CHAPTER 8

THE SCHOOL BUS SCANDAL

The Landiers

The Landiers of San Pedro were another family who influenced Southern California’s transportation history. Felicien Landier, along with his two sons, Felicien Paul (“F.P.”) and Robert, turned a group of undisciplined jitney drivers into the San Pedro Motor Bus Company. F.P. also improved bus service in Watts and, during the 1940s and ’50s, operated a large fleet of buses for the Los Angeles City Schools. However, a California Grand Jury investigation of the school system unearthed a conflict of interest scandal that not only put F.P. out of the school bus business but also laid bare his convoluted marital life.

NEW ORLEANS

Felicien Landier, the son of French immigrants Julien and Felicite Landier, was born in New Orleans on June 14, 1879. When Felicien was a young child, the family returned to France. He attended school in Paris and excelled in music. The Landiers returned to New Orleans in 1887, and Felicien, as he grew older, played in the New Orleans orchestra.

LA BOURGOGNE AND THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR

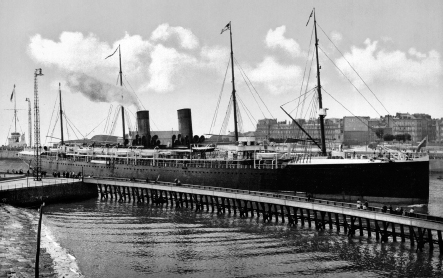

The Landiers, either separately or together, traveled back and forth between France and the United States on the fast steamships of the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, or French Line. These ships crossed the Atlantic in seven days. However, the French Line was often accused of operating its ships recklessly.

On July 3, 1898, Julien boarded the French ship La Bourgogne in New York for a trip to France. As the ship traversed the North Atlantic, it encountered a heavy fog. In the early morning of July 4, La Bourgogne collided with an English ship, Cromartyshire, near Cape Sable, Nova Scotia.

The scene aboard the French ship was one of chaos and desperation. Crew members used fists and knives to push passengers out of lifeboats to save themselves. Although nearly half of the 220 crew members were saved, just 70 of the 506 passengers survived, including only one woman and no children. Julien, a third-class passenger, did not survive.

At the time La Bourgogne sank, Felicite and two other children were in France and decided to remain there. Felicien enlisted with the Naval Reserves and served as a bugler in the Spanish-American War.

La Bourgogne at Le Havre, France. Photochrom Prints Collection, Library of Congress.

In December 1898, Felicien married Alice Delormel. Over the next eight years, Felicien and Alice had four children, including Felicien Paul (“F.P.”) and Robert.

SAN PEDRO MOTOR BUS ASSOCIATION

In 1909, the Landiers moved to Los Angeles, where Felicien found work as a bandleader, a laundryman and a jitney driver. The Landiers settled in San Pedro in 1915. Felicien started several businesses, including a bowling alley (he was an avid bowler), a candy shop and a soft drink bottling company. He also served as an agent for the French ships calling at San Pedro. Felicien was extremely civic-minded; one of his projects was developing the land at Point Fermin into a public park.

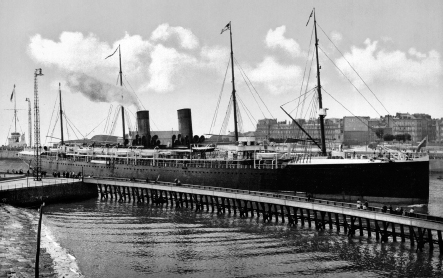

Along with Pacific Electric’s local streetcars, jitney buses, predominately driven by Italian immigrants, provided public transportation in San Pedro. Seventh Street and Harbor Avenue was the “hub,” where buses departed and returned. The Landiers managed two routes: one to Point Fermin and another to White Point. Other routes in San Pedro were “owned” by individual families. The Bono family operated the Barton Hill bus route, while the La Rambla neighborhood was covered by the La Pinta family.

