Chapter 4

BEHIND THE SCENES OF THE STAR GATE PROGRAM:

Edwin C. May’s Story

A

uthors’ Note: With three authors and content in a book that could easily be a first person narrative at times, it’s always difficult to decide whether to jump from a personal narration to more of a third person reporting. To make it easier on our readers, we opted for the third–but we do underscore that this story is Ed May’s experience.

In late 1975, Edwin C. May joined an on-going, highly classified program at what was then Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International) as a consultant. The program and its personnel were to study extrasensory perception under the label “remote viewing” and its application for gathering information for the US military and intelligence communities. Up until that point, by academic training, degree and for a career, May was a nuclear physicist. The program director, Dr. Harold (Hal) Puthoff, called May into his office, pulled material out of an imposing safe, and showed it to May. He received his SECRET government clearance and his career took a major turn.

“What he showed me blew my mind,” said May. “Even to this day, thirty six years later, I still get goose bumps thinking about the then classified examples he showed me.” From that point forward, May has made ESP research his profession, applying it to problems involving the US national interest. Most of his friends to this day remain dumbfounded that he managed to make this seemingly illogical transition. In this chapter, we learn the story of Ed May’s life-changing career shift from academic physics research to directing the US Government’s secret ESP spying program, now known as Star Gate, and his part in both the operations (the

remote viewing “missions”) and the military/government bureaucratic process to keep it going.

What Puthoff showed him has been declassified, but at the time, this required government clearances to view. To give some idea of what was in the material, the following is a report of a remote viewing session from Puthoff and Russell Targ’s final report to the CIA, dated December 1, 1975. Note that the viewer, S1, was later identified as retired police commissioner Pat Price.

Date: 1 June 1973, 1700 hours, Menlo Park, California.

Protocol: Coordinates 38°23'45"to 48"N, 79°25'00"W were given (with no further description) by experimenter Dr. H.E. Puthoff to subject Sl by telephone to initiate experiment.

On the morning of 4 June 1973, Sl’s written response (dated 2 June 1973, 1250 to 1350 hours, Lake Tahoe, California) was received in the mail:

Looked at general area from altitude of about 1500 ft. above highest terrain. On my left forward quadrant is a peak in a chain of mountains, elevation approximately 4996 ft. above sea level. Slopes are grayish slate covered with variety of broadleaf trees, vines, shrubbery, and undergrowth. I am facing about 3° to 5° west of north. Looking down the mountain to the right (east) side is a roadway—freeway, country style—curves then heads ENE to a fairly large city about 30 to 40 miles distant. This area was a battleground in the Civil War—low rolling hills, creeks, few lakes or reservoirs. There is a smaller town a little SE about 15 to 20 miles distant with small settlements, village type, very rural, scattered around. Looking across the peak, 2500 to 3000 ft. mountains stretch out for a hundred or so miles. Area is essentially wooded. Some of the westerly slopes are eroded and gully washed—looks like strip-mining, coal mainly.

Weather at this time is cloudy, rainy. Temperature at my altitude about 54°F—high cumulo nimbus clouds to about 25,000 to 30,000 ft. Clear area, but turbulent, between that level and some cirro stratus at 46,000 ft. Air mass in that strip moving WNW to SE.

1318 hours—Perceived that peak area has large underground storage areas. Road comes up back side of mountains (west slopes), fairly well concealed, looks deliberately so. It’s cut under trees where possible—would be very hard to detect flying over area. Looks like former missile site—bases for launchers still there, but area now houses record storage area, microfilm, file cabinets; as you go into underground area through aluminum rolled up doors, first areas filled with records, etc. Rooms about 100-ft long, 40-ft wide, 20-ft ceilings, with concrete supporting pilasters, flare-shaped. Temperature cool—fluorescent lighted. Personnel, Army 5th

Corps Engineers. M/Sgt.

Long on desk placard on grey steel desk—file cabinets security locked—combination locks, steel rods through eyebolts. Beyond these rooms, heading east, are several bays with computers, communication equipment, large maps, display type, overlays. Personnel, Army Signal Corps. Elevators.

1330 hours—Looked over general area from original location again—valleys quite hazy, lightning about 30 miles north along mountain ridge. Temperature drop about 6°F, it’s about 48°F. Looking for other significances: see warm air mass moving in from SW colliding with cool air mass about 100 miles ESE from my viewpoint. Air is very turbulent—tornado type; birds in my area seeking heavy cover. There is a fairly large river that I can see about 15 to 20 miles north and slightly west; runs NE then curves in wide valley running SW to NE; river then runs SE. Area to east: low rolling hills. Quite a few Civil War monuments. A marble colonnade type: ‘In this area was fought the battle of Lynchburg where many brave men of the Union and Confederate Army’s (sic) fell. We dedicate this area to all peace loving people of the future—Daughters G.A.R.’

On a later date Sl was asked to return to the West Virginia site with the goal of obtaining information on code words, if possible. In response, Sl supplied the following information:

Top of desk had papers labeled “Flytrap” and “Minerva”. File cabinet on north wall labeled “Operation Pool” … (third word unreadable).

Folders inside cabinet labeled “Cueball”, “14 Ball”, “Ball”, “8 Ball”, and “Rackup”. Name of site vaguely seems like Hayfork or Haystack. Personnel: Col. R.J. Hamilton, Maj. Gen. George R. Nash, Major John C. Calhoun (??).

