CHAPTER 4

“A MILLIONAIRE TWICE”

O.R. Fuller’s Motor Transit

I only have a third-grade education, but I’ve been a millionaire twice.” These were the words of O.R. Fuller. While nearly forgotten today, he was one of the big names in Southern California transportation during the early twentieth century.

He started the Motor Transit bus company with a single route between Los Angeles and Fullerton in 1916. Within a decade, it had become the largest bus company in California.

He was also a leading automobile dealer. His dealerships sold a range of vehicles, from commercial trucks to luxury Auburn and Duesenberg automobiles.

During the Depression, he turned a neglected ranch into one of the largest dairy and poultry farms in Southern California, while converting his ranch house into a first-class guesthouse attracting celebrities from far and wide.

A BOY NAMED OLIVE

Olive Ransome Fuller was born in Smith Center, Kansas, on October 5, 1880. His parents, Charles Henry Fuller and Maud Spencer Fuller, divorced shortly after he was born. Charles moved to California, where, along with his brother, Ortus, he built a large ranching business covering many thousands of acres. In 1887, Maud remarried and settled on a farm south of Wichita.

Life in Kansas was rough in the 1880s and 1890s. Droughts and snowstorms killed cattle and ruined crops. Throughout these rough times, young Ransome’s days were filled with the never-ending farm chores. He had to rise at 4:00 a.m. to work and was not finished until 8:00 p.m. This left little, if any, time for education.

O.R. ARRIVES IN CALIFORNIA

In 1898, when Ransome turned eighteen, he boarded a train to Los Angeles. Once there, O.R.—as he now liked to be called—lived with his father and worked at Pioneer Truck and Transfer. At the same time, he went to school, but apparently only for a few years, hence the “third-grade education” reference he often made much later in life.

He moved to the Olinda Ranch near Fullerton in 1905. Later that year, he married Agnes Nicolas. Although O.R. had little education, he had plenty of entrepreneurial ability. His first business was selling hay raised on the ranch. Then, with his brother-in-law, Peter, he opened the Eureka Livery Stables in Fullerton. O.R. also sold horses and mules and became a sales agent for a laundry, a wheat mill and a cement plant. He led a busy civic life as a member of the chamber of commerce. Hunting trips and horse races filled his leisure hours.

The automobile age arrived in Fullerton in about 1907. O.R. became Fullerton’s Cadillac dealer, turning the Eureka Stables into the Eureka Stables and Garage. He loved to drive all over Southern California in a Cadillac.

PIONEER AUTO COMPANY

In April 1909, O.R. sold the Cadillac dealership and moved back to Los Angeles. For about a year, he worked at Pioneer Truck and Transfer, owned by his father and his uncle, Ortus. He started the Pioneer Commercial Auto Company in 1911, selling Reliance and White trucks along with Stephens automobiles. He especially liked the Stephens Salient Six model and would take it for pleasure drives around Southern California.

One day in 1913, O.R. reacquired two trucks from a failing business. Instead of trying to resell them, he decided to use them for Pioneer Truck and Transfer’s suburban delivery service. The trucks proved to be moneymakers, as they were far more efficient than the horse-drawn wagons Pioneer still used.

O.R.’s wife, Agnes, became accustomed to life in Los Angeles, planning parties and becoming part of the city’s social life. Unfortunately, she fell ill in late 1917 and passed away in March of the following year. In 1920, O.R. married Ione Wright, a young woman from Arizona.

MOTOR TRANSIT

Many early automobile owners used their vehicles as sources of income by offering rides and charging fares. As passenger traffic increased, drivers used larger cars and then switched to bus bodies on truck chassis. These buses, or “motor stages,” operated along highways between cities and towns, competing with the railroads. California, with its mild weather and good roads, was ideal for the motor stage business.

O.R. ended up in the motor stage business by accident—literally. In 1916, he sold two White buses to the PE Stage Line, which connected Los Angeles and Anaheim via Whittier and Fullerton. After a bad accident, PE Stage Line went out of business. O.R. repossessed the buses and then decided to start a bus line of his own, assuming the route of the defunct company. He named his bus company White Bus Line, after the manufacturer of the two buses.

