CHAPTER 11

GROOVY BUSES TO THE BEACH

The Kadletz Brothers and the Pink Bus Line

On a warm summer morning in 1971, a small group of teenagers waits on Beach Boulevard, arms outstretched and thumbs pointed up, for a ride to Huntington Beach. They are all too young to drive, and all of their parents work or are otherwise too busy to drive them to the beach, so hitchhiking is the only way to get around—or is it?

In the distance, one of the teens notices a pink-and-white bus getting closer. Within a few minutes, it rolls up to the curb and stops. It is full of chattering teenagers with their surfboards and beach gear. The bus door opens, and the driver, who looks almost as young as his passengers, calls out, “Going to the beach?”

The group walks toward the bus. “Hey, wait a minute,” yells one teen. “Buses cost money.” He turns to the driver. “How much?”

“From here, a dollar twenty.” The teens dig into pockets and purses, find the required fare and board the bus, sending the coins clanking into the farebox before finding a seat. The ride is nothing but fun, with other teens to chat with and rock music booming from the onboard stereo.

Finally, the bus arrives at its last stop: the beach. “Last bus back is at 6:00 p.m.,” the driver warns as the bus empties.

THE KADLETZ BROTHERS AND THE PINK BUS

Michael Kadletz and his younger brother, Paul, spent their childhoods in the northern Orange County city of Brea during the 1960s. As teenagers, they often joined the group of young people hitchhiking to the beach on warm summer days.

After seeing the throngs of teenagers with their thumbs out, year after year, the two brothers decided that a bus to the beach not only would be safer but also would be profitable. Orange County bus service consisted of regional Southern California Rapid Transit District routes, carrying passengers to Los Angeles, Long Beach, Santa Ana and San Bernardino. North–south service along the county’s street grid was nonexistent. The new Orange County Transit District, voted into existence in 1970, did not operate any buses yet.

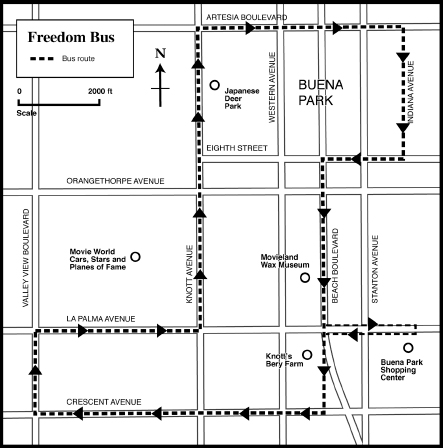

The Kadletzes proposed a simple twenty-one-mile line on Beach Boulevard, running from Whittier Boulevard in La Habra and then southward through the cities of Buena Park, Anaheim, Stanton, Garden Grove and Westminster before ending at Pacific Coast Highway in Huntington Beach.

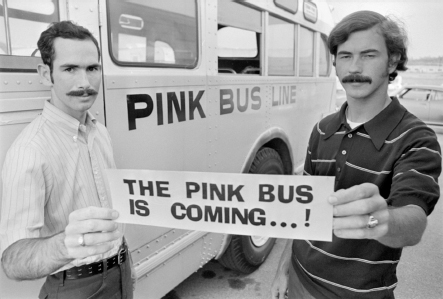

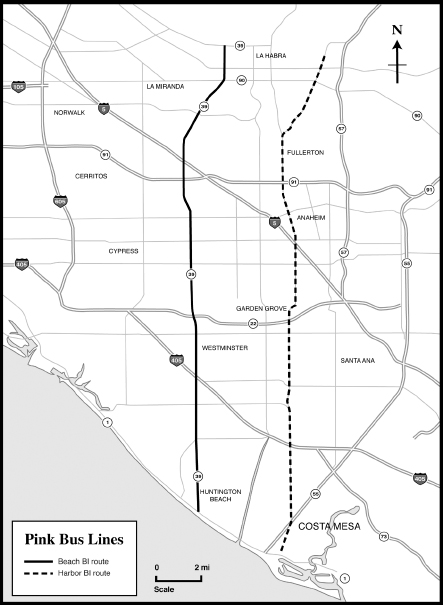

Mike and Paul Kadletz promote the Pink Bus. UCLA Charles E. Young Department of Special Collections, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives.