Urals Site (S1)

After obtaining a reading on the West Virginia site, Sl volunteered that he had scanned the other side of the globe for a Communist Bloc equivalent and found one located in the Urals at 65°00'57"N, 59°59'59"E, described as follows:

Elevation, 6200 ft. Scrubby brush, tundra-type ground hummocks, rocky outcroppings, mountains with fairly steep slopes. Facing north, about 60 miles ground slopes to marshland. Mountain chain runs off to right about 35° east of north. Facing south, mountains run fairly north and south. Facing west, mountains drop down to foothills for 60 miles or so; some rivers running roughly north. Facing east, mountains are rather abrupt, dropping to rolling hills and to flat land. Area site underground, reinforced concrete, doorways of steel of the roll-up type. Unusually high ratio of women to men, at least at night. I

see some helipads, concrete. Light rail tracks run from pads to another set of rails that parallel the doors into the mountain.

Thirty miles north (5° west of north) of the site is a radar installation with one large (165 ft.) dish and two small fast-track dishes.

The two reports for the West Virginia Site, and the report for the Urals Site were verified by personnel in the sponsor organization as being substantially correct. The results of the evaluation are contained in a separate report filed with the COTR [Contracting Office Technical Representative].

As it turns out, the West Virginia site was a very secret National Security Agency (NSA) listening post, and Pat’s data spawned a substantial internal security investigation that showed no wrongdoing on the part of the SRI team or Pat. All this happened before the internet and tools like Google Earth. In essence, it was data like this from Pat and others during those early days of the project that cemented the US Government’s commitment to the remote viewing programs for the next twenty years.

While the above engendered much curiosity on the part of Ed May, others would (and do) look at such reports with great skepticism and even downright disbelief. How did May even get to that point, and why did that push him in the new and different life direction? “Unlike many of my colleagues, I never had any experience with matters psychic,” said May. “I did not awake one night to find my deceased grandmother at the foot of my bed, nor had I experienced or even heard of an out-of-body experience.” So what happened to bring a nuclear physicist so far into the ESP Wars? To get to the answer to that question, first a bit of background on Dr. Edwin C. May.

☐☐

Born in Boston just before the US entered World War II, his father was a Navy man, and as with many military families, he moved to various posts in the US until his father finally saw action in the Pacific theater. After the war, the family settled on a ranch near Tucson, Arizona. Even in his early years, he was fascinated with all things Russian, arguably setting some of his future path. Studying the World Book Encyclopedia, he taught himself the Cyrillic alphabet and learned some of the geography of Russia. “When Sputnik began orbiting the Earth, I could not wait to run outside to watch this ‘star’ glide silently overhead—for me, this was quite a thrill.”

His high school education at a boarding school in Tucson was instrumental in shaping his career. In his senior year (1958), he took physics from a teacher who added beginning calculus as part of the course, which for the time was most unusual. This stimulated his interest in the subject, and he did quite well at it

.

His mother, who had spent much of her life before he was born in Boston, wanted him to apply to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge. “I told her it was merely an engineering school; that I had a higher calling, being destined for physics.” Ultimately, he ended up at the University of Rochester, NY, anxious to start his new life as a physics major. He applied for the advanced physics course and was accepted.

While he did not do well in most of his other subjects in college, physics was his one real success. He excelled in the physics laboratory, especially in nuclear instrumentation, high-speed electronics, and gamma ray angular correlation measurements—advanced fields for a college senior at that time. “Fortunately, my physics professors wrote glowing graduate school recommendations that offset my otherwise mediocre grades.”

As with so many other American college students, he spent his summers working. Beginning in 1960 and continuing for the next five summers, he worked at the Rand Corporation, located right on the beach in Santa Monica, CA. Rand, while a private company, was mostly a “think tank” for the US Air Force. “As a child I had learned basic piloting skills as a member of the Civil Air Patrol cadet program, so working for the Air Force, even indirectly, was a particular thrill. This was also my introduction to the world of state secrets in that security clearances were required even for summer employees.” While his work was mostly in atmospheric physics, he did analyze some intelligence, mostly in the nuclear domain. Thus began a lifelong career on the edges of the intelligence community as a contributing analyst.

In 1962, after graduating from the University of Rochester, he began his doctoral studies at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh (now known as Carnegie-Mellon University). His first day there set another precedent for his life, as May describes:

“While wandering lost through one of the faculty buildings, I saw an Asian Indian hunched over an apparatus that I immediately recognized from my work at Rochester.

Curious, I went in and asked, ‘Isn’t that a gamma-gamma angular correlation setup?’

“The Indian said, ‘Yes, and who are you?’

“We struck up a conversation, and it turned out he was Professor S. Jha, one of the best-known and respected researchers in nuclear structure and Mösbauer studies. Within weeks I began working for Jha in his laboratory.”

Unfortunately, Professor Jha and his laboratory were May’s only real contact with academia. Still young (22), he spent most of his time outside the lab in non-academic pursuits like so many other college and graduate students time enjoying extended lunches, learning to play a bagpipe (perhaps not so common!), and partying in general. Physics as an academic pursuit had not yet become his main agenda

.

May’s lifestyle choices caught up with him in early 1964 when the physics department asked him to leave. The timing was bad, as this revelation was followed immediately by a “friendly” request by the US Army to appear for a draft induction physical exam. US involvement in the Vietnam War had just begun.

“Believe me, there is no more effective wake-up call for a young man than the threat of being drafted. I told Professor Jha my tale of woe and fortunately, he responded with a wonderful solution. One of his research contracts was with the US Navy and he was able to hire me as a laboratory technician under that project. By a stroke of luck, as an employee in the defense industry, I could avoid going to war in Vietnam.”

May worked for Jha until late in 1964. Then one day, he was led down the street to the University of Pittsburgh, into the office of Professor Bernard L. Cohen, one of the top experimentalists in nuclear structure and reaction mechanisms.

