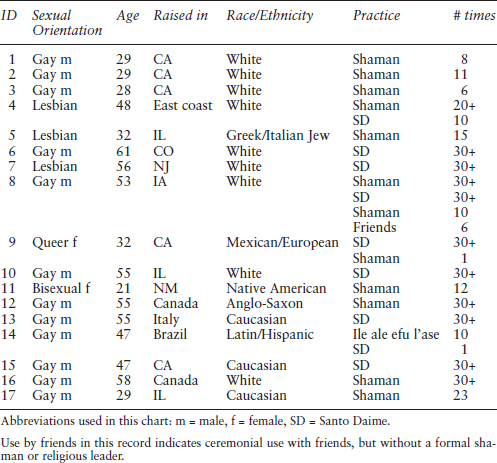

Table 7.1 Demographic Table of Study Participants

I first published my dissertation on ayahuasca’s influences on gay and lesbian experiences of identity4 in 2011 (Cavnar, 2011), having collected most of the interviews in 2008 and 2009. Since then, much has changed in regard to both ayahuasca and gay rights. Gay marriage was legalized in the United States and conversion therapy to alter sexual orientation has been banned in California, Vermont, New Jersey, Illinois, Oregon, and the District of Columbia. Statistical trends indicate a growing acceptance of gay people in general, with younger people showing less bias against gay people in an accelerating trend (University of Virginia, 2015).

In a parallel fashion, ayahuasca has also become more familiar and accepted, though to a much smaller degree than the acceptance of gay rights. Research is expanding internationally (Bouso, 2012); television programs and movies have included it in their storylines; celebrities increasingly report on their insights during rituals; people sell retreats online; and retreats are held throughout the US and the world with traveling or local shamans or facilitators leading them. Ayahuasca is much more popular now than when I first began my research and had to persevere to find individuals who had even heard of it. In Brazil, I have recently learned there is a transgender woman who is a fardada (member of the church of Santo Daime), accepted to participate in the women’s sections of the ritual. Much has changed; therefore, my research contributes a significant study of ayahuasca and sexuality in a period marked by increasing visibility and awareness of these elements in our culture. Here, I present my past research and commentary that came with change, time and greater rumination.

When I first presented the idea of examining the influences of ayahuasca on gay identity to some ayahuasca researchers and practitioners, I was met with a quizzical response; what had the two to do with each other, ayahuasca and being gay? As a lesbian, I knew that the positive shift in my identity that occurred when I saw my own divine identity under the effects of ayahuasca was critically germane to questions of self-worth that often plague other members of sexual minorities, especially as expressed in spiritual contexts; for me, the connection seemed obvious.

The psychoactive brew ayahuasca has been investigated in several studies and shown to have positive long-term effects on mental states (Fábregas et al., 2010), and a particularly strong positive effect on perceptions of identity (Shanon, 2002). My research explored the experience of gay people who drink ayahuasca, and examined the influences that it has on gay identities and its intersections with spiritual experiences. The qualitative study in this chapter is based on the responses of 17 self-identified gay and lesbian participants who had taken ayahuasca in a ceremonial context within three years. They were interviewed regarding their self-perceptions and integration of group beliefs. Participants drank either in shamanic or Santo Daime ceremonies, or in the case of one participant, with an Afro-Brazilian group that used ayahuasca. The results of this study show all participants reporting affirmation of their sexual orientation, and none reporting negative effects on perception of identity. Benefits in other domains, attributed to ayahuasca sessions, contributed to the positive outcomes that were reported by this group.

Ayahuasca, a psychoactive brew made most commonly from a combination of an Amazonian vine (Banisteriopsis caapi) and leaves of a bush (Psychotria viridis), is reported to incite religious and spiritual insight in those who drink it. The use of ayahuasca for personal exploration, physical and emotional healing, and religious practice has grown recently both in the United States and worldwide, expanding from its traditional roots in South America to become a global phenomenon (Labate & Cavnar, 2011; Labate & Jungaberle, 2011; Fotiou, 2010Labate & Cavnar, 2014.)

In 2008 an estimated 20,000 people were drinking ayahuasca throughout the world (Labate, Santana & Santos, 2008); in 2015, 80,000 ayahuasca tourists were estimated to have visited Iquitos alone (Dube, 2016). People drink ayahuasca in several contexts throughout the world, either as ayahuasca tourists in South America, with traveling shamans in their own countries, or as adherents of the two international ayahuasca churches, Santo Daime and União de Vegetal (UDV), and their numerous offshoots and variations. Ayahuasca is usually consumed safely, and there is no risk of overdose. However, cases have been reported of different plants being added to the admixture, such as toé (Brugmansia) or lack of supervision of intoxicated participants leading to injuries or deaths (Santos, 2013a, b). Originally used by indigenous people in the Amazon for hunting, healing, sorcery, and communication with the spirit world, ayahuasca is said to heal physical and psychological wounds and to inspire religious and spiritual visions. The experiences of people who drink ayahuasca are often life changing, with many reporting cures for drug addiction (Labate, Santos, Anderson, Mercante, & Barbosa, 2010; Mabit, 1996; Labate & Cavnar, 2013) and depression (Anderson, 2012; Palladino, 2009; Sulla, 2005), post-traumatic stress disorder (Nielson & Megler, 2013), as well as a variety of physical illnesses (Schmid, Jungaberle & Verres, 2010).

Intense emotions and experiences in which participants may feel they are dying or changing form are common in ayahuasca sessions, but these are also viewed as part of the healing process. Ayahuasca produces psychological effects that may affect the drinker’s perceptions of identity, origin, or purpose (Shanon, 2010) and can change the way they view the world and themselves even after the ceremonies are concluded (Trichter, 2009; Barbosa, Cazorla, Giglio, & Strassman, 2009; Barbosa, Giglio & Dalgalarrondo, 2005).

One notable attribute of the experiences reported by non-indigenous ayahuasca drinkers has been its effect on the perception of identity: drinkers have reported seeing themselves in ways much different than they do in their ordinary lives, understanding patterns of behavior and addictions, as well as gaining insight into relationships with others and with their own conceptions of themselves (Kjellgren, Eriksson & Norlander, 2009). Followers of shamans and the ayahuasca religions report life-changing insights given by the drink that cause them to make fundamental changes in their daily lives outside the ceremonies. The idea of shamanic initiation involves the destruction of one identity and the creation of another (Lewis, 2008). These experiences are of great importance to many people, but may have a particular value for gays and lesbians.

