CHAPTER 9

HELICOPTERS OVER TRAFFIC

Clarence Belinn’s Los Angeles Airways

Los Angeles, along with New York, Chicago and San Francisco, was once served by regularly scheduled helicopter service. Helicopters landed and took off in several Southern California suburbs, ferrying passengers to and from Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). A flight from San Bernardino to LAX, requiring up to two hours by car, would only take thirty minutes by helicopter.

Aviation pioneer Clarence M. Belinn, a strong proponent of helicopters, founded Los Angeles Airways (LAA) in 1944. LAA transferred passengers from the suburbs to LAX. Belinn also hoped that suburban commuters could use helicopters to go to downtown Los Angeles. However, high operating costs and two fatal accidents ended Belinn’s dream in 1970.

CLARENCE M. BELINN

Clarence Mauritz Belinn was born on October 24, 1903, in the coal mining town of Lanse, Pennsylvania. Most residents—including Clarence’s parents, Axel and Hannah Belinn—had immigrated to the United States from Sweden in the 1880s. Axel was a coal miner until 1916, when he opened a soda bottling plant. Clarence worked in his father’s bottling plant until joining the army in 1924.

Belinn enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and, in technical school, learned every aspect of aviation. He was stationed at Langley Field, Virginia, when a plane made an emergency landing in June 1925. Belinn quickly diagnosed a problem with the engine’s distributor and replaced the part. Years later, he learned that the pilot had been none other than aviation pioneer Igor Sikorsky.

In 1927, Belinn was stationed at March Field near Riverside, about seventy miles east of Los Angeles. The vastness of Southern California amazed him, as he noted it took more than an hour to drive from its distant suburbs to downtown Los Angeles. He envisioned a short-haul, “feeder” airline carrying passengers from the suburbs to the city and to the airport.

After leaving the army in 1929, Belinn found work at Washington–New York Airways as a pilot and mechanic. Shortly afterward, he worked at Ludington Airlines as superintendent of ground operations. When Eastern Air Lines acquired Ludington in 1933, Belinn moved to Boston-Maine Airways, as director of maintenance and engineering.

By this time, Belinn was well known in aviation circles. He helped Amelia Earhart prepare for her around-the-world flight in 1937 by adding an elaborate fueling system to her airplane.

Belinn became vice-president of Kansas City Southern Airlines in 1938. Two years later, he became vice-president of Hawaiian Airlines. He also served as director of the air transportation division of Matson Steamship Lines, where he sought to implement scheduled flights between Hawaii and the U.S. mainland. But he was rebuffed by the U.S. Civil Air Board (CAB), which ruled against steamship lines, railroads and other transportation interests owning airlines. In any event, civilian air transport was curtailed once World War II started.

In 1944, Belinn resigned from Matson to start Los Angeles Airways (LAA), the first scheduled helicopter airline.

HELICOPTERS TO THE RESCUE

Sikorsky and others had developed early forms of the helicopter, which had seen limited use toward the end of World War II. Originally, Belinn was skeptical about the hovering aircraft. “The traveling public should not be the guinea pig,” he warned, and he suggested small, fixed-wing airplanes instead. But discussions with Sikorsky convinced Belinn of the advantages of helicopters. Belinn coined the terms “heliport” (a full-featured airport serving helicopters) and “helistop” (a basic heliport with limited facilities). However, further development had to wait until the war ended.

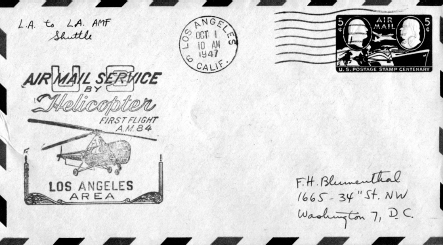

Airmail delivered by helicopter. Author’s collection.

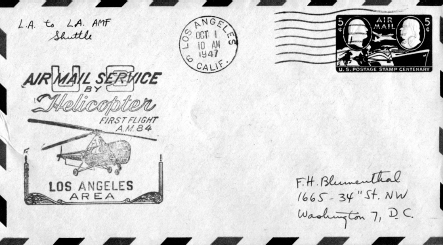

Los Angeles Airways route map. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

Meanwhile, the United States Post Office, which had experimented with army-operated helicopters to move the mail between airports and suburban areas since 1946, granted LAA a contract to carry mail from LAX to downtown Los Angeles and other points in Southern California.

