I NEED NOT FEAR THEIR CURSE

Every day Tersh asked for another audience with the kings, a private one this time. She hated how she had been treated like some entertainment before, some exotic toy to bemuse them. She walked through the stone halls, wanting everyone to see her presence, to remember the one who spoke for the gods was still among them. She practiced over and over what she would say in her head. She would not plead next time. She would not get overly emotional. She would let the words of the Goddess of Death flow through her. If death could not convince them, nothing could.

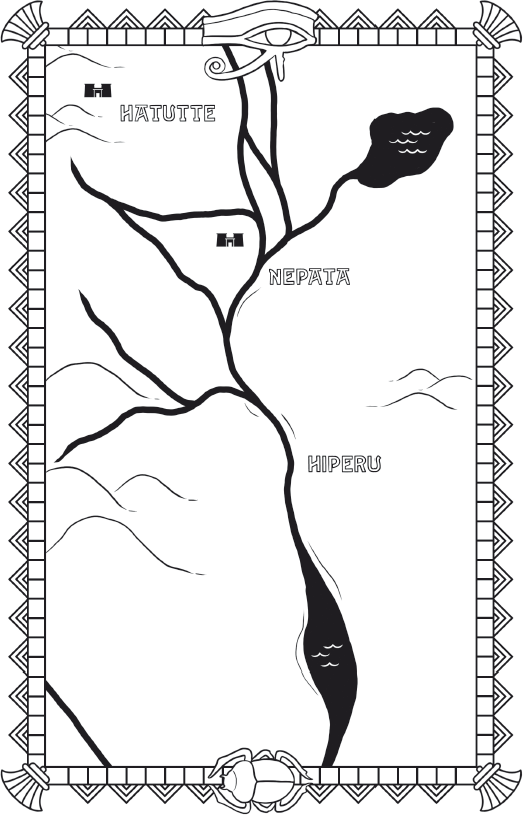

Her requests went unanswered, either because they were ignored or simply not delivered. She grew more anxious each passing day. Samaki was already making plans to set sail back down the Hiperu. The captain had sold all the wares he had brought with him and had bartered several more things to sell. The merchandise of Hattute mostly consistent of wool, or copper from their mines, but their prize export was precious jewels. Still, most of what Samaki chose were weapons.

“The two things men need most are food and weapons. Hattute has no food to spare, but they have more weapons than soldiers,” Samaki had said as he oversaw the packing of his ship’s hold.

Food and weapons. It seemed a cynical thought to Tersh, but she couldn’t deny it. If a land had no food, they needed weapons to get some. If a land had unlimited food, they needed weapons to protect it. The Whisperers were not a warfaring people, but even they always kept weapons on hand.

Watching Samaki make preparations to leave made it all the clearer to her that she was running out of options. A part of her was still tempted to return with Samaki, to leave these fools to perish in the mountains, but she feared the consequences of that action. She could try to stay and convince the kings, but as the days continued to pass that thought felt more and more futile. So the other option was to take the pass up the mountain, to the city called Nesate, where the queens, and the cause of the civil war, resided. But even that option wasn’t available to her.

The weather had changed since coming to the foot of the mountains. At first it was just a strange chill in the west wind. Tersh had felt cold before, the nights in the desert could freeze you to the bone, but with a fire and a warm body next to you it was easy to deal with. This cold stabbed at her. Her cloak did nothing to protect her, and she felt herself shivering all the time.

“This is nothing,” Tiyharqu had laughed. “A little wind. In the mountains they have snow enough to bury entire cities.”

Samaki was determined to leave before the snow. Snow. It was a new word for Tersh. Rain was a rare thing in the desert, but it was something she was familiar enough with, especially from her childhood in the Sea Mahat. But snow? When the winds grew so cold the rain itself froze. Apparently it only happened high, out of reach of the Hattute. The higher you went the colder it became. When it happened the streams stopped flowing into the Hiperu, and the waters became so shallow a ship would become grounded.

The captain had given her a tunic and a set of woollen boots to help keep her warm. She appreciated the gesture, but even that felt like not enough. Winter was coming, and until it passed, the mountain pass would be closed to her.

“Return to Napata with us,” Samaki offered. “Come back in the spring.”

“I doubt any other ship will bring me back,” Tersh had frowned.

“I’m sure you can trick some other poor captain into taking you,” Samaki grinned.

“I’m not sure there are any other captains as gullible as you.” Tersh couldn’t help but grin herself, and Samaki had laughed.