Sexual minorities are often told that part of their essential identity is flawed or sinful, and such perceptions can lead to personal crisis that can result in self-destructive behavior, including addictions, depression, and suicide (Comstock, 1996; Haas et al., 2011; Hattie & Beagan, 2013). The management of identity by sexual minorities can stimulate various ways of expressing or suppressing its public and private aspects. Social identities and personal identities interact in gay individuals in strategic ways to avoid or invite conflict vis-à-vis the dominant culture (Cox & Gallois, 1996). The powerful experience of ayahuasca ritual participation seems to allow for the examination of identity and the evolution of self-concept. The research question driving the study reported in this paper was: In what ways do cultural forces get integrated, rejected or reinterpreted in the process of identity transformation during and after ayahuasca rituals and what visions and insights are provided to form or reconfirm general and sexual identities?

Psychedelic research was suppressed for several decades following the placement of psychedelics in 1970 into Schedule 1, among the most severely dangerous substances without medical value. Research has recently started up again (Kelly, 2008) as exploration of MDMA as a treatment (Amoroso & Workman, 2016) and studies of psilocybin (Grob et al., 2011; Howland, 2016) for various mental health conditions have been granted with promising results. Since homosexuality is no longer considered a mental illness, there will not be treatments or any legitimate research exploring the capacity of psychedelics to alter sexual orientation. Although sexuality is a significant motivator for social identity, the effects of gender and sexual orientation on outcomes in psychedelic research has rarely been considered (Tolbert, 2003).

One early use of psychedelics by psychologists was in conversion therapy. “Conversion therapy,” or “reparative therapy,” is the name for therapy that attempts to change the sexual orientation of homosexuals. This type of therapy became more controversial after the removal of homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1973 (Drescher & Zucker, 2006). The opinion of the APA today is that there are no safe or effective ways of changing someone’s sexual orientation, and therapies that claim to do so can reinforce negative views of homosexuality and be harmful to the client (APA, 2008).

There are a few mentions of psychedelic therapy for gay people, focusing on “healing” homosexuality. Masters and Houston (1966) reported giving the psychoactive cactus peyote (Lophophora williamsii) to a self-identified gay male volunteer in The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience. They said that the participant displayed more heterosexual behavior and a greater desire to appreciate his appearance after the peyote experience. When writing about work they did with the 14 homosexual men they experimented with, they spoke of their subjects’ passivity being transformed by psychedelic therapy, and attributed a deepening of the voice, greater vigor, improved posture, and greater masculinity to treatment with LSD. A study by Martin (1962) looked at the effects of LSD on 12 gay men. Martin recommended LSD as a treatment for homosexuality. Administering many low doses in a treatment known in the past as “psycholytic therapy” (Leuner, 1993), and currently referred to as “microdosing” (Orion, 2015), and encouraging intense mother-transference, Martin claimed that seven out of 12 achieved heterosexual orientation with only one “slight relapse” in a three- to six-year follow-up (Sandison, 2001).

Stafford and Golightly (1967) reported on LSD therapy to treat homosexuality during the 1960s. They found that homosexual issues were often resolved using psychedelic therapy and that homosexuals would either be at peace with their orientation after LSD therapy or decide that they were really heterosexual. Stafford and Golightly viewed homosexuality as the result of early childhood trauma and “morbid dependency” on parents, both of which could be treated with regressive “shock therapy” using LSD. Shocking the system, using LSD, and further “dynamiting” it with psychodrama, marathons, and “vegetotherapy” was thought to break a dam in the psyche that could open the way to healing. Stafford and Golightly (1967) recommended that LSD be used to treat transvestism, fetishism, and sadomasochism in the same way that it could be used to treat homosexuality. In a paradoxical tribute to LSD’s effect on identity in gay people, they state, “It would appear, however, that LSD is successful in homosexual problems because it can … alter an individual’s inappropriate and/or pejorative total self image and lead to self acceptance” (“Everyday Problems” part 1). This perspective reflects the thinking current in the late 1960s, in which homosexuality was viewed as a mental disease, related to paraphilias (Suppe, 1984).

Grof (2000) treated homosexual clients with LSD. He came to the conclusion that gay men’s dislike of sex with women was related to images of “vagina dentate” and castration fantasies that could be envisioned during LSD sessions, an idea originating with Freud. He related lesbianism to the desire to be close to the mother. Grof said that he had treated mostly homosexuals who were dissatisfied with their orientation, and that a healthy adjustment to same-sex orientation was possible and may not represent intra-psychic struggle. A study by Alpert (1969) was one of the earliest reports in the literature on sexual minority experience with psychedelics. Alpert administered 200 micrograms of LSD to a male self-identified bisexual volunteer who was dissatisfied with his attraction to men. During his fifteen-hour trip, the subject was shown pictures of women and encouraged to develop feelings toward them. In subsequent LSD sessions, a woman whom the man knew was present and he had sexual intercourse with her. One year after the treatment, Alpert reported that the man was living with a woman, but had had two subsequent homosexual encounters, which the subject described as tests of himself to see if the changes he had experienced as a result of the treatment were “real.” Alpert explained that the use of LSD allowed the subject to take a broader view of the archetype of “woman” and find connections to primal desires within the archetype, which he could then generalize to all women.

After the cessation of psychedelic research at the end of the 60s, most of the therapy that continued to be conducted with psychedelics in Europe remained unpublished (Williams, 1999). As psychedelic research nearly died out after the 1960s, it appears that these treatments did as well (Snelders & Kaplan, 2002).