Drawing on his experience as a jitney driver, Felicien organized the drivers into the San Pedro Motor Bus Association. Drivers joined by providing a bus and agreeing to follow established routes, maintain schedules and operate in an orderly fashion. Managing all of these independent drivers was not easy. Each driver was out for himself, and drivers cutting in front of one another in competition for fares was common. Arguments and even fistfights between drivers happened often. Felicien would request that the Los Angeles Board of Public Utilities and Transportation revoke the permit of a particularly disagreeable or insubordinate driver.

F.P. and his younger brother, Robert, entered the bus business as soon as they were old enough. F.P. became a driver and a mechanic, while Robert, who also owned an insurance agency, managed two of the San Pedro bus lines.

During the Great Depression and into World War II, the buses were profitable, as relatively few San Pedrans owned automobiles. Employees of the tuna canneries on Terminal Island rode the bus to the ferry terminal and then boarded the ferry to their jobs. Soldiers and sailors from Fort MacArthur and the Pacific Fleet were frequent bus users. The buses were so popular that Pacific Electric abandoned its local San Pedro streetcars in 1938, leaving only the interurbans to Los Angeles and Long Beach. In 1943, the association became the San Pedro Motor Bus Corporation.

San Pedro Bus System. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

Robert continued managing the bus system until 1971. Faced with aging buses, rising labor and insurance costs and increased use of private automobiles, the bus company went out of business, and the Southern California Rapid Transit District (RTD) took over the routes.

THE LANDIERS TAKE OVER BUSES IN WATTS

In the early 1920s, Felicien and F.P. decided to expand their transportation business to other parts of Southern California. In 1926, they turned their attention to Watts, a small city that became a part of Los Angeles on May 28.

Watts, originally a small agricultural settlement near a Pacific Electric railway junction, became an incorporated city in 1907. The first African Americans to settle in Watts were railway workers. More arrived from the South during World War I seeking employment and a better life. A substantial Mexican American population lived there too. Most businesses in Watts, however, were owned or controlled by whites.

Local entrepreneurs used horse-drawn carriages to take people to and from the Pacific Electric stations in and near Watts. In the 1910s, they started using automobiles, and then small buses, for this purpose. It was easy to get a bus franchise in Watts; often a hastily scrawled note to the city trustees was all that was necessary. By the early 1920s, an informal network of owner-operator driven routes had developed.

After annexation, officials from Los Angeles’s BPU&T sent an inspector to Watts to investigate the bus services. The inspector’s report described buses operating on irregular schedules, drivers failing to complete trips and bus runs canceled if a more profitable charter bus request came along. When the BPU&T tried to enforce minimum standards in 1927, there was much opposition. One driver had his permit revoked for making death threats against the inspector. Certain other drivers offered to sell their permits and vehicles.

The Landiers began acquiring the permits of the independent operators and consolidating the routes under a single company. Because most bus owner-operators were African American, members of the black community, led by Walter R. Knox, protested the Landier takeover. Knox accused the BPU&T and the chamber of commerce of driving the owner-operators out of business and giving the permits to the white Landiers. BPU&T officials tried to assure the community that its decision was based on service quality, not on race. However, Knox, along with other black citizens in Watts, remained unconvinced.

F.P. Landier. Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

General Motors school bus advertisement. Author’s collection.

By October 1928, the Landiers, operating as L&L Transportation Company, had acquired all local bus services in and around Watts. In 1936, F.P. bought out his father’s interest in L&L and formed a partnership with William C. Kemble. The new company operated transit and school buses under the name Landier and Kemble. After two years, Kemble sold his share of the business to F.P., who then formed a new company, Landier Transit.

