YOU HAVE NO CONTROL OVER YOUR PAWN. IT GOES WHERE THE STICKS TELL IT

The road from the border city to Sareeb began as a desert, and ended in a lush forest. It was a gradual change, brought on by the many rivers that forked off from the Hiperu, creating the large delta. Every day there was more life around them, more magnificent colours, more birdcalls, more encounters with local merchants who travelled along the road for trade. The closer they got to Sareeb, the more people they saw, and not just merchants. They saw entire families, seemingly carrying everything they owned, walking with empty eyes.

As a general rule they avoided speaking to anyone. Kareth and Tersh would wait along the side of the road in the trees. The Whisperers were not welcome in this part of the world. Where most places they were respected for their connection to the gods, here they were feared for it. It wasn’t difficult to convince Kareth to hide. Since crossing the border he had become quieter. He always had a serious look on his face, as though he were lost in thought.

When she had been Kareth’s age, Tersh’s tribe had travelled to the Sea Mahat. During the calendar ceremony a plague was predicted along the fishing villages her people traded with, so their chief decided to take them across the border where he believed they would be safe. They had stayed along the shore through several constellations. Tersh learned the language and customs of these people. Tersh never forgot the beauty of this land and never stopped yearning to return. She would probably never stop being disappointed she didn’t get to stay in Mahat as its messenger, but she was thankful that at least the gods sent her on a path that would take her through Mahat.

At night, they camped at the side of the road amongst the trees. Kareth had an easy time falling to sleep. Tersh would spend a long time looking up at the stars, remembering all the nights she had done the same, only lying next to Ka’rel’s warm body instead. She could still smell the salt of his skin as she drifted off. One morning, Kareth woke with a start just as Tersh was making a fire.

“You look as though you still wear a cloak of dreams,” Tersh had remarked, trying to make him smile, but the boy only scowled at the ground.

Tersh cooked some fish over a small fire, the entire time Kareth saying not a word. It wasn’t until after they’d eaten, when Tersh was pouring dirt over the hot embers, that he made a noise.

“Could a man be sent a vision from the gods?”

“A man?” Tersh shrugged. “I think maybe that’s a woman’s providence. Only a woman can be Rhagepe. Only Rhagepe can hear the gods.”

“But I was chosen to speak for the gods as well, and I’m a man.”

Barely a man. “You were chosen to be a messenger, not a Rhagepe,” the questions were beginning to make her feel uncomfortable.

“I dreamt of two great white birds, sent from the gods, to carry us on our journey,” his voice seemed distant.

“I dream every night. It does not mean those dreams were sent by the gods.”

They began to walk, and it was a long time before Kareth spoke again.

“Do you think… when I performed that ceremony…?”

Tersh couldn’t help but laugh, but quickly stopped when she saw the hurt look in Kareth’s face. “It wasn’t a real ceremony.”

“Yes, I know I made it up… but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t real. I felt something,” Kareth pointed his silver eyes up at the sky. “I feel like something inside me… opened. Whatever I did back at the border… my mother would say it was like picking up a random rock, only to break it open and find it’s full of quartz.”

Tersh looked at Kareth. She wondered how much of what he was saying was nothing but a boy’s imagination and how much of it could actually be true. What did she know of the Rhagepe? The boy had silver eyes. He had been chosen to speak for a god. How could she say he did or did not receive a vision from the gods? If the gods wanted them to be their voice, it was possible they might also send them visions in order to guide them.

“Two birds, you say?”

Kareth turned towards her, his face brightening. “Yes. I think the gods are trying to tell us of how to proceed next.”

“None of the birds I’ve seen in these parts could carry us anywhere. Besides, we’re nearly at Sareeb. Your journey is nearly ended.”

Kareth sighed. “Maybe… maybe the gods are saying that this journey is only beginning.”