At first, these early bus lines operated without any regulation. Cities and counties applied their own taxes and regulations to the buses, creating a patchwork of rules. Adding to the problem was the occasional fly-by-night bus company.

The California Railroad Commission started regulating intercity buses on May 1, 1917. From then on, bus companies had to apply for, and be granted, a “certificate of public convenience and necessity” from the Commission. The agency set fares and rates, balancing the public’s desire for low fares with the companies’ need to make a reasonable profit. For bus lines operating between cities, the Commission’s orders overruled city and county regulations, although local jurisdictions could still require permits. (The state constitution exempted from Commission jurisdiction any bus companies operating totally within an incorporated city or buses operated by a municipality.)

Motor Transit bus. Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

The Commission also managed competition among bus companies. According to its regulations, the first company to serve a given route had the exclusive right to pick up and drop off passengers along that route. Any subsequent companies wishing to serve the same route had to prove to the Commission that the existing service was inadequate to meet the public’s need.

O.R., along with other bus company owners in California, formed the Motor Carriers’ Association. This organization unified the bus companies politically, enabling them to lobby for favorable legislation and low tax rates. The association also worked with local and state government agencies to prevent unlicensed and unregulated drivers, known as “wildcats,” from poaching passengers from the licensed bus lines.

STAGES ACROSS CALIFORNIA

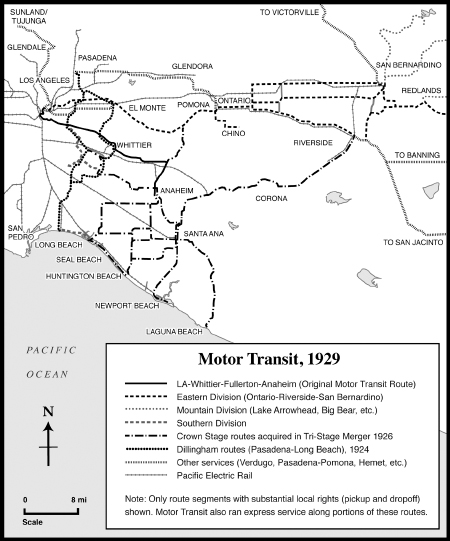

In 1919, O.R. purchased the ARG and Clark Bus Lines, transforming White Bus Line from a one-route bus company to a network of routes stretching to Ontario, Riverside, San Bernardino and San Diego. He renamed the company to Motor Transit and, to avoid street congestion in central Los Angeles, built a bus terminal at Fifth and Los Angeles Streets. The terminal also served non–Motor Transit buses.

Motor Transit bus. Courtesy Dorothy Peyton Gray Transportation Library.

About one year later, O.R. acquired the El Dorado Stage Line, which connected Los Angeles and Bakersfield. The buses traveled over the Ridge Route, forty-eight miles of steep grades and hairpin turns. Running time between the two cities was about ten hours.

Bakersfield, and its fast-growing petroleum business, provided plenty of riders. But the city also served as a connecting point to stages northbound to the San Joaquin Valley and the Bay Area. Motor Transit, along with Valley Transit (Bakersfield–Merced) and California Transit (Merced–Oakland), entered into a pooling arrangement. All three companies supplied vehicles; a Motor Transit driver would operate between Los Angeles and Bakersfield, where a Valley Transit driver would take over for the segment to Merced. Once there, drivers from California Transit would drive the bus to Oakland. Passengers wishing to continue to San Francisco could take a ferry.

Working together, the companies provided three daily round trips between Los Angeles and the Bay Area. A fourth trip was added in 1924. The fourth trip was known as the “Sun-Maid Limited,” named after the raisin-growing cooperative. Passengers on this trip received a free box of Sun-Maid raisins.

THE MOUNTAIN DIVISION

O.R., who had grown up in flat Kansas, was especially fond of the mountains near San Bernardino. He envisioned Motor Transit bus routes serving Lake Arrowhead and Big Bear.

However, the Mountain Auto Line had served the San Bernardino mountain roads since 1912. Since the Commission would not allow him to operate a competing service, O.R. decided to buy the Mountain Auto Line. Max Green, owner of the bus line, sold it to Motor Transit in 1920. O.R. put Green in charge of Motor Transit’s new Mountain Division. Eventually, Green became Motor Transit’s passenger traffic manager.

