CHAPTER 12

DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER

Adriana Gianturco and the Diamond Lane

Nearly every freeway in Southern California features a carpool lane. Otherwise known as “High Occupancy Vehicle” (HOV) or “Diamond” lanes, they offer a faster trip for those commuters willing to give up the convenience of driving solo.

While most commuters, carpoolers or not, now accept carpool lanes, the first attempt to provide them on a Southern California freeway in 1976 was met with anger, protests and lawsuits. The Santa Monica Freeway Diamond Lane Project was ended in a matter of months, and it would be nearly a decade before another carpool lane opened. Finally, the project also altered the career course of Adriana Gianturco, the first woman appointed director of a state highway department.

ADRIANA GIANTURCO

Born in Berkeley, California, on June 5, 1939, Adriana Gianturco was the oldest child of Elio and Valentina McGillicuddy Gianturco. A year later, the Gianturcos moved to Washington, D.C. Adriana grew up on the East Coast. She attended Smith College before returning to California in 1960 for a master’s degree in economics at the University of California–Berkeley.

After graduation, her attempts to find work met with much discrimination, and there was little open to her but secretarial jobs. Having been asked, “How fast do you type?” too many times, she decided to seek employment outside of the United States. She traveled through the Middle East and Europe, eventually settling in Paris, where she worked as a reporter for Time magazine for two years.

In 1964, Gianturco returned to the United States and enrolled in the urban planning program at Harvard University. While in Boston, she worked for two nonprofit social service agencies, Planning Services Group and Action for Boston Community Development, and then became director of planning at the Massachusetts Office of State Planning and Development. In all of these organizations, she worked to preserve older neighborhoods by stopping freeway construction. She also met John Saltonstall Jr., a Boston city councilman. They married in early 1970.

CALIFORNIA HIGHWAYS: END OF AN ERA?

The big boom of freeway construction had taken place in the 1950s and ’60s. Engineers drew lines on maps, put contracts out to bid and started up the bulldozers. Gasoline taxes provided plenty of funds for construction. Freeways were built with minimal regard for existing land use. The multi-lane roads cut through mountains, open space, wetlands and neighborhoods, but construction was heavily supported by local government officials as a source of jobs, an impetus for development and a visible result of the taxes paid to Washington and Sacramento. Freeway construction satisfied engineers, politicians, the “highway lobby” (automobile, tire and oil companies), land developers and, at least initially, the general public.

By the early 1970s, however, Californians had begun expressing concerns over the environmental and social effects of freeways. Construction was disruptive and uprooted residents, and when finished, the freeways generated noise and air pollution. They also cut neighborhoods in half.

“Freeway Revolts” took place across the state, making it increasingly difficult to plan or build any more freeways. Additionally, funding from gasoline taxes became less able to cover the ever-increasing costs of construction. That meant less work for the highway engineers. Some of them were laid off, leaving the remaining engineers demoralized.

The California Department of Highways became the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) in 1973, reflecting the state’s interest in planning for other modes of transportation, such as public transit, intercity rail and pedestrian and bicycle facilities. The highway engineers, who had spent most of their careers designing and planning new freeways, grumbled about the shift in the department’s priorities.

JERRY BROWN AND APPOINTMENT

On November 5, 1974, Jerry Brown was elected to his first term as California governor. He made an effort to appoint women, minorities and environmentalists to important government positions. Gianturco, who had met Brown while attending UC–Berkeley, was in Boston completing her PhD in urban planning. She had only her dissertation left to complete when Governor Brown appointed her as director of Caltrans.

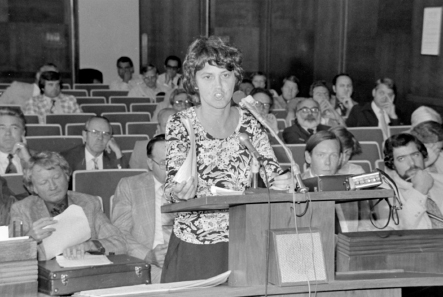

Adriana Gianturco. UCLA Charles E. Young Department of Special Collections, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives.