Several personal reports of individual experiences can be found in the literature on psychedelics and sexual minorities. The great majority of reports concern positive experiences, reflecting either that bad experiences were few or that bad experiences were seldom recorded due to an aversion to describing, remembering or being associated with them. First-person stories about psychedelic experiences by gays and other sexual minorities tend to reveal the positive rather than the negative effects psychedelics can have on gay people outside the laboratory or clinic. One early instance of a public report of psychedelic experience by a gay man was the testimony of the poet Allen Ginsberg, who wrote some of the first literature on ayahuasca use by Westerners in his book The Yagé Letters (Burroughs & Ginsberg, 1963). He had varying experiences with ayahuasca in South America, not all of which were enjoyable. When addressing a Congressional subcommittee on the use of LSD and marijuana on college campuses in 1966, he advocated the use of LSD for personal and social transformation. In his testimony, he described feeling closer to women as the result of his experiences with peyote (Ginsberg, 1966).

A report made by a “post-op” transgender woman (Denny, 2006) described her most recent experience using LSD. She and a “pre-op” transgender woman decided to take LSD and, at the peak of their experience, they agreed they would look at themselves naked, side by side in a full length mirror: “We would look to see whether we were monsters or whether we were God’s beautiful creatures. And through the wide open doors of perception, we saw the truth: We were beautiful” (Denny, 2006, p. 63). Berkowitz (2008), a lesbian, wrote about encountering her grandmothers in a vision during an ayahuasca experience on her 30th birthday. She concluded her report by saying that, due to her experience with the substance, she felt she had “reclaimed [her] life.”

In a more recent report, on Reset.me, a website that discusses psychedelic experiences, another transgendered person posted her account of gender confusion that was cleared up by taking ayahuasca. In the comments section to her post, someone else wrote that he had considered transitioning to the female gender, but, after drinking ayahuasca, decided it was the wrong course for him; he recommended that anyone thinking of transitioning drink ayahuasca before making any irreversible decisions (Greenham, 2015).

Sprinkle (2002), a bisexual sex worker, educator, and performer, wrote about her experiences with psychedelics and other drugs. She had not tried ayahuasca, but had taken “pharmahuasca,” a combination of chemical and natural sources that attempts to mimic the effects of the mixture of Banisteriopsis caapi and Psychotria viridis. She concluded that psychedelics could have a role in sex therapy because they can help individuals gain a fresh perspective on their identity because sexuality and the use of psychedelics are both about consciousness and self-discovery.

A gay author, Young (2003), described a trip to Peru with two other HIV+ men to drink ayahuasca with a renowned shaman. He recounted how each man with HIV came to the same conclusion in their visions: that the virus needed them to live off of, and that, using this information, they could negotiate a relationship where both the virus and its carrier would be able to survive.

Seventeen participants who had used ayahuasca with at least one other person in the past three years, in either or both shamanic and church settings, were asked a series of open-ended questions in interviews. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The results were coded according to research questions. Differences were sought in relationship to the setting and group beliefs, as well as in relationship to the drinkers’ own acceptance of their sexual orientation and how they felt they fit in with others in their ayahuasca-drinking circle. All of the participants were either current or past long-time residents of North America. Besides shamanic circle participants, only participants from Santo Daime, and one participant from an Afro-Brazilian religious group that uses ayahuasca, were interviewed. The UDV declined participation in this research. The UDV has made an internal formal statement regarding the undesirability of homosexuality and gay marriage that was not publicly disseminated, but was read at sessions for a time, though currently this has stopped (Monteiro de Souza et al., 2008).

Participants were recruited, beginning in 2009, by posting on Internet message boards and newsletters related to ayahuasca. There was some snowball sampling as participants referred some friends who qualified and were interested. A sociodemographic questionnaire was administered prior to the interview. This questionnaire collected data on age, location, religious background, previous use of drugs, and other data that helped contextualize responses. Participants were assigned code numbers instead of names to help ensure anonymity.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with each participant, using open-ended questions, allowing for follow-up questions as needed for elaboration and clarification. The interviews, lasting from 45 minutes to an hour and a half, were recorded and transcribed. The interview began with this question; “Tell me about any experiences with ayahuasca or within the ayahuasca community that caused you to reflect on your sexual orientation,” and continued to explore specific areas with questions such as, “Have your views about your sexual identity changed in any way as a result of using ayahuasca?”

Using qualitative content analysis, the data was coded for instances of similar meaning. By developing themes using content analyses that were grounded in empirical data and used to compare cases, it was possible to draw conclusions while remaining open to the variations in each individual’s narrative (Flick, 2002). Questions that were related to the focus of the study on issues of identity, including mentions of times that sexual orientation were salient during an ayahuasca experience, feelings of inclusion or separation, beliefs about future changes in acceptance of minority sexual orientation, and other instances of meaning that were developed as the data were coded.

In this study, 8 participants of the 17 drank with shamans, 3 drank both with shamans and the Santo Daime, 5 drank primarily with the Santo Daime, and 1 participant drank primarily with an Afro-Brazilian group called Ile ale efu l’ase. Twelve men and five women volunteered for the research (See Table 7.1). It is not known whether this imbalance in gender represents the gender breakdown of participants in the ayahuasca rituals studied; while it may, the exclusion of people who identified as “bisexual” tended to eliminate more women than men from the study, as more women than men identify as bisexual in general. (Diamond, 2000)

The two major styles of ayahuasca consumption studied here were the shamanic ritual and the Santo Daime works. The shamanic ceremonies the participants had attended were presided over by South American shamans or Western apprentices who had trained under them. Ayahuasca tourism is flourishing as North Americans and Europeans pay large sums to receive treatments and trainings from renowned shamans, both in South America and the US (Fotiou, 2010; Holman, 2011). Typically, in these contemporary ceremonies, the shaman drinks ayahuasca with the participants. However, traditionally, before the ayahuasca boom, the shaman would often be the only one who drank at a healing ritual. The participants then lie in hammocks or sit on mats on the ground while the shaman sings icaros, which are songs used to call spirits, guide visions, and heal. The shamanic ritual for Westerners is non-denominational; participation in shamanic ayahuasca rituals does not necessitate a belief in a god or knowledge of a theological system.

Santo Daime rituals, called “works,” are held at least twice a month, often more. Members of the church commit to attending, wearing uniforms, and singing and sometimes dancing continuously in ceremonies that at times can last up to 12 hours. The belief system is syncretic, combining Christianity with African and indigenous Amazonian beliefs.