The Mountain Division may have been more trouble than it was worth. Its buses required special gear ratios, making them useless on flat roads. Passenger travel dropped off tremendously in the winter months. Heavy snowfall closed roads, detouring buses through Victorville or even shutting down service entirely. The mountain routes survived because of the freight they carried, not from passenger fares. Freight, from newspapers to auto parts, was an important part of Motor Transit’s operations on its non-mountain routes as well.

Motor Transit bus, Mountain Division. Courtesy Dorothy Peyton Gray Transportation Library.

OTHER ROUTES

Motor Transit acquired several other routes. Most of these were short, such as Pomona–Chino or Bakersfield–Taft. Longer routes served San Jacinto, Lancaster, Verdugo Hills and Victorville. Additionally, Motor Transit operated the City of Montebello’s municipal bus route along Whittier Boulevard from 1928 to 1931.

In late 1922, O.R., along with several Hollywood business leaders, formed the Hollywood Motorbus Company. The company proposed several local bus routes in Hollywood and two routes to downtown Los Angeles. However, Los Angeles’s Board of Public Utilities and Transportation strongly opposed any new bus companies serving the already congested central area, so the Hollywood Motorbus backers abandoned their effort.

If O.R. could not operate local buses in the city, at least he could make money selling buses to Pacific Electric and the Los Angeles Railway. The two rail companies bought several White buses for use on their jointly owned Los Angeles Motor Coach bus system, which served Wilshire Boulevard and other streets lacking rail. “Well, we feel a little bit puffed up ourselves over this record for we sold eighty-one White buses right here in Los Angeles to electric traction companies in one order,” said O.R. “The Pacific Electric and the Los Angeles Railway Company divided the order, and are now using these White buses in their augmented combination tram and bus service.” He also sold buses to Yosemite and Yellowstone National Parks.

O.R.’S AUTO BUSINESS

Along with Motor Transit, O.R. continued to manage his automobile and truck dealerships. Many automobile dealerships opened on “Automobile Row,” or Figueroa Boulevard south of downtown. O.R. moved the Stephens dealership there in September 1917.

Business boomed as people bought trucks and buses. The White factory in Cleveland had trouble keeping up with orders. After receiving an especially large shipment, O.R. remarked, “Business was never better. If I could only get all the trucks I want from the factory I might draw at least one long breath.”

O.R. became an authority on automobiles and Los Angeles’s growing “car culture.” He was often quoted in newspapers across California, advising motorists about engine maintenance and driving techniques. He admitted to being bewildered by the auto-related slang used by younger people in the mid-1920s. “A motor car nowadays may be a ‘bus,’ ‘boat,’ ‘wagon,’ ‘jazz cart,’ ‘buggy,’ ‘job,’ and a lot of other things,” remarked the then forty-seven-year-old O.R. “Even the motorists of the fair sex use ‘step on it’ and ‘heavy foot it’ instead of different forms of the verb, speed.”

The White Auto Company started selling Auburn automobiles in 1923. O.R. was especially fond of these cars, stating in a 1924 Los Angeles Times article, “For twenty-three years Auburn motor cars have earned a reputation among satisfied owners for long sturdy life, good performance and general high value at a reasonable price.” The Auburns were so popular that the increase in business nearly overwhelmed O.R.

In 1928, O.R. renamed the White Auto Company to the Auburn-Fuller Corporation and opened dealerships in Hollywood and San Francisco.

THE TRI-STAGE MERGER

By 1926, passengers were facing a bewildering array of bus companies, fares and service area restrictions. In order to untie this Gordian knot, Motor Transit, California Transit and Pickwick Stages, under the guidance of the Commission, divided the market among themselves, each choosing a specific area and type of service.

Under this agreement, known as the “Tri-Stage Merger,” Motor Transit gave up its long-distance routes to Lancaster, Bakersfield and San Diego and became a suburban bus line serving Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino Counties. In exchange, Motor Transit gained the rights to carry local passengers anywhere in its system. Motor Transit sold its Bakersfield route to California Transit, which would from then on connect Northern and Southern California via the Central Valley. Pickwick, which had just absorbed the Orange County routes of Crown Stages, gave up local rights along its routes in exchange for long-distance service between Los Angeles and San Diego.

