CHAPTER 14

MOVING TOWARD METROLINK

The Oxnard–Los Angeles CalTrain

Since October 1992, Metrolink commuter trains have operated throughout Southern California. Each weekday, nearly forty-four thousand passengers board trains at one of the system’s fifty-five stations and enjoy a traffic-free commute to work, to school or for pleasure travel.

The path to Metrolink, however, has been rough. While Southern California has always had plenty of railroad tracks, efforts to develop commuter rail met with resistance and hostility from both railroad companies and certain politicians until the early 1990s.

THE FIRST COMMUTER RAILROADS

As railroads connected cities across the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an important market was short-distance passenger trips between a large city and its suburbs. The railroads, to avoid overcrowding on the long-distance routes, offered additional trains called commuted (“cut short”) trains. Passengers who rode them became known as “commuters.”

However, in Southern California, because Pacific Electric’s Red Cars performed most of this function, the mainline railroads provided few trips specifically for commuters.

After World War II, the railroads, facing competition from automobiles and airlines, discontinued passenger trains by the hundreds and focused on their highly profitable freight business.

By the early 1970s, concerns about the nation’s disappearing passenger trains led the U.S. government to create the National Rail Passenger Corporation (Amtrak), to preserve and operate what was left of the nation’s passenger rail network. However, the law that formed Amtrak prohibited it from operating commuter service. Local jurisdictions had to contract with the railroads in order to preserve commuter trains.

BAXTER WARD

As Southern California entered the 1970s, traffic congestion, air pollution and gasoline shortages heightened interest in commuter rail. In November 1972, voters elected Baxter Ward, a television news commentator, to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors.

A longtime train enthusiast and public transit advocate, Ward felt strongly that a rail transit system in Southern California would lessen traffic congestion, reduce air pollution and prepare the region for gasoline shortages. Primarily interested in a rapid transit system with its own right-of-ways, he also supported passenger trains using existing trackage to carry commuters from the suburbs into downtown Los Angeles.

Southern Pacific, Union Pacific and Santa Fe, the major railroads owning most of the trackage in Southern California, were not supportive of commuter trains. Fearing interference to their lucrative freight business, they vigorously resisted any passenger train service other than the Amtrak trains they were legally required to accommodate.

In 1973, the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) commissioned a study recommending two commuter rail trips between Oxnard and Los Angeles. In December 1974, the County of Los Angeles filed a request with the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to enable commuter trains to use the Southern Pacific Coast Mainline across the San Fernando Valley and into Ventura County.

This was a single-track railroad with several sidings, requiring trains going in opposite directions be carefully scheduled. Amtrak’s daily Coast Starlight was the sole passenger train. Major industries served included General Motors and Anheuser-Busch in Van Nuys, Lockheed in Burbank and several lumberyards and other businesses. Southern Pacific and representatives of the businesses along the rail line expressed concerns about the disruption to freight service the commuter trains would supposedly cause.

Baxter Ward. Terry Guy photo collection.

BAXTER WARD’S “CHOO CHOO”

Despite the railroads’ resistance and the opposition of fellow supervisors Peter Schabarum and James Hayes, Ward convinced supervisors Kenneth Hahn and Edward Edelman to vote to acquire eight 1940s-era passenger rail cars from an Oregon tourist railroad. On a three-to-two vote, the board of supervisors allocated $230,000 to purchase the cars and $1.8 million to refurbish them.

Ward named the train “El Camino” and planned to use it for commuter service on the Santa Fe Railroad between Orange County and Los Angeles Union Station. Unlike the three existing Amtrak round trips, the El Camino’s schedule would be convenient for people working in downtown Los Angeles.

Santa Fe was unwilling to operate the El Camino or provide any support. While Amtrak was willing to run the train, it still was legally prohibited from running trips specifically for commuters. Amtrak agreed to operate the train as an additional Los Angeles–San Diego run, on a six-month trial basis. Los Angeles County and the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) provided funding. No commuter-specific features, such as reduced fares or monthly passes, would be offered.

Schabarum and Hayes, along with other Los Angeles County officials, remained unimpressed with the idea, citing the millions already “wasted” on an antiquated train that had not moved in years. They called the train “Baxter Ward’s Choo-Choo,” “Baxter’s Folly” and the “Train to Nowhere.” But Ward insisted that the El Camino would run at least 80 percent full.

The first train left San Diego on February 14, 1978. Ward and Caltrans director Adriana Gianturco were on board. Each station featured a festive opening day ceremony. Various government officials, including Governor Jerry Brown, made speeches and then boarded the train. About three hundred passengers rode the El Camino into Los Angeles.