HIGH OCCUPANCY VEHICLE LANES

Interest in HOV lanes began in the early ’60s. Increasing traffic congestion, along with pressure from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to reduce automobile emissions, led transportation and governmental officials to promote alternatives to driving alone. “Move people, not cars” became the rallying cry.

The first HOV lane in the United States was a twelve-mile, reversible bus–only lane on the Shirley Highway (I-395) between Northern Virginia and Washington, D.C. In Southern California, the El Monte Busway, eleven miles of bus-only lanes on the San Bernardino Freeway (I-10) between El Monte and Los Angeles, opened in January 1973.

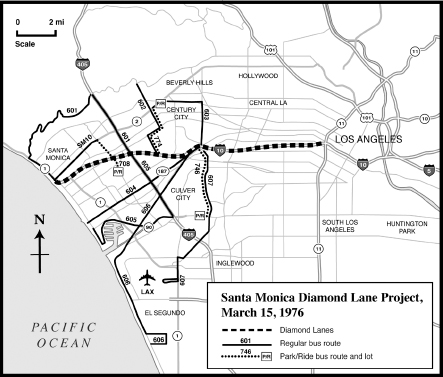

In December 1973, the California State Senate passed a resolution (SCR 84) directing the state department of transportation to implement a HOV lane program. By 1974, the State of California, County of Los Angeles and City of Los Angeles had chosen the Santa Monica Freeway for a pilot project. During morning and evening rush hours, the freeway lanes closest to the median (the “fast” lanes) would be reserved for buses and carpools carrying three or more people. These lanes would be marked with diamonds, the symbol used to mark HOV lanes elsewhere in the United States.

In addition to the reserved lanes, ramp meters, or special traffic signals, were installed at each on-ramp in April 1975. These signals limited the number of cars allowed to merge onto the freeway, keeping traffic free flowing.

Because of a labor dispute with the Southern California Rapid Transit District (RTD) bus driver union, the opening date of the Diamond Lane, originally planned for June 15, 1975, was delayed until March 15, 1976—just in time for Gianturco’s first day as director of Caltrans.

THE DIAMOND LANE’S FIRST DAY

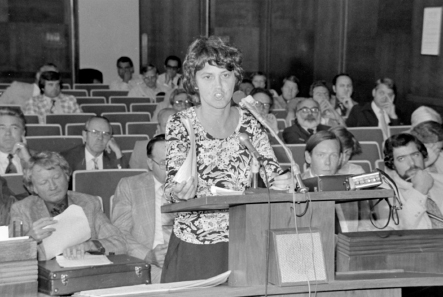

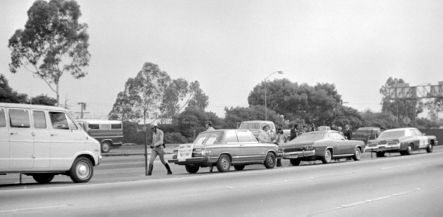

For Santa Monica Freeway commuters, that day could only be described as chaos. The Diamond Lanes provided a faster ride for those who could carpool or take the bus. For everyone else, who now had only three lanes to cram into, it was a different story.

Traffic crowds into remaining mixed-flow lanes, while Diamond Lane traffic moves quickly. UCLA Charles E. Young Department of Special Collections, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives.

Santa Monica Municipal Bus Lines #10 (Diamond Lane route). Courtesy Santa Monica Big Blue Bus.

Diamond Lane bus route map. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

Solo commuters complained of trips taking twice as long. Ramp meters backed up traffic onto surface streets. Abrupt movements abounded as drivers transitioned from the fifty-five-mile-per-hour traffic in the Diamond Lane to a mixed-flow lane moving about five miles per hour. The average accident rate on the freeway jumped from two per day to twenty-five per day over the duration of the project.