One theme that emerged was of a re-definition of the self. Participants remarked on new understandings of themselves as “part of everything” or “part of God,” echoing statements made in previous literature on ayahuasca experiences (Kjellgren, Eriksson & Norlander, 2009; Shanon, 2002). Some saw themselves as divine beings with celestial parents, descended from the stars or having a mission on Earth to complete. As one lesbian woman who practiced with the Santo Daime described regarding her second experience with the tea:

I had a vision of flying to Earth from the Milky Way on my path of service here on Earth, and it was all connected to the plant medicine … I understood myself as a person from the stars … [I saw myself as] being a child of the divine mother and the eternal father. So the most fundamental level of my experience of being, and of my self, is completely different. Where before, I identified with being separate, being tortured, being tormented, being in pain.

The theme of self-acceptance was common, combined sometimes with the discovery by some respondents of the capacity to heal others, and for others, a connection to humanity that they had not felt before. One man said, “I’ve always felt I was from a different planet, growing up [fat, gay, and un-athletic]. Daime showed me I have a mission on Earth.”

Some participants made reference to the ego and duality and how ayahuasca helped them to understand the dynamics of perception of the self. Other participants noted a unifying effect, reaching back to their childhood identity or putting pieces of their lives back together. Ayahuasca was perceived by some as clearing away obstacles to true perceptions about the self or that it actively disclosed the true aspects of themselves to themselves. One man who drank with the Santo Daime said:

It brings me to a heightened consciousness that stays for days, sometimes weeks. All the junk comes back in at a certain point and you get kind of filled up with the smoke and mirrors of illusion. But then you come back to the medicine and you pierce through it again and it’s blown away. Blown out. And you reenter higher consciousness and who you truly are … I was able to see through my mask, my persona, my identity, and know that it was a mask, a persona, an adopted identity and that underneath it is the world; God is looking out with this mask on.

No participants reported negative effects on their perception of their sexual orientation as a result of drinking ayahuasca. For some, sexual orientation was not an issue in their ayahuasca experiences. One lesbian responded to questions about ayahuasca’s influence on her sexuality:

It [sexual orientation] was never, in all my journeys, actually, honestly I don’t think it’s ever come up … I think I’m definitely comfortable being a lesbian … Ayahuasca didn’t ever bring that up. But I think being deeper in touch with myself has definitely put me more in touch with my sexuality as well. So there’s definitely been a deepening there too.

One participant said ayahuasca rituals did not have any effect on his perception of his sexual orientation, but only of his sexual behaviors. A member of Santo Daime said she felt her ayahuasca practice enhanced her ability to integrate her sexual orientation into her own identity:

I am more liberated as I grow in my own ability to be in tune with my inner self. And to be honest about who I am and what I feel, and to even know what I am and what I feel helps me to live more congruently all the time. And so I think my spiritual life helps me to be a better queer.

One gay participant said that he felt that sexual orientation was not as important to him now, because these “labels fall away” as a result of ayahuasca experiences. Another man who practiced with the Santo Daime responded, “My identity has been altered in … that, it’s there and it isn’t there. Identification with being homosexual, or heterosexual and all that stuff; it’s just part of the game now. It’s not a do or die kind of situation.”

Ayahuasca drinking had an impact on perception of gender identity that was noted by some of the participants. Gender identity is the perception of what gender one is, which is a separate area of identity from sexual orientation, or whether one is gay or straight. One lesbian who drank with shamans said that she felt her gender identification became balanced and she was allowed to experience herself as a “two-spirited” person, in line with her Native American heritage, which recognizes and honors gay people and gives them a special place of honor in their culture. She said,

What I did notice was me opening up more to my feminine side because I was a very masculine woman. And I was very proud of that and very aware of that, almost to the point where I consciously overshadowed my feminine self. And, if anything, it brought me from being very, very, very gay in my own mind to sort of bringing me back a little bit in the center. It more balanced with my femininity and masculinity. Just working with plants, and the visions I had of leaves, and trees, it’s just a very feminine type of spirit. So I sort of found a greater value in femininity, and re-drew myself not as completely masculine, but as a balanced two-spirited, if you want to use the Lakota term, person.

Several participants commented on feeling self-acceptance and affirmation that their sexual orientation was “OK” or said that as they became more comfortable with themselves in general; they also became more comfortable with their sexual orientation. One woman reported, “My sexual orientation has gotten clearer and clearer. I used to think I could swing both ways, but now I don’t have any interest in the opposite sex at all, and I am very accepting of that.” A male shamanic practitioner said,

Ayahuasca has helped me be more comfortable with gender, which is an interesting one to me because I spent so much time trying to deconstruct my attitudes of beliefs in my upbringing. And yet, I don’t identify strongly as a man; I don’t identify really strongly with primary gender at all. But a part of that has been in reaction to what’s sick around primary gender roles in our culture, and as ayahuasca clears that in me and in my reactions to it, I’m getting more comfortable … So I guess I’m feeling more comfortable as a gay man … I’m a lot more comfortable circling “male” than I used to be.

A gay Santo Daime participant described an experience of angels healing his own homophobic perceptions. He described a session in church in which he had received what he took as an affirmation from God that it was acceptable for him to be gay. After this:

I had this vision of these angels who came up behind me and they just held me … And they were gay angels, and I just fell back into their arms, and they totally supported me. And they took me to this place in the astral, and they just ministered me, and they healed that part of me that has been damaged by society’s homophobia, and by my own homophobia. And I just felt totally safe, and totally nurtured.

He also received with this a warning that while being gay was acceptable, some of the common behaviors of gay men, including impersonal sex, were not.

Two gay men credited ayahuasca experiences with giving them inspiration to come out about their sexual orientation to others they feared disapproved. As one said:

[Since drinking ayahuasca] I started sharing with some close friends about my sexual orientation. And that was the power, that I could have this experience that I could go deep into the plant, and she could open my heart and my fears and allow me to come to a sort of resolution; a look at myself in a such a way that I then went out into the world and made real hard changes in my life.

The other male participant who credited his ayahuasca experiences with helping him to come out about his sexual orientation described a “richer, more joyous life” as the effect of his ayahuasca use. Another gay man told of a vision of having sex with Mestre Irineu, the founder of the Santo Daime church, in which his sexual orientation was affirmed. Two participants described the effect of ayahuasca of removing layers of obstacles to clear perception and acceptance of sexual orientation.

