NO ONE WILL BELIEVE A LIAR’S WARNINGS

Samaki was smiling so wide his cheeks hurt, but he dare not let his face drop. He was furious, and he would have loved nothing more than to have lashed out at the guards who had spoken to him as though he were some common peasant. He had been coming to the Paref’s palace for years, trading and enjoying the Paref’s favour. But, he thought darkly, the old Paref was dead.

Paref Rama was the fifth of his name, an old man nearly fifty-years-old, who had grown robust and drunk. He had reigned for nearly twenty years, Samaki realized, and perhaps his death shouldn’t have shocked him as much as it did. The truth was when he had heard the news in Sareeb he had felt as though a bee had stung him in the eye. Samaki had made a large fortune from trading the savoury grape wine of the Sephian Islands to the Paref. Most in Mahat loved beer, or perhaps the honey wines from the lands north of Mahat. Most of his stock was wine, and he was not entirely certain he could sell it now.

He could still remember the first time he had come to the palace. It had been around three years ago. He had been selling wine to the Paref long before that, but always through one of his agents. He had taken his ship to the same golden quay it lay at now, meaning to unload his casks of wine. He had never dared step onto the plaza, though he would often stare enviously at the lords and ladies walking by, laughing to themselves, lounging in the gardens while musicians played delicate instruments.

“A merchant can be as rich as a Paref, if he’s smart enough,” he could remember telling his father that the day he had told him he would no longer go out and collect papyrus reeds or fish or hunt with him, that he was going to leave the village of marshmen and strike out on his own.

His father had laughed at him.

“A smart man wouldn’t leave a good home and a good life. You’re a fool, just like your mother. She always dreamed of silks and silver,” he said bitterly.

Samaki had never known his mother. She had caught fever after giving birth to him and died shortly thereafter. Whether or not she ever truly had those dreams, he didn’t know, but his father despised such talk.

“When you’re sick of starving, you can come back,” he had nodded, going back to gutting and cleaning the fish he’d caught that day. He hadn’t even bothered to look up as Samaki had left.

He wouldn’t go back poor and starving. He refused to. He did starve, and he was poor – at first. There were many times he did think of going home in defeat, but his father’s cold laughter rang in his head. The next time he returned home he wore a gold medallion around his neck, and around his waist he had tied a blush silk belt. He thought he would see pride in his father’s eyes, or the realization that Samaki had made the right choice.

His father only laughed again. “Rich as a Paref, eh? I can waste what I earn on silk too, but I’d rather eat.”

Samaki had never pleased his father.

With a pain he remembered again how he never would. There was no village, there was no reed boat. It was all washed away. The little mud hut he had slept in, his childhood friends, his father… He pushed the thoughts away, swallowed them deep. He had no time to mourn, not when his position hung so precariously. The only thing that mattered was selling the wine. If he couldn’t, he was in trouble. He would need to go to silver-lenders to fund his next voyage, and he knew once he fell into debt, he would never climb out of it. The silver-lenders were skilled at making sure no one did.

Every night since learning the news he had prayed to the gods Afeth and Baph that this new Paref Rama had the same tastes as the Paref before him. In Sareeb he had even visited a temple dedicated to Afeth and left an offering of some of the wine he meant to sell – giving it away seemed a trivial matter if the new Paref rejected him.

“Tell me of our new Paref,” Samaki said pleasantly, still straining to look happy through his anxiety. They walked across the massive stone plaza towards the entrance of the palace. It was called the Palace of the Rising Sun, and had been home to the Parefs since the city at the base of the mountains now called Hattute was abandoned by the people of Mahat. The entrance of the palace was massive, with two black obelisks on either side inscribed with golden hieroglyphs. The palace behind them was called the Palace of the Setting Sun, and the only difference on the exterior was that their obelisks were red. It was home to the King of the Mountain Mahat, though Samaki had never traded nor met with him.