And then came a day when the ship’s hold was full and Samaki was ready to set sail. The days were crisp with cold wind, but with the sun out it was still warm enough for Tersh to manage. Tersh asked if it would get much colder as the mountains above them froze.

“Take the coins, Tersh,” Samaki offered the modest purse once more as they walked towards the quay. There was a lot of activity at the docks, since the Afeth was not the only ship trying to leave before the water levels dropped too much. They could just make out the Afeth among all the other ships where Tiyharqu was taking a roll call of the crew. She stuck out, being the largest ship there.

“I’ve done nothing to deserve it,” Tersh said, uncomfortable with taking charity. She tried to give Samaki some of the jewels she still carried with her, but Samaki refused that.

“You’ve beat me at senet so many times I’m sure you deserve this and more,” Samaki held the purse out to her once again.

“I have enough to trade, I don’t need your silver.”

“It’s mostly copper,” Samaki winked. “These coins hold no meaning in Mahat. They’re useless to me there. Anyway, your treasure will serve you well enough, but men who realize you carry it with you may try to take it. Better to use coins, to avoid being cheated. The men here are cold, just like their winters.”

“I thought you said no one would hurt a Whisperer here.”

“They fear Go-men here, that’s true, but they fear starving more. I tell you, this country is sick, and the winds and the wars starve them into doing terrible things if they have the chance.”

Tersh hesitated a moment longer, before reaching out and taking the bag. It was light, probably just enough coin to make it through the winter. “Thank you,” she muttered, slipping it into the opening of the skins she carried. “Will you check on Kareth when you’re in Nepata?”

“I’ll try to see him,” Samaki said.

Tersh shot him a concerned look.

Samaki sighed and added, “I will make sure to enquire about his well-being, and I’ll make sure he knows you arrived here safely.

“Don’t worry about the boy,” an older sailor walked past carrying a large vase. It was Sef, the man who had saved Kareth from the river when he had fallen overboard.

Tersh looked away. Maybe she should return to Nepata, just to watch over the boy. She shouldn’t have left him so soon, and she wasn’t much use here. Surely she could find another ship back here come spring… No, she shook her head. She couldn’t give in like that. She needed to be strong, for Kareth, for herself… for her family. She knew if she left now she wouldn’t stop until she was back in the arms of her family.

“Will you ever return this way?” Tersh asked, hopefully.

Samaki was quiet a moment before answering. “I can’t honestly say I will. This country is not ideal for a merchant like myself. I never truly know where my next port will be, but it’s always possible. Hopefully, you’ll take my advice and the next time I come here you’ll be in Nesate.”

“I can’t imagine I’ll have better luck with them,” Tersh muttered glumly.

“Kings and queens, it makes no difference. Rulers are all the same. They all want to hear how wonderful and important they are. If you make them believe they’re the only thing standing in the way of the wrath of the gods, they might listen just to make themselves that much more important,” Samaki grinned.

They boarded the ship, and Tersh stayed on the wooden pier, watching the young sailors unfurl the sails and helping to untie the leads, to break away from shore. Samaki called out to her one last time, a spear held in two hands. He tossed it down to Tersh, who caught it smoothly in both her hands. Feeling the wood on her palm reminded her of the journey through the sea of sand with Kareth. She hadn’t thought much of the spear Ka’rel had given her since joining the Afeth. It somehow seemed heavier than it had before.

“Watch your back, Go-man!” Samaki said, with a final wave and a laugh.

She imagined Kareth must have felt the same way, watching the Afeth start to drift away, being left alone in a foreign land he knew nothing about. The fear she felt was so palpable that she could taste it, a bitter stinging taste. Her throat seemed dry. She wanted to call out to them, but she didn’t know if it was to say farewell one last time, or beg them to take her. She remained silent, unmoving, watching the ship disappear, her vision blurring over for a moment.

When she knew they were far enough that even her shouts wouldn’t reach them, she felt a strange sense of relief. The choice had been robbed from her, and now she would have to stay. Now she would have to follow the path the gods had made for her. She would stay the winter here, trying to convince the kings to hear her. Come spring, her goal completed or not, she would head higher into the mountains to see the queens in Nesate.

It felt good to finally know what needed to be done, even if it wasn’t what she wanted to do.

She turned back to the city, noting that the sun was hanging low in the sky. The gates would close at nightfall, and she knew spending her night out here in the cold would be more than she could handle. As she walked she let the butt of the spear fall on the ground, using it much like a walking stick.

