CHAPTER 6

BRUNNER, RINDGE, HOYME AND HENDLER

Transportation Pioneers of the Malibu

The scenic Pacific Coast Highway (PCH) provides an enjoyable drive—when it is not congested—along the Malibu coast between Santa Monica and Oxnard. However, few who travel PCH know the long and complicated history of the road. Even fewer know about the attempts to provide public transportation along the highway.

Fredrick and May Rindge, who owned the land comprising Malibu, fought vigorously against the highway crossing their property in the early twentieth century. Once the Rindges lost their battle and the road opened to the public in 1929, entrepreneurs such as Francis Brunner, Major Robert Hoyme and Frank Hendler attempted, with varying success, to provide bus service along PCH.

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S PRETTIEST DRIVE

Francis Brunner, the son of Rudolf Brunner and Clara Schroff Brunner, was born on December 17, 1899, in Santa Monica. In his late teens, he worked as a copy reader for the Los Angeles Examiner. He left Santa Monica in 1919 to attend Pomona College and the University of Michigan. He returned to Santa Monica in 1923 and worked at the Los Angeles Herald as a copy editor.

Southern California’s “Prettiest Drive” schedule pamphlet. Courtesy Topanga Historical Society.

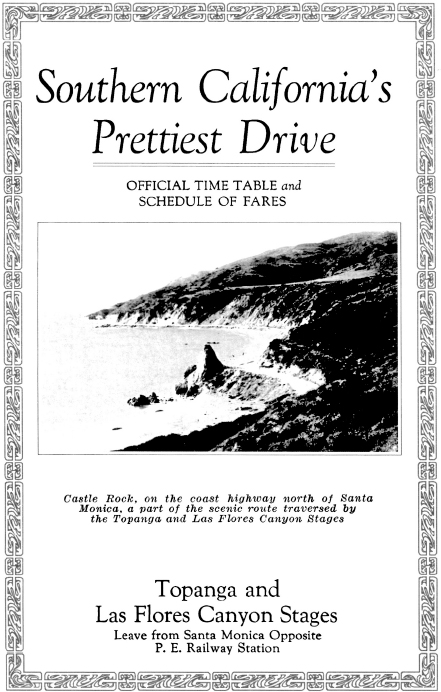

Topanga and Las Flores Canyon Stages, 1925. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

In November 1924, Brunner purchased the Topanga and Las Flores Canyon Stages bus line from Topanga Canyon pioneer Thomas Cheney for $1,200. All trips originated at the Santa Monica Pacific Electric station; three daily round trips went to Topanga Canyon and two to Las Flores Canyon.

Brunner marketed the bus line as “Southern California’s Prettiest Drive.” Although the bus line was primarily intended for sightseeing, Brunner sold one-way fares for those people staying at one of the numerous inns or campgrounds along the routes. A trip through the canyons, Brunner said, could improve one’s appetite, relax the nerves and cure the “blues.” Onboard the Stages, Brunner intoned, “the only ‘blues’ are the blues of rollicking ocean waves, the blues of clearest skies, and the blues of range on range of distant mountains.”

The first “buses” on the Las Flores and Topanga routes were Dodge and Packard automobiles, “stretched” to accommodate more passengers. In 1926, Brunner bought a Graham Brothers coach, primarily to carry schoolchildren from Topanga Canyon to Santa Monica, but it was also used on his regular routes.

Brunner operated tours to the Topanga Summit, which provided an expansive view of the San Fernando Valley. Another tour traveled the coast road past Las Flores Canyon and through the Malibu Ranch. He anticipated the construction of a public highway through the ranch. Like many of his passengers, he wondered, “What lies over the hill beyond the end of the paved road?”

THROUGH THE MALIBU RANCH

This piece of paradise, known as the Malibu Ranch (or Rancho Topanga Malibu Sequit), was mostly off limits to the general public. Malibu, named after the Chumash word for “loud surf,” was originally granted by the Spanish government to Jose Bartolome Tapia in 1805. The ranch passed through several hands before Fredrick and May Rindge of Boston bought it in 1892.