About this time, bus companies across the United States merged into the national Greyhound Lines system. Southern Pacific, Santa Fe and other railroads also entered the bus business, running buses to replace poorly performing train trips.

Motor Transit system map. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

In late 1929, O.R. sold Motor Transit to Pacific Transportation Securities, a holding company owned by Greyhound, Pickwick and Southern Pacific. O.R. received $3 million for the sale and remained on the board of directors of Motor Transit. The holding company, which renamed itself Pacific Greyhound Lines, later sold Motor Transit to Pacific Electric.

O.R.’s success with his auto dealerships, along with the sale of Motor Transit, enabled him and his family to move into a new, custom-built house in Los Feliz, east of Hollywood. The Fullers shared their new neighborhood with many actors and producers, such as Cecil B. DeMille, Julia Faye and William Fox. Los Feliz was the home of several business “movers and shakers” as well. The Chandlers, publishers of the Los Angeles Times, lived across the street; D.W. Pontius, president of the Pacific Electric (O.R.’s former competitor), also lived nearby.

PE, now controlling rather than competing with Motor Transit, shortened or discontinued rail lines in places where Motor Transit provided faster or more direct service. PE curtailed some of the less productive bus routes and sold the Mountain Division back to Max Green.

O.R. AND E.L.

O.R.’s successful Auburn dealerships attracted the attention of Errett Lobban Cord, owner of the Auburn Automobile Company. Cord had also started in the automobile business at a young age. In 1924, he had bought the struggling Auburn with a low-ball, take-it-or-leave-it offer. Although his business tactics alienated many people, Cord had made Auburn profitable by 1926. Cord also acquired several companies, including Stinson Aircraft, Duesenberg Automobiles and Lycoming automobile and aircraft engines.

Cord, as enthusiastic about airplanes as he was about automobiles, entered the airline business in 1930. Century Airlines served the Midwest from a Chicago hub; Century Pacific flew from Grand Central Airport in Glendale to San Diego, Bakersfield and San Francisco. Both airlines used ten-passenger Stinson aircraft.

O.R. and Cord went into business together. Cord bought an interest in O.R.’s Auburn dealership and moved it from Figueroa Street into a new Art Deco building on Wilshire Boulevard, across the street from the Ambassador Hotel. Cord appointed O.R. president of Century Pacific.

Cord insisted that his employees work long hours at low wages. It was no different for the Century pilots, whom Cord considered “glorified chauffeurs” and paid at about half the normal rate. At first, the pilots were glad to have any job they could get and suffered in silence. But when Cord announced further wage cuts in 1931, the Chicago-based pilots went on strike.

Auburn-Fuller Company building, Wilshire & Mariposa, Los Angeles, 1932. Los Angeles Examiner Collection, Department of Special Collections, University of Southern California.

Cord kept expenses low, not only to compete with rail fares but also to offer a low bid on a U.S. Post Office airmail contract. However, Cord’s business practices made him no friends with the government. U.S. Post Office officials noted that the pilots were so demoralized they flew unsafely, threatening the stability of the entire airline network. During the strike, Cord often referred to the striking pilots as “Reds” and “Communists,” offending other government officials enough to prevent him from ever receiving another airmail contract.

Relations between Cord and O.R., who had initially admired each other, deteriorated. O.R. questioned Cord’s treatment of the Century pilots, the Auburn factory workers and the Auburn dealers. Cord forced dealers to stock impractical, poorly selling models and balked at providing repairs when those cars developed mechanical problems.

1932: IT WAS A VERY BAD YEAR

For O.R., 1932 was a far cry from the good times of 1929. On January 29, a Century Pacific airplane crashed in the mountains south of Bakersfield, killing all aboard. Because of bad weather and rough terrain, five days passed before the victims were found. Although Motor Transit buses had been involved in the occasional accident, nothing as serious as this had ever happened while O.R. owned the bus company.

In May, O.R. received a letter threatening him with death unless he provided $50,000. O.R. promptly turned the letter over to the police. Detectives determined that it was O.R.’s former chauffeur, recently terminated from employment, who had sent the letter. The ex-employee was quickly arrested.