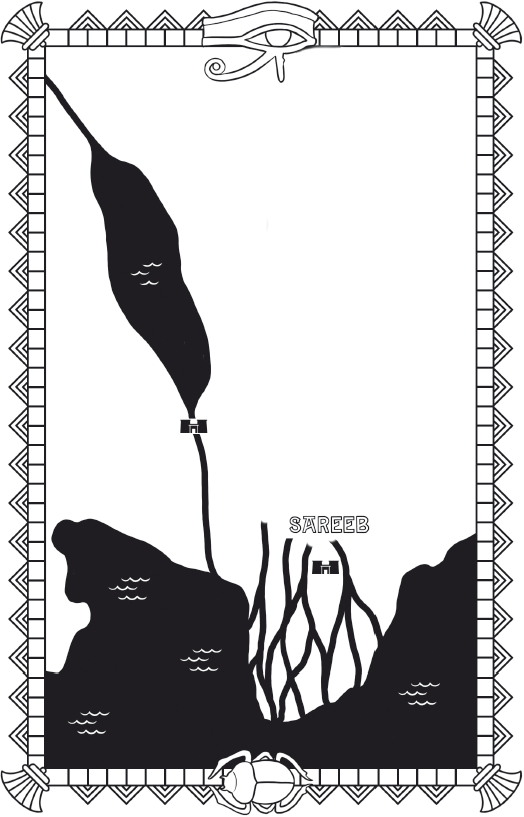

After the sun had reached its zenith and begun to descend once more, they saw Sareeb for the first time. The ground slanted down, and they could see the entirety of the city before them. They both had to stop walking and stare in stunned silence. This was perhaps ten times the size of the border city, with dozens of massive pillared-temples. It was split in two, a large river going down its centre, ending in a lake on the south side of the city walls. More shocking still was when they noticed that the lake had swallowed up the southern half of the city. They could see the tops of trees and buildings, people using boats to move through narrow alleys.

A flood.

Tersh felt weak.

“It’s begun,” Kareth whispered.

Tersh could only shake her head. “We don’t know that.”

“The city is flooded!” Kareth turned to her. “Their chief is dead and the flood has already come! We’re too late!”

“We are not too late,” Tersh took the boy’s shoulders in his hands, her stern, dark eyes staring him down, her voice calm and level. “The city still lives. The gods have given them a warning, but the flood is not complete. The Rhagepe told us the floods would touch every constellation in the full cycle. The gods would not have sent us if there wasn’t any time to stop this.”

Slowly Kareth nodded his head.

As they walked the rest of the way they both finally understood the lines of people they had seen heading for the border. They were escaping this, carrying what little they owned, praying that the flood would not follow them west. Tersh could only hope that was true.

Once they reached the city they could see the damage was much worse than they had though. The water had cascaded over the city walls with such force that many of the tall statues on the south side of the city had been toppled over or broken in two. They entered from the west side, the gates open and no guards anywhere to be seen. There were people milling through wrecked houses, lifting up stones as they waded ankle-deep in water. Everyone had the same tired expression on their faces. In a small square along the river bodies had been piled up. There were hundreds of them. Most of their eyes were still open, bulging out of their heads as they had gasped for breath in their final moments.

“What happened here?” Tersh asked a man who was tending to one of the bodies. The body lay on a wooden table next to the pile and the man was cleaning it while his younger assistant was stripping him of his clothes and jewellery. They both wore dirty tunics and stubble had begun to grow on their heads. She had never seen the people of Mahat looking so dishevelled.

The man shook his head, barely noticing who was speaking to him. He was indifferent, but to Tersh’s surprise he did not give her the disdain she was used to experiencing with these people.

“A wave came from the south, two – no,” he wiped the sweat from his face, “three days ago? Many waves, torrents of water. I honestly couldn’t say how many. I’ve barely slept since. I’ve never… Half the city was drowned. The water went to the very steps of the White Palace.”

The White Palace was in the centre of the city, sitting on the eastern riverbank. It was the highest building there, a massive three or four storey rectangular structure. The walls angled inward ever so slightly so that the top was narrower than the base. It was built of stone so white it shone like a beacon. At the four corners were white obelisks tipped with gold. The southeastern one had fallen. It lay shattered, discarded, as so many of the city’s citizens had been. Tersh noticed the water no longer reached the palace. It had receded. The thought made her smile. It truly was only a warning. The waters were leaving. They still had time – before the flood came again.

“What does he say?” Kareth asked impatiently.

“The waters are receding,” Tersh smiled at him. “Now we must go see this new chief of theirs.”

They needed to find a way to cross the water. When they reached the river they realized with some shock that there were no bridges. It was not because they had been washed away, but rather no bridge had ever been built there. The river was much too wide, and the bank muddy. The water itself was filled with large boats travelling through.

“They must use ferries.” Tersh looked up and down the river, but saw none of the small boats normally used for ferrying travellers. In all likelihood they were in the southern part of the city, perhaps looking for survivors, or going through drowned houses to loot whatever had been left behind.