In 1970, using funds earned at a part-time supermarket job, Mike and Paul purchased two used 1954-model buses from American International Bus Exchange for $750 each. But they thought that the green-and-yellow paint scheme of the former Gardena Municipal Bus Lines vehicles was ugly, so they painted the buses an attention-getting pink and white, using house paint and a rented compressor.

To promote the new service, the Kadletzes bartered ads on and in the buses for ad space in newspapers and commercial time on radio stations. They also printed bumper stickers. Motorola provided free sound systems for the buses as a promotion for its stereos.

CONVINCING CPUC

Upon discussions with the cities, however, the Kadletzes learned that in order to legally operate the bus service, they would need a certificate from the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC).

Initially, CPUC officials were not convinced that the two brothers had the experience to run a bus line. “They laughed in our faces,” said Mike. But, undeterred, Mike and Paul set about to obtain the necessary certificate. They filled out a twenty-seven-page application, submitted it and waited. Officials from CPUC met with the Kadletzes in April to determine whether their proposed bus company would be financially stable enough to keep operating for at least three years.

“You can’t go into the bus business on a fly-by-night approach,” chided a CPUC staffer. The brothers planned to charge up to $0.60 for a ride along the entire line from La Habra to Huntington Beach; CPUC staffers convinced them that the fare needed to be doubled to $1.20.

Finally, CPUC granted a certificate to Pink Bus Lines on June 2, 1971. However, the Kadletzes still had trouble acquiring the required insurance coverage. The insurance company insisted that bus drivers be at least twenty-five years old. (At nineteen and seventeen, Mike and Paul were too young to drive their own buses!) The insurer’s reluctance to issue a policy delayed Pink Bus service for a few days. Only after a call from CPUC did the insurer provide the necessary coverage, allowing the Pink Bus to start rolling.

FIRST DAY OF SERVICE

The first Pink Bus left Whittier and Beach Boulevards on June 25, at 7:00 a.m. More than 225 teenagers rode the bus that day. The first bus filled up quickly, forcing the brothers to put their second bus on the street as fast as possible.

Once prospective passengers learned about the Pink Bus, all they had to do was walk to Beach Boulevard, wait for the bus and wave at it to stop. Once on board, riders enjoyed a party-like atmosphere. The buses’ sound systems played the latest hit songs. Alternatively, a rider might strum a guitar and serenade everyone. In the teen slang of the time, the kids thought riding the Pink Bus was “groovy.”

“The kids are great,” said driver Jerry Meng. “They don’t tear up the seats and they just sit back and dig the sounds.”

Riders who did not have the fare for the trip back home could leave their surfboard, swim fins or other equipment with the bus driver as collateral and pay the next day.

About 250 to 275 passengers caught the Pink Bus on weekdays, but weekend ridership was much less; apparently, teens obtained rides from their parents on weekends. The Pink Bus also attracted quite a few senior citizens, mostly on the “reverse” trips (northward from Huntington Beach in the morning and southward in the afternoons).

September came, and Pink Bus’s young patrons went back to school. The Kadletzes reduced service to operate on Monday, Wednesday and Friday only; by September 17, service was suspended entirely. The brothers had made $14,000, before expenses. “Business would have been better yet if the PUC hadn’t delayed us. We didn’t have time to advertise before the end of school,” remarked Mike.

FREEDOM BUS LINES

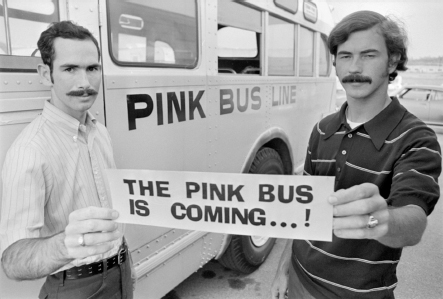

The Kadletzes wanted to continue providing bus service during times when the beach runs were unprofitable. In October, they started Freedom Bus Lines, a shuttle bus in Buena Park serving attractions such as Knott’s Berry Farm, the Japanese Deer Park and Movieland Wax Museum. Buses painted in a patriotic scheme of red, white and blue looped through town every hour. Freedom Bus Lines operated until May 1972.

