CHAPTER 10

“WATTS WILL HAVE ITS BUS PARTY!”

Dr. Thomas W. Matthew’s Blue and White Bus

African Americans have contributed immensely to the transportation history of the United States. Garret Morgan invented the traffic light. Granville T. Woods invented several signaling and operational devices for railroads and streetcars. And Rosa Parks’s courageous refusal to give up her bus seat in 1955 led to the modern civil rights movement.

However, one African American transportation pioneer, who had a great deal of influence in the 1960s and early 1970s, is virtually unknown today. Recent African American history books do not mention him; other publications discuss his involvement with Ellis Island or Medicare but not his transportation projects.

DR. THOMAS W. MATTHEW

Thomas William Matthew, born in 1925, was the fifth child and first son of Daniel and Ethel Matthew, both immigrants from the British West Indies. Daniel worked as a janitor in various apartment buildings in the (then) all-white Bronx; he would house his family in the basements of these buildings. Because the nearby hospital did not admit African American patients, Thomas was born in the basement of one of these apartment complexes.

When Tom attended school, he was almost always the only African American student in the class. He often felt the sting of racism. One day in third grade, the teacher read Little Black Sambo to the class. “Once upon a time there was a little black boy, and his name was Little Black Sambo. Just like Tommy,” she said, pointing at him.

But Tom fought back. As a teenager, he joined the Bronx youth division of the NAACP. Protesting the segregation of New York City parks, he staged a successful sit-in at the parks department, demanding that a vacant lot in the Bronx be converted into a playground for black children.

His strong academic performance enabled him to attend the Bronx High School of Science and then Manhattan College, becoming the first African American to graduate from either school. He continued his education at Meharry Medical College. After graduating in 1949, he performed his internship at St. Louis City Hospital then his residency in Cleveland City Hospital. He hoped to become a neurosurgeon, but he found it nearly impossible to find a program admitting students like him. Finally, the elite Harvard Medical School accepted him in 1951.

In 1955, Dr. Matthew became the first black neurosurgeon trained in the United States. He returned to New York, held positions at Mount Sinai Hospital and became director of neurosurgery at Coney Island Hospital. Dr. Matthew started his own private practice in 1962 and served as a consultant for the New York State Boxing Commission. Despite an office on Park Avenue and a $100,000 yearly income, Dr. Matthew lived modestly in a brownstone in Harlem, enrolled his children in public schools and even refused to buy a third suit for fear of “being ostentatious.”

Dr. Matthew continued to be concerned about the poverty, substandard housing and limited access to healthcare affecting black citizens in sections of New York City. In 1963, he used his own money to found Interfaith Hospital, a 140-bed, nonprofit general hospital in Queens. Interfaith was the first hospital in New York State to be owned and operated by African Americans.

SELF-HELP, GROWTH AND RECONSTRUCTION

According to Dr. Matthew, slavery, discrimination and welfare had given many black people a bad attitude toward work. Therefore, he decided to make Interfaith Hospital not only a healthcare facility but also the centerpiece of several work training programs designed to teach people how to be successful in the workforce. These programs would help black citizens and other disadvantaged groups help themselves rather than live on welfare.

In 1964, Dr. Matthew, along with several community leaders, founded the Interfaith Health Association. Later, the association was renamed the National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization (N.E.G.R.O.). This organization operated not only Interfaith Hospital but also several other businesses, such as the Domco paint, chemical and textile manufacturing companies and the Spartacus Construction Company. N.E.G.R.O. companies made products used within the organization. Domco Textiles made linens and uniforms for Interfaith Hospital, and the paint factory’s products were used to maintain the hospital. Spartacus Construction rehabilitated apartment buildings for N.E.G.R.O.’s housing program and commercial properties for its multiple businesses.

Refurbishments often were done without permits or other official permission. Dr. Matthew felt that laws and regulations such as permit requirements were only “laws of convenience,” existing only to protect special-interest groups. Such laws, Dr. Matthew contended, were “not vital to society’s survival” and “inherently discriminatory,” as they kept black residents and other disadvantaged minorities from providing for their needs.

In the tradition of civil disobedience, Dr. Matthew was willing to break those laws, and pay any penalties incurred, if he believed it was in the interest of the African American community. Relations between Dr. Matthew and the city and state governments were contentious. Sometimes he would have his employees barricade buildings, preventing city inspectors or other officials from gaining access, as a form of protest.