For some participants, ayahuasca had the effect of lessening sexual desire. One woman reported that she had lost the desire for sex and was reserving her energy for ayahuasca. Another participant found that he was able to get control of his sexual impulses and pornography addiction by participating in dietas, a shamanic ayahuasca practice in which alcohol, drugs, sex, sugar, salt, pork, and some other substances are forbidden in order to allow better communication with the plant spirits. One man said that ayahuasca had increased his safer-sex practices, as it had increased his healthful practices in many other ways. One gay man said that as a result of ayahuasca experiences, he sees sexual focus as “something of a joke,” and that his identity as a sexual person had ended; he had transcended the need for sexuality in his life.

Other participants, however, found a deeper experience of sexuality, sexual awakening, and opening. A lesbian participant who had been sexually abused as a child experienced healing of her sexuality through ayahuasca sessions in Santo Daime. She said, “Sexuality and spirituality are so unified in a way that they never used to be before; so much deeper and both cosmic and full body and mind-blowingly sublime.”

A gay man said he felt healed of his sexual addiction and now had sex as an expression of love, rather than for the sake of sex itself. Another gay man said his sexuality was “less genital, more heart.” A male shamanic practitioner described a vision that helped him affirm his sexuality: “Through that simple vision – it was the first time that I really got how important the visions are – in this case it was to do with my sexual energy that was affirming me that it’s so healthy, it’s so intrinsic, it’s so much a part of me. And to not be expressed, not to be embraced, is letting myself live in the world with one part of me just sort of damped down, and unexpressed, and not who I am.”

The element of the group is an important part of the setting. Feelings of inclusion and exclusion are fundamental to spiritual communities, and can influence and help determine the experiences of practitioners. Apart from the intense effects of the drink and its tendency to provoke internal reflections on themes of identity, there are, for gay and lesbian people, also issues relating to how their identity as homosexuals will be perceived by the ayahuasca-using group and its leaders. The values of the group may or may not reflect those of the gay or lesbian drinker or the groups they associate with outside of the rituals.

Most participants did not have a large circle of other ayahuasca-drinking gay or lesbian people with whom to associate but felt supported by the groups they drank ayahuasca with; with the exception of members of their tradition who came from South America, whom they felt were homophobic, though, this was not always the case. One man said he “played straight” with the Peruvian shaman who ran ceremonies he attended. Some members of Santo Daime said that on trips to Brazil, and to Mapiá, the Amazonian home of the church, they did not reveal their sexual orientation and commented on the homophobia in the church in Brazil, contrasting it with the acceptance they felt in the American and European churches. Gender roles are clearly defined in Mapiá, with women, for example, until recently, being required to wear skirts at all times. One woman said, “Mapiá is a horrible place to be gay.” She also felt pressure from a female American church leader to be more feminine than was comfortable for her. All other Santo Daime participants said they felt supported by the local American churches they attended.

Participants in shamanic traditions had less to say about overt homophobia, and none reported feeling rejected by their local group or groups in South America they visited. Some commented on the feeling of closeness with their community of ayahuasca drinkers because they were sharing such intense healing experiences. One 28-year-old gay man said, “I feel comforted and supported for who I am, and overwhelming love and support of other people around me.”

The themes that arose in the area of beliefs about homosexuality showed one of the largest differences between the Santo Daime practitioners and those who drank in shamanic circles. Participants who drank ayahuasca in shamanic circles often were not aware of the beliefs of the shaman regarding homosexuality. Some participants said they did not know or were not concerned with the beliefs of the shaman or group that they practiced with. The participants often met only for the ceremonies, some traveling great distances to attend, following more of a “weekend workshop” model, with several seeing co-participants only during ceremonies. A gay man who drank with an American shaman expressed disbelief that any person who drank ayahuasca could have anti-gay feelings, and he said that he thought ayahuasca would cure people of “this negativity.” He said he would have problems continuing his practice if he felt the shaman was not supportive of him as a gay man. One man who drank with a South American shaman said that he felt the shaman was respectful towards his sexual orientation, asked questions to better understand him, and used inclusive language during ceremony. Another male participant in shamanic circles acknowledged the homophobia in Peru, but described his own experience within his shamanic ayahuasca practice in making peace with the persecution he felt in the past as a gay man within the Christian tradition. He was the only participant who felt it had been a challenge to find peace with the shamanic model as a gay man and that this model was “not necessarily supportive” of alternative sexual expression. This man had also remarked that he disguised his sexual orientation around the shaman.

Participants who drank ayahuasca in Santo Daime were critical of the Christian tradition of rejecting or criticizing gay people. Many looked for personal meaning in Christianity beyond dogma and dismissed ideas that did not match their personal beliefs. Some attributed the homophobia of the Santo Daime church to its Brazilian origins, and said that, in the United States and Europe, they felt accepted and affirmed. One gay Daimista said that, in regard to homosexuality, he didn’t think the church wanted people to go against their nature. Yet, he felt the church leaders ignored homosexuality and noted that it was not celebrated in the church. One man, who married his male partner in an American Santo Daime church and feels supported there, said that he ignores the parts of Christianity which he viewed as perversions of Christ’s message, and attributed these ideas to political “power tripping.” Another man said he regarded Christianity as a metaphor, and though he was a member of Santo Daime, he did not consider himself to be a Christian. He said he ignored what he considered to be the outdated ideas of Christianity in regard to sexuality and homosexuality. One gay member of Santo Daime concluded that Jesus would have been supportive of gay people. A few participants said they wished that the church were more openly supportive of gay people.

This study found that participants reported experiences that changed their lives in positive ways in environments that, even when culturally disapproving of homosexuality, they felt supported them. In this research, all of the ayahuasca drinkers in all modalities (shamanic, Santo Daime, and Afro-Brazilian) felt their sexual orientation was affirmed by their participation in ayahuasca rituals. Participants felt a reinforcement of positive perspectives in their lives, and reported feeling inspired by ayahuasca rituals. The sexual aspect of participants’ lives was enhanced by an increased desire for interpersonal connection and a lessening of feelings of guilt and internalized homophobia, but in some others, the sexual aspect of their lives lost its prominence and was replaced by a spiritual emphasis. Participants in Santo Daime interpreted dogma in ways that enhanced self-acceptance and disregarded doctrine that was judgmental.