Freedom Bus Lines route map. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

THE PINK BUS GOES TO COLLEGE

Another source of year-round income came from university campus shuttles. In 1972, OCTD and the University of California–Irvine provided a $6,000 grant to Pink Bus Lines to provide a shuttle service to and from campus. Parking at UCI was limited, and existing South Coast Transit bus service was very infrequent. Many students chose to hitchhike.

The fare-free UCI shuttle, which started in September, operated in a one-way loop between campus and Newport Beach, stopping at student apartment complexes along the way. Occasionally, a professor would hold an impromptu discussion session onboard, turning the bus into a rolling classroom.

Although the shuttle was intended for faculty, staff and students, drivers picked up anyone along the route who wanted to ride. South Coast Transit, whose routes the Pink Bus partially duplicated, complained that the free Pink Bus service was illegal competition. The university then declared the Pink Bus shuttle a “school bus” and noted that it would only transport students (no faculty, staff or visitors allowed). South Coast Transit, still not mollified, filed a protest with CPUC against UCI and Pink Bus on January 27, 1973. Eventually, UCI was able to convince both the transit company and CPUC that non-students would not be carried, and South Coast Transit dropped its protest in May.

By February, Pink’s UCI shuttle was carrying about three hundred passengers per day. While buses ran full in the morning, afternoon runs were less productive. Because the route was a one-way loop, a student living close to campus might have a ten-minute ride to class but would have to endure a thirty- to forty-minute ride back home. Some students would ride one way and then hitchhike for the return trip. Bus breakdowns happened often; the driver was usually forced to attempt a quick repair, as backup buses were rarely available.

The Pink Bus shuttle continued until the end of the school year in June. By the time classes resumed in September 1973, OCTD had acquired South Coast Transit and improved service to UCI, so the Pink Bus shuttle was no longer needed.

In 1973, the Kadletzes acquired the San Diego State University’s Bug Line, which connected the campus to San Diego’s beaches. Journalism professor Jack Haberstroh, concerned about student hitchhiking, started the fare-free Bug Line in 1972 as a class project. Students drove and repaired the buses, which were decorated as gigantic insects with huge fiberglass eyes and antennae. Students also sold advertising to cover the bus line’s costs. However, operating responsibilities became too much for Haberstroh and his students to handle, so he sold the Bug Line to the Kadletzes.

The Kadletzes added to the buses trailers capable of carrying fourteen bicycles. However, drivers’ wages (Pink Bus used professional drivers instead of volunteer students) and rising fuel costs required that a ten-dollar monthly fare be charged. The fare, plus improvements in San Diego Transit’s local bus service, caused Bug Line ridership to fall. After school ended in June 1974, the Bug Line was canceled.

HARBOR BOULEVARD

OCTD continued to add routes. On April 13, 1973, the agency started a new line on Harbor Boulevard, linking Fullerton to Newport Beach. OCTD also planned a route on Beach Boulevard but was legally barred from operating service competing with a private bus operator. If OCTD wanted to operate on Beach Boulevard, where Pink Bus Lines already operated, it would have to acquire Pink Bus first. By law, the purchase price had to be at least the average revenue over the past three years. But the Kadletzes wanted a much higher price for their bus line.

On the other hand, the Kadletzes were concerned that an OCTD route along Harbor Boulevard, four miles east of the Pink Bus route, would attract their passengers. The Kadletzes filed not only a protest with CPUC against OCTD’s Harbor Boulevard proposed line but also an application for their own new route on Harbor.

“They consider that anything within five miles will divert passengers from their line,” complained OCTD general manager Pete Fielding. However, Mike Kadletz noted that passengers in northern Orange County could still take advantage of the new OCTD line by riding La Habra’s dial-a-ride (a small bus, operating like a taxi) to a Harbor Boulevard bus stop and then transferring to the OCTD bus to Newport Beach. OCTD charged $0.50 for this trip, as opposed to Pink Bus’s $1.20 fare for a ride from La Habra to Huntington Beach.

“We’d like to remain in business and could do so, if the Transit District does not begin a north–south run that would compete with us,” said Mike Kadletz. But he was also considering selling the Pink Bus to OCTD at an undisclosed price.