The man who had come to them on the docks was named Imotah, the tzati of the Palace of the Setting Sun, and so in charge of everything that happened within its walls. The tzatis were only second to the Paref in true power. They received their positions not only from their intelligence and wisdom, but their knowledge of spells and potions. More importantly, they received the positions by being related to the Paref. Imotah was the youngest brother of the fourth Paref Rama, and he was a few years younger than his nephew the fifth Paref Rama had been.

Imotah had the features Samaki now associated with the royal family, the weak chin and elongated head. He could still remember the shock and disappointment he had felt when he first met a member of the royal family. He had imagined shining men and women of indescribable beauty. Fishermen’s daughters looked more pleasing to his eyes than the ladies of the palace.

Tzati Imotah was tall and chubby, but his eyes were too close together and his nose too big. He wore a plain wig, the hair cut to shoulder-length with straight bangs, as was the usual style, and on his chin he wore a braided beard that stuck out like a horn. The old Paref had looked much the same, except for a larger girth. The only time he had ever seen an attractive royal was when the bride came from outside the palace walls, but even then beauty was not assured.

“The young god is a splendour to behold. He is the sun and beacon of hope in Mahat,” Imotah extolled, his voice dripping with sarcasm as he smiled at Samaki. The jest made some of Samaki’s anger fade away and he smiled more easily.

The women, who had moved to walk behind them, giggled. The melting lumps on their wigs were only worn of the hottest of days. As they melted they released incense to mask the smell of sweat from walking in the heat all afternoon. It was sickeningly strong. Samaki wondered if they were Imotah’s daughters. What he knew for certain was that they were related to the man somehow, their weak chins and buck-teeth gave it away. The palace was a tangled spider-web of inter-family relations.

“Young… A boy then?” Samaki could not remember having met him before. The old Paref had sired many sons, but only one by his High Wife, and Samaki had no doubt she had ensured her son’s succession would be swift. He had only seen the High Wife Djeperu a few times, always at the Paref’s side. She always had an air of command about her, and Samaki felt it would be wise to stay in her graces. Samaki knew her first child had been a girl, and had one of the sons of lesser wives who were older and stronger than her own marry that daughter. Those other sons might have been able to wrestle the throne from the current Paref, if Djeperu wasn’t standing in their way.

“Not in swaddling clothes, thank the gods. He has seen fourteen years, so he is a man,” Imotah stretched the word out, as though he didn’t quite believe it was a true fact.

They entered the palace. Guards looked at them wearily, but allowed them to enter. The massive palace walls were just that, only walls. Inside the true size of the palace was revealed. It was only two storeys high. It was not the height of the palace that was impressive though, it was how much sprawling it was. The palace spread out like a great labyrinth, beautiful engravings painted over in bright colours showed the first Paref Rama’s great victory against the kingdom of Matawe. He drove a chariot, wielding a bow, hundreds of men lying dead by his feet, the massive amounts of spoils being depicted went on and on, past the point Samaki could see.

“You lovely jewels go frolic by the cool pools. It is too beautiful for you to come into the dark palace.” The girls giggled once more and did just as Imotah suggested, taking their walking shade and going back the way they had come.

Samaki followed Imotah into the palace. The first chamber was filled with rows and rows of giant columns, each one so large it would take five grown men holding hands to encircle one. There was no rooftop and the sun lit up beautiful tableaus of Parefs and their wives and children enjoying the nature of their gardens. From that chamber they entered a long corridor, this one with a roof. Despite the corridor’s many windows, it was much darker compared to outside, though also wonderfully cool.

“How did the Paref die?”

Imotah shrugged. Despite their constant intermarriages, there was not much love between the royal family members. “Too much wine? Too much food? The Paref did not care much for his health in his final years. My doorkeeper says he died mid-thrust in his youngest wife, Nifer. They had to carry him from the harem on a litter.”

“Only a god would end life so blissfully,” Samaki smiled, feeling a slight pang of jealousy.

At the end of the long corridor, a few narrow halls opened up to them. There were no markings beyond the painted frescos, but Imotah had walked these halls his entire life and knew exactly which one to go down without even thinking. The corridor they chose was narrower, and Samaki could see the light of day at the end. Samaki had been to the palace many times before, but he had always been led by someone, and wasn’t sure he’d ever find his way through the halls by himself.