The results of this study point to the potential for ayahuasca to enhance gay and lesbian individuals’ self-acceptance and identity, to deepen their relationships, and to help them to re-define themselves in a positive way. Ayahuasca rituals inspired them to live healthier lives, including, for some, increasing safer-sex practices. Insights into healthier sexual behaviors were paired with an appreciation for more honest, authentic relationships. The interviews revealed participants who were profoundly affected by their ayahuasca drinking, who spoke about it in reverential terms, and who were eager to describe the transformations they experienced through their practices. Investigation into the effect on identity brought to light the powerful effect of ayahuasca-induced spiritual experiences on self-acceptance, including an acceptance of one’s sexual orientation. Regardless of the ritual context it was drunk in, ayahuasca seemed to grant the participants a new perspective from which to reflect in a positive way on their identity. Using ideas from Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Integral theory, indigenous belief systems, and other spiritual, cultural, and religious paradigms, participants described their experiences of transformation either in the language and jargon of their ritual tradition, in psychological terms, or in wholly original constructs devised to express novel insights.

In contrast to past studies mentioned previously, in which gay people were treated with psychedelics to help “cure” them of their sexual orientation, participants in this study drank ayahuasca for different reasons and reported acceptance and affirmation of their orientation through participation in ayahuasca rituals. Though no participants in this study were attempting to change their orientation through the use of ayahuasca, several reported struggling with the acceptance of their orientation, and stated that ayahuasca helped them with this.

The self-reports of these ayahuasca users can be contrasted with the reports of researchers with interests in orientation change. The reports gathered for this study depict experiences that affirmed the essential worth of the users’ identity, and this extended to their sexual orientation. Even in settings in Brazil and Peru in which participants perceived homophobia, outcomes of the rituals were affirming of these participants’ same-sex orientation. Safer sex practices, deeper relationships based on trust, and a rejection of superficiality were all cited as outcomes of ayahuasca use.

The sample is small and voluntary and therefore difficult to generalize from. Also, it is important to note the influence of the selection process and the bias that may be inherent in the sample. Participants were generally ayahuasca enthusiasts who sometimes had high levels of devotion and commitment to their practices. They read newsletters and websites about ayahuasca, and so it is likely that they had strong interest probably linked to positive experiences with the tea. They might be characterized as “spiritual seekers,” who may already have a bias to make religious or spiritual sense of their experiences. In addition, the intensity of the ayahuasca experience can create the desire to encourage others to partake in the magic of the ayahuasca ritual and to literally and figuratively “sing the praises” of ayahuasca. Glowing reports of the effects and a minimizing of negative aspects of the experience might be a factor in the responses obtained. However, as noted in other research, negative reports about ayahuasca experiences are rare. Even episodes that were physically or emotionally hard are considered, on reflection, to have been valuable (Harris & Gurel, 2012; Lewis, 2008). This is not to say that there are no negative reports by individuals, but rather that surveys of regular users, or those who frequent ayahuasca sites on the Internet, do not capture this group.

As was noted above, the bias resulting from requesting self-identified lesbians and gay men to respond to this study is predisposed to a positive outlook on same-sex orientation from participants. This may point toward the tendency of ayahuasca to potentially reinforce ideas already present and to reveal different “truths” or to experientially deepen previous convictions, depending on the established beliefs of ritual participants. Because it is a psychoactive substance, often taken in illegal contexts, ayahuasca can be presumed to be of interest initially to those in North America who are less conventional, have past experiences with psychedelics, and who are more likely to have unorthodox or liberal views. In South America, on the contrary, Santo Daime, in particular, originated among non-indigenous residents of the Amazon who were more likely to have traditional, conservative views on social issues and be influenced by the folk-Catholicism and evangelical Christianity of the areas they live in (Silva Sa, 2010).

União do Vegetal officially declined to participate in this research, so no conclusions can be drawn about how their religious views might impact any gay or lesbian members. In addition, no “ex-gays” from any ayahuasca tradition were interviewed; this would prove a fascinating area of research to contrast with the results obtained in this study.

Finally, it should be noted that many gay and lesbian participants in the ayahuasca churches in Brazil do not experience this same affirmation of their sexual orientation, to the point that some have been inspired by their experiences in Santo Daime and the União do Vegetal churches to become asexual or to marry and adopt heterosexual lifestyles (personal communication, Edward MacRae, 2009; personal communication, Beatriz C. Labate, 2010). While some of the anecdotal reports from Brazil seem to support the idea of using psychedelics to “correct” homosexuality, the strong influence of cultural “set and setting” on these experiences is a notable consideration. In countries where gay people have little protective community of their own, religious communities that revolve around ayahuasca drinking may inspire gay people to try to fit in with heterosexual family ideals that are promoted as antidotes to modern problems in the “world of illusion.” The social environment of Santo Daime communities emphasizes family and traditional, patriarchal values, which have little room for flexibility in sexual orientation or non-conformity to gender stereotypes. This can be expected to change as society generally becomes more inclusive and the social movement toward accepting homosexuality and gender fluidity spreads throughout the Western world.

The context in which ayahuasca was drunk (church vs. shamanic ceremony) did not seem to create substantial differences in the themes related to the social and sexual identities of the study participants. The participants largely relied on their own interpretations of their ayahuasca experiences. Those in Santo Daime dismissed or re-interpreted elements of Christian dogma that were unsupportive of gay or lesbian sexual orientation. Participants in all traditions who were interviewed focused on self-knowledge and healing, and described general enhancements to their lives as a result of participation in ayahuasca rituals that ranged from ontological revelations to changes in addictive behaviors, safer sex behaviors, enhanced personal relationships, and improved physical health. Overall, the interviews revealed grateful ayahuasca drinkers who remarked mainly on the benefits they had received from ritual participation and the acceptance they felt within their chosen group. For all the participants, ayahuasca ceremonies provided an environment that they felt supported their gay or lesbian identities and led to increased acceptance of and compassion for their identity as gay people.