On the following day, traffic conditions in the mixed-flow lanes improved only slightly. Complaints from drivers filled the op-ed pages of newspapers, blared over talk radio and clogged the Caltrans Diamond Lane telephone information line.

Some people thought Caltrans had a more sinister intent. They equated the Diamond Lane with socialism and communism. Comments such as, “We are seeing on the Santa Monica Freeway the beginning of the end of freedom of movement in the United States and the birth of a Soviet America,” and “Those diamonds out there are Big Brother’s heel marks, and they are beginning to look more and more like the hammer and sickle every day” filled newspaper op-ed pages.

Media coverage was mostly negative. During the months in which the Diamond Lanes were in effect, nearly every issue of the Los Angeles Times, the Herald Examiner and the Santa Monica Outlook featured articles with titles such as “Freeway Folly,” “Dishonesty with Diamonds” and “Sin and the Diamond Lanes.” Cartoonists, such as Paul Conrad of the Los Angeles Times, drew cartoons denouncing the project.

Local radio and television stations reported on the Diamond Lanes. While traffic reporters and disc jockeys made jokes about the traffic backups, television newscasters provided a platform for politicians and activists to present their opinions about the project. Articles about the Diamond Lane appeared in nationwide media outlets.

But Caltrans officials dug in. Donald Burns, head of the state Business and Transportation Agency overseeing Caltrans, said, “Now we expect a lot of howling from enraged motorists.” He added, “Now we are prepared to suffer considerable public outcry in order to pry John Q. Public out of his car.”

CITIZENS AGAINST THE DIAMOND LANE

The protest movement against the lanes started off small. Paint and nails were thrown in the Diamond Lanes, and people gave away “No Diamond Lane” bumper stickers at freeway on-ramps.

On March 29, 1976, attorney Eric Jubler filed a lawsuit in the California Superior Court, alleging that the Diamond Lanes had lacked the proper Environmental Impact Report. He also claimed the lanes violated several parts of the United States Constitution. The Pacific Legal Foundation, a Sacramento-based public advocacy legal organization, filed a similar suit in the United States District Court on April 9.

In early May, Randy Kirk formed Citizens Against the Diamond Lane (CADL). The group grew to about eighty members. “My phone hasn’t stopped ringing since last Thursday with calls from people who want to join with us to end this project. We don’t feel the bureaucracy has a right to impose its solutions on the people without their ever having a chance to approve these solutions at the ballot box.” CADL protested against the lane as far away as Maryland, at one of Jerry Brown’s presidential campaign appearances.

Anti–Diamond Lane protest on freeway. UCLA Charles E. Young Department of Special Collections, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives.

Anti–Diamond Lane protest. UCLA Charles E. Young Department of Special Collections, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives.

Anti–Diamond Lane protest at Brown campaign headquarters. Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

CADL staged a novel protest on June 3. A mock funeral procession, complete with hearse, drove on the Diamond Lanes from Santa Monica to downtown Los Angeles, terminating at Jerry Brown’s presidential campaign headquarters. Twenty protestors were cited for driving in the lane with fewer than three passengers.

Although the Diamond Lanes were not Gianturco’s idea, she liked the concept and became a big proponent of them. In a July 21 interview, Gianturco reaffirmed her support for the Diamond Lanes. She said, “We believe that there is real merit to this kind of project. It’s designed to do three kinds of things. One is to decrease air pollution, secondly conserve energy, and, third, do something about the terrible congestion problems we have. And it’s supposed to increase carpools and bus riders, and it’s done that. And, it’s on those grounds that we think it’s working; it’s not that we are just out there doing something for the hell of it, essentially.” By this time, Gianturco and the Diamond Lanes were inextricably linked in the minds of many Southern Californians.

CADL held another protest on August 2 at Caltrans headquarters in downtown Los Angeles. The protestors were dressed in cloth bandages to symbolize those injured in Diamond Lane–related accidents. They displayed a petition with four thousand signatures calling for the end of the Diamond Lane.