To finance his projects, while avoiding the appearance of direct governmental help, N.E.G.R.O. sold “Economic Liberty Bonds,” or “N.E.G.R.O. Bonds.” These bonds were sold in denominations ranging from $0.25 to $10,000.00 and would mature in ten years. Dr. Matthew encouraged all sectors of society to buy the bonds. “You don’t have to be black to buy N.E.G.R.O. bonds,” he would often say.

However, Dr. Matthew did accept federal Medicare funds for providing patient care at the hospital, as well as Small Business Administration (SBA) funds for the work-training businesses. He even obtained contracts with the U.S. military to produce clothing and chemicals.

DR. MATTHEW STARTS A BUS LINE

Many of Dr. Matthew’s patients and workers did not own automobiles and relied on public transportation. However, the bus and subway lines in Queens, Harlem and other disadvantaged neighborhoods required several transfers. To improve transportation access to Interfaith Hospital and his other programs, Dr. Matthew started his own bus line. He acquired a few used buses and hired drivers, and on July 25, 1967, the first Blue and White buses went into service in Queens, linking Linden Avenue with Interfaith Hospital.

Blue and White Bus operated without a franchise from New York City. Dr. Matthew and city officials fought constantly over his right to operate the buses. He considered the franchise requirement another discriminatory “law of convenience” and vowed to continue the bus service. “Detroit is burning with $300-million worth of damage in a ‘hot’ riot,” he said. “What we are in the process of doing is creating a ‘cool’ riot. The cool riot, which we purposefully undertake, is doing things that will be productive for our group and all society, but couldn’t be done through bureaucratic red tape.”

A Blue and White bus in New York. Courtesy Johnson Publishing Company, LLC. All rights reserved.

In early 1968, the New York State Supreme Court ordered Dr. Matthew to stop running his buses. Dr. Matthew stated, “Judge or no judge, court order or no court order, the bus will continue to run,” and started an additional route in Harlem.

WATTS OR BUS(T)

By 1966, Dr. Matthew had given up his private practice in favor of focusing his full attention on his fast-growing, self-help organization. He considered expanding N.E.G.R.O. to other parts of the United States before looking at the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles.

In August 1965, a confrontation between Marquette Frye, a twenty-two-year-old African American, and a California Highway Patrol officer led to six days of rioting in Watts, leaving thirty-four dead, more than three thousand arrested and two hundred buildings destroyed. Both the leaders and citizens of Los Angeles, who associated race riots with older cities such as New York, Chicago and Detroit, wondered how one could happen in placid Southern California.

A state commission’s report, produced by former CIA director John McCone, told another story. The black population of Watts, which had grown during and after World War II, faced discrimination and police harassment on a daily basis. Prevented by racially restrictive real estate covenants from moving elsewhere, they had to put up with substandard housing and lack of access to jobs, education and healthcare. Underlying these issues was the lack of adequate public transportation.

PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION IN WATTS

Public transit ridership in and around Watts was high, since relatively few people owned automobiles. When the last Pacific Electric Red Car was replaced by bus service in April 1961, commuters’ trip times from Watts to Los Angeles were nearly doubled. Express buses provided high-speed service between Los Angeles and Long Beach via the new Harbor and Long Beach Freeways, but these routes bypassed Watts.

Since the mid-1920s, two local bus companies had served the area. Frank Atkinson and his son, Herbert, owned the South Los Angeles Transportation Company, which provided north–south service from a terminal at Broadway and Manchester, along Main, Central or Avalon, to downtown Compton. At Broadway and Manchester, passengers could transfer to Los Angeles Railway’s #7 streetcar (replaced by a bus in 1955) for service into downtown Los Angeles. The Atkinsons participated in the civic life of Watts and hired African American employees. During the 1965 riot, only one of their buses had been damaged.

The Atkinson Transit Company, also owned by Frank and Herbert Atkinson, had four routes radiating from 103rd Street and Compton Boulevard, at the heart of the Watts shopping district. Three of the routes extended from Watts to nearby Huntington Park, the Florence district and Compton. The Atkinsons acquired the routes in 1953 from Felicien P. Landier (Landier Transit). While South Los Angeles Transportation and Atkinson Transit were operated as separate entities due to differing labor contracts, passengers enjoyed free transfers between the two systems.

The Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority (LAMTA), which became the Southern California Rapid Transit District (RTD) in 1964, provided limited service. CPUC prohibited LAMTA or RTD from establishing routes in direct competition with any existing public transportation provider. The Atkinsons’ bus routes, therefore, prevented most RTD service from penetrating south of Manchester Boulevard. These restrictions were confusing and annoying to bus passengers.

Frank Atkinson, in his mid-seventies and eager to retire, expressed interest in selling the bus companies. However, his son, Herbert, genuinely concerned about the difficulties his passengers faced in traveling to downtown Los Angeles, was more interested in expanding service. Herbert sought to extend the Avalon Boulevard route, via a nonstop express route, into central Los Angeles and San Pedro, but he was blocked by the existing transit companies, which did not want competition on their routes to downtown.

BLUE AND WHITE BUS OF WATTS

Dr. Matthew, vowing to improve bus service in Watts with or without a franchise, offered nearly $500,000 for the Atkinson bus systems. This offer proved acceptable to Frank and Herb, and in December 1967, Dr. Matthew acquired both the South Los Angeles Transit Company and the Atkinson Transit System. He merged the two companies under the name Blue and White Bus Company of Watts and retained Herb as manager.

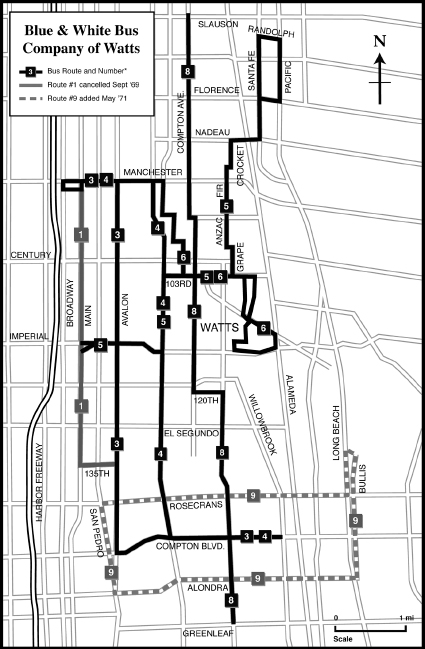

Blue and White bus route map. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

Dr. Matthew, having ended bus service in New York, had twelve buses driven overland to Watts. On the way, one of the buses collided with an automobile. Dr. Matthew, on board another bus, performed a life-saving operation using a ballpoint pen to hold the auto driver’s airway open.

Most of these buses broke down along the way; only three made it to Watts. Dr. Matthew declared that an additional twenty-seven buses were arriving by rail and promised not only improved service but also a board of community members to advise the bus company.

To strengthen the bus company’s financial condition, Dr. Matthew raised fares by a nickel. In July 1969, he asked CPUC for permission to cancel Route #1 (Main Street). Ridership along this route was low because the riot had destroyed many of the businesses on Main Street.

DR. MATTHEW AND PRESIDENT NIXON

Dr. Matthew’s pro-capitalist philosophies attracted the attention of political speechwriter Patrick Buchanan, who in 1966 introduced him to former vice president Richard Milhous Nixon. When Nixon became president, he wanted and needed the support of the African American community, though he did not wish to offend his base of conservative voters by promoting welfare-based programs. In Dr. Matthew and N.E.G.R.O., Nixon found a cause to champion, while the doctor became one of his biggest supporters.

In March 1968, the federal government charged Dr. Matthew with tax evasion. He freely admitted not paying $103,000 in income taxes and stated that he used the money to fund his self-help projects rather than giving it to the government for more welfare programs. He was convicted on October 20, 1969, and sentenced to five years at a federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut. However, Dr. Matthew had served a mere three months before Nixon, in his first act of clemency, pardoned him on January 6, 1970.

Nixon ordered members of his administration to “provide all possible support to Dr. Matthew.” Later, it would be discovered that administration officials had put pressure on other government agencies to ignore any problems with Interfaith Hospital and to suppress or destroy evidence showing that Dr. Matthew had misused government funds.

THE WATTS BUS PARTY

RTD, in response to the McCone Commission’s recommendations, expanded its bus route system in Watts and South Central Los Angeles. New routes provided east–west service along Century Boulevard and Imperial Highway and connected Watts with affluent West Los Angeles, Beverly Hills and Pacific Palisades.