In June 1947, the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) approved Belinn’s application to operate his scheduled helicopter airline. Service began on October 1, using Sikorsky S-51 helicopters on a shuttle route between LAX and the Terminal Annex Post Office in downtown Los Angeles. Two other routes served the San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys. A third route opened in 1949, serving Whittier, Long Beach and Santa Ana. The S-51 could carry ten passengers, but LAA removed most of the seats and filled the helicopters with mailbags.

Helicopter airlines started operating in Chicago in 1949 and in New York in 1953—both initially carrying mail only but adding passenger service within a few years. All three helicopter airlines had to develop methods, policies and procedures for training pilots, flying at night or in bad weather and using the radio and signaling systems.

PASSENGER SERVICE BEGINS

Belinn hesitated to carry passengers at first, as additional facilities—such as passenger waiting areas, ticket counters and baggage areas (and their associated personnel)—would be required. Therefore, although LAA was the first helicopter airline, it was not the first to carry passengers. That honor went to New York Airways in 1953.

For passenger service, LAA ordered two twelve-seat Sikorsky S-55 helicopters; these were modified to carry eight passengers and their luggage, along with the mail. Passenger service started on November 22, 1954, with six daily round trips between LAX and Long Beach. Within a year, passengers could fly to Orange County, Pomona, Riverside and San Bernardino; service reached Van Nuys in 1959. Fares varied by distance, topping out at ten dollars for a thirty-two-minute flight from LAX to San Bernardino, LAA’s longest route.

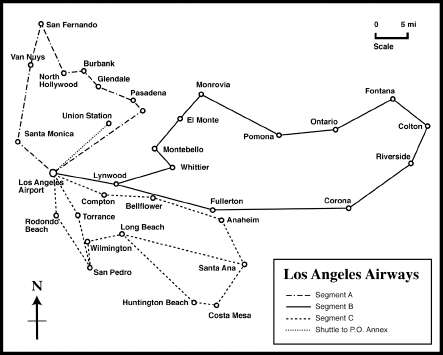

L.P. Doty and Clarence Belinn with a Sikorsky S-62. Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

In its first year of passenger service, LAA transported 10,000 passengers. The number of passengers carried increased each year until 1967, when it peaked at 396,000. Most customers were businessmen connecting to airlines at LAX. The Anaheim heliport, near Disneyland, was the busiest, carrying about 30,000 passengers per month, many of whom were tourists. Flights on December nights, providing a fantastic view of Christmas lights from above, were popular.

HELICOPTER MASS TRANSIT

In addition to serving LAX, Belinn desired to provide helicopters for people working in downtown Los Angeles. LAA helicopters would act as flying commuter trains, shrinking commutes of over an hour by road to thirty minutes or less. But there was no passenger heliport downtown. The heliport at Terminal Annex could only accommodate small helicopters, lacked passenger facilities and was too distant from most workplaces. The Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce suggested using a parking lot near the Civic Center for a heliport.

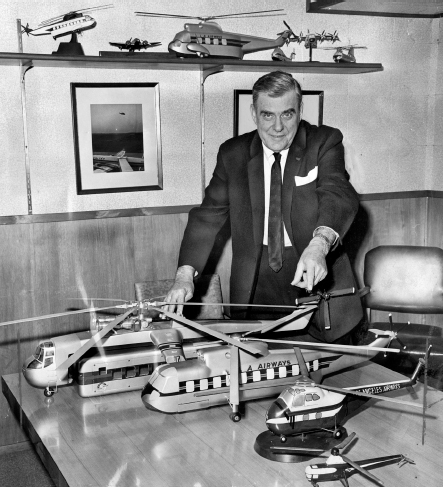

Clarence Belinn with model helicopters. Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Additionally, helicopter service was too expensive on a per-passenger basis to compete with driving or public transit. In December 1961, LAA purchased Sikorsky S61-L helicopters, each capable of carrying twenty-eight passengers. Belinn hoped that the future would bring huge, one-hundred-passenger helicopters. These large aircraft would theoretically have a per-passenger operating cost comparable to buses and trains, making helicopters economical for everyday commuting.