She glanced at Kareth for a reaction. He wasn’t paying attention to her. His eyes were focused on the White Palace across the river. Tersh turned to see what had captured his attention. A stone path led from the palace to the water. It was lined with dozens of statues of men holding spears. Each had one foot forward as though they had been turned to stone mid-march. At the end of the path was a wooden pier along which were four grand golden barges painted with the colour of marsh flowers. They were a multitude of sparks and hues, a thousand different birds giving flight, with the bow and stern pointed up and carved to look like bushels of wheat.

Tersh smiled at Kareth, whose mouth hung open as he stared at the glittering boats. They had golden cabins set near the back. The cabins were so large they looked like they could have housed an entire family. At each cabin’s four corners stood a statue of a man, but each statue had the head of a different animal, the head of a heron, the head of a leopard, the head of a crocodile, and the head of a jackal. At the top of the ornately carved cabin was an eye facing the bow.

“They’re not really made of gold,” a woman spoke to them.

Tersh looked to her right and saw a bald, broad-shouldered woman, with skin like a fire knife looking at her with a smile. She wore a bright red vest and large baggy grey pants. On her chest and hands, she wore many silver and gold amulets. Tersh couldn’t tell if she was a merchant or a pirate. Both looked much the same to her.

“I’m… sorry?” Tersh asked, noticing that there were actually quite a number of people lined up along the river, staring at the golden barges.

“The ships are made of wood, like any ship. They took sheets of thin gold, and used paint to stick it to the sides. Otherwise, she could not float.” The woman’s accent was not from these parts though her use of the tongue of Mahat was nearly perfect.

“How do you know?”

“Who is she?” Kareth asked, but Tersh ignored him.

“I build ships. It is my trade. My name is Tiyharqu.”

“Tee.. yuha…?”

“You may call me Harqu, if it is easier, Go-man.”

It had been a long time since she had been called Go-man. In their own tongue they called themselves Gogepe, Whisperers of the Gods, but many people either did not know the meaning, or simply enjoyed the sound of saying Go-man. Tersh didn’t mind. It was certainly better than the other name people called them. Rattlecloaks.

“I am called Tersh Hal’Reekrah of the tribe Go’angrin. He is called Kareth Al’Resh, of the tribe Gorikin.”

“And where are your tribes?”

“In the Sea of Sand. We have come alone… with a warning, from the gods.”

“A warning for whom?” Tiyharqu asked, her smile never fading.

“We must speak to the chief, the leader of this place.”

“I’m sorry, you should have come earlier,” Tiyharqu pointed back towards the palace. “See, the King is leaving Sareeb.”

Tersh looked back and saw a retinue of people walking down the path from the palace to the golden barges. There were a dozen or so guards. These guards dressed just as the ones at the border. The familiar pleated white linen skirts, each belted at the waste, bright amethyst being revealed in the folds, and on their heads they wore nemes of the same royal colour. Each one held a black spear tipped in bronze, and short-shorts hung from their belts. They looked like living versions of the statues they walked beside.

Behind them walked young women wearing sheer white tunics, revealing their breasts and dark nipples beneath. They wore wigs of black braided hair. They held up half a dozen awnings stitched with golden threads, making them glitter in the sun. Underneath the awnings they had to squint to see the royal family shaded in darkness. They walked with their backs straight and chins high, wearing ornate wigs and tunics that went down to the ground, with sky and golden threads. A man, Tersh assumed was the Paref, was first. He wore a strange cap on his head, it was tall and stiff and a dark river colour. Behind him walked a shimmering woman and further behind still went several children.

“They go to seek the Paref.”

“The Paref ? That isn’t him?” Tersh pointed to the man walking under the first awning.

“No, that is Utarna, the King of the Sea Mahat. The Paref lives up north, in Nepata. My ship sails for there as well.”

“Tersh, what is happening?” Kareth whined behind her.

“Your ship? You mean one you built?”

“Yes, the Afeth. She is not as beautiful as those barges, but to me she’s worth a thousand such ships.”

“I–” Tersh stopped herself from speaking. She was about to tell the woman how they had to travel to Nepata, to speak with the Paref and deliver their warning, but what good would that do? The Whisperers were unwelcome in these parts. She certainly wouldn’t offer to take them – at least, not unless Tersh thought of a way to convince her.

“Have you captained your ship long?” Tersh finally asked.

Tiyharqu laughed pleasantly. “I have never captained her, though I have watched over the Afeth while her captain was on shore.”