People had been staring at her wide-eyed since she came here, but for some reason she noticed it more now. When she had been with Samaki or the others she could ignore it well enough, or simply hide from view behind one of the crew, but now being alone the stares seemed all the more intense. Whether it was hatred or fear or both, she couldn’t honestly tell, but she despised it.

The guards let her pass through the city gates without problem, their eyes following her. When this city was being built by the men of Mahat, a thousand Whisperers had been slaughtered, bronzed alive, cursing this city for all time. They looked at her as though she carried the curse on her back, as though if they came too close or gave her any problems they might catch it. It made her feel as though her cloak were a shield protecting her.

She felt like she was lost in a dream as she walked back to the palace. She felt like she was floating through the streets, so disconnected from everything that she couldn’t even feel the ground beneath her feet.

The damn boots, she smiled at the thought, looking down at the boots Samaki had given her. They cut me off from the earth.

When she reached the second gate, leading to the Hall of a Thousand Gods, the guards did not step back to let her pass, but instead looked at her with uneasy glances.

“You cannot pass,” one of the guards managed to say through a thick accent. It was obvious he couldn’t really speak the tongue of Mahat, but had simply learned a few sentences to help with his post.

“Why not? What’s going on?” Tersh asked, feeling a sudden unease. There were a few people, servants and guards, walking just beyond the gate, within earshot, but obviously trying to avert their glances.

The guards looked at each other, one of them shrugging ever so slightly, as if indicating that he couldn’t understand what she was saying either.

“Is it my spear?” She pointed to her spear with her free hand. It was true she hadn’t tried to enter their halls armed before. It might be making the guards overly cautious. “I can leave the spear with you. I don’t need it inside.”

There was a pause, the guard looking more distressed. “You cannot pass,” the guard repeated, shaking his head, his eyes looked more frightened than intimidating. Tersh felt like she could have just pushed past them and they wouldn’t have done anything to stop her.

There was no point in trying to rush past them though. She tightened her grip on her skins. She had enough to trade and pay for another place to stay. There was nothing left for her there. If the kings would not see her, they damned their people, but she could go on to Nesate and then return again to this place. Perhaps if she had success in Nesate, convincing these fools would be easier.

She turned away, not sure where to go, but just decided to take whatever road she came upon. She took a bridge over the wide river that ran from the palace to the docks outside the walls. The city was closing down. Stalls were packing up their wares and shops were locking their doors for the night. The streets were mostly empty, only a few people here and there making their way home, most likely. The only noise she really heard came from the alehouses and inns. She needed to find one that would let her stay. She would have better luck, she realized, if she turned her cloak inside-out.

Tersh stopped to do just that, when she noticed that the street she was on ended in a large gate. It seemed out of place for a neighbourhood that the rich did not inhabit. The gate was massive, at least as tall as the buildings around it, either side of the entrance heralded by large statues of men. They held their arms out, their hands up, as though warning them not to enter this place.

There was just enough light left in the sky to catch a glimpse of what was through the gates, and Tersh was curious. She walked the rest of the way, finding it odd that such imposing gates had nothing blocking the entrance, neither door nor fence. Anyone could walk through, yet the street beyond was completely deserted. She came to the entrance, standing between the statues, but not daring to walk through them. The atmosphere seemed to change around her, a colder wind blew out, and she shivered as she saw what the walls surrounded.

It was a road. Three times as wide as the one she stood on, but the same road nonetheless. She turned around, looking back the way she came. The road led straight back to the Hall of a Thousand Gods. This road must have been a twin of the grand avenue lined with leopard statues, but while that one remained pristine and exquisite, this one had been abandoned to shop owners and innkeepers who needed more space, building onto the road, shrinking it to its current size, all save for this one portion which had been walled off and remained untouched.

She looked back through the gate, to the statues that lined the avenue. The other avenue had been lined with stone statues, but this one was lined with bronze ones. She couldn’t make out what the figures were at first. They seemed twisted, each one completely different from its neighbour. She didn’t need to guess what they were. She knew. The last rays of sun just barely glinted off what had once been the heads of a thousand Whisperers.

Tersh shivered, taking a step through and walking up to the closest of the statues. The man had been standing, his arms had been stretched away from his body, his legs spread apart. His face must have been looking up, for now his head seemed to crumple backwards. She could just make out the pained expression on his face, his teeth gritted, his eyes closed tightly, but the rest of the details of his face were obscured by the glops of hardened bronze. They must have poured the liquid metal over his head.