As May recalls, Jha said, “Bernie, this fellow has had some academic difficulty in my department, but he is simply one of the best experimentalists I have ever watched at work in a lab. You should have him in your department and he should work for you.”

The recommendation took, and Edwin May began his second graduate school career. “With fire in my belly, I was able to work with a mature and focused intensity.”

He joined the University of Pittsburgh as a Ph.D. candidate and began working in the accelerator laboratory under Professor Cohen. Jha’s faith in him proved to be well-founded, as he did well in academics, learned a great deal about experimental methodologies and hardware, and wrote a Ph.D. dissertation entitled, “Nuclear Reaction Studies via the (p,pn) Reaction on Light Nuclei and the (d,pn) Reaction on Medium to Heavy Nuclei.”

During his studies at the University of Pittsburgh, May met another Indian who would become a trusted friend and indirectly provide another career influence: S. Gangadharan, or “Gangs” for short. Although he was getting his Ph.D. in nuclear chemistry, their experimental work was quite similar, so they helped each other. That was the beginning of a 40-year friendship that ended suddenly in 2000 with the unexpected passing of Gangs. In the interim, he introduced May to his family, and Gangs became the main link to the large network of close friends and associates in India that he retains to this day.

The late Dr. S. Gangadharan (Gangs)—Director, Board of Radiation and Isotope Technology, Bhabha Atomic Research Center, India

May received his Ph.D. in 1968 and headed for his first post-doctoral assignment in the physics department and cyclotron laboratory at the University of California at Davis.

During his post-doctoral appointment at UC Davis, May had his first real exposure to the world of psi. He attended a conference that was organized by Professor Charles Tart, a well-known and respected psychologist who at that time was mostly interested in altered states of consciousness. One of the speakers was a very businesslike person named Robert Monroe who talked about something he had never heard of before: out-of-body experiences. These were new and fascinating ideas to May, and he wasted no time in buying Monroe’s book, Journeys Out of the Body.

“If this down-to-earth fellow could get out of his body, surely I could do it more easily, being an inquiring scientist and all,” said May. “That arrogance turned out to be totally unjustified. I tried for many months to get out of my body with no luck at all, and set the whole thing aside as foolishness.”

At the end of his post-doctoral appointment, he moved to San Francisco to explore his newfound freedom. During part of the year, he taught physics in the so-called Free University of San Francisco and immersed himself in activities typical of California in the 1970s. These included attending a lecture on serious parapsychology research by Charles Honorton, who became a leader in parapsychological research. “The way he explained the subject piqued my interest as it sounded to me like ‘real’ science, with testable hypotheses and solid statistical analyses.” May had dinner with Honorton, and was offered sound answers to all his

questions. “But I remained unconvinced that any of these interesting ideas were true.”

After a bit of library research, he discovered that, in India, many of the concepts he had been learning about were generally accepted as fact. He was drawn to India, where he had visited his old friend Gangadharan (Gangs) in 1970 (and fell in love with the country). By then, Gangs was actively pursuing his career at the Bhabha Atomic Research Center in Mumbai. He wrote to his friend and described his newfound interest in psychic phenomena. “I explained that if even a small fraction of what I heard about parapsychology were true, then the implications for physics were boundless. So I proposed that I come to India and focus our effort on psychic phenomena for a year of collaborative research.”

In order to get there, in 1973, May and Gangadharan shared a scheme. At that time, the US Congress had passed Public Law 480, which allowed India to pay its financial debt to the US in its national, soft currency, the Rupee. As a result, the US had approximately one billion US dollars’ worth of Indian Rupees that, by law, could not be exchanged anywhere into international hard currency. Thus, academics could benefit by submitting research proposals on any topic whatsoever, and if the cover page indicated that the funds for the research were to come from Public Law 480, the proposals often were not even sent out for peer review! The US was anxious to use these Indian Rupees. While researchers could spend nearly unlimited amounts of money in India, they could not, for example, purchase an international flight, because that had to be done in hard currency. They had to come up with their own funds for that.

Their scheme involved a neutron-activation device developed at the University of California at Berkeley that allowed archaeologists to determine if some ancient clay pottery shard was made from local clay—that is, from the soil near where the shard was found—or if it came from some other, perhaps distant place. In this way, archaeologists could map the trading routes of peoples of the ancient world.

They wanted to use Public Law 480 funds to do just that with the substantial number of clay pots lying in museums all over India. “If truth be told, it was an excuse to use government funds to pay for travel all over India–and also to explore some important science.”

May had decided to look into the yogis in India rather than the clay pots, and thought that could be a hard sell. However, much to his surprise he received an enthusiastic response from Gangs explaining that he had always been interested in the paranormal. May began doing his homework for the trip by reading much of the English-language literature of those who had gone before in parapsychology. As part of his preparations, he built an elaborate random number generator device (long before personal computers) and gathered other gear to measure psychokinesis, the purported capacity of mind over matter

.

“As an arrogant young scientist, I of course assumed that I could easily surpass the work of my predecessors, armed with my extensive Indian connections.” Thus, off he went in August 1974 to live with Gangs, his wife Mahalakshmi, and their new son Ramprasad at Anushakti Nagar (“atomic energy city”), expecting to make Nobel Prize-winning discoveries of mind over matter.