Regular ridership, however, only totaled about one hundred. Four significant problems existed. Upon arrival in Los Angeles, most passengers were some distance away from their jobs, requiring a bus or taxi ride. Many commuters found the El Camino’s return run at 4:30 p.m. too early and used Amtrak’s regular 5:30 p.m. trip instead, reducing El Camino ridership. The trains often ran late. Ward accused Santa Fe of “sabotaging” the commuter service by scheduling track construction projects. Santa Fe and Amtrak countered that bad weather, which damaged the tracks, was ultimately to blame for poor on-time performance.

August 12 marked the end of the trial but not the train. Amtrak, with financial support from Caltrans, added a new San Diegan train, using Amtrak equipment, on El Camino’s former schedule. This marked the beginning of Amtrak and Caltrans working together to provide additional service on what would eventually become Amtrak’s second-busiest route.

STRANDED IN SIMI VALLEY

The city of Simi Valley, on the Southern Pacific mainline to Ventura, was another supporter of commuter rail. During the 1970s, its population had grown from seven thousand to seventy thousand residents. The Simi Valley Freeway (SR-118) was still incomplete, so residents used surface streets to reach the San Fernando Valley and Los Angeles. “We’re stranded. We don’t have a freeway straight through. Yet seventy-five percent of our workforce commutes to Los Angeles,” remarked Mike Sedell, an assistant to the city manager.

At an August 1979 CPUC hearing, after Southern Pacific representatives expressed their opposition to the commuter rail, Ward responded that the railroad was “psychologically against” passenger trains. “You cannot tell me that a railroad cannot schedule two trains in and two trains out without blowing up the San Fernando Valley,” he said.

On June 4, 1980, CPUC ordered Southern Pacific to provide the commuter rail service. But in response to Southern Pacific’s concerns, CPUC agreed in September to hear more testimony regarding commuter strain scheduling and interference with freight.

ANTONOVICH TAKES OVER

In late 1980, former state assemblyman Michael Antonovich, who opposed both the El Camino and the Oxnard–Los Angeles commuter rail projects, ran against Ward. During his campaign, Antonovich’s television commercials showed a toy train and mocked Ward’s “Train to Nowhere.” On November 4, Antonovich won the supervisor’s seat.

In his last days in office, Ward, by making an agreement with Caltrans to use the train on the Oxnard commuter service, temporarily prevented the county from disposing of it. However, once Antonovich assumed power, he, along with Schabarum and newly elected supervisor Deane Dana, rescinded the agreement. The El Camino remained in storage until 1985, when a tourist railway paid $365,000 and moved it to Mexico for use in Copper Canyon.

The new board of supervisors withdrew funding from the Oxnard–Los Angeles project, leaving only Caltrans and Simi Valley in support. “I don’t know why L.A. County opposes it. L.A. can’t possibly want Simi Valley’s traffic on its streets any more than our traffic wants to be there,” remarked Simi Valley mayor Elton Gallegly.

SP AND CPUC

The battle between Southern Pacific and Caltrans continued in the courts. When a lower court refused to overturn CPUC’s decision, Southern Pacific appealed the decision to the California Supreme Court, only to lose again in December 1980. On April 7, 1981, CPUC reaffirmed its previous order for Southern Pacific to start commuter train operations and called for both Caltrans and Southern Pacific to execute a contract for the service within 180 days.

Finally, in June 1982, CPUC ordered Southern Pacific to start the service on October 18. The railroad was to immediately start building passenger facilities and setting fares and timetables.

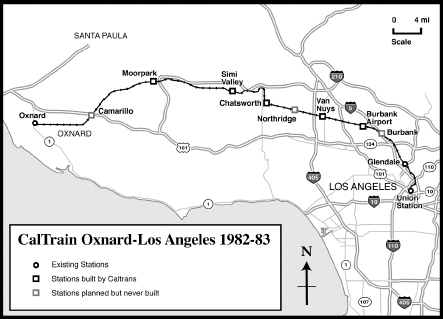

The California Transportation Commission allocated $6 million in state transportation funds for the commuter rail service, with $100,000 available for immediate use. Caltrans called the new train “CalTrain,” the same name given to the San Francisco–San Jose commuter rail when the state agency took over that service from Southern Pacific in 1980.

On opening day, three hundred passengers, mostly politicians, other city officials and railfans, boarded the first train. Only thirty-eight people were actual commuters. The train only stopped at Oxnard, Simi Valley, Van Nuys and Glendale; other stations were not yet ready. The Oxnard station had no parking, advertising and marketing were minimal and the first train was delayed so that Caltrans director Adriana Gianturco could christen it with a bottle of champagne.

But she was confident that the low inaugural ridership was only a minor setback. “Even we didn’t know for sure that the train was going to run until the last minute. That hurt us because people don’t plan on using public transportation unless they know what they are getting. In addition to that, of course, any new service takes time to build up a ridership. People just aren’t used to it yet.”