“You are not the captain?”

“No, I am the builder. Perhaps, I am the mother of the Afeth, but Samaki is the father. He is captain.” Again she laughed, this time her voice booming across the river as the gold-tipped oars of the barge were placed into the water, and they began to pull away from the land.

Tersh pointed to the closest ship anchored in the river to them. It was a small ship, a crew of five or so manned her, and its sail was dirty and tattered. “Is that your ship? It is not grand like the King’s, but it does look sturdy.”

“That?” Tiyharqu pointed at the ship, a wounded look coming over her face. “That ship is nothing. The Afeth is, next to a golden barge, the grandest ship on the Hiperu!”

“Could I see her?”

She looked uneasy, maybe worried about being seen walking with a Whisperer. “Well, she isn’t far, if you want to look. I don’t mind showing you the way.”

“I’m going to go, but I’ll be back soon,” Tersh turned to Kareth, explaining quickly.

“Where will you go?”

“We need a ship if we want to speak with their chiefs, and maybe I’ve found one, but it will be easier if you stay here.”

“They have more than one chief ?” Kareth asked in confusion.

“Yes, I never really understood it myself. Every city has a chief, and there is another greater chief above him. Him they call the Paref, the chief of chiefs. They think he is a god. I thought he would be here, but Harqu tells me the Sea Mahat Chief is travelling north to see the Paref,” Tersh explained quickly, worried Tiyharqu would lose her patience.

“And the Paref is dead?”

“Dead, only for his son to take his place. There will always be a Paref in Mahat. Now stay here,” she handed Kareth her spear, just in case. “If you move, I may never find you again with so many people.”

She turned, taking her skins with her, knowing she would need to use gold or jewels to barter. She didn’t really think it would be hard to find Kareth. Whisperers couldn’t help standing out in a crowd, but she certainly didn’t want to waste any time looking for him if this Captain Samaki decided to take them on board.

Tiyharqu led them north along the riverbed. They weaved through countless people watching the golden ships leave, each person silent and unmoving, a deep sorrow in their eyes as they watched their King abandon them. They didn’t walk far. All the ships were grouped together in this one area along the bank.

“There she is.” Tiyharqu stopped and pointed towards a ship anchored a short distance from the shore. There were no docks or piers here. No large ship could come closer. There were several small ships anchored in the area, but the Afeth was by far the largest. The spine of the ship resembled a red snake, its head rearing up at the front, ready to strike, its tail at the back coiled around a lantern. Unlike the other ships surrounding her that either had no mast or only one, she had two white sails. The oars were pulled up into the rowlocks, crisscrossed across the empty deck. “Maki,” Tiyharqu called out to a man sitting on the shore, “Do not look at those golden ships with such longing, for surely Afeth will become jealous.”

There were two men sitting there on the rubble of a building, whether it had been damaged during the flood or if it had just fallen down due to disrepair was hard to tell. They both sat on stones, and between them on a larger piece of rubble was a small, long wooden box Tersh immediately recognized as a senet box. Although the men were sitting towards each other, both of them were staring at King Utarna’s ships as they rowed away.

The man closest to them, Samaki, turned towards them. He wore auburn wool pants, belted with snakeskin and a gold buckle. There was nothing on his muscular chest save half a dozen amulets of precious metals. His head was shaved, so she guessed he was from Mahat. He was tall, though to Tersh all men in Mahat seemed taller than average. He smiled at Tiyharqu, his face friendly but weathered by a long time on the open sea.

“What’s this you’ve found? Whisperers in Sareeb? A most uncommon sight.”

“I am called–” Tersh began, but Tiyharqu cut her off.

“This Go-man thought some dilapidated dingy was the Afeth, so I had to show her the error of her ways.”

“I am called–”

“I don’t care,” Samaki cut her off this time, turning back to the game of senet.

Tiyharqu beamed at her ship, her face filled with pride. “Well, what do you think?”

“Uh, beautiful. Truly.” She meant it too. She would have assumed it was a ship built for the Paref, if the golden ships weren’t still glistening behind it. However, she wasn’t looking at the ship. She was looking at the captain playing senet.

Tersh took a step towards them. She knew the game well, and had often played it when she had lived in Mahat. For a while she had even owned a senet box, but it had been lost or traded ages ago. The box was both what the game was played on and where the pieces were kept. The box they were playing on was a simple one, made out of aged wood. The top had a grid of thirty squares arranged in rows of three carved into it. Ten pieces, five cones and five spools, were on the grid, spread out in various positions, or next to the box. The last five squares were the only ones with any markings, hieroglyphs she didn’t understand outside of their meaning in the game.