END OF THE LANE

On August 9, U.S. District Judge Matt Byrne ruled that Caltrans had implemented the Santa Monica Freeway Diamond Lane without filing the necessary environmental impact report. He ordered the project ended, and the lanes returned to general use, by August 13.

The next day, lone drivers swarmed into the Diamond Lane with a vengeance. The California Highway Patrol announced it would no longer enforce the three-people-per-vehicle rule. Traffic now flowed smoothly in all lanes.

In a televised debate with Los Angeles city councilman Zev Yaroslavsky, the Caltrans director conceded defeat. “We have lost this court suit,” Gianturco said. But she continued, “We plan to appeal. We believe that on the merits of this project, it is the kind of way to go. The people of Los Angeles have demonstrated time and time again that they do not want to spend money for mass transit in any significant amounts,” referring to a rapid transit sales tax measure that was voted down in June. “In the absence of preferential treatment and encouraging buses and carpools, I don’t know where we go.”

By mid-August, the Diamond Lane signs had been removed and the ramp meters reset to a less aggressive cycle. Only the diamonds painted on the freeway remained, to be sandblasted away within weeks.

SAN DIEGO FREEWAY DIAMOND LANE

While struggling with the Santa Monica Freeway project, Caltrans announced plans for another Diamond Lane on the San Diego Freeway (I-405) between West Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley. Unlike the Santa Monica Freeway project, which removed two lanes from general use, this Diamond Lane would be constructed from the northbound left-hand freeway shoulder. A southbound Diamond Lane would be added later.

Even though no existing lanes would be taken away, opposition to the project appeared immediately. After Yaroslavsky warned that the project would “back traffic clear up to the city of Beverly Hills,” the council voted nine to one to sue Caltrans if the agency did not halt the Diamond Lane.

Gianturco said, “We have learned from the Santa Monica Freeway experience that we need more citizen participation. We didn’t do enough of that and it backfired.” She continued, “If that means delaying it, then we will. We need three or four months before moving ahead with the project.” The City of Los Angeles dropped its plans to sue Caltrans when it learned the lane would not open until at least January 1, 1977.

On January 29, the lane opened to all drivers, not just carpools. Caltrans officials warned drivers not to use the southbound shoulder, which had not been opened as a traffic lane.

ADRIANA THE OUTSIDER

The nearly all-male cadre of highway engineers balked at the idea of a woman leading Caltrans, although few expressed their views publicly.

More infuriatingly, she was not an engineer, but a planner. What did she know about building highways? The engineers thought that they should be directed by someone who knew about building highways, not an “urban planner” more interested in carpool lanes, mass transit and other alternatives to roads. During the Diamond Lane project, one engineer groused, “Most of us wished we were back building freeways.”

Gianturco was not known for a friendly disposition, whether dealing with engineers, legislators, other government officials or the general public. “She’s quite articulate. But she can’t say ‘hello’ without sneering,” said Albert Rodda, a former state senator. Councilman Yaroslavsky noted, “She could have sold the Diamond Lane if she had educated the public rather than hitting them over the head with a hammer.”

FREEWAY SLOWDOWN

During Gianturco’s tenure as Caltrans director, freeway construction came to a near-standstill, as many projects were delayed, deferred or removed from the master plan. The Foothill Freeway (I-210) between La Verne and San Bernardino languished incomplete for decades. The Long Beach Freeway (I-710) segment through South Pasadena was never built. Although the real reasons were either lack of funds or local opposition, freeway supporters, both inside and outside of Caltrans, accused Gianturco of deliberately stalling the projects in order to force drivers to switch to public transportation.

The Century Freeway (I-105), linking Los Angeles International Airport and Norwalk, had been on the freeway master plan since at least 1956. Because it cut through poor and minority neighborhoods, residents of South Central Los Angeles, Willowbrook and Lynwood banded together and filed suit to stop construction. Court battles delayed the project for about a decade. By the time construction began in 1982, the proposed $100 million, ten-lane freeway had become a $2.2 billion project with six freeway lanes, two carpool lanes and light rail in the median. Residents also demanded and received replacement housing, job training and affirmative action programs to ensure that they were hired to build the freeway. The Century Freeway finally opened in October 1993.