However, after nearly a year of fascinating experiences in South India, May had to admit that he had not in fact witnessed any truly paranormal phenomena. “Looking back on that year, I feel ashamed of my own arrogance, cultural ignorance, and general naiveté. I now know that what I had undertaken should not be the job of Westerners, no matter how kindly they regard the culture. The challenge is to examine critically a culturally embedded concept such as ‘psi’ phenomena. Being outsiders, we cannot comprehend the faith and emotional structures that support the beliefs. Objectivity is impossible, since we risk being overly critical one moment and emotionally captivated the next, either of these consequences being detrimental to a scientific inquiry. Additionally, my outsider status profoundly affected the way people interacted with me, distorting my impressions further.”

While scientific research on siddhis—the Sanskrit term for psi abilities—is a possibility, it is difficult to separate superstition, magic tricks and outright fraud in the search for true psi experiences. Fighting to eradicate superstition is a task that the rationalists in Indian society, as in any other culture, are faced with. Some of May’s experiences during this time can be found in an article he wrote on the topic for Psychic magazine.1

As his stay in India was approaching its end, he wrote a ten-page letter to Charles Honorton suggesting a number of ways in which they could collaborate at the laboratory at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, NY, where Honorton was working. In response to May’s request, he received a one-word answer: “Yes!”

An Introduction to Serious ESP Research

Maimonides had been the site of extensive parapsychological research with dream telepathy by Drs. Montague Ullman and Stanley Krippner, and had expanded their parapsychological research to include a number of other areas and researchers. “From the spring of 1975 to the following winter, my ESP research went into high gear,” said May, “as I studied serious parapsychology research with a master [Honorton] and saw substantial evidence for the existence of ESP. I was hooked.”

During his time working with Honorton, he met an artist and psychic, Ingo Swann, who was involved in psychokinesis experiments at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) near San Francisco. Swann was curious about May’s technical and experimental background, and they became friends. Over several months, they conducted a few pilot studies together, with Swann as a psychic participant at Maimonides.

Charles Honorton: Maimonides (1975)

In the end, Ingo encouraged Dr. Harold Puthoff, the SRI program’s director, to hire Ed to help with the on-going psychokinesis experiments. Thus, it was Ingo Swan who really got May started on his twenty-year career investigating and utilizing psychic phenomena, something for which he said he “will be eternally grateful.”

However, unknown to May at the time, some elements of the research program at SRI were classified as Top Secret, and were being funded by the CIA.

Except for rare earlier instances, the US government became seriously interested in using ESP for military and intelligence applications only after 1972. Since then, a number of authors, including remote viewer Joseph McMoneagle, have written about the participation of the government in its 20-year, 20-million-dollar program that came to be known as Star Gate. The early history of this program has been described by Puthoff and Targ in their 1976 book, Mind Reach. However, many aspects of the project were under strict secrecy guidelines or considered classified information, and thus were not mentioned at all in that book. As of this writing, however, most of the project data and methods are either in the public domain or have been otherwise declassified, which is why we can tell the true story of what happened there.

May joined the SRI team first in 1975 as a consultant and became a full-time employee as a senior research physicist the following year. Once his “Secret” clearance was in effect, he learned what was really going on inside the walls of the Star Gate program. The quality of the data astounded May, and it frustrated him how few people on the outside understood the truth about extrasensory perception

.

In 1982, Russell Targ left the program and in 1985, Harold Puthoff stepped out of the program as well. Thus, the directorship of the Star Gate program was passed to Edwin C. May.

The ESP Program on May’s Watch

From the inception of the project under the CIA’s auspices in 1972 through 1979, the SRI program had three primary responsibilities. First, to use ESP to obtain information about potential threats from the Soviet Union, other Eastern Bloc countries, and the People’s Republic of China. Second, to assess the credibility and accuracy of intelligence regarding ESP research that was slowly filtering out from the Soviet Union. Finally, though with minimal support, to conduct basic and applied research. Basic research concerned the fundamental physics, physiology, and psychology of ESP, whereas applied research sought ways to make the end-product information more accurate and reliable.

It is a sad fact that modern military decision makers are extremely hesitant to finance programs based on a putative extrasensory capability. During the Cold War, Senator William Proxmire invented a prize—the Golden Fleece Award—as a way of embarrassing government officials who routinely funded all sorts of silly projects. Thanks to academic prejudice and often ridiculous portrayals of psychic phenomena in the media, the study of ESP possessed a high “giggle” factor, regardless of the quality of the work. Both this giggle factor and the Fleece Award had a chilling effect in the funding community for ESP research. As a result, when May became the project director at SRI, more than forty percent of his time was spent attempting to raise funds so that the program could continue.

There were many successful applications of ESP within the project at SRI, and later at Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC). We’ll address some of those successes in a later chapter, but one example is an intelligence-like success that was never formally part of the Star Gate program, having occurred later. It resulted from a desperate call from one of May’s friends. While a leap ahead in time for Ed May’s story, it demonstrates how useful the process of remote viewing can be, and how the process works for certain tasks.

On one of his many visits to Washington and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA)—the agency that gave SAIC a contract for research into ESP and its application—he met with Angela Ford. Angela was one of the DIA’s most skillful remote viewers, and she introduced May to “Esther,” who had been one of the managers of Bill Clinton’s first-term primary campaign in 1993. Once elected, Clinton appointed Esther to a high position in one of the departments in the Executive Branch of the government. Here is Angela’s photo.

Accomplished remote viewer: Angela D. Ford

May and Angela met “Esther” in her office, and he was impressed with her obvious and extensive connections to the Clinton family. On the wall or mounted elsewhere were a large number of photos, some of them signed, of Bill and “Esther” in various situations. There she was jogging with the President, playing with Socks, the family cat, chatting with Hillary, engaging in formal meetings, and so on—quite impressive, indeed.