“Are you winning, captain?” Tersh asked, leaning over his shoulder.

Samaki gave her an annoyed look, “I never win against Hamota.”

Hamota, a bald man with black stubble on his chin smiled wide. “I am simply a lucky man.”

“How do you play?” Tersh asked.

Samaki narrowed his eyes. “You speak my tongue well enough. In all your time in Mahat, you never encountered senet?”

Tersh smiled innocently. “Oh, of course I have. I meant what rules, no one I’ve met can agree on them. How do you play?”

Samaki regarded her a moment, and then maybe because he was annoyed with losing, or maybe because he was curious about the Whisperer, he motioned towards Hamota. “Sit, I’ll show you.”

“We haven’t finished yet,” Hamota protested.

“We’re finished. You won – again.”

“It’s always a pleasure, captain,” Hamota rose from his rock. “I’ll come back with a cart to collect the cask of wine you owe me.”

“You can collect the beating I owe you as well,” Samaki said bitterly as he began arranging the pieces on the left side of the grid in alternating positions. “I suppose I should thank him for taking that accursed wine from me,” Samaki muttered under his breath.

“Come, Hamota,” Tiyharqu motioned towards him. “I’ve lost my audience. Let me walk with you so I have someone to listen to my talk.”

“Your company would be welcome. I may need a big woman like you to help me lift all that wine,” Hamota clapped his hand around Tiyharqu’s arm, a friendly gesture, and the two began to walk away.

Samaki grabbed four flat sticks lying on the rock, one side painted black, and handed them to Tersh. “You know the basics, yes?”

Tersh nodded, taking the sticks. “The two of you were betting on the game?”

“It does make it more fun.”

Tersh studied his face. Samaki did not look like he was having fun. His mind seemed to be elsewhere. “Well, if it makes it more fun.” Tersh sat on the rock, putting her things next to her. She opened the skins just enough to reach in, her fingers rummaging through the trinkets until they found one of a suitable size. She pulled out a gold ring, a large emerald set on the band, and placed it next to the board.

“Ha, I’ve always believed a gamble with a Go-man is a dangerous thing.” He picked up the ring, letting the sunlight sparkle in the emerald, before putting the band in his mouth and biting. Satisfied, he put the ring back. “And if you win?”

“Maybe some of that wine?”

Samaki narrowed his eyes again, but then smiled. “If that is what you want, that is what I’ll wager. No one will buy it from me now that the Paref is dead.”

The game was simple enough, trying to get the pieces off the board by moving them around the grid until they reached the squares with the hieroglyphs on it. The first hieroglyph was three lutes, the next was three wavy lines representing water, the third was three ibis birds looking to the left, and the final hieroglyph was two figures leaning on one knee. The last square was blank. People always had different rules for what these squares meant. Samaki explained that to get the pawns off the board one had to reach the blank square, but first they had to land on the lutes. If they landed in the water, they had to return to the beginning. Landing on the ibis let you switch any two pieces on the board not on a hieroglyph, and if you landed on the kneeling man the other player couldn’t capture your pawns.

“It’s strange finding a Whisperer who can speak the tongue of Mahat so well,” Samaki commented, but his brow furrowed as he concentrated on the game.

“My tribe travelled here when I was very young. We stayed through many constellations.” Tersh was not thinking very hard about her next move. Already Samaki had gotten four pawns off the board while she had only managed two. Everyone has their own strategy for senet. If a pawn lands on a square with another pawn already on it, those pawns are switched. It was called capturing. But if two pawns of the same type are next to each other, they can’t be captured. Samaki always kept two pawns next to each other unless he was forced to move them apart by an unfavourable cast of the sticks.

“I’ve heard Go-men go crazy if they leave the desert for too long.”

Tersh laughed. “I’ve heard the same of merchants who are on the sea too long.”

Samaki smiled. “But that’s true!”

“This is my first time to Sareeb. Are you from here?” Tersh asked.

“No, I…” Samaki’s face darkened. “My village is gone, wiped away as though it never existed, and all those who lived there…”

“I’m sorry,” Tersh was worried his mood would sour and he’d dismiss the Whisperer before she’d had the chance to bargain with him.