“It was a good day to come,” Imotah explained. “The Paref was legitimized as the reincarnation of his father yesterday, so today all the tzati and djoti have come calling in order to ensure they still have their positions. Otherwise, you may not have found the Paref on his throne accepting guests.”

“I appreciate finally getting a taste of luck,” Samaki sighed.

They exited onto a large courtyard twice of the size of the plaza, but instead of stone, the courtyard was covered in plants and dotted with cool pools of water where ibises rested and small pink flowers floated. Along the sides of the courtyard were more columns painted bright gold and red, and between them countless doors leadings into the many chambers of the palace. They went to a door on the far side of the courtyard, passing by pageboys and other lords who gave courteous nods. Samaki stared at their wigged heads. He could understand their desire to shave off their hair. Hair was a dirty thing in such heat. Why they bothered to then wear decorated and styled wigs was something he simply did not understand. He found the fake beards the lords all wore particularly amusing.

The door to the throne room was no larger than any of the others, but inside there were long steps leading up and the frame was golden. Up the steps they went, into a high roofed hall. There were massive tall windows, rose silk draped over them, gently blowing in the wind. The room was cool and inviting, and it was packed with lords and ladies. On a high dais of golden steps was the throne. The chair was so large the boy who sat in it looked like a tiny doll.

He may have been fourteen-years-old, but Samaki would have sworn he was only ten. He looked sickly thin. He barely had a chin, and even the pointed black beard tied to his face with golden string could not hide that fact. His pointy face and tiny eyes made him look more like a mouse than a man. The top row of his teeth jutted out of his lips. He was dressed in an extravagant golden silk robe, wrapped around his body and over his shoulder, and on his head he wore the Paref’s golden nemes. The brow of the nemes was embossed with both the golden head of an eagle and a man wearing a feathered hat. It was so large it threatened to consume his tiny head.

On either side of him were tiny wooden benches. On his right was the familiar face of Djeperu. She wore a simple pure white linen dress, adorned with a thin red beaded belt, and on her black wig sat a thin golden band. She wore the clothes of the Paref’s Mother. Despite the simplicity of the dress, with her piercing black eyes and high cheekbones, she still looked far more regal than the young girl less than half her age on the left of the Paref.

The young girl looked to be about fourteen as well. She had a beautiful round face with wide dark eyes, and beneath her sheer white dress he could make out the dark circles of her nipples. She was covered in more jewels than the giggling girls who had been following Imotah. At her neck was a thick necklace in the shape of a bird made entirely out of rubies, and her wig was made from golden thread.

Next to the seated figures were young girls wearing tunics and plain black wigs, holding long fans shaped like palm fronds, dutifully moving them in rhythm with each other. At the foot of the dais stairs, and indeed all around the room, stood broad-shouldered guards. Moving through the crowd of lords were tunic-clad girls holding golden trays topped with fruit. There were many waiting to speak to the Paref, but Imotah cut to the front of them, interrupting a portly fat man who was grovelling before the throne.

“My lord Paref and dearest nephew,” Imotah said loudly, a lovely smile on his narrow face.

“Uncle,” Rama smiled, and it was an ugly sight to see his large teeth emerge from his mouth. The beautiful woman to his side looked straight ahead, seemingly not wanting to acknowledge anyone in the room, but Djeperu held Samaki’s gaze. “Have you come with more gifts?”

“Always, beloved nephew,” Imotah bowed low. “And my lady, the Paref’s High Wife. My lords, I present to you the glorious merchant Samaki, who was loved by your father. Samaki, behold the opulent Paref Rama and his High Wife, the southern Princess, eldest daughter of King Utarna of the Sea Mahat, Merneith.”

“My lords,” Samaki put on his most charming smile, bowing as low as his body could bend.

“Rise, merchant,” Rama commanded. He had a weak voice, Samaki realized. It seemed the gods hadn’t been willing to offer the boy any gifts when he was born, save for his father’s name. “I fear my father’s memory died with him, but his spirit resides in me now, and I’m sure the love he felt for you dwells in me now.”