GARDENA AND TORRANCE

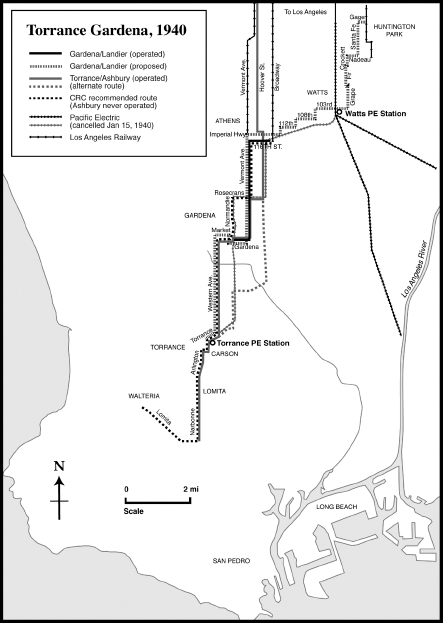

In 1939, Pacific Electric, facing financial difficulties, announced the cancelation of several routes, including the route serving Gardena and Torrance. PE planned to replace several rail lines with buses, but not the Gardena–Torrance route, leaving the two cities to develop their own bus service.

The last PE train clattered through Gardena during the night of January 14, 1940. The next morning, Landier Transit buses, under contract to Gardena, operated along a route connecting the city with Los Angeles Railway’s streetcar terminal at Vermont Avenue and 116th Street. Simultaneously, the City of Torrance started a bus line that provided direct, no-transfer-needed service to downtown Los Angeles. Asbury Rapid Transit System, which primarily served the San Fernando Valley, operated the Torrance–Los Angeles bus route.

Officials of both Gardena and Torrance hoped that either Landier or Asbury would operate the bus service as a profit-making concern. Landier proposed a route serving Torrance, Gardena, Watts and Huntington Park. Passengers going to Los Angeles could transfer to either the Los Angeles Railway streetcar or the Pacific Electric. The proposed Asbury route would connect Walteria, Lomita, Torrance, Gardena and downtown Los Angeles.

Because the Railroad Commission was unlikely to approve both routes, each company, with its respective city behind it, promoted its route as the best choice. The debate between the two proposals raged in both city councils and in the press. The Torrance Herald supported the Asbury plan, while the Gardena Valley News endorsed Landier’s offering.

Torrance and Gardena proposals. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

Torrance mayor William H. Tolson, on discussing the Landier route, said, “We don’t want anything to do with that kind of a deal. In the first place, our residents want transportation to and from Los Angeles, not Huntington Park or Watts. In the second place, such a deal would deprive Walteria and Lomita residents of through bus service they now enjoy with the Torrance municipal buses.”

Los Angeles’s BPU&T opposed the Asbury route because the company planned to allow local passengers to ride between Imperial Highway and downtown Los Angeles, taking business away from the streetcars.

On June 18, 1940, the Commission rejected the Landier proposal and granted Asbury a certificate to provide bus service from Torrance and Gardena to the 116th Street/Vermont streetcar terminal. No service to downtown Los Angeles or Walteria would be provided. Unhappy with the Commission’s decision, the two cities decided to continue operating their municipal buses. Torrance Transit and Gardena Municipal Bus Lines have operated ever since.

F.P. still insisted that a bus to Huntington Park was necessary because of industrial growth in South Los Angeles. He applied again to the Commission. New commissioners had been appointed in the interim, and this time, the certificate was granted. On November 27, 1941, the first Landier Transit buses rolled along Pacific Boulevard in the heart of Huntington Park’s shopping district.

LANDIER TRANSIT IN WARTIME

F.P. anticipated increased ridership on the Huntington Park route during the Christmas shopping season. However, the events of December 7, 1941, quickly changed everyone’s priorities.

Public transportation companies across Southern California, from the vast Pacific Electric to the tiny, three-bus Victory Transit Company in Pomona, added as much service as possible to accommodate soldiers going to the battlefronts and war workers commuting to shipyards and aircraft plants. Gasoline and tires were rationed, motivating many to carpool or use public transportation.

Landier Transit added several bus routes to the shipyards on Terminal Island. Unfortunately, ridership was disappointingly low. Shipyard workers received a larger gasoline ration than ordinary commuters, encouraging them to drive to work. After a few weeks, Landier Transit discontinued the special wartime routes.

