Chapter 6

THE AMERICAN MILITARY ESP PROGRAM:

WHAT WORKED & WHAT DIDN’T

A

ny intelligence project such as Star Gate comes with pros and cons as far as running studies, applying science, assessing the validity and usefulness of the information, and deciding the overall efficacy of the project. There are bureaucratic and belief-centered issues that arise, especially with programs dealing with phenomena and processes that are themselves not understood, in this case the military and intelligence communities’ in-house efforts to research ESP.

Some question whether an in-house—meaning inside the US Government—program was necessary or even appropriate. Many question whether it actually worked. This is an easy question to ask, but the answer is quite complex. “I suppose if I had to do it all over again and it was up to me, I would not have established such a unit,” said Ed May. On the other hand, as we demonstrate in this chapter, there were some stunning successes, despite the crushing administrative, scientific, and personnel problems that emerged. Another indicator of its success in the broadest possible sense is that the in-house psychic spying unit lasted from 1978 until the whole program was closed down in 1995. It is all too easy to criticize the government and suggest that it lasted so long merely because of incompetence or because the project personnel had somehow pulled a con job on their superiors, but given the substantial number of powerful naysayers, its longevity can be considered quite a testimony to the unit’s overall value.

As mentioned earlier, prior to 1978, SRI had total responsibility for the psychic spying program. In those early days, there was very little funding support for any kind of research, but it was accomplished to some extent under the general heading of foreign assessment. Here’s an example.

Professor I. M. Kogan, a serious and accomplished information theorist in the Soviet Union, wrote an article entitled, “Is Telepathy Possible?” in 1971. The article was passed on to May and the project personnel by the Foreign Technology Division

of the Wright-Patterson Air Force base in Ohio. In that paper, Kogan suggested that the way ESP works is similar to a radio transmitter/receiver pairing. According to his hypothesis, while the sender in a telepathy experiment is thinking about the target, his or her brain gives off radio waves that are received by the brain of the psychic telepathic receiver. As it happens, the concept that telepathy works similar to radio is an old one in the West, possibly because the early concepts of ESP in the 19th

century evolved at the same time as other distance and invisible signal transmission—telegraphy and radio itself. Kogan’s paper deeply looked at this concept.

To test Kogan’s idea, the SRI folks piggybacked a then-classified extra task onto the Deep Quest project led by Stephan Schwartz of the Möbius Group in Los Angeles. Deep Quest was a psychic archeology project involving using remote viewing to find previously unknown sunken ships in the waters around Santa Catalina Island. Remote viewers Ingo Swann and Hella Hammid were part of the project. While Schwartz and his people were aware there was something additional going on, they were not privy to the actual study being done, though Swann and Hammid were. No mention of Ed May’s presence is included in any of the write-ups or television coverage of Deep Quest, and May is nowhere to be seen in the footage though he was actually present.

The added study was to consider whether or not radio waves could account for the information gathered via ESP. Given the undersea exploration that was part of Deep Quest, they were able to surround a psychic with a thick slab of seawater as a shield against brain-generated radio waves. As it turned out, the remote viewing test under such conditions showed that Kogan’s idea was not valid, due to the viewing being successful in spite of the shielding seawater.

As an aside, in 1992 Ed May had the honor of meeting Professor Kogan in person and after pleasantries, told him that there was bad news about Kogan’s seminal telepathy paper, that his radio theory of ESP was not correct. Kogan smiled and said he, too, had come to that same way of thinking and was glad to see the hypothesis had been properly tested. The photo below was taking in Moscow in 1996.

E

ven though the program at SRI was highly classified, word began to spread within the intelligence community that if they had an intractable problem that could not be solved using traditional methods of intelligence collection, they could, as an act of desperation, try those “far-out” psychics in California. Fortunately for the project and for the academic discipline of psychic research, the project’s success rate, while not great, was good enough to help solve a handful of these seemingly intractable problems. Or, as one CIA agent remarked on ABC-TV’s Nightline, these were three-martini moments!

L to R: I.M. Kogan, Edwin May, Joe McMoneagle

It became clear both to the project’s sponsors and to the folks working at SRI, that that they were facing a long-term problem. They simply could not rely on a small handful of psychics to continue to conduct intelligence collection via psychic means. There was a fairly obvious two-part solution to this problem: find people with some ESP talent then guide them in the development of their innate expertise.