The air seemed to catch in her throat. She looked at the next one. This man had his arms and legs bound tightly together. Tersh could still see the chains wrapped around his body. He hadn’t been completely covered in bronze though. His head had lolled forward, and where his face had once been, the bronze had not entirely covered, and she could just make out the smoothness of his skull.

“I wouldn’t touch that. No, not I.” The voice was calm, but had a certain command to it.

Tersh pulled back her hand. She hadn’t even realized she had been reaching for the Whisperer, and turned around.

“Why not?” The last rays of light disappearing behind the buildings, but she could still make out the figure in the fading dusk. His hair was shoulder-length, sandy-black, and his chin had a shaggy light beard. She couldn’t make out his eyes so well, but they seemed dark whatever they were.

“Do you know why the gates have no door?” the man asked softly.

“It is not a forbidden place?” Tersh shrugged to appear unconcerned. She suddenly wished she were not standing within the gates anymore, but did not want to look like she feared standing among the dead of her own people.

“It is a forbidden place,” the man smiled, like he was telling a joke. “We need no door here, because every man, every woman, every child, knows this place cursed. They know only someone wishing to die comes here.”

“I am a Whisperer. I need not fear their curse.”

“No? Then why you look desperate to leave this place?”

Tersh realized she was still shivering, and started walking towards the gate, trying to keep as much distance from the man as possible. “I am merely too cold to continue standing here.”

“Ah, you need place to rest?” The man reached out, not grabbing her, but touching her shoulder to stop her.

Tersh shrugged away the touch, but stopped walking.

“Do you know of an inn?”

“One that would wish for a Whisperer of the Dead to stay under roof ? There’s no such inn at these parts. No, I’m sure every inn you visit will tell you that ‘oh so sorry,’ all their rooms are filled this evening.”

Tersh took off her cloak in one swift motion, then folded it up and placed it into her skins. She was instantly colder, and she hated having to hide it away. The thought suddenly occurred to her that she could take some of her skins and stitch them over the bones, but she doubted she had enough skins to spare.

“Why, you don’t look a Whisperer at all now,” the man said positively, but Tersh couldn’t tell if he was being serious.

“Goodnight. May the gods walk with you,” Tersh nodded, continuing on her way.

“Wait, wait,” the man followed. “My name’s Arzaia. What’s yours, friend?”

“I am called Tersh Hal’Reekrah of the tribe Go’angrin,” Tersh tried walking faster, but Arzaia seemed to easily match her pace.

“That’s quite long name. Is it all right if I call you Tersh?”

“How is it you speak the tongue of Mahat so well?” Tersh asked, wondering if this man was a merchant. She may have liked Samaki, but most merchants were interested in profit only and would take advantage of any situation they thought might benefit them.

“I often travelled there when younger. My father was a priest, and so I learned their tongue.”

“Your father was a priest? And what are you?” Tersh looked at the clothes he wore, a simple wool cloak, a hide tunic and leggings. The man wasn’t poor, but he didn’t look like well off.

“I work in the inn. I find weary travellers like yourself, help them find beds,” he pointed down a street, motioning them to follow.

Tersh looked down the avenue. It seemed wide and had many inns along it. She was suddenly weary the man might be trying to take her to a small alley to rob her, so she kept her distance as they turned down the road.

“Your family’s inn?” Tersh asked.

“No, no. My father was priest. I found work in the inn after I decided following the gods was not a path for me. Come, here.” He stopped by a building.

There was light and noise coming from inside, which made Tersh certain that it wasn’t an empty building, but did nothing to allay the thought that it was filled with men hoping to ambush her. She hesitated.

“I don’t have much to trade,” Tersh said.

“We make good price for you, friend,” he motioned again, perhaps a tad too eagerly.

“No, I think I’ll stay elsewhere,” she took a step back.

In the same moment Arzaia reached out to grab her and shouted a word in his own tongue. Tersh couldn’t understand it, but just then the door to the inn was thrown open and from it five men holding knives – and one a short sword – came out and rushed towards her.

Tersh barely had time to raise her spear to block the sword coming down on her. It imbedded itself into the wooden shaft, but luckily the spear held. Still, in another breath the others would be on her. She seemed aware of every single movement around her. One man’s arm being raised, another muttering some kind of curse-word, Arzaia slinking off into the surrounding shadows, the sword being yanked out of her spear so it could be used to come at her again.

She put one leg back, crouching down. She had never turned a blade on a person, but the motion seemed natural as she aimed the head of the spear at his sternum. The man’s arms were raised; there was nothing to stop the blade from slipping into his soft flesh. She heard the man grunt, felt the spear stick into him, just as a knife came down on her left arm.