In 1961, the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Agency (LAMTA), which operated city buses and was planning a subway system, expressed an interest in helicopters as an additional mass transit mode. Subway stations could have heliports, theorized LAMTA officials. A few LAMTA officials took a demonstration trip on a LAA helicopter, but that was the extent of the agency’s involvement with helicopters. By 1967, LAA vice-president Robert Hubley expressed a more realistic viewpoint: “Mass rapid transit is not in the cards in the very near future, but maybe by 1985 or 1990 we may take another look at it.”

The city of Pomona built a heliport near its downtown transportation center in early 1968. At the groundbreaking, Belinn said, “The big job is to carry the passenger from his point of origin to his destination without any gaps. This can be done only by a transportation center that intermixes whatever mode is chosen by the customer.” Pomona’s transportation center provided access to passenger trains, city and regional transit buses, long-distance bus services…and helicopters.

THE END OF SUBSIDIES

Hoping that helicopter airlines would expand to more cities, the federal government had subsidized the three helicopter airlines since 1954. The subsidies were to be temporary; eventually, the airlines were to become self-sufficient. But several politicians, including President Lyndon B. Johnson, began questioning these subsidies. None of the helicopter airlines, having already received nearly $43 million in subsidies by 1963, was near financial independence. Neither did it seem equitable to subsidize a service used primarily by affluent businessmen while urban mass transit systems, which received little if any government funding, struggled to keep buses and trains running.

Subsidy opponents gained ground when SF-O Helicopter airlines opened in 1961. Founded by several former LAA executives, SF-O linked the cities and airports in the San Francisco Bay Area without a subsidy, primarily because its fares were about twice those of LAA. SF-O’s founders believed that the helicopter airline was a premium service and should be priced accordingly.

Los Angeles Airways Sikorsky S-61L over Los Angeles. Courtesy National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

Belinn, along with other helicopter supporters, testified about the importance of keeping the helicopter subsidies. Helicopters provided an essential alternative to travel over crowded streets and highways. And they could be deployed right away, while new highways and mass transit systems would take years, if not decades, to build.

Helicopters had proved their worth during the Korean War and were performing well in Vietnam. The supporters of subsidies argued that the helicopter airlines guaranteed a supply of trained helicopter pilots and mechanics for the military.

Before the Aviation Subcommittee of the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee, Belinn testified, “The economic justification [for helicopter subsidies] is a matter of record. Broad support is needed, however, as the national helicopter operation has become a matter of national concern. Disruption of this service would mark the first time in our country’s history when a project such as this has been abandoned for strictly political considerations.”

However, Congress voted to end the subsidies by 1965. The Chicago operation ended passenger service. LAA and New York Airways eliminated all but their most productive routes and sought support from the major airlines. LAA also discontinued its mail-only shuttle between downtown Los Angeles and LAX.

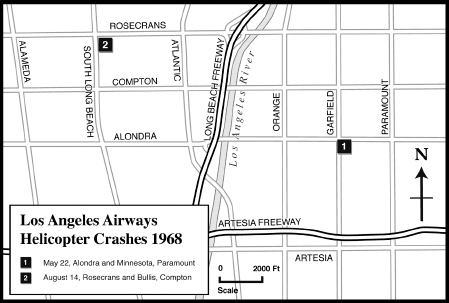

THE PARAMOUNT CRASH

From the beginning of passenger service in 1954 until the end of 1967, LAA had carried more than 1.6 million passengers without a major incident.

One day in May 1968, aircraft engineer Lu Zuckerman flew on an LAA helicopter between Disneyland and LAX. He noted the rougher than usual ride quality and, upon landing, noticed that one of the rotor blades was misaligned with the other four. He shared his observation with the ground crew, who assured him that the blade would be repaired during the helicopter’s next scheduled maintenance.

A few days later, that same S61-L left Anaheim for LAX at 5:40 p.m. Within ten minutes of takeoff, observers on the ground heard a loud snapping sound. Looking upward, they were horrified to see the helicopter rolling over and over as the tail rotor, and then a main rotor blade, flew off. The helicopter disintegrated as it descended, dropping parts and mail along the way. It crashed into a dairy farm in Paramount, striking the ground tail first and then exploding.

Several bystanders ran to the burning helicopter. They managed to pull one man out, but he had already been decapitated. The intense flames prevented any further rescue attempts. The crash killed all twenty passengers and three crew members on board, making it the deadliest helicopter crash in U.S. history. Among the victims were a family of vacationers; Mayor John Traynor of Red Bluff, California; and Dr. Arden Ruddell, a professor at University of California–Berkeley.