The growing tide of people drinking ayahuasca worldwide continues to rise, bringing with it people with varied backgrounds, orientations, and religious views. Many people who return for a second and future rituals with the brew have found renewed hope, affirmation in their lives of their personal value, and increases in the qualities of humility, generosity, honesty, and compassion; these qualities are often tied to spiritual progress. People who have been rejected and told they are inherently sinful find it challenging to maintain a positive identity in the face of societal judgment. The research presented here shows a consistent response after ayahuasca use of affirmation of identity, with homosexuality being but one precious part, and a marked increase in positive self-regard in the participants.

Possibilities for future research might include a comparison of the experiences of Brazilian and Peruvian ayahuasca drinkers, including members of the UDV, who opted for heterosexual lifestyles in conformance to church or cultural norms in their ayahuasca-drinking communities, to see how these accommodations are made. Research comparing gay and lesbian ayahuasca drinkers in South America would likely illuminate how cultural differences impact interpretations of experience. Finally, this study points to the question: could ayahuasca be taken in therapeutic settings by sexual minorities experiencing problems with identity issues? Many possibilities for further research exist. Both within and far from the jungle, ayahuasca has deeply affected the lives of those who drink it, awakening deeper appreciation for their identities and opening new paths to personal healing and life satisfaction.

Alpert, R. (1969). LSD and sexuality. The Psychedelic Review, 10, 21–24.

American Psychological Association (APA) (2008). Answers to your questions: For a better understanding of sexual orientation and homosexuality. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from Febuary 20, 2013 www.apa.org/topics/sorientation.pdf.

Amoroso, T., & Workman, M. (2016). Treating posttraumatic stress disorder with MDMA-assisted psychotherapy: A preliminary meta-analysis and comparison to prolonged exposure therapy. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(7), 595–600.

Anderson, B. T. (2012). Ayahuasca as antidepressant? Psychedelics and styles of reasoning in psychiatry. Anthropology of Consciousness, 23(1), 44–59.

Apatow, J., Marino, K., Rudd, P. (Producers) & Wain, D. (Directors) (2012). Wanderlust.

Barbosa, P. C. R., Cazorla, I. M., Giglio, J. S., & Strassman, R. (2009). A six-month prospective evaluation of personality traits, psychiatric symptoms and quality of life in ayahuasca-naive subjects. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 41(3), 205–212.

Barbosa, P. C. R., Joel Sales Giglio, J. S., & Dalgalarrondo, P. (2005). Altered states of consciousness and short-term psychological after-effects induced by the first time ritual use of ayahuasca in an urban context in Brazil. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 37(2), 193–201.

Berkowitz, J. (2008). Word to the mother: How I gave it up on my 30th birthday (I tried it). Curve, 77(1). doi: A179885525

Bouso, J. C. (2012). Ayahuasca scientific literature overview. Halstern, The Netherlands: ICEERS. Retrieved August 14, 2016 from www.iceers.org/docs/science/ayahuasca/ICEERS2012_Ayahuasca_literature_compilation.pdf

Burroughs, W. R. & Ginsberg, A. (1963). The yage letters. San Francisco, CA: City Lights.

Cavnar, C. (2011). The effects of participation in ayahuasca rituals on gays’ and lesbians’ self perception. (PhD Diss). John F. Kennedy University, Pleasant Hill, CA.

Comstock, G. D. (1996). Unrepentant, self-affirming, practicing: Lesbian/bisexual/gay people within organized religion. New York, NY: Continuum.

Cox, S., & Gallois, C. (1996). Gay and lesbian identity development. Journal of Homosexuality, 30(4), 1–30.

Denny, D. (2006). The last time I dropped acid. Transgender Tapestry, 110(Fall), 63.

Diamond, L. M. (2000). Explaining diversity in the development of same-sex sexuality among young women. Journal of Social Issues, 56(2), 297–313.

Drescher, J., & Zucker, K. J. (2006). Ex-Gay Research: Analyzing the Spitzer Study and its Relation to Science, Religion, Politics, and Culture. Philadelphia, PA: Haworth Press.

Dube, R. (2016, April 30). Is Peru’s psychedelic potion a cure or a curse? Wall Street Journal.

Fábregas, J. M., González, D., Fondevila, S., Cutchet, M., Fernández, X., Barbosa, P. C. R., … Bouso, J. C. (2010). Assessment of addiction severity among ritual users of ayahuasca. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 11(3), 257–261.

Flick, U. (2002). An introduction to qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Fotiou, E. (2010). From medicine men to day trippers: Shamanic tourism in Iquitos, Peru. (PhD Diss.), University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Ginsberg, A. (1966). Exhibit 75. The Narcotic Rehabilitation Act of 1966: Hearings before a special subcommittee of the committee on the judiciary of the United States 89th congress pursuant to S. Res. 199, S. 2113, S. 2114, S. 2152 and LSD and marihuana on college campuses. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Greenham, J. (2015, March 17). Ayahuasca gave me the courage and support to come out as transgender and begin my transition. Reset.me.com. Retrieved August 28, 2016 from http://reset.me/personal-story/ayahuasca-gave-me-the-courage-and-support-to-come-out-as-transgender-and-begin-my-transition/

Grob, C. S., Danforth, A. L., Chopra, G. S., Hagerty, M., McKay, C. R., Halberstadt, A. L., Greer, G. R. (2011). Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(1), 71–78. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.116

Grof, S. (2000). The psychology of the future: Lessons from modern consciousness research. State University of New York Press.

Haas, A. P., Elliason, M., Mays, V. M., Mathy, R. M., Cochran, S. D., D’Augelli, A. R., … Silverman, M. M. (2011). Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58, 10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038

Harris, R., & Gurel, L. (2012). A study of ayahuasca use in North America. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 44(3), 209–215.

Hattie, B., & Beagan, B. L. (2013). Reconfiguring spirituality and sexual/gender identity: “It’s a feeling of connection to something bigger, it’s part of a wholeness.” Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 32(3), 244–268. doi: 10.1080/15426432.2013.801733

Holman, C. (2011). Surfing for a shaman: Analyzing an ayahuasca website. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(1), 90–109.