Fredrick and May loved their ranch. In 1898, Fredrick wrote a book, Happy Days in Southern California, extolling the virtues of the Malibu Ranch, comparing it to the Italian Rivera and proposing a road for leisure trips in horse-drawn carriages.

The Rindges permitted a few tenants to live on the ranch. Otherwise, public access was severely restricted. The main road through the ranch remained closed; tenants and other travelers had to use a path along the beach. During high tides, the path was impassable, and those traveling to and from their homes often had to wait several hours until the ocean receded.

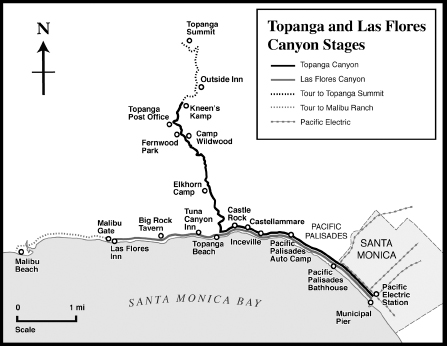

In the late 1890s, the Southern Pacific Railway planned to extend its line from Santa Monica to Oxnard through the Malibu Ranch. Fredrick Rindge did not want Southern Pacific “invading” his land, and he knew that if there were already a railroad on the ranch, Southern Pacific would be less likely to apply eminent domain condemnation proceedings. In 1903, he formed the Hueneme, Malibu and Port Los Angeles Railway Company and began construction on the Malibu Ranch’s own rail line.

The sudden death of Fredrick in 1905 changed nothing. May continued to keep the public out and worked to prevent a public highway from being built through the ranch. Armed men on horseback met trespassers and shooed them off the property. Her strong insistence that the public stay off her ranch, and her even stronger actions to keep people away, earned her the title “Queen of the Malibu.”

Hueneme, Malibu and Port Los Angeles Railway. Adapted from David F. Myrick, “The Determined Mrs. Rindge and Her Legendary Railroad,” Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly 41, no. 3/Mapcraft.

May took charge of the Hueneme, Malibu and Port Los Angeles, making her one of the few women in history to own a railroad. By 1908, she had built about fifteen miles of railroad along the shore between Las Flores Canyon and Encinal Canyon, passing via Point Dume. It mostly carried agricultural products and supplies to and from the pier. On rare occasions, it carried ranch visitors. However, the railroad was never extended off the ranch; doing so would require negotiating with the Southern Pacific on the east end. Extending tracks west to Oxnard involved cooperation with the Broome family, who guarded their ranch as jealously, if not more so, than the Rindges did theirs.

Rindge used legal and extralegal means to keep interlopers, including County of Los Angeles officials, off the ranch. In courtroom hearings, Rindge testified that settlers and trespassers harassed her family, started fires and stole cattle. The courts sided with the county, but when road builders started work, they were met by men with guns. Once, Rindge had parts of the road near the gates blown up with dynamite.

The legal battle went to the United States Supreme Court in 1923. In the case Rindge Company v. Los Angeles County, the court affirmed the county’s right to use eminent domain to build a public road through the ranch.

The State of California proceeded to condemn a right-of-way through the ranch for a highway in 1927. Much of the right-of-way was formerly that of the railroad, which had been damaged by storms in 1914 and 1916. On June 29, 1929, PCH, then known as the Roosevelt Highway, opened to the public. Governor Clement C. Young cut a ceremonial ribbon across the road, and traffic started flowing through the formerly “forbidden” property.

Because her legal battles nearly bankrupted her, Rindge decided to start subdividing her ranch. A few small lots became the Malibu Colony, which attracted movie stars in search of privacy. May Rindge passed away on March 12, 1941, in Los Angeles, away from her beloved Malibu Ranch. As for the Malibu railroad, nearly all of the track had been taken up and sold for scrap by the mid-1930s. However, forgotten pieces of rail have occasionally popped up out of the pavement as recently as the mid-1970s.