Samaki let the sticks fall, one dark side up. “Three.” He moved his piece from the ibis off the board. “I win,” he grabbed the emerald ring, slipping it on his finger.

“It suits you,” Tersh smiled but was trying to look disappointed that she had lost.

“Winning suits everyone.”

“Do you have any more emeralds in that bag of yours?”

Tersh opened her skins again, this time looking for something a little larger. She pulled out a thick gold bracelet, a Mahat symbol carved into the middle. “Well, it isn’t an emerald, but I’m sure it will do.”

Samaki didn’t check it this time. “I’m sure it will. And I’ll give you my finest cask of wine if you win – I certainly won’t let that lizard Hamota have it.”

“No.”

“No?” Samaki raised his eyebrows. “Something else then?”

“Yes. I’m seeking passage north, to Nepata,” Tersh tried to keep her face calm, worried the slightest change in expression would anger the man. “And you can keep the bracelet, as payment.”

“Passage north? On my ship, you mean?” Samaki’s dark garnet eyes opened in slight disbelief at the cloaked woman’s gall. “I’m not certain my men would be able to stand the smell.”

Tersh felt her face flush with heat. “If your men could smell anything over their own stench, I’m sure that would be true.”

Samaki was silent a moment, staring very intently at Tersh. She began to feel uncomfortable. Finally, he spoke. “Very well. If you win, I’ll take you.”

“Me, and mine.”

“Of course, you and yours. You can bring your smelly bag as well.”

“Let’s play,” Tersh said, and Samaki let the sticks fall.

Tersh was focused this time, and began moving the first two pawns only.

Samaki smile. “I shouldn’t give you advice, but I like to watch an opponent lose with dignity. You shouldn’t leave so many pawns behind, they become weak.”

“If I try to move them all together, they are slow.”

Samaki was several paces back, trying to organize his pieces like a snake on the board. “Go-men just don’t understand the importance of standing together. You’re a scattered people.”

Tersh smiled, her first pawn landing on the lutes. “Yes, but we come together when we need to.” On her next turn she moved her second piece to the blank square next to the lutes.

Samaki laughed. “Clever, a blockade. But you’ll have to move eventually.”

“Eventually,” Tersh began to grin. By capturing his pawns to get by them, Tersh’s remaining three cones were already lined up next to each other. Then she began to leap frog two towards the hieroglyphs.

Tersh couldn’t keep the blockade. In senet, if you can move a piece, you must. She got two pieces off the board, but then her third piece fell into the water and had to move back to the beginning. Samaki took over the blockade and managed to get three pieces off, but then Tersh got two more, and Samaki another. Then they were tied. Samaki’s final piece was on the lutes.

“You can have all the strategies you want,” Samaki quietly remarked, maybe only to himself, “but in the end you have no control over your pawn. It goes where the sticks tell it.”

He dropped the sticks, three dark sides up. “Damn.” He moved forward one square and into the waters. He went back to the start.

“We’re at the mercy of the gods,” Tersh landed on the lute. Samaki was catching up. Then, Tersh moved two spaces to the ibis, and finally tossed three. “But sometimes the gods are merciful.”

Tersh thought Samaki would be angry, but he smiled at the Whisperer instead. “The gods whisper to you. You have an unfair advantage. But,” he reached out and took the bracelet. “A deal is a deal. I will take you to Nepata.”

“Me and mine.”

“Yes, yes, I already-”

“No, I don’t just mean my bag, but my son, too.”

Samaki laughed out loud. “Never gamble with a Go-man! Why don’t I listen to my own advice?”

“A deal’s a deal.”

“Yes, you and yours can come. But, this,” he held the bracelet up, “is payment for one. I hope you have another bracelet in there.”

“I do. Give me a price. I shall pay.”

The greed in Samaki’s eyes was obvious. They seemed to glitter like the gold bracelet he held. It was worth no more or less than any of the trinkets he wore, but to a man like Samaki there was never enough gold in the world. They always wanted more. They would even help someone they found distasteful if it meant their purse grew heavier.

“You and the boy can come, but we have no food to give you, you must find that yourself as well.”

“We are the Whisperers of the Gods. We can feed ourselves.”

“Good. We leave tomorrow, once our business is concluded here,” he held out his arm and Tersh only hesitated a moment before reaching out, the two clasping each other’s forearm.

“Thank you, Samaki.”

“You can call me Captain, and before you get on my ship, you better both bathe.”