Howland, R. H. (2016). Antidepressant, antipsychotic, and hallucinogen drugs for the treatment of psychiatric disorders: A convergence at the serotonin-2a receptor. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 54(7), 21–24. doi: 10.3928/02793695–20160616–09

Kelly, M. (2008). Research on psychedelics moves into the mainstream. The Lancet, 371(9623), 1491–1492.

Kjellgren, A., Eriksson, A., & Norlander, T. (2009). Experiences of encounters with ayahuasca: “The vine of the soul.” The Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 41(4), 309–315.

Labate, B. C., & Cavnar, C. (2011). The expansion of the field of research on ayahuasca: Some reflections about the ayahuasca track at the 2010 MAPS “Psychedelic Science in the 21st Century” conference. Journal of International Drug Policy, 22(2), 174–178.

Labate, B.C., & Cavnar, C. (Eds.). (2013). The therapeutic use of ayahuasca. Heidelberg: Springer.

Labate, B.C. & Cavnar, C. (Eds.). (2014). Ayahuasca shamanism in the Amazon and beyond. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Labate, B. C. & Jungaberle, H. (Eds.). (2011). The internationalization of ayahuasca. Zurich: Lit Verlag.

Labate, B. C., Santana, I., & Santos, R. G. (2008). Ayahuasca religions: A comprehensive bibliography and critical essays. Santa Cruz, CA: MAPS.

Labate, B. C., Santos, R. G., Anderson, B. T., Mercante, M., & Barbosa, P. C. R. (2010). The treatment and handling of substance dependency with ayahuasca: Reflections on current and future research. In B. C. Labate & E. MacRae (Eds.), Ayahuasca, ritual, and religion in Brazil (pp. 205–227). London: Equinox.

Leuner, H. (1993). Hallucinogens as an aid in psychotherapy: Basic principles and results. In A. Pletscher & D. Ladewig (Eds.), Fifty years of LSD: Current status and perspectives on hallucinogens. New York City, NY: Parthenon.

Lewis, S. E. (2008). Ayahuasca and spiritual crisis: Liminality as space for personal growth. Anthropology of Consciousness, 19(2), 109–133.

Mabit, M. (1996). Takiwasi: Ayahuasca and shamanism in addiction therapy. MAPS, 6(3). Retrieved August 16, 2016 from www.maps.org/news-letters/v06n3/06324aya.html

Martin, A. J. (1962). The treatment of twelve male homosexuals with LSD. [Abstract] Acta Psychotherapeutica, 10, 394–402.

Masters, R., & Houston, J. (1966/2000). The varieties of psychedelic experience. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.

Monteiro de Souza, R., Belmonte dos Santos, L. P., Rodrigues do Carvalho, C. C., & Campos Soares, E. L. (2008). Religious position of the representatives of this center (Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal) on important contemporary topics. Downloaded June 28, 2013 from ayahuasca.com, http://forums.ayahuasca.com/viewtopic.php?f=46&t=24013

Nielson, J. L., & Megler, J. D. (2013). Ayahuasca as a candidate therapy for PTSD. In B. C. Labate & C. Cavnar (Eds.), The therapeutic use of ayahuasca (pp. 41–58). Heidelberg: Springer.

Orion, D. (2015, May 21). Benefits of microdosing with LSD and psilocybin mushrooms. Resetme.com. Retrieved August 7, 2016 from http://reset.me/story/benefits-of-microdosing-with-lsd-and-psilocybin-mushrooms/

Palladino, L. (2009). Vine of soul: A phenomenological study of ayahuasca and its effect on depression (PhD Diss.), Pacifica Graduate Institute, Carpinteria, CA.

Sandison, R. (2001). A century of psychiatry, psychotherapy and group analysis: A search for integration. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Press.

Santos, R. G. D. (2013a). Safety and side effects of ayahuasca in humans: An overview focusing on developmental toxicology. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45(1), 68–78. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2013.763564

Santos, R. G. D. (2013b). A critical evaluation of reports associating ayahuasca with life-threatening adverse reactions. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45(2), 179–188.

Schmid, J., Jungaberle, H., & Verres, R. (2010). Subjective theories about (self-) treatment with ayahuasca. Anthropology of Consciousness, 21(2), 188–204.

Shanon, B. (2002). The antipodes of the mind: Charting the phenomenology of the ayahuasca experience. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Shanon, B. (2010). The epistemics of ayahuasca visions. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 263–280.

Silva Sa, D. B. G. (2010). Ayahuasca: The consciousness of expansion (C. Frenopoulo, Trans. and M. Meyer, Rev.). In B. C. Labate & E. MacRae (Eds.), Ayahuasca, ritual and religion in Brazil. London: Equinox. (Reprinted from Discursos sediciosos. Crime, direito e sociedade [Seditious speeches: Crime, law and society] by Instituto Carioca de Crimiologia, 1996, 145–174. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Carioca de Crimiologia.

Snelders, S., & Kaplan, C. (2002). LSD therapy in Dutch psychiatry: Changing socio-political settings and medical sets. Medical History, 46(2), 221–240.

Sprinkle, A. (2002). How psychedelics informed my sex life and sex work. MAPS Bulletin, 12(1), 9–13.

Stafford, P., & Golightly, B. (1967). LSD: The problem-solving psychedelic. New York City, NY: Avon. Retrieved from www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/lsd/staf4.htm

Sulla, J. (2005). The system of healing used in the Santo Daime community Ceu do Mapiá (Master’s thesis). Saybrook Institute, San Francisco, CA.

Suppe, F. (1984). Classifying sexual disorders. Journal of Homosexuality, 9(4), 9–28.

Tolbert, R. (2003). Gender and psychedelic medicine: Rebirthing the archetypes. Revision, 25(3), 4–11.

Trichter, S. (2009). Changes in spirituality among ayahuasca ceremony novice participants. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 41(2), 121–134.

University of Virginia. (2015, July 26). Implicit bias against lesbians, gays decreasing across demographic groups, study shows. ScienceDaily. Retrieved August 6, 2016 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/07/150723083718.htm

Williams, L. (1999). Human psychedelic research: A historical and sociological analysis. Undergraduate thesis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Young, B. (2003). Journeying. White Crane Review, 56(Spring), 14–15.