BRUNNER GOES TO OXNARD

Before the Coast Road even opened, bus companies big and small began planning to use it. The new road would shorten trips between Santa Monica and Oxnard, Ventura, Santa Barbara and San Francisco. No longer would passengers have to ride Pacific Electric into downtown Los Angeles and then transfer to a northbound train or bus. Instead, they could enjoy a shorter and more scenic ride along the coast.

Brunner saw the new road as his second opportunity to expand service. In 1926, he had filed an application with the California Railroad Commission for a certificate to run a bus service between downtown Los Angeles and Pacific Palisades via Beverly Boulevard. However, both Pacific Electric and the City of Los Angeles, thinking that Brunner lacked sufficient financial support to run the line, convinced him to transfer the certificate to Pacific Electric.

Brunner turned his full attention to obtaining a certificate to operate along the coast road. He formed a corporation called Santa Monica Mountain Coach Line to operate both his existing routes and the new service. The Mountain Coach Line, using Studebaker buses, would run up to eight round trips every day between Santa Monica and Oxnard, making local stops along the way.

Four other companies proposed service via the new road. Southern Pacific’s Pacific Coast Motor Coach Company proposed two round trips between Santa Monica and Oxnard. Pickwick Stages, the big statewide bus company, sought to extend its route from San Pedro to Oxnard, via Santa Monica. Another bus operator, confusingly named Motor Coach Company and headquartered in Lomita, planned to extend its Long Beach–Santa Monica route to San Francisco. Finally, Los Angeles and Oxnard Daily Express, a trucking firm, expressed interest in operating a bus linking Los Angeles, Santa Monica and Oxnard but failed to apply for a certificate from the Railroad Commission.

About a month before the road opened to the public, Brunner obtained permission from the California Highway Commission for a test drive. Studebaker supplied a luxurious, late-model parlor coach for the demonstration. On May 2, 1929, the bus arrived in Santa Monica at 10:00 a.m. Brunner—along with Santa Monica mayor Herman Michel, Studebaker representatives, other prominent citizens and the press—boarded the bus. At 10:30 a.m., the coach left Santa Monica and headed onto the coast highway for the trip to Oxnard.

Passengers relaxed in the comfortable seats and watched the scenery go by as the bus sped past Malibu Beach at up to seventy miles per hour. The road was in excellent condition, save for a few small landslides near Point Mugu. At 11:40 a.m., the bus arrived in Oxnard, where members of the local chamber of commerce greeted the travelers. Shortly thereafter, the bus continued on to Ventura, where it was met by city officials.

After a day of touring Ventura and Oxnard, Brunner and the others attended a meeting of the Oxnard Chamber of Commerce. He made a presentation promoting his proposed bus line, comparing it with the Pacific Coast Motor Coach Line’s competing proposal. Southern Pacific planned to use these buses to connect passengers from Santa Monica to its trains in Oxnard.

“The S.P. plan is doomed to fail,” declared Brunner. “Their buses will only go to Oxnard with but two trips a day. There is not enough revenue in that and it does not develop business. Besides, bus passengers do not travel on trains, or vice versa, so the S.P. plan of having Oxnard as a transfer point will never work.”

Norman Robotman, a representative of the Pacific Coast Motor Coach Company, took notice as Brunner continued to describe his proposed Mountain Coach service. Upon questioning by Robotman, Brunner admitted that his Las Flores Canyon route was a money loser and that Santa Monica Mountain Coach was extremely underfunded, with only $700 in the bank.

After the meeting, Brunner and the others returned to Santa Monica via the Conejo Grade, Ventura Boulevard and Los Angeles.

HEARINGS AND REHEARINGS

At a series of Railroad Commission hearings in July 1929, representatives of Brunner’s Santa Monica Mountain Coach, Pickwick Stages, Pacific Coast Motor Coach and the Lomita-based Motor Coach Company testified as to why the company they represented was most qualified to provide the Santa Monica–Oxnard route.

Because Brunner had no experience beyond the Topanga and Las Flores Canyon routes, the Commission was not confident in his ability to operate a more extensive service. Instead, the Commission awarded the certificates to the Motor Coach Company for service to San Francisco and to Pacific Coast Motor Coach for local service between Santa Monica and Oxnard.