Mail sacks and wreckage were strewn over a 2,500-foot radius. The tail rotor ended up about a block away from the crash site, while the rotor blade pierced the roof of a nearby factory. (No one on the ground was injured.) Firemen and other rescue workers retrieved the bodies and took them to the morgue, while the helicopter parts were moved to a spare hangar at LAX for further investigation.

Los Angeles Airways schedule. Author’s collection.

LAA grounded all of its flights for a day, while the Federal Aviation Administration made a cursory safety check of the remaining S61-Ls. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, led by Kenneth Hahn, passed a motion asking that all S61-Ls be grounded until the cause of the crash could be found. Rumors that a midair collision or a bomb had destroyed the helicopter proved false.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) began the painstaking process of determining the exact cause of the crash. Rotor blades had penetrated the fuselage, striking passengers, and had separated the tail rotor from the aircraft. Investigators deciphered a garbled tape of the last communication between the pilot and air traffic control. The pilot was saying, “We’re crashing, help us!”

THE COMPTON CRASH

On August 14, Christopher Belinn, the fourteen-year-old grandson of LAA president Clarence Belinn, was traveling via LAA helicopter from his grandparents’ house in the San Fernando Valley to his parents’ home in Santa Ana. The flight from the Valley to LAX was uneventful. Christopher probably thought of starting school in a few weeks and competing on the track and cross-country teams. He and twenty other passengers boarded the S61-L for the trip to Anaheim. The aircraft lifted off at 10:25 a.m.

About eleven minutes later, witnesses on the ground reported seeing the tail rotor fly off the fuselage and then the helicopter plunging to the ground. It burst into flames as it landed next to Lueders Park in Compton. Observers noticed that the pilot seemed to be doing his best to control the doomed craft so as to land in the park, avoiding nearby houses. Once again, a few brave souls tried to rescue the passengers and crew, but the flames were too hot.

The curious thronged the area as the deputy coroners worked to remove the bodies. Standing by the tail section and doing his best to provide whatever help needed was Clarence Belinn. As he left the area, he said, “My grandson was aboard.”

The Compton crash marked the second deadliest in U.S. history, after the Paramount crash. NTSB, which was still investigating the earlier accident, had to handle this mishap as well.

WHAT WENT WRONG

NTSB released its findings for both crashes in 1969. The Paramount crash was caused by the failure of a blade damper, a device attached to each rotor blade to control excessive vibration. Since not all of the parts were recovered from the crash scene, it was impossible to discover what had caused the blade damper to fail in the first place.

Los Angeles Airways crash site map. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

As for the Compton crash, NTSB determined that the spindle linking the rotor blades to the hub had failed due to a crack in the metal, causing one of the blades to break off. With a blade missing, the helicopter became unbalanced, flipped out of control and crashed.

The S61-L’s spindles, as part of regularly scheduled maintenance, were to be replaced after every 7,500 flight hours. If a re-manufactured spindle was used, it was to be shot-peened. Vibrations from the helicopter’s engine caused microscopic fractures in the metal of the spindle. These fractures would grow into larger, dangerous cracks unless the spindles underwent a process known as shot-peening. In shot-peening, a series of tiny metal, glass or ceramic pellets, about the same diameter as a human hair, are shot at high speed at the metal to be treated. This treatment causes a slight deformation in the target metal, and any fractures are pushed together. Shot-peening also hardens the surface, making it less likely to crack due to metal fatigue.

According to NTSB, the spindle had not been shot-peened adequately, allowing the fractures to become larger and larger until the spindle broke apart.

THE SLOW DECLINE

A week after the Compton crash, LAA resumed regular flights. “We must move ahead. Public demand for our service is great, and we have no choice but to react immediately,” said a stoic Belinn.

But crash-fearing passengers stayed away from the helicopters. Ridership dropped from 1967’s high of 308,000 passengers to 39,000 in 1968 and fell sharply the following year. The Pomona heliport ticket agent reported that sales plummeted to 5 passengers per day.