Because east–west bus routes south of Manchester Boulevard were few, RTD added a new east–west route, #123 along El Segundo Boulevard, on February 8, 1971. This route provided access to the El Segundo aerospace firms in El Segundo and to St. Francis Hospital in Lynwood. The route crossed four of Blue and White’s north–south routes.

Dr. Matthew considered Route #123 an illegal violation of Blue and White’s service area and declared that the transit agency was trying to “destroy the people’s self-help bus line.” He provided a six-point list of demands to RTD:

RTD would voluntarily cancel Route #123, or any other route in Blue and White’s service area

RTD would lend Blue and White $3 million in operating capital

RTD would lend-lease 20 new buses to Blue and White

RTD would enter into a million-dollar contract for Watts to wash all of its buses for the next five years

RTD would turn over all its bus routes in Watts to the black community

RTD would enter into a “cultural exchange agreement” with Blue and White

Although some RTD officials expressed sympathy with these requests, the agency lacked legal authority to give money, equipment or bus routes to a private entity such as Blue and White. Dr. Matthew was not satisfied with RTD’s response to his demands. “Boston had its tea party, Watts will have its bus party!” he thundered.

On February 9, 1971, drivers on RTD’s Route #3, which served Sixth Street, downtown Los Angeles and Central Avenue, noticed that they were sharing the route with a bus of a different color. Two Blue and White buses were seen operating along the route, cutting in front of RTD buses and boarding passengers for free. While on board, Blue and White officials lectured the passengers on the feud between the two companies and asked them to support Blue and White.

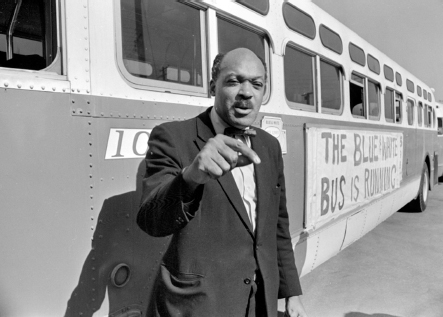

Thomas W. Matthew at Blue and White Bus yard in Watts. UCLA Charles E. Young Department of Special Collections, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives.

Although one of the Blue and White buses nearly struck a police officer, neither the police nor RTD made any effort to stop them, possibly fearing that a confrontation with Dr. Matthew would be publicized by the media.

Blue and White buses similarly shadowed Route #123 buses on El Segundo Boulevard. One RTD driver reported being harassed by Blue and White employees or supporters. In a February 12 letter to RTD, Dr. Matthew wrote, “The operation of free Blue and White service on your #3 route will continue and will extend as we see fit to other RTD lines. Should you decide to cease your illegal action and wish to negotiate the disagreement between RTD and Blue and White, we will, of course, be happy to meet with you.”

Blue and White operated its service over RTD Route #3 throughout February, while RTD continued to defend its Route #123 as legal because it provided a needed service under the recommendations of the McCone report. Only a few passengers on Route #123 would have chosen to use Blue and White buses instead, according to RTD.

DR. MATTHEW: HERE, THERE AND EVERYWHERE

As the N.E.G.R.O. businesses reached their peak in 1970, Dr. Matthew involved himself in several other projects. The most ambitious was improvements to Ellis Island, the historic entry point for millions of immigrants, including Dr. Matthew’s parents. However, since the mid-1950s, the buildings on the island had fallen into disrepair. Dr. Matthew planned to restore the buildings and then provide drug rehabilitation and job training programs, as well as tourist activities, on the island. After a thirteen-day demonstration in July 1970, when Dr. Matthew and sixty-three others occupied the island, the National Park Service gave N.E.G.R.O. a five-year contract to repair the buildings. But restoring the dilapidated facilities became a bigger job than Dr. Matthew anticipated; by September 1971, N.E.G.R.O. had abandoned the project.

In July 1971, Dr. Matthew led a delegation of nineteen N.E.G.R.O. employees to the Soviet Union to investigate the treatment of Russian Jews, comparing their situation with that of black citizens in the United States. Soviet officials, however, were not supportive of his efforts, and he returned after two days, rather than the six weeks he had planned.

Dr. Matthew was seemingly in several places at once, flying to Los Angeles to deal with Blue and White and then back to New York to manage the hospital and the Domco businesses. He started micromanaging the businesses and overextending himself. Business practices and financial accounting were careless; funds earmarked for one program were often shifted, either deliberately or inadvertently, to another.