This happens every day in sports. A recruitment scout sees a young person who, for example, is terrific at playing golf. Then that young person goes to golf camp, and if improvement is seen, she or he may acquire a golf pro to train with individually. Eventually, you might end up with someone like Tiger Woods. Why not follow the same path with remote viewers?

However, the solution creates two questions: how does one find the people with an innate skill, and then how does one train them to improve their psychic ability? These two problems, probably more than anything else, plagued the research team throughout the entire history of the US Government’s activity with ESP.

As described in Puthoff and Targ’s Mind Reach, substantial resources were expended in the early days at SRI to examine a handful of individuals from every possible perspective, in order to determine what makes these people special. In fact, research in parapsychology has looked at the same question, considering whether there were all sorts of common traits for people who did better at psychic tasks. Research has looked at all sorts of individual characteristics, from personality variables to family history, from altered states to belief factors (belief in psi, religious and cultural beliefs), covering both the psychology and physiology of the subjects. Correlations to a variety of factors have been found in parapsychology, but these weren’t necessarily important to remote viewing

.

So what did Targ and Puthoff find in their own consideration of the question? The short answer is … nothing! The ESP performers did have a tendency to possess IQs that were slightly higher than those of the population at large, but this was attributed to an artifact of the selection process, rather than something innate to ESP. During the entire 20-year program, this question was never answered effectively. The research reports, first at SRI and later at Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), are full of attempts to isolate some external factor that might correlate with an individual’s fundamental ESP skill. Over time, they did look at behavioral questions such as “does an individual physically do something different during a session when they are correct, compared to when they are not?” They also examined the viewers from neuropsychological and personality perspectives and even susceptibility to being hypnotized, but ultimately were unable to define a “psychic” type of individual.

Failing this, the best May and company could do was conclude that if you wanted to find psychics, you should ask large groups of people to try to function as psychics, and then select the ones that actually could.

At SRI, one of the formal government-directed tasks was to screen for psychic ability in a number of populations which included SRI employees across the Institute, a group from the United States Geological Survey, two different Stanford University alumni groups, and the San Francisco Bay Area MENSA society—an organization of individuals with exceptionally high IQs. Of approximately 600 people, only a small handful met a predefined criterion of being psychic according to strict laboratory conditions.

As to the other problem, bringing out the innate ESP that some people had, the Army wanted the project personnel to learn how to train the “average” soldier. During the early years at SRI, the project was funded by the CIA. After that, it was funded by the US Air Force, via the Foreign Technology Division of the Wright-Patterson Air Force base in Ohio. Two elements of the US Army became interested in the project a bit later. The first of these was the US Army Material Systems Analysis Activity, which was under the direction of John W. Kramar, attempted to establish a small remote viewing group at the Army’s Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland. This group never became formally established, but they conducted some traditional remote viewing trials against locations within a few kilometers of the post. “Having acted as an analyst for some of those trials,” said May, “I can attest that there was little evidence of psychic functioning.”

In parallel with all this work, Ingo Swann, that highly accomplished artist from New York City with substantial psychic ability who had befriended Ed May, was attempting to design a training system for remote viewing. Ingo was not a scientist, but he had a brilliant mind, and May can only praise his efforts. He worked 12 to 14 hours each day for years, much of this time being spent in the libraries at Stanford University

.

In the meantime, an Army group at the Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) became vitally interested in psychic research. Much of this story can be found in Joseph McMoneagle’s book, The Stargate Chronicles: Memoirs of a Psychic Spy. But the bottom line is that approximately 3,000 intelligence personnel worldwide were screened with regard to their potential participation as putative psychics in the Grill Flame activity.1

This screening involved their psychology, general interest in the topic, mental stability, and whether or not their records indicated a higher than normal success rate within their job categories. As described in the previous chapter, ultimately six individuals were selected to come to SRI for what was labeled “Technology Transfer.” That is, it was agreed to conduct six remote viewing sessions with each of the six army individuals, one of them being Joe McMoneagle.