“‘Esther’ and I went for dinner and enjoyed many in-depth discussions about the nature of reality, parapsychological phenomena of all kinds, and the politics of the day. Many meetings and dinners followed, and ‘Esther’ and I still maintain our friendship.”

Sometime during Clinton’s second term, May received a panicked telephone call from “Esther.” It seems that her 20-something daughter had failed to show up at work and was missing.

“’Esther,’ why the hell are you calling me?” May asked. “Given your position in the West Wing, you can have direct access to the FBI, the Secret Service, and local law enforcement. Why me?”

Understandably, she was in a bit of a panic, but she told him that the best efforts from government officials had been of no help. She urged him to ask some of the remote viewers to see whether they could help somehow. In the laboratory, this is called a “search task.” Although searching for lost things, such as people, aircraft,

weapons, or drugs seems an obvious thing to do with psychics, this generally turns out to be a very challenging task.

The Search Task

Three basic approaches have worked for a search task in the field and in the laboratory. The first is to ask psychics to “stick a pin in a map” corresponding to the lost person. In May’s experience, this approach usually doesn’t work. When it does work, people often give this positive result undeserved attention.

A more effective technique is the standard remote viewing of a target such as the whereabouts of a missing person, in this case “Esther’s” daughter. However, even this approach has its problems and an excellent remote viewing might not contribute much to actually finding the lost person.

Imagine the following scenario: We wish to find a Soviet submarine that is lurking underwater somewhere off the California coast. Fortunately, we have at our disposal a psychic viewer who is nearly perfect with her impressions. The viewer describes the interior of the sub exactly, describes the crewmembers in detail, provides the name of the Captain and his children, and tells what the crew ate for dinner that evening. We now have top-of-the-line accurate psychic data, but it in no way helps us to find the sub.

The viewer then takes a psychic “look outside” of the sub, which yields an amazingly accurate description of—you guessed it—water!

This is one example of how the intelligence value, in this case what is needed to find Esther’s daughter, is often unrelated to the quality of the remote viewing. The quality of remote viewing can be excellent, but the value of the information worthless.

Fortunately, the real-world research provides a compromise. In the standard out-bound remote viewing protocol developed by Targ and Puthoff, an “agent” travels to some randomly chosen location and the viewer simply describes the surroundings where that person is currently located. This is the bread-and-butter laboratory remote viewing experiment.

How could this approach be used to locate a person?

That depends upon the accuracy and detail of the psychic response. In the ultimate case, suppose the viewer gives the street name and address of the hiding or lost person, then finding them is simply a job of going there and knocking at the appropriate door–assuming the person has not been moved, or assuming the task is to view where the person will be at a given point in the near future.

Dr. Nevin Lantz at SRI 1982

Back to “Esther’s” story and her missing daughter. May hesitantly agreed to ask three of the best viewers to try to describe the physical surroundings and emotional circumstances where she was currently located.

One of these was Nevin D. Lantz, Ph.D. who holds a degree in clinical psychology. Nevin had been formally associated with the project at SRI since the 1980s and was in charge of identifying personality factors that predict psychic ability by working with various consultants and conducting specific experiments. Additionally, he tasked Joe McMoneagle and Angela D. Ford—then still an excellent government remote viewer—with attempting to locate the missing young woman.

Nevin responded with a detailed psychological profile of the missing woman and with the good news that she was not in physical harm’s way, but had suffered a substantial psychological episode. Later they learned that this remote psychological assessment was accurate. A combination of the responses from Joe and Angela aided the FBI in recovering the missing woman. All’s well that ends well.

Another success with the search task happened earlier. Though it may sound impossible to some, this approach or something conceptually similar, has worked spectacularly well in the past. Consider the case of trying to find US Army Brigadier General Dozier who was kidnapped from his home in Verona, Italy on the evening of December 17, 1981.Joe McMoneagle was asked to locate the General by using remote viewing to accurately draw Dozier’s current location. Among the response data was a drawing of a unique circular park with a cathedral. As it turns out, by scouring maps and photographs for such a combination of structures, the searchers found one in the city of Padua, the place where General Dozier was rescued

.

Dozier was briefed the following February at the Command’s Special Compartmented Information Facility (SCIF—Bldg 4554) on the Grill Flame2

psychic program–this was the unclassified name for the then-classified SRI program. Dozier was then asked to review sketches and narratives generated during the Grill Flame sessions for any correlation to places or events surrounding his kidnapping. Dozier was so impressed with the data that he suggested that senior government officials, military officers, and leading business and political personalities be instructed in what to “think” if they were kidnapped so that psychic searchers could more easily locate them.

As a postscript to “Esther’s” story, since she was both relieved and especially happy at the outcome, May was convinced that the Star Gate project now enjoyed the attention of the West Wing of the White House and perhaps of the President, himself.

“So I sat back waiting for the flood of contract funds to appear in order to continue the research. Apparently, the only thing that happened was that a few of Joe’s books on the topic were handed to the President. No contract funds were forthcoming, and I take responsibility for that. It is simply not a good fundraising technique to do something noteworthy, and then wait for money to be thrown in one’s direction. Clearly one has to be much more proactive than that, whether in fundraising for a school project or for research at the cutting edge of science.”

The Mid 1980’s

In 1986, the program had a rather substantial 5-year Army contract of $10 million. As a result of these resources, significant progress was made in all of our primary tasks. For the first time, May and his colleagues actually had a charter to conduct basic research to attempt to understand the underlying mechanisms of parapsychological phenomena as part of their role as scientific support of the Army/DIA’s in-house remote viewing group. Until this contract, they were required mostly to conduct operations-oriented research–in other words, investigations designed to improve the quality of the results and not expected to understand the mechanisms. Additionally, they continued to conduct foreign assessments—analysis of potential parapsychological threats from other countries, and to a limited degree, remote viewing on foreign sites.