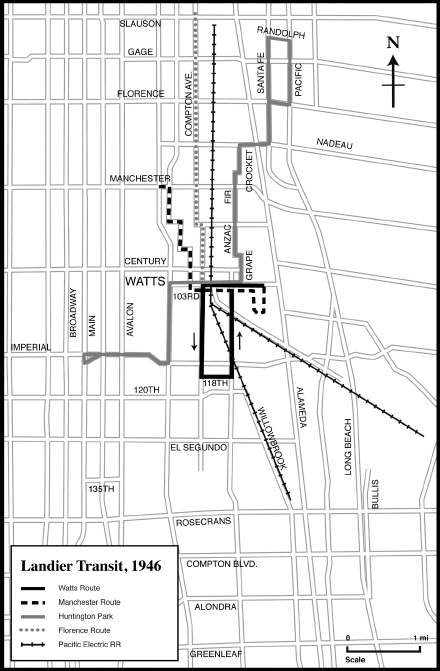

TROUBLE IN WATTS

In addition to his school and transit bus service, F.P. offered special bus routes to the Santa Anita and Hollywood Park horse racing tracks. Landier Transit acquired a certificate in 1946 to carry youth groups to Big Pines in the San Bernardino Mountains. But the groups soon decided to make other transportation arrangements, so the Big Pines route lasted only a year.

Even though the population of Watts had ballooned during and after World War II, Landier Transit had not substantially increased the level of service on its local Watts bus routes since 1930. Since most Watts residents were transit-dependent, the Watts bus routes became overwhelmed. Passengers and community leaders complained bitterly about overcrowded buses, infrequent service, disrespectful and unsafe drivers and bus stops without shelters, exposing passengers to the weather.

In early 1947, a newly formed Watts Citizens’ Welfare Committee attempted to make Landier Transit aware of bus service deficiencies. On November 12, about five hundred people crowded into a BPU&T meeting. Landier Transit representatives were soundly booed when they attempted to defend the service provided.

The crowd was much more supportive of a bus system proposed by physician Dr. Simon Jaime and real estate agent Samuel Taylor, both African Americans and well regarded by the community. Their Watts Rapid Transit System had routes providing direct service to housing projects and other areas poorly served, or unserved, by Landier Transit. But what attracted the most attention was a drawing of a new terminal building for the Watts Rapid Transit buses. As the existing Pacific Electric station in Watts had fallen into disrepair, the citizens looked forward to a modern, up-to-date transit facility.

Since the proposed Watts Rapid Transit routes overlapped Landier Transit’s routes, Watts Rapid Transit would be prohibited, under Commission rules, from picking up and dropping off passengers along route segments also served by Landier Transit. Ben Rosenfeld, president of Landier Transit, said that Watts could not support two competing transit companies and predicted that both would go out of business if both companies were granted franchises.

Landier Transit Watts routes. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

The people of Watts rallied around Watts Rapid Transit. Their disdain for Landier Transit became worse after F.P. allegedly muttered a racial slur at a meeting. However, neither the BPU&T nor the Commission granted Watts Rapid Transit permission to operate, citing both competition issues and Jaime and Taylor’s lack of experience in the bus business. Instead, Landier Transit was allowed to continue operating, although F.P. was warned about having a “public be damned attitude” and being “perfectly willing to give the worst service that he can get away with in the Watts District.”

In response to these admonishments, F.P. improved the Watts service in 1948. Buses ran on time, and a new route on Compton Avenue, linking Watts and the Florence district, was added.

TROUBLE IN SCHOOL

By 1948, Landier Management Company, a separate division of Landier Transit, provided 95 percent of the routes serving the Los Angeles City Schools, using a fleet of two hundred buses.

In 1951, the Los Angeles County Grand Jury, hearing rumors about irregularities in hiring practices, began an investigation of the school system. Witnesses told of rigged examinations and discrimination against African American, Asian American, Jewish and middle-aged applicants.