Djeperu leaned over and whispered something into her son’s ear before he continued. “Yes… Samaki. I have heard the name. It was said you could produce the finest wine in all the world from the hold of your ship.”

“Of that I know not, but the Paref Rama before you loved well the wine I brought for him.”

“Yes, that is good…” Rama looked bored, and his eyes turned away from him to stare at the Princess Merneith at his side with longing. Samaki was losing his attention. Imotah gave him a look that said he could not, or would not, help him beyond this point.

“I was most grieved to learn of Paref Rama’s death when I arrived in Sareeb. The gods, it seemed, were horrified as well, for they sent a great wave throughout the Sea Mahat, no doubt it was their endless tears at his loss,” he tried to sound light-hearted, but his voice twinged as he spoke. They loved your father so much, they had to take mine in his stead.

“Yes,” Rama turned back to him, his face troubled. “I have heard of the flood. It was unfortunate of the gods to do that. But when the Paref’s soul wanders, Afeth runs freely.”

Afeth. His ship was named for the god of chaos, but Samaki did not bother saying so aloud.

“As it happened, I was in Sareeb because I was returning from Serepty with my ship’s hold filled with the grape wine Paref Rama loved so dearly. If you are soon to be crowned, I would be honoured to sell you all I have for your great feast.”

“Sell?” The Paref’s Mother looked annoyed and Rama followed suit. Obviously having been given gifts all day, the boy was expecting the same from Samaki.

“It loathes me to sell and not give, aye, but I fear I cannot afford to give it freely, as much as I wish to. The most I can do is offer it at a lower price than the glorious Paref Rama offered me, for I must hire new men and, indeed, must feed my family,” his voice seemed to lower at the last word. What family? His family was gone…

Djeperu leaned over and whispered something else to her son. She had never been so bold with her husband in front of his subjects.

“I am not interested in special favours,” Rama said, and Samaki felt his heart drop in his chest. “I will buy your wine, and pay the price same as my father, to honour him at my wedding feast. Instead, you may give me another gift.”

Samaki looked at Imotah uncertainly, but the tzati seemed to have no idea what the boy meant either. “Oh, and what gift may a lowly merchant such as I give to a great Paref ?”

“I have decreed one of my duties as a new Paref is to show my enemies and allies alike my grace and power. I wish to send tribute to the great kings of the lesser kingdoms. I would have use of your ship.”

He couldn’t refuse, he knew that. If he refused the boy wouldn’t buy the wine, and if he didn’t sell the wine, he might as well sell his ship. He forced his smile. “And where would you have my ship sail?”

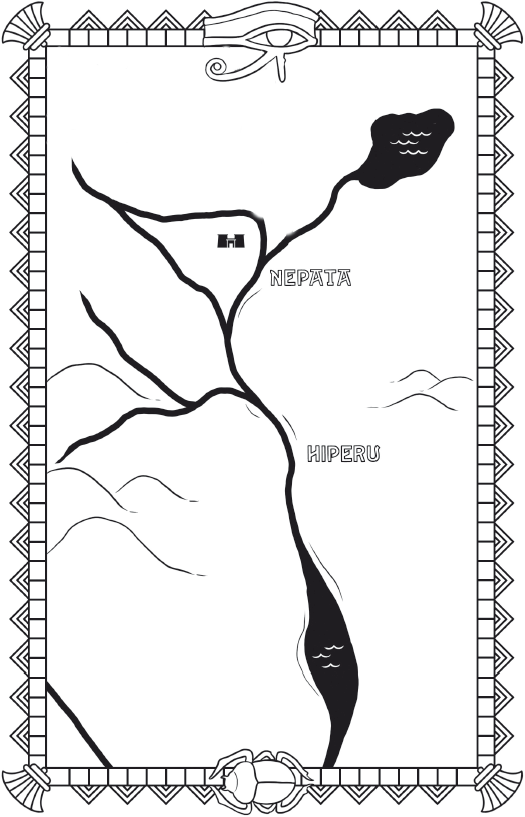

“I would have you sail north to Hattute, the city nestled at the base of the mountains. I wish to honour King Hatturigus, apparently the sixth king of that name to rule there. They call him King Under the Mountain.”