Air taxi services, which operated on demand rather than a set schedule, attracted those former LAA passengers still willing to fly in helicopters. Commuter airlines, using small, fixed-wing airplanes capable of taking off from and landing on short runways, were another source of competition. These “short take off and landing” (STOL) aircraft were cheaper to operate than helicopters. LAA leased two DeHavilland Twin-Jet Otters for the San Bernardino route. Belinn considered these airplanes for future expansion to San Diego, Santa Barbara and Palm Springs.

In October 1969, LAA pilots, seeking higher wages and reduced flying hours, went on strike for almost seven months. LAA’s post-crash insurance rates quadrupled, while the major airlines, facing financial troubles of their own, withdrew their financial support.

WESTGATE AND HOWARD HUGHES

About one month before the Paramount crash, San Diego–based Westgate-California Corporation attempted to obtain a controlling interest in LAA. But since Westgate already owned Yellow Cab and an airport shuttle bus company, the CAB, citing conflict of interest regulations, barred the company from purchasing part of LAA.

Belinn sought support from industrialist Howard Hughes, who had provided some financial backing to LAA in the past. Hughes offered to buy LAA in 1968 but reneged on the deal two years later. (The initial decision to buy LAA had been made, not by Hughes, but by his head executive Robert Maheu. Other Hughes executives, jealous of Maheu’s position, convinced Hughes to cancel the LAA purchase.)

LAA sued Hughes, but it was too late to stop the helicopter airline’s financial free fall. LAA suspended all service in January 1971. Golden West Airlines, another commuter carrier, acquired LAA and operated helicopter service on the LAX–Disneyland route for about a year before it, too, went out of business.

Belinn spent the rest of the 1970s in court against Howard Hughes and his companies but lost on appeal in 1979. On December 23, 1988, Belinn passed away.

HELICOPTERS AFTER LAA

After the demise of LAA, several other operators attempted to provide helicopter shuttle service to LAX. On June 4, 1975, Los Angeles Helicopter Airlines started a route between downtown Los Angeles and LAX, using a helipad on top of the Hilton Hotel. Two months later, LAHA added routes to Montebello and Burbank. LAHA also suffered a fatal crash on November 22, 1977, near Burbank. LAHA ended its service in 1979 due to high operating costs and noise complaints.

The most successful post-LAA helicopter airline was Airspur, started by New York Airways founder John Gallagher in September 1983. It flew British-made Westland WG-30 helicopters on routes connecting LAX with Santa Ana (John Wayne Airport), Fullerton and Burbank. Airspur offered joint ticketing with several major airlines.

On November 7, 1983, in a near-repeat of the 1968 LAA Paramount crash, the tail rotor fell off an Airspur helicopter headed from LAX to Orange County. The craft spun out of control, tore through high-voltage power lines and landed a few hundred feet from the I-605 Freeway in Long Beach.

Although no one was killed or seriously injured, Airspur’s entire fleet was grounded for two months during NTSB’s investigation. The cause of the accident was determined to be a poorly designed lever controlling the tail rotor. After Airspur installed a redesigned rotor, the helicopters returned to the skies in early 1984.

But Airspur continued to have financial problems, and in November, Gallagher sold the airline to Oregon-based Evergreen Aviation. Evergreen was no more successful than Gallagher had been; on February 25, 1985, Airspur turned its last rotor.

Other short-lived helicopter airlines in Southern California included LA Helicopter, founded in 1986 by a former United Airlines pilot, and Helitrans Air Shuttle, which operated between Santa Ana and LAX in the early 1990s. None of these operations came close to providing the frequent commuter service envisioned by Belinn.

New York–based U.S. Helicopter, which had provided scheduled service from Manhattan to JFK and Newark Airports since March 2006, planned to expand to other cities, including Los Angeles. But high costs and the 2008 recession put U.S. Helicopter out of business in early 2009.

EPILOGUE

No scheduled helicopter service currently operates in Southern California. Island Express flies between Catalina Island and the mainland on a request basis only.

Helicopter noise continues to be an issue. Southern California is much more densely populated than in 1954, when Los Angeles Airways made its first flight. Residents under flight paths have protested against helicopter flights and blocked construction or use of heliports. Also lessening the need for helicopters to LAX is the major airlines’ use of suburban airports in Ontario, Santa Ana, Burbank and Long Beach.

The idea of scheduled commuter helicopters must still cross the mind of those stuck in Los Angeles traffic. However, unless technological advances reduce operating costs and noise levels, helicopters will probably never replace conventional ground-based public transportation.