The funding was never fully realized, as it happens. In the third year, it was cut in two, and after the fourth year, all the money vanished. So of the total $10M, only half of it actually came through.

One aspect of the large Army contract was that they were required to conform to the wishes of three separate Army-constituted panels, unlike any previous review panels (of which there were many): a Scientific Oversight Committee, an Institutional Review Board (a.k.a. Human Use Review Committee), and a Pentagon

Policy Review Committee. All committee members were required to hold active security clearances. Let us emphasize that these committees were not “rubber-stamp” bodies. Rather, their members agreed to long-term commitments, and they all took their responsibilities very seriously. May commented, “As the recipient of their reviews, I can attest that the quality of our output improved substantially.”

Perhaps the least active but arguably the most important group was the Pentagon Policy Oversight Committee. It consisted of three members of note, some drawn from the Defense Policy Board, whose sole responsibility was to determine whether or not their activity met the goals and objectives of the Department of Defense. Over the course of four years, May was asked to meet with this group in the Pentagon perhaps three times. Their reports were supportive of the activities, and the program and personnel passed muster with regard to the overall mission.

The second oversight committee may surprise many. The US Department of Defense is actually very concerned about the ethical treatment of humans who participate in DOD-directed experiments. While the folks at SRI might easily have asked the in-place Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Stanford University, which is also known by other names such as Human Use Review Committee or Ethics Committee to review their work, they did not. Rather, they built their own IRB from scratch, because the DOD requirements are actually stricter than for IRBs governed by the Department of Health and Human Services. The mix of professions for such an IRB, which are prescribed by law, included a member of the clergy, a layperson, a lawyer, and physicians of various types. Believe it or not, their clergy-person was a Buddhist priest who held a Secret security clearance. Within their IRB was who’s who of the medical world, including one Nobel Laureate.

As with other IRBs, they were required to write up a detailed human-use protocol for each individual experiment in their contractual statement of work. This write-up had to explain why the experiment was being conducted. It had to cover the nature of its physical, financial, emotional, and health risks. It included the possible outcomes that were anticipated and what would be concluded accordingly. Finally, it had to cover the likelihood that each of these potential outcomes would meet the primary objective of the experiment. In other words, would all possible outcomes justify the use of human subjects?

All of the experimental participants were additionally required to undergo complete physical, psychological, and neuropsychological exams. If these revealed abnormalities of any kind, and May and his colleagues still wished that person to participate, they had to obtain a waiver from the person and his or her physician. This was a very time-consuming, but critically important task.

The final, and probably the most active panel was the Scientific Oversight Committee (SOC). For the first two years, there were twelve members that were drawn from lists of people supplied by the project personnel, and ones provided by the Army. The Army had the final decision regarding who would serve on the

committee. They all were paid under the contract for their time and travel. A threshold requirement for serving on the SOC was that the member be skeptical of the putative parapsychological phenomena, but at the same time, open-minded enough to want to take the job seriously. Furthermore, their time commitment was substantial— the job was to last for the five-year duration of the contract. However, because in the third year of the contract the $2M budget was cut in half, May reluctantly had to reduce the SOC membership down to only five.

The SOC had three primary tasks: to review and approve the detailed experimental protocol for every experiment to be conducted under the Army contract; to exercise unannounced drop-in privileges in order to see firsthand what was happening; and to review critically, in writing, the final reports for each of the tasks in the contractual statement of work. There were 38 reports in the first year alone.

Because the group was highly professional, the first of the SOC’s three tasks was rather straightforward. From time to time they did some protocol “tweaking,” but for the most part, the protocols they submitted were approved directly, with little or no substantive change.

The SOC’s second task—unannounced drop-in privileges—looked good on paper, but was hardly ever exercised. “I suppose this was to be expected, given that the Committee members were senior professionals with active individual careers,” said May.

The main SOC action came with their third responsibility—critical review of the program’s final reports. Once the reports were completed and had been copy-edited by SRI International (the new official name for Stanford Research Institute) professional editors, they were copied and sent to all the SOC members. The committee members were to review them as if they had been submitted to a scientific journal of which the member was editor-in-chief. They took notes and eventually provided their comments in writing directly to the Army’s Contract Offices’ Technical Representative (COTR). In this case, the representative was an Army officer with the rank of full Colonel who had been transferred to the Army Presidio in San Francisco, but whose full-time responsibility was to be in his office in our group at SRI. Their opinions were added to the final reports as an appendix.

In addition to their written opinions, the SRI program personnel hosted a two-day meeting each year during which they presented their results and discussed the outcomes with the SOC group in person. There was good news and bad— although the bad news should be construed as good. Because they were successful, they won 85% of the vigorous and sometimes loud arguments, but the better news was the 15% they lost. The program’s scientific “product” so to speak, sharply improved, and that improvement manifested in two ways.

According to May, “First, we learned to approach all positive results from our experiments in a skeptical way: assume what we just saw was a mistake and set

about finding it. If we failed to find an error, we could assume something interesting was happening. Secondly, because of the interdisciplinary nature of the SOC, our group was exposed to experimental and theoretical techniques that were outside of the training of our own researchers but could be incorporated with the SOC’s assistance. My interaction with the SOC is among the highlights of my professional, academic research career.”