Samaki had heard some of the tales about the wars in the mountains, where there ruled two kings, the King Under the Mountain in Hattute, and the King Over the Mountain who lived in the high peaks of the city Nesate. There were also stories of five Queens or, some said, five witches, who wished the tear the kingdom asunder. The constant wars in the mountains had kept him from ever sailing there before. There was not much profit for a merchant who did not peddle weapons in war-mongering countries.

“Nothing would please me more than doing this for you, my Paref,” Samaki bowed again, this bow decidedly not as low as his first.

“Imotah, see to the arrangements,” Rama waved them away and they stepped aside.

The fat lord they had cut off earlier glared at them, but turned to the Paref with a smile. “As I was saying…”

They left the throne room and went back out into the courtyard.

“Did you know he would ask me to do that?” Samaki turned to Imotah.

“I honestly had no idea,” Imotah smiled, and Samaki couldn’t tell if he was lying, or what the man would have to gain from being dishonest. These people bathed in lies. Samaki thought they often forgot they could tell the truth.

“Why even ask a merchant to carry tribute to a king?” Samaki was already beginning to calculate how long it would take and how much it would cost. Would he have enough space in his cargo to carry goods to trade? Otherwise he would lose too much on the trip.

“I suppose, like all the Parefs before him, he would rather spend his gold on jewels and feasts instead of state matters. He is only sending the tributes because his mother insisted he do it. New rulers are always seen as being weak until they prove themselves, either in friendship, or through warfare. My noblest nephew is not a warrior.”

Samaki was glad at least to have solved the problem of selling the wine. Now he would just have to make the exchange and hire new crew for the journey north. And what of the Whisperers?

“That reminds me,” Samaki said as they left behind the courtyard for the dim hallways that led to the palace entrance. “I travel with two… people. They wish to speak to the Paref. They are holy messengers, and they believe they have an important message to share with him.”

“We get more holy men than we can count. They are a bore, and I doubt my shining nephew wants to be bothered by them.”

He knew he owed the Whisperers nothing, but he had grown a fondness for Tersh. They had often played senet and talked during their journey north, and he wanted to help her and her son if he could.

“Come back to my ship and meet them. Decide for yourself if they’re worthy to go before the Paref.”

Imotah shrugged. “Very well, I had no other plans this afternoon. I have often thought of you as a friend. It would be my pleasure to help you.”

Samaki knew it would also be Imotah’s pleasure to be owed a favour.

When they returned to the ship, the Whisperers were instantly on their feet, anxious looks on their faces, while the other crewmembers only looked on with mild interest. Samaki and Imotah walked up the gangplank.

Tiyharqu greeted them at the top. “Captain,” she nodded, then turned to Imotah and bowed. “Gracious tzati. You honour us with your presence.”

Samaki pointed to the Whisperers. “These are the holy messengers.”

“I thought they’d be men, not a woman and a child. This one’s younger than the Paref,” Imotah almost laughed. Looking Kareth up and down.

“But he certainly looks older,” Samaki muttered.

“Can we go before the Paref ?” Tersh asked.

Kareth looked at Imotah, his silver eyes shining, and Imotah was taken aback. He grabbed Kareth’s chin, looking long and deep into his eyes. “Never in my entire life…” he whispered to himself.

Samaki could understand Imotah’s reaction. Him and his crew had often talked about the strange silver eyes. He had never seen eyes like those on the men of Mahat, or even in Serepty, where eyes could be the pigment of water or a cloudy sky. Once he had seen a woman with the shades of leaves behind her lashes, but never silver. No, the only time he had seen eyes like those was when he had met a Rhagepe once. He heard all Rhagepe had silver eyes like those. He had imagined only the sand witches had them. Most of the crewmen were weary of Kareth because of those eyes.