The passengers seemed happy on board. “I’d rather ride this than drive any day,” said one commuter from Oxnard. Another quipped, “Let’s thumb our noses at those poor guys on the freeway” as the train passed near a crowded road. Some passengers griped about the fares (eleven dollars round trip from Oxnard); others complained about the lack of connecting bus service. But most agreed that the train was a much nicer alternative to being stuck in freeway traffic or a transit bus making many stops on its way downtown.

Ridership increased as more people found out about CalTrain through advertisements but leveled off at about 300 per day, far below the 1,400 predicted by Caltrans. Once stations at Camarillo, Moorpark, Chatsworth, Northridge, Burbank Airport and downtown Burbank opened, ridership would increase to 2,600, Caltrans officials promised.

CalTrain map. Author’s collection/Mapcraft.

CalTrain used Amtrak coaches until Amtrak needed them for the holiday travel season. Caltrans then borrowed several double-decker commuter cars from Chicago’s Regional Transportation Agency (RTA). These cars also allowed faster passenger loading and unloading.

DEUKMEJIAN AND DERAILMENT

On November 7, 1982, California voters elected George Deukmejian as governor. Deukmejian regarded commuter rail as an “exotic” mode of transportation and promised to redirect transportation funding to highways.

On November 26, debris on the track punctured a locomotive’s fuel tank as it was returning from Los Angeles. The train limped to Simi Valley, where passengers boarded Oxnard-bound buses.

Caltrain. Terry Guy photo collection.

That same day, Southern Pacific announced that it was idling all General Electric P30 locomotives, including CalTrain’s, because one had derailed in Texas. The railroad offered General Motors GP9 locomotives as replacements. Since these were incompatible with the RTA cars, Caltrans returned that equipment to Chicago and obtained compatible cars from the Bay Area CalTrain. However, the maintenance personnel in Los Angeles were unfamiliar with the CalTrain cars, requiring them to be sent back to San Francisco for any major maintenance. Also, the cars’ air-conditioning systems, designed for the Bay Area’s mild weather, performed poorly in Southern California’s warmer temperatures. Trains often ran with as few as one or two cars.

Although Gianturco, a Brown appointee, knew that her days were numbered under Deukmejian, her enthusiasm for CalTrain was unabated. She presided over the opening of the Chatsworth CalTrain station on December 29. As Amtrak’s Coast Starlight thundered by, she stated, “[CalTrain] is doing exceptionally well, and its future looks bright. The fact that this service has shown a steady growth in ridership—doubling since late October—is a positive omen for its future success.” In fact, the ridership had not doubled; it had only risen by 50 percent, still far below Caltrans’s original predictions.

Once in office, Deukmejian kept his promise and zeroed out CalTrain from the state budget. Without funding, CalTrain service would end on June 30, 1983. In addition, Southern Pacific claimed that it was entitled to $588,000 per month to operate the trains; Caltrans was willing to pay only $70,000. Because of uncertain funding, Caltrans scrapped plans for stations at Northridge, Camarillo and Burbank; Burbank Airport and Moorpark stations opened in mid-January.

KREBS: TAXIS ARE CHEAPER

On Friday, February 4, passengers boarding CalTrain at Union Station received a flyer announcing that Southern Pacific was immediately discontinuing the commuter service. In a press release issued that day, Southern Pacific president Robert D. Krebs stated, “This experiment has been bad for the taxpayers of California, bad for the industries served along our line, and bad for Southern Pacific. While each individual commuter pays only a few dollars per round trip, the state’s taxpayers are contributing about $170 for each commuter each day.” He concluded, “It would be far cheaper for the State to give each CalTrain commuter a brand new car or a taxi ride to and from work each day absolutely free.”

The next Monday, a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order forcing the railroad to resume CalTrain and purchase newspaper advertisements stating that the service had restarted. The trains, which had been moved to San Francisco for maintenance, rolled again on Wednesday.

On February 11, CPUC subpoenaed Krebs and several Southern Pacific officials, ordering them to attend contempt-of-Commission proceedings against the railroad. Southern Pacific officials insisted that the Staggers Rail Act of 1980 ended CPUC jurisdiction over railroads providing interstate service. The Commission fined Southern Pacific $16,000—$2,000 for each train that did not run on February 7 and 8. “We wanted to put [Southern Pacific] on notice that it can’t decide on its own when it will or will not run a service,” said CPUC executive director Joseph Bodovitz.

THE END OF CALTRAIN

Although riders expressed their support, CalTrain was losing friends in Sacramento. On February 15, Caltrans called for a temporary suspension of CalTrain until the subsidy dispute could be settled. About a week later, the California Transportation Commission (CTC) voted to recommend the legislature stop funding CalTrain, due to the low ridership and poor timekeeping.