This new project was highly sensitive, but it seemed to the folks at SRI that the Army was overly paranoid. Each person arriving at SRI for the six remote viewing sessions were signed in at the control desk using the name of Scotty Watt, the recently assigned commander of the group. That became an SRI joke, especially when the one female remote viewer signed in under that same name! In fact, the SRI people all considered the military intelligence experts to be gross amateurs. “Joe McMoneagle told me that the intelligence professionals at the working level in the Unit had also seen this as amateurish pseudo-security,” said May.

When the Army personnel flew out from the East to SRI for technology transfer, the original concern was that people on the West Coast might learn, and possibly leak, the names of those involved as psychics within the Ft. Meade unit. Most clandestine collection units go to extremes to protect the real names of those involved, especially in the collection—i.e., spying—side of a unit. Their military unit was supposed to be treated no differently. However, rather than regard these measures at all seriously, everyone treated them like a joke initially, because they involved “psychics” and not “real field agents.” That’s what was particularly annoying to the original six participants.

This group of six people proved to be quite psychic, under the strict laboratory conditions enforced at that time.

At about the same time, May landed a $495,000 contract with the US Army Missile Development Command located at the Redstone Army Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama. They worked with Randi Clinton, a senior official there who, incidentally, occupied the former office of Dr. Werner von Braun, the brilliant ex-Nazi rocket scientist. As May states, “My day-to-day contact there was with one of the most gifted scientists I had ever met in government service, Dr. Billy Jenkins. Our joint effort was to build from scratch a duplicate set of carefully designed hardware random number generators, similar to an electronic coin flipper, to see if previously published results could be replicated under exquisite engineering and laboratory controls.” SRI did its part with a successful replication, but the Army group never built their system. As part of this work, Jenkins was asked to provide a

briefing on the progress of the project as part of an overall assessment of the Grill Flame project.

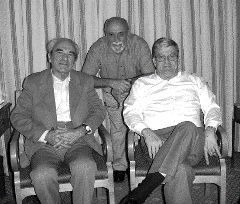

The proposed, but never shown Grill Flame cover slide

Since this was in the days before personal computers, Jenkins went to his Army graphic arts department and told them he needed a cover slide for his upcoming presentation that involved Project Grill Flame. He explained to them that it involved remote viewing, and told them a little about what that was. “Fortunately for all concerned, Jenkins showed me the cover slide before he gave his presentation,” said May, “so I was able to keep it from being shown!”

Does May think it was a good idea for the Army, or any other government organization for that matter, to set up their own operational unit to use psychics to collect intelligence information? “My answer would be ‘no’ if it were to be set up and run the way it previously had been done. Circumstances dictated what occurred back in 1978, but in retrospect, considering the requirements of science in concert with the performance of remote viewing, the seriousness with which it must be managed, and the structure within which it must operate—politically, socially, militarily, and otherwise—it was destined to turn out the way it did. That is, disastrously.”

Before we can start a discussion about success or failure, one must consider the meaning of these concepts in an intelligence environment and in light of the application of ESP.

In a very real sense, the Grill Flame / Star Gate project personnel were developing a new tool for the intelligence community. However, unlike an academic test where the parameters and analyses are easily set in advance, the intelligence value of any data, regardless of its origin, is often problematic. In general, intelligence gathering suffers from a major problem—the quality of the data is often separated from its intelligence value

.

Let us illustrate with a hypothetical situation: Suppose a spy satellite captures a high-resolution photograph of a new Soviet tank in production. Perhaps it is possible to learn many details about the tank from the photograph, and even count the rivets in the armor—high quality data, indeed. But, unknown to the satellite team, a US military special operations unit has actually stolen one of these tanks and is keeping it in a secure location. Thus, everything that can possibly be known about this tank is already known. So this very high-quality satellite photograph (the data) is worthless from an intelligence point of view.

The inverse might also be true. Suppose a high-resolution satellite photograph taken during a huge dust storm shows a very hazy outline that cannot be identified easily. Yet, an intelligence analyst who is working on a separate problem altogether sees the photograph and is inspired even by the low quality image to re-check some other data that ends up solving a long-standing intelligence problem. In this hypothetical example, low-quality data turns out to have extremely high intelligence value.

The separating of data quality from intelligence value is a general problem, which also applies to traditional human spies as well as to ESP sources of data. This is best illustrated by the CIA’s own analysis of Star Gate.

