys were, and still are, common in big cities in Mexico, Russia and other countries.)

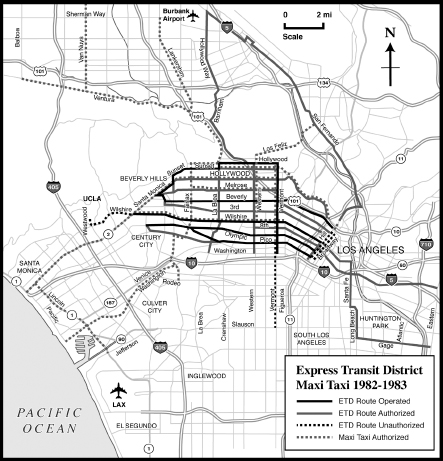

Both companies proposed routes operating between downtown and west Los Angeles, with stops in Santa Monica, Culver City and Beverly Hills. A few routes would operate in South Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley. Since the routes would cross city borders, both companies required certificates from the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). RTD, as well as the Santa Monica and Culver City municipal bus systems, objected fiercely to the upstart companies sharing their routes and bus stops. But in July 1982, CPUC gave its authorization, and soon ETD jitneys were on the roads.

Express Transit District and Maxi-Taxi, 1983. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

Although ETD was granted authority for fourteen routes, only six routes operated. Maxi-Taxi, which was authorized to run on an additional thirteen routes, went out of business before it ever provided service.

ETD’s ridership peaked at 6,500 daily boardings. Its fifteen-passenger vans were especially popular with Hispanics because of the large number of Spanish-speaking ETD drivers. ETD also provided speedier and friendlier service than the large RTD buses.

However, RTD had an advantage over the private company. In 1980, Los Angeles County voters passed Proposition A, a half-cent sales tax increase to fund a rail system and other transit projects. One provision of Proposition A held RTD bus fares at fifty cents for three years. But opposition to the proposition kept the money tied up in court battles for more than two years. Finally, in July 1982, RTD was able to get the funds and lower its fares.

ETD originally planned to charge seventy-five cents per ride. But the lowered RTD fares forced ETD to charge fifty cents as well. (RTD’s fifty-cent fare was one of the reasons Maxi-Taxi never started operating.) While ETD struggled with the reduced revenue brought on by the lower fare, RTD continued to complain bitterly about ETD vehicles blocking buses at bus stops and “poaching” its passengers.

Eventually, ETD’s lack of income took its toll. In April 1983, CPUC, responding to reports of poor maintenance, suspended ETD’s certificate. In addition, the Los Angeles County district attorney opened an investigation into ETD for alleged investment fraud. Allegedly, investors who purchased ETD vans received fake bills of sale. In some cases, the same vehicle was “sold” four or five times. The California Department of Labor expressed concern about ETD’s bus leasing program. Drivers had to “rent” their vehicles from the company and apply fares toward the rental fee, resulting in them being paid below minimum wage. Other employees, such as mechanics, were never paid.

The Medinillas allegedly returned to Mexico, and ETD went out of business.

SMART SHUTTLE: HIGH-TECH JITNEYS FOR THE 1990S AND BEYOND?

Transportation planners have struggled to design a transit system combining the efficiency of the fixed-route bus and the flexibility of the automobile or taxi. Such a system would be so popular it would pay for itself entirely from the farebox—no government subsidy needed.

This was the promise of Smart Shuttle, an idea originating with the UCLA Urban Innovations Group and later adopted by the Southern California Association of Governments. Small buses would run along major streets. Using high-tech methods such as Global Positioning Systems (GPS) and Automatic Vehicle Location (AVL), dispatchers would be aware of the location of each vehicle at all times. If a passenger needed to be picked up from an off-route location, the dispatcher could easily call the nearest vehicle and have its driver go off route to pick up the passenger and then return to the route. Although the service would operate like a taxi, fares would be closer to fixed-route bus fares.

Smart Shuttle vans in San Fernando Valley. Author’s collection.

In 1997, the Metropolitan Transportation Agency (MTA) and the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT) implemented a pilot Smart Shuttle program in three areas of Los Angeles: Koreatown, South Central and the San Fernando Valley. Although MTA provided $10 million in startup funds, Smart Shuttle was expected to be entirely self-supporting within two years.

Unfortunately, Smart Shuttle did not live up to expectations. In an attempt to match service levels to actual use, Smart Shuttle staff constantly modified routes, service areas and hours and days of operation. Riders were confused as to when the service would be available and whether or not route deviations would be allowed.

On the Koreatown and San Fernando Valley routes, Smart Shuttles simply operated like the jitneys of the 1910s, duplicating MTA bus service and carrying most of the same passengers.

Smart Shuttle never came close to supporting itself entirely from fares. MTA provided an extra $2.3 million in 1999 to keep the shuttles rolling for a little while longer. During the MTA bus strike in 2000, Smart Shuttle enjoyed increased ridership, as desperate passengers crowded onto the vehicles. After a contentious debate between MTA and LADOT as to which would be responsible for the service, all funding was abruptly cut, and Smart Shuttle stopped running in late 2001.

EPILOGUE

It is the summer of 2025. A man stands at a bus stop on Main Street in downtown Los Angeles. A continuous stream of automobiles and small vans passes by. He taps the screen of his smartphone a few times. Suddenly, a small van pulls over to the curb. The man exchanges a few pleasantries with the driver and then gets in the van. No money changes hands; payment has been handled electronically. The van zooms away.

Is this the future of public transportation in Los Angeles? Jitney advocates would like to think so. Groups concerned about those without transportation point to both the increased mobility and employment opportunities jitneys might provide. Libertarians and others ideologically opposed to tax subsidies for public transit favor replacing tax-subsidized bus and rail systems with unsubsidized jitneys.

Technology such as Internet-enabled cellphones can eliminate the need to handle cash and aid in providing background information on prospective riders and drivers. New “car services” such as Uber, Lyft and Sidecar allow riders to use applications on their cellphones to request rides, pay fares and vet drivers. These services are more similar to taxis because they cater to single riders or small groups. However, one can envision a more bus-like service, carrying larger groups of passengers. Unlike a fixed-route bus, such a service could offer route deviations, as requested by a cellphone-carrying passenger.

Jitney opponents fear that without any regulations, jitneys will congest traffic, cannibalize existing transit and pose a safety hazard to passengers and passersby alike. Obviously, a proper balance of regulation and freedom will need to be found so the jitneys of the future will provide a safe and useful form of transportation.