However, the United States long-distance bus industry had been consolidating throughout 1929; smaller companies merged or were acquired by larger firms. In California, Southern Pacific’s bus operations merged with Pickwick Stages to form Pacific Transportation Securities, which would eventually become Pacific Greyhound Lines.

In light of the changes in the bus industry, the Commission agreed to rehear the issue of Malibu bus service on December 3, 1929. This time, only Brunner’s Santa Monica Mountain Coach, Pickwick and Motor Coach Company applied. Again, the hearings and testimony continued over several days. Pickwick representatives stated that the company planned to spend $1.25 million on one hundred new buses and that it was the most qualified of the four applicants to operate the Coast Highway service. This time, the Commission awarded the certificate for operations over the Coast Highway to Pickwick, again shutting Brunner out.

BRUNNER’S LAST STAND: BUSES TO THE PALISADES

The Pacific Land Company, which developed and sold land in the Pacific Palisades, had provided bus service between Santa Monica and the Palisades since the early 1920s. Originally intended to encourage purchase of real estate, the service was poorly patronized, and the company planned to cancel it.

Brunner bought the bus line in 1933, hoping that it would become profitable. Unfortunately, neither the Palisades route nor his service to Topanga and Las Flores Canyons made any money. Also, the schools had chosen another bus company to transport their students. Brunner needed a more stable source of income, as he had recently married and started a family.

In June 1935, Brunner sold all of his bus operations to the City of Santa Monica. The Santa Monica Municipal Bus Lines incorporated the Palisades route into its network but refused to continue service on the lightly used Las Flores and Topanga Canyon routes.

After Santa Monica acquired his bus line, Brunner sought employment as a bus driver. Instead, the city hired him to create a bus tour program. Brunner developed several guided tours to places such as the Los Angeles County Fair, Lake Arrowhead and the 1935 World’s Fair in San Diego. By 1940, Santa Monica’s bus tours were traveling as far as Arizona’s Grand Canyon and Oregon’s Crater Lake.

In 1941, Brunner became director of special tours for the Tanner Gray Line, a sightseeing bus company. The position was short-lived, however, as the United States’ entry into World War II quickly put an end to luxuries such as guided bus tours. He entered the aircraft industry, eventually ending up at Hughes Aircraft, until he retired in the mid-1960s.

In his later years, Brunner, along with his wife, Barbara, helped develop a bus service bringing concertgoers to the Hollywood Bowl from various parts of Los Angeles County. Brunner, with the encouragement of his son, Robert F. Brunner, a composer with Walt Disney Studios, composed a Christmas song (“Here He Comes, Santa Claus”). Brunner died on September 18, 1981.

MAJOR HOYME’S SHORELINE TRANSIT

After World War II, the population of Malibu nearly tripled. Residents requested local bus service along Pacific Coast Highway to Santa Monica, as Greyhound’s schedules were designed for long-distance travelers. The Malibu post of the American Legion began advocating for local bus service. One member, Major Robert Hoyme, was vice-president of Mack Truck’s bus division.

Christopher Robert Hoyme was born on April 11, 1888, to Reverend Gjermund and Ida Hoyme in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. In the early 1910s, he worked as a sales manager at several early automobile manufacturers, including Autocar, International Motor and Alco.

During World War I, he served in the American Expeditionary Forces in France, rising to the rank of major. After the war, Major Hoyme worked as a Madison Avenue advertising executive and then traveled to Egypt in 1922 to accompany Lord Carnavon and Howard Carter on their exploration of King Tutankhamun’s tomb. After returning to the United States, Major Hoyme became manager of Mack Truck’s bus division in Chicago. The company transferred him to its Los Angeles office in 1942.

Hoyme applied to the California Public Utilities Commission for the necessary certificate. Greyhound did not protest Hoyme’s application, clearing the way for the local bus service.