By mid-year, Century Pacific Airlines had gone out of business, and Auburn-Fuller went into receivership. Much of O.R.’s wealth was in stocks, which were by now nearly worthless. He did not bother to attend the Century Pacific dissolution hearing on July 13, where Cord and his lawyers tried to prevent O.R. from taking his share of airline stock.

At year’s end, O.R. decided to retire from the business world, leave Los Feliz and live on his ranch near Corona. However, this would not be a leisurely retirement; there would be much hard work to be done on the ranch so it could financially support his family.

BACK TO THE RANCH

O.R.’s Eastvale ranch, three thousand acres six miles north of Corona, had been in the family since the 1870s. The Fuller brothers raised horses for Pioneer Truck and Transfer. As motor trucks replaced horse-drawn wagons, Charles Fuller gave less and less attention to the ranch, finally passing it on to O.R. in 1925.

O.R. expanded the ranch by purchasing adjacent property until it grew to five thousand acres. He leased an additional two thousand acres near the Santa Ana River, making it the largest ranch in the area.

The Fuller family enjoyed spending weekends at the ranch. In 1927, they built an elaborate ranch house, named Casa Orone (combining O.R. and Ione). It was lavishly appointed with Italian woodcarvings, Spanish rugs and other fine furnishings. And now it was going to be their permanent home, far away from the glamour of Los Feliz.

O.R., remembering his boyhood on that Kansas farm, started a dairy and a poultry farm. Within a few years, the Fuller Rancho had become the largest turkey farm in Southern California. Fuller Rancho trucks delivered milk and eggs all over Southern California. O.R. opened the Fuller Rancho Market, a drive-up grocery store, in Pomona.

For additional income, the Fullers opened Casa Orone as a guest ranch in 1937. Rooms were added to the house until there was space for twenty-five guests.

The Fuller Guest Rancho offered horseback riding, boating in the river, swimming pools, a fine restaurant and a comfortable lounge. There was also illegal gambling, with card tables and slot machines designed to be quickly hidden if law enforcement agents came calling. O.R. himself loved to gamble and often spent many hours playing poker.

Life at the Guest Rancho seemed like one big party lasting for days. Celebrities such as W.C. Fields, Groucho Marx, Spencer Tracy and Red Skelton were frequent guests. The Guest Rancho hosted many weddings, luncheons and business meetings.

In 1938, O.R. subdivided the ranch and sold lots with river views. One of the first purchasers was actor Charles Grapewin, who claimed to have won it from O.R. in a poker game. The street near his former property is still named Grapewin Street.

During World War II, medical staff and patients from the nearby Naval Hospital (Norconian Hotel) visited the Guest Rancho for relaxation, while German prisoners of war worked the fields.

O.R. passed away in 1946, and the Guest Rancho closed one year later. Ione remarried and continued living at the ranch until her death in 1951. Shortly thereafter, the ranch was purchased by a local dairyman. Casa Orone became a senior citizens residence and then was used as a home for wayward youth until it was demolished in 2004. Most of O.R.’s Eastvale ranch is now suburbia, covered with tract homes and shopping centers, although a few dairy farms still operate. In June 2010, residents voted to make Eastvale an incorporated city.

EPILOGUE

By 1939, the name Motor Transit had disappeared from the buses, and the routes were simply known as Pacific Electric. The basic structure of Motor Transit’s bus route network remained intact through the decades as Metropolitan Coach Lines, Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority, Southern California Rapid Transit District and Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA or “Metro”) operated the buses. Some routes changed as Southern California’s freeways opened, and longer routes used them to speed service. In the mid-’70s, the outlying counties (Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino) formed their own transit agencies and took over the portions of bus routes in their jurisdictions; Foothill Transit did the same for eastern Los Angeles County in the late 1980s.

Although the automobile business is usually assumed to be hostile to public transit, other automobile entrepreneurs have unwittingly followed O.R.’s lead in providing public transportation. J. Chapman Morris, a Chevrolet dealer in Fillmore, California, founded Fillmore Area Transit Corporation (FATCO) in 1973. FATCO provides local service in and around the city of Fillmore to this day. More recently, Yosuf Maiwandi, a Monrovia-based auto mechanic, implemented the San Gabriel Valley Transit Authority, offering free rides to the elderly and disabled, in the early 2000s.