OCTD director John Kanel, surmising that the Kadletzes’ Harbor Boulevard application was engineered to force OCTD to acquire the company, remarked, “They may be young and operate old buses, but I don’t see them as martyrs like some of the newspapers picture them. I’d say they are pretty sharp operators.”

Pink Bus Lines route map. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

On May 14, OCTD, which had offered to purchase Pink Bus Lines for $30,000, raised its offer to $32,000. The Kadletzes had until May 22 to either accept or reject the offer.

By June, OCTD officials, losing their patience with the Kadletzes, made a final offer to Pink Bus. If the Kadletzes refused the offer, OCTD would take them to arbitration to determine a price for the bus line. If arbitration failed, the next step would be court action to acquire Pink Bus through condemnation, and a court would set the price OCTD would pay for Pink Bus.

The Kadletzes, however, refused OCTD’s final offer, claiming that it would not compensate them for expected fare revenues of about $30,000 for the upcoming summer season. Instead, they sued the transit district, seeking an injunction to stop the transit district from operating its Harbor Boulevard route. They claimed that Pink Bus Lines was losing $1,000 per week due to competition from OCTD and was in danger of shutting down.

On August 6, OCTD and the Kadletzes finally reached an agreement. OCTD would buy Pink Bus Lines’ “objection rights” for $24,000. This meant that Pink Bus and OCTD could both operate along Beach and Harbor Boulevards, without Pink Bus objecting to the presence of OCTD service. Also, both OCTD’s condemnation suit and Pink Bus Lines’ charges of unfair competition would be dropped. Pink Bus service on Harbor Boulevard started on July 26, with four round trips per day. OCTD began its Beach Boulevard service on September 11, after Pink Bus Lines had ceased operations for the season.

OF AARDVARKS AND TEUTERBERGS: END OF THE PINK BUS LINE

During the struggles with OCTD, Paul Kadletz, deciding to pursue other interests, sold his share of Pink Bus Lines to Howard Ahmanson Jr., son of Home Savings founder Howard Ahmanson. Pink Bus Lines acquired five additional used buses shortly thereafter. Mike Kadletz, along with his new partner, planned to expand next summer’s beach bus service northward from La Habra to Hacienda Heights and open a new route to Pomona.

Instead, in April 1974, Mike and Howard sold the Pink Bus Lines to Alwin Teuterberg, who renamed the company Aardvark Bus Lines. Teuterberg was only interested in operating charter bus service. By this time, OCTD was providing regular service on Beach Boulevard, and the Pink Bus became a fading memory.

GOOD TIME TOURS: DAVID FIGHTS GOLIATH AGAIN

In 1977, Mike started Good Time Tours, a sightseeing bus company that picked up passengers at Orange County hotels and took them on tours of Palm Springs.

Much to his dismay, the large, internationally known Gray Line Tours started its own Orange County–Palm Springs tour. Gray Line, whose rights to operate such a tour predated World War II, had not done so since 1965. Gray Line, being much better known than the fledgling Good Time, ended up getting most of the tour business, causing severe financial difficulties for Mike’s company.

Mike filed a complaint to CPUC against Gray Line. Not only did he think it was unfair that Gray Line could leave its operating rights dormant for years and then suddenly reactivate them, but he also felt that he had put thousands of dollars into Good Time and Gray Line was taking advantage of his efforts.

CPUC agreed. Its precedent-setting ruling noted, “Unused operating authority should be revoked. It is not equitable nor in the public interest for carriers to retain or collect unused operating authority which they can activate or put in dormant status at will.” Gray Line’s authority was revoked, but it was too late for Good Time Tours; the financial damage had been done. Good Time ceased operating in early 1980.

EPILOGUE

Although out of the scheduled and charter bus business, Mike Kadletz’s interest in buses has remained strong over the years. Nowadays, instead of operating buses, he converts them into luxury motor homes. Since 1991, he has published Bus Conversions, a magazine for people converting old buses to motor homes.

The Orange County Transit District became the Orange County Transportation Authority in 1991. Its Route #29 provides frequent service on Beach Boulevard between La Habra and Huntington Beach. On a warm summer day, a few beachgoers with surfboards, coolers and other beach gear will ride. But OCTA #29 is nowhere near as quirky as the bright pink buses cruising along Beach Boulevard, with their stereos on full blast and drivers almost as young as their passengers.