MAKING A START

While there is obviously no substitute for watching a teacher perform the brush strokes and mix the ink, and then attempting the techniques yourself, this book is meant to provide the next best thing to traditional lessons in Chinese brush painting. You should regard the book as providing a course and try to master each stage before going on to the next.

The Chinese method of learning anything, be it painting or kung fu, can be broken down into three steps: watch; do; understand. You can learn by imitation and repetition until finally the chi flows through you and you understand. In other words, you should not worry about why you are doing something – its purpose will become clear in time. In this book I have tried to give instructions to cover the watching and imitating stages; the rest is up to you.

In Chinese brush painting there is a logical sequence of learning, evolved over centuries, which will enable you to build up your repertoire of brush strokes just as a trainee instrumentalist builds up his repertoire of notes and scales. The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (1679-1701) has advice for the would-be painter on the need for being methodical:

He who is learning to paint ... should begin to study the basic brush stroke technique of one school. He should be sure that he is learning what he set out to learn, and that heart and hand are in accord. After this, he may try miscellaneous brush strokes of other schools and use them as he pleases. He will then be at the stage when he himself may set up the matrix in the furnace and, as it were, cast in all kinds of brush strokes of whatever schools and in whatever proportion he chooses. He himself may become a master and the founder of a school. At this later stage, it is good to forget the classifications and to create one’s own combinations of brush strokes. At the beginning, however, the various brush strokes should not be mixed.4

Even Fang Zhaoling, who is one of the most innovative Chinese painters working today, exhibiting in the USA, the UK, Hong Kong and China, recognizes that it was vital for her to have a thorough grounding in basic brushwork. She spent ten years studying under Zhao Shaoang of the Lingnam school before she felt the need to break away and the confidence to express herself by creating her own style.

The best way to learn is to practise each stage thoroughly. You must be patient, however, and prepared to work hard. Only by constant practice will you learn to paint with confidence and ease.

Do not let yourself become discouraged during these early stages. At first you may feel that you will never progress beyond the basics, but it is vital to be most thorough at the beginning or you will never achieve the facility and effortlessness that are the hallmarks of a successful brush painting. Eventually you will be rewarded by finding that later lessons take less time to learn. In any case, the learning process is a continuous one: my own teacher claimed he was still learning after fifty years.

One of my students related a no-doubt apocryphal story she had heard about a man who went to a famous Chinese painter to commission a picture. He was told to come back a year later and this he duly did. On seeing his customer, the painter got out paper, brush, ink and ink stone; he ground the ink and in a few strokes completed a painting which was exactly what was required. The customer was mystified and enquired about the need for a year’s delay. Without a word, the artist got up from his seat at the table and opened a cupboard in a corner of the room. It was full of practice versions of the painting on the table.

The correct way to hold the brush

Before you begin to paint, there are several general points you should always remember. First of all, try to be in a calm and contemplative frame of mind. Take time over preparing your materials; make sure that your physical environment is soothing; shut yourself away in a quiet corner (the kitchen table with children underfoot clamouring for tea is not to be recommended). Enjoy the process of getting ready to paint before you actually start the painting itself.

You should always strive for sureness and boldness in your brush strokes. Even when the subject of your painting is small and detailed, the individual brush strokes should be deft and certain. This may result in somewhat unkempt results to begin with, but you should remember that the Chinese admire paintings that are chuo, or awkward, and are scathing about those that are dextrous but lack feeling. In time you will find that you gain control over the brush and can make it do what you want without losing any spontaneity.

When you are learning by copying it is important not to be too slavish about it. A very common mistake is to continue to look at what you are copying while actually painting. This results in a hesitant line. You should look at the subject before putting brush to paper and then reproduce an impression of it from memory. To help you to achieve spontaneity and feeling in your painting you should always use as large a brush as it is practical to use for any given subject. This encourages you to use fewer strokes.

Holding the brush correctly

A Chinese brush is held quite differently from a Western one. It should always be held as upright as possible, between the thumb and the middle finger with the other three fingers providing guidance rather than support, the index finger in front of the brush and the ring and little fingers keeping it upright from behind. The brush should be loosely held, not tightly gripped. For small details you may hold it fairly close to the bristles, but larger, freer strokes are done with the brush held quite high up the haft. The movement of the strokes comes from the shoulder, not from the wrist, so you should ensure that you are sitting or standing in a relaxed but upright position, with plenty of freedom for your shoulder to move.

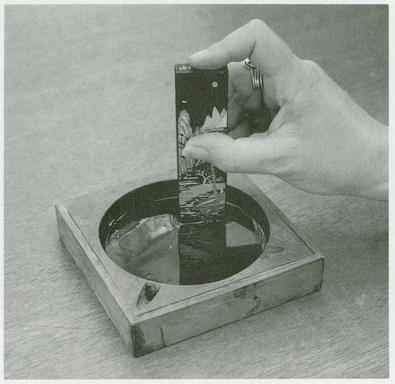

Use a circular motion to grind the ink

Grinding the ink

It is crucial to grind your ink black enough: nothing mars the effect of a picture so much as poor ink values. You should grind your ink stick from the bottom – you can work out which end this is from the calligraphy or picture on the side of the stick - for the ink at the top of the stick, where you hold it, is often less dense. Some experts claim that distilled water should be used for grinding ink but this is not normally done. Put a few drops of water onto the grinding surface of the ink stone and holding the ink stick upright, grind it with circular movements until the motion leaves a dry patch on the stone. This indicates that the water has absorbed as much ink as possible. However, you should always test the ink to make sure that it is a good, rich black. Take care not to leave the ink stick upright on the stone because the moistened glue within it will cause adhesion.

Grey tones are achieved by placing a small amount of black ink on a china palette and diluting it to the desired shade with water. Some subjects require a great deal of ink, others less. It is a common fault of students not to grind enough ink and to try to stretch it too far by overdiluting.

Composition

Be careful about composition. Allow yourself a piece of paper that is larger than you think you will need. This should help you to avoid a tendency some people have to make their subjects too small and therefore rather cramped. However, you must also avoid the opposite temptation, which is to fill the paper completely. Remember that space is an essential element of composition in Chinese painting. Westerners tend to worry about unused space in paintings and seem to have a distressing need to fill it, but you must learn to curb this desire when you are brush painting.

The amount of space devoted to individual subjects in this book is not necessarily indicative of the amount of practice they demand. It is simply that as you progress through the course, I shall assume a certain knowledge has already been acquired, allowing later subjects to be dealt with in less detail.

For most topics I begin by considering what is often called the ‘outline’, or contour, method and then go on to discuss the ‘freestyle’ technique. This distinction is useful for explanatory purposes, but no painting need be done exclusively in one or other method. For example, outlined flowers will often be accompanied by freestyle leaves, or an outlined bird will be perched on a freestyle branch.