However, there were frustrations. As an example to illustrate, one year they invited Professor Jessica Utts, a statistician, to work with them as a visiting scientist. During that year, with her assistance, the program improved upon the more traditional method of analyzing the results of remote viewing experiments by using more sophisticated statistical and mathematical approaches. One of the SOC members chaired the statistics department of one of the University of California’s major campuses. This individual rejected the new approach without offering any scientific argument, saying that it was too complex and that there was too much room for subtle, unknown errors. “We all have heard the expression that ESP stands for ‘Error Some Place,’ which was his assumption, but even so, that statistician’s response was quite unexpected.”

As it turned out, May had the opportunity to show a single example (then highly classified) of a simulated operational remote viewing conducted as a test by an Air Force client, the full details of which will be found in Chapter 6. The target was the special high-energy electron accelerator located at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, nearly 50 miles east of San Francisco. Naturally, the experiment team had no information with regard to the target or its location—called “double-blind” in the parlance of laboratory experiments, since both the subjects and the experimenters were “blind” to the target. The Air Force provided 100 percent “ground truth” —absolute confirmation of what the actual target looked like—so that they could conduct the analysis using the statistical methods that had been developed, though those methods had been so easily rejected by this one SOC member just mentioned. “The visual correspondences were stunning!” according to May.

After the presentation, the same SOC member came up to May and excitedly proclaimed that he “got it!” Of course, May thought he meant the statistical approach, but this was a wrong assumption. This single, visually stunning example convinced him that remote viewing was real. Later, May took him aside in the parking lot and read him the riot act! “How dare you! Jessica and our team have worked a year dotting our I’s and crossing our T’s to assure the best possible statistical analysis, yet you summarily rejected that approach as being evidential! On the other hand you become convinced about remote viewing from a single example that I cannot defend statistically or scientifically.” He was speechless.

It seems that May, and for that matter most of us, assume that science progresses on the basis of good scientific arguments and evidence, but we tend to leave out the emotional component. Robert Burton in a recent book, On Being Certain (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2009) points out that modern neuroscience suggests that it is the

emotional centers of the brain that become active as we become certain of our opinions and just about anything.

This is surprising to May, as “I had thought that scientists prefer to think that it is the logic and analysis portion of the brain that makes us certain. Maybe I experienced this with our statistician SOC member.”

How Well Did ESP Intelligence Collection Work at SRI?

There was another approach to gathering intelligence besides direct ESP in which the US Government took an interest. Normally, when a new military policy, weapons system, or battle order is being considered, the proposed new system is evaluated critically. Often two teams of evaluators, designated as Red and Blue, are assembled to criticize or support the plan, respectively. The SRI group was awarded a contract to participate in a Red team to evaluate a proposal by the Carter Administration, and later by the Reagan Administration, to deploy the new MX missile system.

The proposals were variations on the theme of building many more missile launching facilities than there are missiles, then continually moving the missiles covertly among the various launching facilities—let’s call it a nuclear shell game. The Congressional Budget Office originally estimated that procuring 200 MX missiles, building 5,800 shelters for them, and operating such a system would cost $28.3 billion dollars all the way through to the fiscal year 2000, while 300 MX missiles scattered about among 8,500 shelters would cost $37.6 billion dollars. The first option provided for one MX missile for every 29 shelters, while the second planned one missile for every 28 shelters. These were somewhat lower ratios than the one proposed by the Department of Defense, which suggested that there should be one missile for every 20 to 25 shelters.

Eventually, a “racetrack” idea gained favor. Each missile would be moved among the shelters located on spur roads radiating from a central, circular track. There would be about five such patterns, or clusters, in each of about 40 valleys in the deserts of Nevada and Utah. This racetrack system would allow transporters to shift missiles between shelters within 30 minutes, in time to escape incoming Soviet missiles after they have been launched. The racetracks would be about 56 kilometers in diameter.

The complexity and financial support that would have been required for this proposed system demonstrates how seriously the Carter Administration considered the concept. In fact, they were planning to move ahead as soon as possible. The US Air Force expected to begin site selection for the MX operation base test and training facility by 1980. Work on the first racetrack and shelters would begin by 1983, and the first ten MX missiles and 230 shelters were scheduled to be operational by 1986. The Soviets would not know where to aim their missiles in order to cause the most

damage to the US’s ability to retaliate, since our missiles would be moved continuously among the various shelters.

The question was whether or not this concept could be compromised using ESP. If so, we (the US) would have to assume that the Soviets could also accomplish this. Meaning, it would make no sense to build this vast system of racetracks and shelters in the first place.

The group’s proposal, which was eventually approved, included the following elements in the statement of work. The following is what they were going to do with the money if the contract was awarded to SRI:

Assuming a 1-in-20 ratio of missiles-to-shelter mix, determine the statistics of MX system compromise as a function of beyond chance hitting by ESP practitioners. [In other words, what were the results necessary to statistically show “hits” by the viewers were better than chance.]

Conduct a screening program involving about 100 SRI employees and other experienced ESP practitioners, utilizing a 1-in-20 screening device with 100 trials for each participant.

Take the five best people from the screening and have each of them contribute 200 more trials.

From these data, estimate the potential vulnerability of the racetrack, or shell game concept.

In addition, they used a sophisticated statistical technique coupled with a form of ESP called “dowsing” to see if they could compromise the system.