Kareth jerked his head away, turning towards Tersh with an annoyed expression.

“Dage ki karlai thenu morikah tomech mo hothomeiru?” He muttered angrily, and Samaki could only imagine he hadn’t made a kind comment.

Imotah’s eyes narrowed. “Just where do you two come from?”

Tersh looked at Samaki uncertainly.

“No one will believe a liar’s warnings,” Samaki cautioned.

“We come from the desert,” Tersh answered slowly.

Imotah’s eyes widened. “Go-men?” He turned to Samaki incredulously. “You sailed all this way with Go-men on board?” He sniffed the air. “I thought they all smelled like blood and decaying corpses.”

Tersh looked angry, but Samaki tried to smile. “I made them bathe,” though in truth he sometimes thought they smelled better than most of his crew. “These are good people. Though the young one is slightly troublesome at times…” he laughed, and Tersh was forced to smile.

“The Paref will never agree to see Whisperers,” Imotah said simply.

Kareth looked eager to know what was being said, and when he saw the disappointment on Tersh’s face, he began to tug on her cloak and ask her a question in their tongue. Tersh pushed him away.

“We speak for the gods. He will see us,” Tersh insisted.

Imotah laughed. “Paref Rama is a god,” though Samaki knew the man did not believe his own words. “He can speak for himself.”

“The flood in Sareeb is only the beginning. Terrible things will come to pass unless we can warn the Paref,” Tersh spoke carefully, her voice lowered; her eyes seemed darker.

Samaki knew Imotah was not a superstitious man. Nevertheless, there were too many stories of terrible things happening to men who had been cursed by the Whisperers to be ignored. Curses sent by Whisperers had brought down some of the mightiest Parefs. The city of Hattute had been built by the sixth and last Paref Amotefen, who had hunted down and slaughtered every Whisperer he found within the border of Mahat. Amotefen was killed by his own cousin, and his great city fell to a prince from the kingdom of Matawe. Since then the people of Matawe had constantly been at war with each other because of that city, because it had been tainted by Whisperer blood.

“I honestly don’t know how I can help you. If I bring you two before the Paref, he’ll strip me of my position – or even my life. And, he’ll ignore whatever you have to say. It would take years of convincing before he’d ever consent to be in the same room as you.”

“The flood is not proof enough?” Tersh asked incredulously.

“A hundred floods would not be proof enough your gods held any power in Mahat,” Imotah waved a hand at her dismissively.

“Perhaps you can convince the Paref to see you in time,” Samaki said, feeling strangely guilty that he could not stay and help them longer. “I need to leave soon and head north to Hattute, the city at the base of the mountain. I won’t be able to help you from there.”

“The mountains?” Tersh looked surprised. “I need to go there, and speak with their king.”

“It seems you need to speak to every king…”

“No, he needs to speak to the Paref, my mission is to speak to the ruler of the mountain. We only travelled together because our paths were the same.”

“What do you mean that’s the only reason you travelled here together? What are you saying?” Samaki narrowed his eyes at him.

“I must follow the river north,” Tersh hesitated only a moment before her face became resolved. “Take me with you,” she looked at Kareth with a pained expression. “I cannot waste time here in Nepata.”

“You’d leave your son here?” Samaki was surprised. Were Whisperers really so cold?

“He’s not…” Tersh trailed off.

“He’s not your son, is he?” Samaki chuckled. “You and yours indeed. I swear, the more you fool me the more I like you. You Whisperers are as slippery as fish.”

“What was that you said about liars, Samaki?” Imotah asked in an amused voice.

“He’ll find no help here,” Samaki looked at the boy piteously.

“He cannot come with me… He must follow the gods. We all must. The sticks fall, and the pawn moves. Isn’t that so?” Tersh looked at Samaki with the face of a defeated woman.

Imotah smiled sweetly. “He need not starve. Any house is always in need of a servant. I think my stables could use another boy.”

Samaki eyed him warily. He was uneasy of making any deals with the tzati. He seemed as trustworthy as a money-lender.