Hoyme’s bus line, dubbed “Shoreline Transit,” started on August 17, 1946. Among the celebrities attending the opening ceremony were comedian Ole Olsen and actor (and unofficial Malibu “mayor”) Wayne Baxter. Santa Monica mayor Ray Schafer, along with Baxter, cut a ribbon across Pacific Coast Highway, and the first bus rolled into service.

Shoreline Transit operated two routes: Santa Monica–Malibu and Santa Monica–Topanga Canyon. The company had a nautical theme. Hoyme called the buses “Shoreliners”; the drivers, sporting blue sailors’ uniforms, were referred to as “skippers.” The buses even had racks for fishing poles. On Sundays, special runs from Santa Monica connected with the Lenbrook and Gee Bee fishing boats.

Unfortunately, low ridership and mechanical problems bedeviled Shoreline Transit. The company canceled the Topanga Canyon route in 1947 and suspended operations during the winter in 1950. After Major Hoyme died on October 20, 1950, Henry Turcotte and Harold Van Wagner, two Shoreline Transit skippers, acquired the company in February 1951. Shoreline Transit continued to lose money. About 350 daily fares were needed to break even, but the buses carried only about 100 passengers each day. On December 23, 1952, the buses, festooned with banners announcing, “We did the best we could,” made their final runs. The demise of Shoreline Transit left Malibu without local public transportation until 1973.

Shoreline Transit opening festivities. From left to right: Actor Leo Carillo, Santa Monica mayor Ray Schafer and Malibu “mayor” Warner Baxter. Courtesy Malibu Lagoon Museum.

FRANK HENDLER’S “THE BUS”

Frank Hendler was born on February 12, 1929, and grew up in West Los Angeles, attending Hamilton High School and UCLA. By the mid-1960s, he had become an architect and moved to Malibu, where he designed several luxury houses. In 1970, he became the director of the Malibu Community Coordinating Committee, a citizens group designed to call attention to tasks it felt the County of Los Angeles was not performing well, as well as to give Malibu a sense of community.

Malibu residents again started requesting bus service along PCH. People were spending a lot of time driving their children to and from the beach, school and other activities. Traffic speeds and the lack of sidewalks made walking or biking dangerous. Buses would also give visitors an alternative to driving to the beach, reducing the number of cars on PCH and the need for beachfront parking.

Although a local bar owner collected one thousand signatures on a petition requesting Santa Monica Municipal Bus Lines to extend service from Santa Monica to Malibu, Jack Hutchinson, the bus line’s director, expressed skepticism about ridership. He was also concerned that the frequent traffic jams on PCH would make it difficult to keep the buses on schedule.

Santa Monica’s lack of interest only made the Committee more determined to provide bus service. Under the direction of Hendler, the Committee contracted with a local charter bus company to serve PCH between Santa Monica and Malibu. The buses were equipped with tape players and could carry surfboards, fishing poles and other beach gear.

The Malibu Recreational Transit System, or “The Bus,” made its first run on June 16, 1973. One route ran from the Malibu Civic Center to Santa Monica and the other from the Civic Center to Trancas Beach. An all-day ticket cost fifty cents. Young people headed to the beach made up most of the riders; senior citizens also enjoyed the mobility provided by the new line. “The Bus” carried between 350 and 450 riders each weekday and 250 on Saturdays. No service operated on Sunday.

Hendler’s new bus service raised eyebrows at the California Public Utilities Commission when officials found out that he had started the service without applying for the required certificate. Upon notification, Hendler quickly submitted the proper forms, and the buses kept rolling.

In order to break even, 2,600 passengers per week would have to ride. Since weekly ridership was only 2,000, Hendler expected community donations to make up the shortfall. But many pledged donations were never received. Hendler paid the difference out of his own pocket and warned that the service would shut down if the money never came in.

“People told us they would donate to us tomorrow,” he said. “Well, tomorrow is here and there’s not enough money left to run the bus today.” Hendler vowed to keep the service running until the Southern California Rapid Transit District (RTD) started its Valley–Santa Monica bus later that summer, hoping that RTD passengers arriving in Santa Monica would boost ridership by transferring to “The Bus.”