At one grand jury hearing, school principal Ione Swan described dangerous playground equipment, tainted meat in cafeterias and financial improprieties. When the board asked her to provide evidence of her charges, she refused and was summarily dismissed.

Mrs. Swan’s accusations, however, caused the grand jury to review the school system’s business practices. It discovered that two board members, Roy A. Becker and Gertrude Rounsavelle, had clear conflicts of interest. Becker was an insurance broker who had written policies for Landier Transit since 1929. Gertrude Rounsavelle’s husband, Lafayette, was also an insurance broker. The two brokers, starting in 1947, both insured Landier, splitting the commission between them. Three years later, F.P.’s brother, Robert, through his insurance agency, started writing policies for the bus firm and receiving one-third of the commissions.

The grand jury was empowered to either indict or accuse Becker and Rounsavelle of violating state codes regarding conflict of interest. After being presented with the evidence, the jury could vote to convict. The consequences of conviction, if the jury chose indictment, was a $1,000 fine, five years in jail and a lifetime ban on holding public office in California. A conviction on an accusation meant that the only penalty would be removal from office for the current term.

Becker denied that he had done anything illegal, while Rounsavelle pleaded ignorance of her husband’s insurance business. Eleanor B. Allen, another board member, testified that she had seen Becker’s name on several insurance contracts.

On March 11, 1951, the grand jury voted to accuse both Becker and Rounsavelle of breaking the conflict of interest laws. Rounsavelle faced reelection on May 29. If she were convicted and reelected, she would have only been removed from office until her new term started in July. However, she lost the election and resigned a few days before her current term ended. Becker was put on trial, convicted and removed from office.

During Becker’s trial, the grand jury accused another board member, J. Paul Elliott, of conflict of interest violations. Elliott was an attorney who also worked for Landier Transit for a $200 per month retainer fee, and he had voted on the bus contracts at the same time. At his February 1952 trial, he claimed to be working for Landier Transit, which operated the Watts bus lines, rather than Landier Management, which handled the school buses. However, a review of the relationship between the two Landier companies showed that Landier Management had a controlling interest in Landier Transit. The checks Elliott received came from both companies. On March 7, he was convicted and removed from office.

WILL THE REAL MRS. LANDIER PLEASE STAND UP?

On October 12, 1951, the grand jury, continuing its investigations, indicted board member Olin Darby for similar activities. Darby had voted on contracts favoring a print shop and an ice cream plant, both of which were tenants on land he owned. The grand jury discovered, in the course of Darby’s hearing, that F.P. had invited, at his expense, several school board members and their spouses on two trips to Yosemite in 1948. As details about the trips came to light, board member Allen suddenly resigned.

While at Yosemite, F.P.’s guests thought that the woman accompanying him was his wife; everyone remembered calling her “Mrs. Landier.” But shortly after these trips were brought to public attention by the grand jury hearings, F.P.’s real wife, Honor B. Landier, announced that they had been legally separated since 1943. She then sued for divorce and an injunction preventing him from selling $1 million in marital assets. F.P. claimed that he and Honor had a “Mexican divorce” (a controversial ceremony in which both spouses need not be present) in 1935. By April 1952, the story of F.P. and his “wife” was all over the national press, even in Time magazine. The couple finalized their “American” (and legally binding) divorce in 1953.

VOIDING THE CONTRACT

Because board members with financial interests in the school bus company voted on the Landier contract, the board voted to void it. The board also prepared to sue Landier Transit to recover the money paid to the company during the years the three removed board members had voted on the contract.

Landier Transit bus. Courtesy Motor Bus Society.

School would begin on September 17, 1951; there was not enough time to open bidding, vote to select a new school bus operator and start service before then. Faced with the prospect of twelve thousand students having to find alternate transportation, the board voted on September 13 to enter an emergency forty-day rental agreement with Landier, ensuring that bus service would be provided until another company could be chosen.