In September 1976, the California Highway Commission, in a five-to-one vote, ordered Gianturco to start authorizing construction of additional freeways. She had been keeping about $309 million in reserve for maintaining the current freeway network. San Diego mayor Pete Wilson said, “We have to continue to finish off the freeway system. Perhaps [Jerry Brown and Gianturco] are deluding themselves by thinking that by not spending the freeway funds, they’re going to be able to build some kind of a mass transit system.”

California state assemblyman Walter Ingalls and state senator Alfred Alquist, both longtime critics of Gianturco, introduced legislation in 1977 that would remove some of Caltrans’s authority. Their Assembly Bill 402 would replace the Highway Commission with a new California Transportation Commission. It would also create local transportation commissions, including the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (LACTC). Most notably, the bill would transfer funding decisions from Caltrans to the legislature. Governor Brown signed AB 402 into law on September 28, 1977, over Gianturco’s objections.

“GET GIANTURCO OUT!”

To her political enemies, it was not enough simply to undermine Gianturco’s authority. They wanted her out. Shortly after the lane on the San Diego Freeway opened in January 1977, Assemblyman Paul Priolo said of Gianturco, “She’s incompetent, she’s arbitrary and dogmatic in the matter in which she handles things. Her background is at best questionable, her performance has been inept, and it’s time to get rid of her. [Brown’s] sense of loyalty to these people I think is distorted and he ought to wake up. Now’s the time to get rid of Adriana.”

In May 1979, the legislature voted on a budget for Caltrans, omitting Gianturco’s $40,000 annual salary. The vote was merely symbolic, since she would be still paid from contingency funds or other sources.

The clamor for Gianturco’s removal increased. In April 1981, Ralph Clark, chairman of the Orange County Board of Supervisors, called for a resolution asking Governor Brown to fire her. This action was spurred by a draft state transportation budget halving Orange County’s transportation fund allocation. “This is Adriana Gianturco’s version of highway robbery,” said Clark. “I agree that we have to go to war and the best place to start is to ask for her resignation or for the governor to fire her.” Alquist sponsored a bill requiring the Caltrans director be a licensed civil engineer. The bill did not pass.

AN OCCURRENCE AT TOWN CREEK BRIDGE

Gianturco and the highway engineers clashed over the Town Creek Bridge on California Highway 162 near Covelo, Mendocino County. Although the bridge carried a few vehicles per day, years of use by logging trucks had weakened the twenty-two-foot-wide bridge. Caltrans engineers recommended a new forty-foot-wide bridge, but Gianturco insisted that the new bridge be only thirty-two feet wide, costing $29,000 less. Two Caltrans officials, incensed that Gianturco, a non-engineer, was making decisions they felt should be made by highway engineers, resigned in protest.

In December 1981, California state senator Paul Carpenter, a particularly vehement adversary of Gianturco’s, held a series of hearings about the bridge, as well as about whether Gianturco had the authority to specify its width. He called Gianturco to speak at one of these hearings. Gianturco and her husband, John Saltonstall, were preparing to travel back to Massachusetts to visit family, and she asked the hearing to be postponed. Instead, Carpenter had a court issue Gianturco a subpoena.

Saltonstall went to the East Coast alone. While there, he was involved in a head-on auto collision. Defying the subpoena, Gianturco left to visit him in the hospital. Carpenter and others held the meeting in her absence. A few Caltrans engineers in the audience mocked her by saying things such as, “She got what she deserved.”

The state Assembly Committee on Transportation, led by Assemblywoman Marian La Folette, began an investigation. Gianturco, citing the fact there had been no accidents on the bridge, asserted that she was legally allowed to make a decision on the width of the bridge. At the conclusion of the investigation in December, the state auditor general supported her authority regarding the bridge. A thirty-two-foot-wide bridge was built in 1994.