After service ended for the season on September 7, Hendler discovered that “The Bus” had nearly broken even. Encouraged by several phone calls urging him to keep the buses running, Hendler announced plans to restart the service next year, continue operating it throughout the year and add routes to UCLA and Pepperdine University, which had moved to Malibu in 1972. He negotiated with the Santa Monica Municipal Bus Lines to provide a bus at a reduced rate.

Hendler applied to the Urban Mass Transportation Administration to obtain federal funding for his bus system. But UMTA focused on helping big-city transit systems. After being turned down by the agency, Hendler proposed a “community transportation improvement district” that would tax Malibu residents to provide funding for the bus system.

Although Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley expressed a mild interest in Hendler’s community bus system, officials of the County of Los Angeles were more interested in extending RTD bus service to Malibu. The county had subsidized an RTD shuttle bus along the coast between Malibu and Manhattan Beach during the same summer Hendler was operating “The Bus.”

In May 1974, the county approved RTD Line #175 between Santa Monica and Trancas Canyon on a six-month trial. Unlike “The Bus,” RTD had no provision for carrying bikes or surfboards. After the trial, Hendler, with Hutchinson now in agreement, asked that the Santa Monica Municipal Bus Lines be allowed to take over the Malibu route, as its costs were lower than those of RTD. But the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors wanted RTD to run the bus route, and RTD insisted on keeping it. RTD (and its successor, Metro) has operated bus service along Pacific Coast Highway to the present date.

PARKS AND POLITICS

In addition to his community-organizing activities, Hendler was a vocal proponent of preserving open space in the Santa Monica Mountains. “You can’t compare these mountains with Big Sur or Yosemite,” he said. “But they’re the best we have, and there are 10 million people living in the Los Angeles area. Those mountains are a very beautiful thing, but you have to feel that by hiking right into them,” he said. After the National Park Service formed the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area in 1978, Hendler joined the Santa Monica Mountains Trails Council and continued to advocate for improving the park.

Hendler was also in favor of cityhood for Malibu. During the spring of 1976, he campaigned in favor of a cityhood ballot measure and ran for one of the city council seats that would be available if cityhood were approved. When the bid failed, Hendler, along with the four other candidates receiving the most votes, formed a “Cityless Council.”

After a few years in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Hendler moved to Pietra Santa, Italy. There, he designed two identical marble sculptures, named The Peacemakers, commemorating the historic December 7, 1987 meeting between U.S. president Ronald Reagan and Soviet general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev. Sadly, he did not live to see the final placement of The Peacemakers, as he passed away on October 15, 1989. In the early 1990s, the artworks were installed at Shenandoah University in Virginia and at the Federation of Peace and Conciliation in Moscow.

EPILOGUE

Frank Hendler’s dream came true on March 28, 1991, when Malibu became an incorporated city. The days of the gates and the armed riders guarding the Rindges’ ranch were seemingly over. However, Malibu remains somewhat isolated, both socially and geographically. Other than PCH, road access is limited to several winding mountain roads.

In Malibu, the average home costs in the tens of millions of dollars. Residents, many of whom are celebrities or business moguls, have made it difficult for the general public to access beaches near their properties, even though the beach below the mean high tide line is legally available to all. The Colony remains a very exclusive neighborhood in Malibu, inhabited by today’s stars and gated for privacy.

Most people who can afford to live in Malibu do not ride the bus. Metro Route #534 transports mostly domestic employees and a few beachgoers from Greater Los Angeles. After about seventy-five years of service, Greyhound discontinued its route through Malibu in April 2005 because of low ridership.

While Metro’s #534 and a Los Angeles County summer-only “Beach Bus” through Topanga Canyon are not the modern-day descendants of Francis Brunner’s Topanga and Las Flores Canyon Stages, these bus routes allow anyone to enjoy a trip along the coast, seeing it as Brunner saw it, where the only “blues” are “blues of rollicking ocean waves, the blues of clearest skies, and the blues of range on range of distant mountains.”