The end of the school bus contract left F.P. with Landier Transit in Watts. Although F.P. had made a few improvements in the 1940s, he had focused primarily on his school bus service and never gave the transit system much attention or enthusiasm. In 1952, he offered to sell the system to Frank and Herbert Atkinson, operators of the neighboring South Los Angeles Transportation Company. The sale was finalized in 1953, and F.P. was out of the bus business.

F.P.’S FINANCIAL PROBLEMS CONTINUE

On October 24, 1952, the district sued F.P. and Landier Transit for $1.5 million, the amount paid to the bus company during the years the contract was voted on by Becker, Rounsavelle and Elliott. Probably knowing that his days in the school bus business were over, F.P. sought a settlement with the district.

F.P. and the district agreed on a settlement on August 17, 1954. F.P. was to pay the district $264,776.86 in eight yearly installments. If he missed a payment, he would be required to pay twice the outstanding balance, plus interest.

Although F.P. made payments in 1954, 1955 and 1956, by 1957 he was in serious financial trouble. Ethel Morris, the woman who had posed as his wife on the Yosemite trips, sued him in 1956 for $164,952, claiming that she acted as his housekeeper, secretary, nurse, dietitian and “business confidant” for him. F.P. paid an undisclosed settlement to her in 1959.

F.P., having difficulty making his settlement payment for 1957, asked the school board for additional time and presented the board a list of all of his assets and liabilities. Included was the Capistran Ranch, more than eight thousand acres of rugged land near the Mendocino County town of Covelo. Although F.P. had owned the ranch for several years, the ownership was now murky. F.P. had married Rose Heiner in 1957; that marriage lasted less than a year, and during divorce proceedings, the court granted her title to the ranch. Rose transferred the title to a title company in 1961. Complicating matters even further, F.P.’s first ex-wife, Honor, held a $50,000 lien on the ranch as part of her 1953 divorce settlement.

On June 14, the school system, fearing that F.P. was trying to prevent it from being awarded the ranch as part of the settlement, obtained an injunction prohibiting F.P. or any of the other titleholders from selling the ranch. A court battle over various legal aspects of the case raged for several years until 1969, when the school system was awarded 6,188 acres as payment for the settlement.

EPILOGUE

In May 1961, a company named CL Transit bid on a contract to transport handicapped students. The board quickly discovered that CL Transit was a shell company, lacking buses, drivers or even a garage. But what made the board take notice is that the company’s directors were all Landiers: F.P. was an advisor; his ex-wife, Honor, was president; and his son Paul was secretary-treasurer. Additionally, F.P. still owed part of the unpaid judgment from 1954. As the scandal of 1951 was still fresh in the board members’ minds, the board voted to decline CL Transit’s bid.

About a year after his failed attempt to resume providing school bus service, F.P. remarried once again and moved to Oklahoma City, where he worked in the construction industry until his death on January 3, 1968.

The Los Angeles City Schools and its successor, Los Angeles Unified School District (formed in 1961), retained ownership of the Capistran Ranch for about twenty years. Cattle grazing provided a steady source of revenue. One school official considered using the property as an educational campground, but its distance from Los Angeles, as well as its undeveloped state, made that idea impractical.

One has to work hard to find much of a trace of Landier’s operations. The Los Angeles Unified School District uses a mixture of directly operated and contracted companies to operate their school buses across metropolitan Los Angeles.

The Atkinsons operated the former Landier routes until 1968, when Dr. Thomas W. Matthew, an African American neurosurgeon and civil rights activist, bought the bus lines from the Atkinsons. He operated them as one of his many programs designed to provide “self-help” to the black community. Despite the doctor’s enthusiasm, financial problems shut down the bus routes in September 1971, and RTD provided replacement service from then on.

Over the years, bus service in South Central Los Angeles has been extensively modified, making it difficult to trace Landier Transit’s original routes. An exception is Metro Line #254, which connects Watts and Huntington Park via many of the same streets used by the former Landier Transit route.