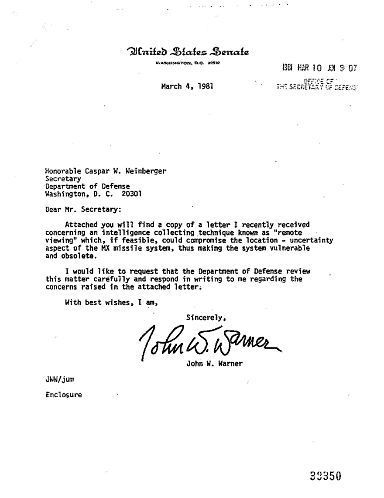

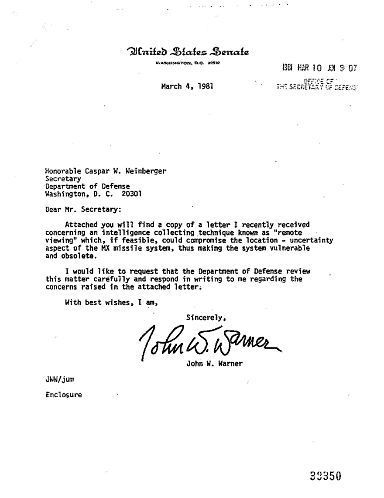

In their final report to the Government, they showed that ESP practitioners were able to locate the hypothetical missile in twelve out of twelve trials, with a total of 452 circle selections. The correct hit rate was over two-and-one-half times what was expected in a one-in-ten game. The figure below shows a letter on US Senate stationery from Senator John W. Warner (R-Virginia) to the Secretary of Defense at the time, the Honorable Caspar W. Weinberger, describing the contribution to the MX missile program.

May doubts that the data they gathered as the sole reason that kept the system from being built, but on the other hand, the ESP research reports surely contributed in an important way toward that end.

Beginning in 1986, the Air Force became exceptionally interested in learning the degree to which remote viewing could provide useful information on directed-energy weapon systems. To test this idea, they awarded a contract to examine this question in three trials: one per year, for three years. As always, they used a double-blind protocol, meaning that no one who interacted with the remote viewers knew anything about the potential target or even, in this case, the identity of the client. A session would play out as follows: “We were usually given the Social Security number of an individual none of us had met. In addition, we were told that on a

specific date this person would be somewhere in continental United States.” The individual would be on-site with the actual targets, making the individual a beacon for the remote viewing. “As project director, I knew that the targets would be directed-energy systems of some kind, but beyond that I too did not know any specifics.” In essence, the Social Security number was all the viewer would have as the targeting mechanism.

Senator Warner’s letter to the Secretary of Defense

Beginning at a specified time, Dr. Nevin Lantz, the project’s psychologist and active researcher, would assign a task to the viewer at midnight and again once every

eight hours, including the next day’s midnight. That task was simple: describe the surroundings where the person to whom the Social Security number belonged was standing. So far, nothing particularly new or inventive was involved. The analysis of the result was a breakthrough not only for laboratory studies. If used properly, it could easily have been adapted to the real world of psychic spying.

Before any of the sessions with a client began, May worked with the sponsor to define three categories of things they wanted to know about the target. First and foremost was the target’s function: why it was being developed. The Air Force had five or six different aspects in this category alone in which they were interested. The second category was physical relationships: an instrument, for example, might be under the building that was next to a truck. There were around ten such aspects. Lastly, they specified a rather long list of objects, similar to those one would expect from a traditional remote viewing.

For each of the targets, the Air Force filled out a table for each element in all three categories that was specific to each target to be used later and rated each to the degree to which each element was germane to that target and its location. After the psychic session, an analyst, who was blind to the target and its list of items, filled out the same table, but with regard to the degree to which each item was present in the psychic’s response.

Armed with both tables, one for the intended target and one for the response, the computer could take over. Although mathematically complex—the process is known as “fuzzy set analysis”—three simple ideas emerged from the computation. The accuracy was defined as the percentage of the Air Force predefined target that was obtained by the psychic. The reliability was defined as the percentage of the psychic’s response that was correct. And finally, the figure of merit was defined as the product of accuracy and reliability.

The way to obtain a high figure of merit was for the psychic to describe as much of the intended target as possible, but in as simple and minimal way as possible so as not to include many incorrect aspects. To get a hint of what a random response could be like in the absence of any psychic ability, they had determined in the laboratory that using a rough rule of thumb about a third of any site can be described by about a third of any response. Perhaps this may seem high, but this rule of thumb arose from considerable analyses of data collected in the laboratory.

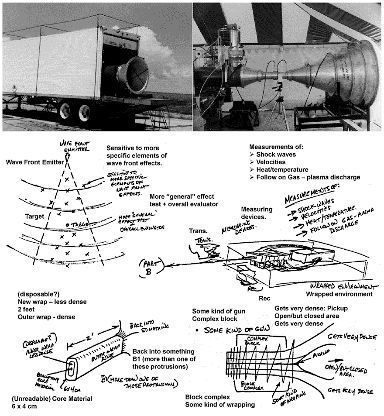

How did this work out? Here’s just one of three successful examples: Project Rose, a high frequency, high-power, microwave device in the New Mexico desert at Sandia National Laboratory.

Joe McMoneagle was the psychic on this trial. By the Air Force’s own assessment, the accuracy, reliability, and figure of merit for this case were 80 percent, 69 percent, and 55 percent, respectively. Keep in mind that chance or just Joe being lucky would predict these numbers to be 33 percent, 33 percent, and 11

percent, respectively. The figure on the following page shows that the drawing and pictures were more impressive.

“In my thirty years of experience in ESP research, I consider this case to be among the very best,” said May. “If this example had been an intelligence operation instead of a proof-of-principle session, an independent analyst would have no trouble whatsoever in identifying the target as a microwave device of some sort.” The drawings on the right in Figure 2 clearly show easily identifiable elements, such as a waveguide and microwave horn. Joe went on to say that, this device was in a wrapped environment and was being used as some kind of test evaluator.

Microwave target test bed for directed energy weapons systems. Ed May has added typed versions of some of the written words for clarity. These appear in small boxes.