Tersh cried out in pain, losing her grip on her spear and stumbling back. Someone grabbed the sword from the fallen man, who crumpled to the street, blood gurgling out of his mouth as he moaned in pain. Tersh stumbled back, four armed men coming at her, with no way to defend herself against them all.

I speak for the Goddess of Death, she thought to herself. I cannot die here.

The man closest to her, whose knife was a hand’s length from plunging into her chest, suddenly called out in agony, falling to his knees. Tersh first saw the bronze spear in his side, then the man who held it. All attention turned to this stranger. The three still standing turned to the newcomer, now aiming their attacks at him.

The stranger pulled the spear out, chucking it swiftly towards the man farthest from him. Before the spear hit he was already pulling a sword from the belt at his side. He slashed at one man’s belly, and as he folded over, clutching at his guts to keep them from spilling onto the street, he stabbed the next man in the throat – just as the spear hit the man, easily sliding into his ribs, and throwing him onto his back.

Everything went still. Some of the men on the ground were still groaning in pain, but it was clear from their injuries they would be dead soon. The man with the sword in his neck stood a moment longer, his eyes open wide in shock. His arm came up to grab the blade but went limp before he could reach it. He collapsed onto the street next to his fellow cutthroats.

Tersh scrambled to grab her spear, jerking it out of the now dead man. She swivelled around to aim at this newcomer, but the man was paying no attention to Tersh. He was wiping his bloody sword on one of the dead men’s clothes, before putting it back into his belt.

He muttered something, then spat on their bodies, before walking over to retrieve his own spear.

Tersh felt her body relax, and became aware of how fast her heart was beating, and how heavily she was breathing. “Who… who are you,” she asked in the tongue of Mahat, hoping the man could understand.

The stranger regarded Tersh a moment, and the Whisperer got a good look at him. His hair was a lighter colour than most of his people had, perhaps brightened by the sun, and she thought he had sandy eyes, it was hard to tell. From the few grey hairs speckling his beard Tersh guessed he had seen around three full cycles.

“Are you a soldier?” Tersh asked, but the man wore no insignia or helmet.

He laughed softly. “… I was a soldier.” He answered slowly, perhaps not sure if he could trust the Whisperer.

“I am called…” her voice seemed weak. She stood to her full height – which was still shorter than this man – and cleared her throat. “I am called Tersh Hal’Reekrah of the tribe Go’angrin.”

“Well, Tersh Hal’Reekrah. My name is Tuthalya, and I suggest you go home to your tribe. These streets are no place for a Whisperer of the Dead.”

“Of the Gods,” Tersh was quick to correct him.

Tuthalya grinned. “I’m sure…” he turned to walk away.

“What of these men?” Tersh looked around, all five were dead now, Arzaia still nowhere to be seen.

“They’re another man’s mess to clean. You best leave before they’re found though. People here won’t take kindly to a Rattlecloak having killed them, even if they were scum.”

Tersh looked at the first man who had fallen. The man she had killed with barely a second thought. Shouldn’t she feel more… something? Shouldn’t she just feel more? She felt nothing for the dead man, except perhaps relief that she wasn’t the one lying on the street in a pool of blood.

“I’ve… never killed a man before,” then Tersh looked up at Tuthalya in surprise. “How did you know I was a Whisperer?”

The man chuckled. “Everyone knows who you are. Even if they didn’t see you with your cloak. Your hair and face, you’re a ruby in a sea of diamonds. Everyone knows there’s a Whisperer walking among them. You don’t look like anyone from Mahat; you certainly don’t look like one from Ethia. So you must be the Whisperer everyone is talking about. Why do you think I saved your life?”

“You fear my blood on your streets?”

“This city was built of the bones of your people, its walls were mortared with your blood, and it has been cursed ever since. This land needs no more curses. You’re right, I was a soldier once, but this land only takes,” his laugh turned into a sigh. “There’s nothing here for me. I’m leaving, going back to my family’s home in the mountains.”

“Nesate?” Tersh turned in the direction the mountains must have been, though they were hidden in darkness.

“No, far closer. After the winter, when the pass has cleared, I will leave here. Until then, I need no more curses. So, I say again, go home. Leave us be.”

“Is there an inn that will take me?”

Tuthalya laughed. “No. There is no inn. There is no one.”

The ex-soldier continued to walk, and Tersh let him go. She turned and left as well, going back the way she had come. No, there was no inn and no one to care for her. There was still one place for her though. The gate soon loomed in front of her again. There was only one place for a Whisperer in this city.