Train supporters criticized Governor Deukmejian for not properly supporting CalTrain, calling to attention a $12,200 donation by Southern Pacific to his 1982 gubernatorial campaign.

During a series of CPUC hearings in late February, Warren Weber, Caltrans’s director of rail projects, described Southern Pacific’s operation of CalTrain as a “carnival road show.” He continued, “If I were a commuter, I wouldn’t buy a monthly pass because I don’t know if it will run tomorrow,” and he criticized Southern Pacific for late trains and non-uniformed conductors.

Nature’s voice was heard when a powerful storm on March 2 washed away a railroad bridge near Moorpark. All rail service was halted until the bridge was repaired several days later.

Finally, on March 11, CPUC voted to suspend CalTrain indefinitely, while requiring Southern Pacific to retain the passenger facilities Caltrans had already built, in case service restarted. Although Caltrans officials thought that CalTrain might roll again one day, other supporters were not so sure. Douglas Ring, a former legal assistant to Baxter Ward, stated, “I do not see it being reinstituted under the [Deukmejian] administration, even if the tariff question is resolved. The administration came out against the train the day after [Deukmejian] was inaugurated, and I can only presume they made that decision without evaluating the service.” On September 29, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reaffirmed CPUC’s jurisdiction over Southern Pacific.

In April 1985, the Interstate Commerce Commission ruled that Southern Pacific could determine the cost of running CalTrain; since the railroad desired much more than Caltrans wanted to pay, the CalTrain service never resumed. By September, Caltrans and Southern Pacific had arrived at a settlement for past costs, including lease payments for stations built on rights-of-way.

MOVING TOWARD METROLINK

Although CalTrain was officially dead, commuter rail remained alive in the minds of transit officials. In September 1987, California state senator Alan Robbins, along with officials from Burbank and Simi Valley, advocated commuter rail through the San Fernando Valley be provided during an upcoming, four-year-long construction project on the Ventura Freeway.

By 1990, Amtrak’s San Diegan, with support from Caltrans, provided eight daily round trips between San Diego and Los Angeles, plus two round trips to Santa Barbara. The earliest northbound train arrived at Los Angeles by 7:55 a.m.—early enough for commuters whose workday started around 8:30 or 9:00 a.m. A cadre of commuters, mostly higher-paid employees who could afford fares totaling $352 per month, rode this train to work each day. Changes in the laws governing Amtrak allowed it to operate locally funded commuter trains. In May 1990, Orange County paid Amtrak to operate the “Orange County Commuter,” one additional round trip between San Juan Capistrano in Los Angeles. This train arrived in Los Angeles at 7:30 a.m., leaving workers plenty of time to take buses or shuttles to their jobs. Fares were also lower than on regular San Diegan trains.

Commuter rail planning remained a county-by-county effort until several key events in 1990. Former rail transit opponent Governor Deukmejian signed State Senate Bill 1402 in May 1990. This bill directed the transportation commissions of Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura Counties to develop a unified commuter rail plan. Southern Pacific, another former nemesis of commuter rail, sold 177 miles of right-of-way to the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (LACTC). Santa Fe and Union Pacific also sold certain stretches of track and provided access rights to others. Statewide transportation bond measures and countywide half-cent sales taxes approved by voters funded track improvements, new stations and rolling stock.

Metrolink train. Author’s collection.

In response to SB 1402, the transportation commissions formed the Southern California Regional Rail Authority, or Metrolink, in June 1991. When the first Metrolink trains rolled from Pomona, Santa Clarita and Moorpark into Los Angeles Union Station on October 26, 1992, five thousand people boarded for fare-free rides that day. In 1993, Metrolink extended service to Riverside and San Bernardino and replaced the Orange County Commuter’s single round trip with three.

After the January 17, 1994 Northridge Earthquake damaged several Southern California freeways, Metrolink, using federal emergency funds, extended service to the Antelope Valley and Camarillo. Ridership, which was normally about 9,500 daily boardings, spiked to 31,000, with the line to Lancaster alone carrying 22,000 daily boardings. Ridership dropped as the freeways reopened but has increased to about 40,000 as of 2014.

Metrolink has experienced serious problems. Passengers have complained of high fares (Metrolink fares are generally two to three times higher than the corresponding express bus fare), while taxpayer groups have complained of high subsidies (about 40 percent of revenues come from fares, with local transportation funds covering the remainder). And several accidents, including multi-fatality collisions in Glendale in 2005 and Chatsworth in 2008, have raised serious concerns about the system’s safety.

But Metrolink has responded by developing new coaches with safety features and endeavoring to keep fares as low as possible, ensuring that commuter rail will remain a permanent fixture of Southern California’s transportation landscape.