Public officials and the general populace alike ridiculed her, calling her “the ice-plant lady” (because of her interest in landscaping the freeways) and “Giant Turkey” (a play on her name). But Gianturco continued to defend her positions on freeway construction and mass transit. Although extensive development of a rail transit system in Los Angeles remained elusive (voters turned down a proposed tax to fund mass transit in June 1976), Caltrans funding expanded Amtrak service between Los Angeles and San Diego from three to five daily round trips. In October 1982, Caltrans funded a commuter train between Oxnard and Los Angeles. The train, heavily opposed by the Southern Pacific Railroad, failed to attract many passengers and was canceled in March 1983.

DEUKMEJIAN AND TROMBATORE

In November 1982, George Deukmejian was elected governor. Upon taking office in January 1983, he announced that he would direct additional funds to the highway system. In his State of the State speech, he said, “Our transportation infrastructure has badly deteriorated over the past eight years. My budget establishes priorities which shift the emphasis from exotic alternative transportation schemes over to the proven priorities of safe, well-maintained, and efficient highways.” He replaced Gianturco as director of Caltrans by appointing Leo Trombatore, a highway engineer.

Under Trombatore, Caltrans built seven hundred miles of new freeways throughout the state. However, the big freeway-building boom of the ’50s and ’60s was a thing of the past. The anti-tax mood of the California populace had culminated in the adoption of Proposition 13 in June 1978, limiting available funding.

EPILOGUE

After leaving Caltrans, Gianturco spent most of her time lecturing at universities and transportation conferences, writing newspaper articles and caring for her elderly parents. She is currently serving on the board of directors of the Sacramento chapter of the ACLU.

Caltrans has had eight directors, including one woman, since Trombatore resigned in 1987. Although all struggled with changing transportation priorities and limited funds, none has been the lightning rod that was Gianturco.

When Jerry Brown became governor again on January 3, 2011, some speculated that he would reappoint Gianturco as director of Caltrans. But Malcolm Dougherty, a Caltrans veteran of more than twenty years, remained in the position.

At a transportation conference in 1994, Jerry Baxter, a Caltrans official, quipped that the Diamond Lane “may have set back HOV development in California ten years.” While other parts of California, such as San Diego and San Francisco Bay Area, continued to develop and expand carpool lanes, development in Los Angeles and Orange Counties languished until 1985, when a carpool lane was added on the eastbound Artesia Freeway (SR-91). Unlike the 1976 project, this was an entirely new lane, created from the shoulder nearest the center median. Caltrans avoided the term “Diamond Lane” in its marketing materials, preferring to call the facility a “carpool lane” or an “HOV lane.” Carpool lanes were shortly added to other freeways; by 2014, 950 miles of carpool lanes were available on Los Angeles County freeways.

Although there have been a few complaints from drivers unable or unwilling to carpool, most of the driving public seemed to accept the lanes because they were not created by taking a freeway lane from general use. When the Northridge Earthquake damaged the Santa Monica Freeway on January 17, 1994, Caltrans closed much of the usable part of the freeway to all traffic except buses and carpools, effectively reinstating the Diamond Lane with little opposition. Despite calls to make the carpool lane permanent, all lanes of the freeway were opened to general traffic when repairs were completed.

As of late 2012, HOV lanes on the Harbor (I-110) and San Bernardino (I-10) freeways are available to those who drive alone—for a price. The new Metro ExpressLanes allow access to single-occupant vehicles, equipped with transponders, for a fee. Carpools still use the lanes for free, although their vehicles now must also have transponders.

After her tumultuous directorship, Gianturco feels vindicated by renewed expansion of the carpool lane network and new rail transit systems that have developed since 1990. “All that stuff we talked about years ago is the stuff that’s finally happening now,” she said in a February 1994 Los Angeles Times article. “Carpool lanes, the Metrolink, the idea of using existing rail lines are all programs that we started way back then.”