Dr. Matthew’s connection with Nixon, as well as his own political beliefs, led him to support George Harold Carswell for Supreme Court justice, even though Carswell had supported segregation. Dr. Matthew, insisting that Carswell had been “rehabilitated” from his views in the same manner an addict could be rehabilitated from drugs, bought full-page newspaper ads supporting Carswell’s confirmation. He also disagreed publicly with other African American political groups such as the NAACP, even staging noisy demonstrations at the NAACP office. These actions alienated Dr. Matthew from mainstream black leadership. By this time, most African Americans were on the side of the NAACP and similar organizations and had little use for Dr. Matthew’s politics or programs.

BLUE AND WHITE WEEK IN COMPTON

The city of Compton, about three miles south of Watts, underwent a demographic change after the 1965 riots. Whites moved away, and African Americans started moving in.

Compton was served by three Blue and White routes and a few meandering RTD lines. Dr. Matthew, without asking permission from CPUC, added new Blue and White Route #9 in Compton on May 24, 1971.

The city staged a ceremony to inaugurate the new bus route. The Compton High School band played, a youth dance company performed and Mayor Douglas Dollarhide declared the week “Blue and White Bus Week.” He stated that Route #9 would “increase the community’s financial capability” by allowing greater access to jobs. Again, CPUC warned Dr. Matthew that the route lacked proper authorization but did nothing to stop it.

END OF THE LINE

Blue and White’s financial condition only worsened. In late June, the company failed to pay insurance premiums and lost coverage. Once CPUC found out, it suspended Blue and White’s operating certificate, making operations illegal until insurance was restored. But the buses rolled on.

Blue and White’s drivers, represented by the United Transportation Union, went on strike July 17 after the banks returned their paychecks for insufficient funds. “The buses will run even if we have to run over them,” threatened a Blue and White official. Strikebreakers, some of whom may have been “recovering addicts” from Interfaith Hospital, were hired to drive buses. Union drivers and strikebreakers argued, and some buses were vandalized. Blue and White operated about half of its regular scheduled service. Some of the buses were more than twenty years old, and breakdowns were common. On August 10, county marshals impounded the buses, keeping them off the street for two days until the union drivers had been fully paid.

On September 10, Internal Revenue Service agents stopped the buses, ordered all passengers to deboard and then towed the vehicles to an impound lot in Bell. Blue and White had failed to pay federal income taxes.

By this time, the community only wanted reliable bus service. And RTD was ready to provide it. The day after Blue and White’s buses were impounded, RTD hired the original Blue and White drivers and mechanics and began replacement service on all the former Blue and White routes, except for the unauthorized Route #9.

Dr. Matthew vowed to reinstate Blue and White, with new routes serving downtown Los Angeles and Disneyland. After a disastrous attempt at charter bus service, the company went out of business in 1972.

WHAT ABOUT INTERFAITH?

Conditions at Interfaith Hospital, once the centerpiece of Dr. Matthew’s organization, deteriorated until it became little more than an abandoned building housing a handful of “recovering” addicts but devoid of any medical staff. The hospital had also become a public nuisance. Several fistfights and a homicide at the hospital triggered an investigation that led to its closure and exposed financial irregularities in all of Dr. Matthew’s businesses.

On November 7, 1973, Dr. Matthew was convicted of diverting federal Medicaid funds intended for Interfaith to other projects, including Blue and White. Claiming that the funds went to “industrial clinics” for treating recovering drug addicts, he appealed his conviction, and on March 3, 1975, it was overturned. But his organization was now in shambles. The Domco textile and chemical factories were closed and their equipment repossessed to repay the SBA loans, which were now in default. And President Nixon’s resignation in August 1974 over the Watergate scandal left Dr. Matthew without any political allies. He returned to medical practice and disappeared from public view.

EPILOGUE

Although many disadvantaged people may have been helped by his programs, irregular bus service, understaffed health facilities and other half-completed projects undoubtedly hurt others. Dr. Matthew’s organization was just too ambitious to be sustainable. “Yes, I think I overextended myself,” he admitted in a 1973 New York Times interview. After the Blue and White Bus takeover, RTD (now Metro) expanded service, implemented a grid network of bus routes and opened the Metro Blue and Green light rail lines. Local bus systems—such as Watts DASH, Willowbrook Link and Compton Renaissance Transit—serve residential streets and other areas unserved by Metro.