In 1995, as part of an activity directed by Congress, the CIA was tasked to conduct a twenty-year retrospective review of the Star Gate program and report their findings back to Congress. In a release of many of the Star Gate documents in 2000, the CIA published a report entitled, “Summary Report: Star Gate Operational Tasking and Evaluation” in which they conducted a detailed analysis of forty ESP operations. Quoting from this report:

From 1986 to the first quarter of FY 1995, the DoD paranormal psychology program received more than 200 tasks from operational military organizations requesting to attain information unavailable from other sources. The operational tasking comprised “targets” identified with as little specificity as possible to avoid “telegraphing” the desired response.

In 1994, the DIA Star Gate program office created a methodology for obtaining numerical evaluations from the operational tasking organizations of the accuracy and value of the products provided by the Star Gate program. By May 1, 1995, the three remote viewers assigned to the program office had responded, i.e. provided RV product, to 40 tasks from five operational organizations. Normally, RV product was provided by at least two viewers for each task.

Data from these 40 operational tasks were evaluated by the tasking organization (not by the ESP team members) along two separate dimensions. About 70 percent of the 100 separate evaluations of these data were deemed to be possibly true or better. However, only 50 percent were deemed to be of some value, however minimal

.

Before we jump to conclusions that the spying unit was worthless, there are a number of major problems not mentioned in this particular CIA report that we must consider. First, the evaluations shown above were all gathered “after the fact.” That is, they were gathered when some form of “ground truth” was eventually determined. In all the years of research effort under the Star Gate program, they were never able to identify in advance a reliable indicator of the value of the data in a particular response, in total or in part. Thus, it would be considered a major risk to assign scarce resources to intelligence gathered by ESP without having confirmatory data from other independent sources and methods.

The conclusion was that ESP was not particularly useful, so the CIA eventually decided not to assume responsibility for the Star Gate program in 1995, although they did suggest that the academic community continue to look into ESP. Thus, the Government sponsorship of ESP activity came to a close. More on the closure, additional politics behind it, and the various reports analyzing/evaluating the project will be discussed in Chapter 10.

It was clearly a mistake to curtail the operations, based on their analysis. By the CIA’s own admission, they only evaluated forty sessions out of many hundreds, and only looked at data from 1994 onward. Even though they were requested to do so, they did not interview Joseph W. McMoneagle or any of the individuals who were responsible for McMoneagle receiving a Legion of Merit award—the highest honor for any intelligence officer—for his excellent contribution to intelligence collection.

This “inconvenient” citation was never considered in the CIA decision, nor was it part of the overall investigation ordered by the US Congress to evaluate a twenty-year-long program. So, the issue of whether the unit was pulling its own weight in the intelligence community remains murky.

According to McMoneagle’s assessment, during his time at Ft. Meade from 1978 to when he retired from the Army in 1984, approximately 15-20 percent of the cases of psychic espionage were resolved successfully. This sounds terrible—but one must remember that the program, first at SRI and later at Ft. Meade always seemed to be a court of last resort. Only the “impossible” problems were tasked: those problems that did not yield to traditional methods of intelligence collection. From that perspective, a 15-20 percent success rate is as close as one could get to a miracle. Many of those successes remain classified, along with the few that had been gained since. McMoneagle did continue with his remote viewing and his participation in Star Gate, though after his retirement from the Army he did so by being hired back into the program as a civilian contractor, working with May and his group at SRI and SAIC

.

W

ith permission from DIA, Ed May was able to interview a retired employee by the name of Angela D. Ford, who was part of the Star Gate Unit at Ft. Meade after McMoneagle had retired. From the interview, and with additional information, we’re able to describe one of her many intelligence collection successes that has also appeared on US television. One can pretty much say that with this book, as the spy novels are fond of saying, Angela has “come in from the cold.”

During a portion of her thirty years of government service, Angela Ford served as a very successful psychic for DIA. She had been trained in two types of remote viewing, called coordinate and extended, and Ford’s managers told her that she did wonderful work using both techniques. In a coordinate remote viewing session, the psychic is tasked only with locating the geographical coordinates of the intended site and uses a predefined and quite structured response method. In an extended viewing session, the psychic relaxes and free-associates, similar to the approach in the early days of SRI. In addition, we are also able to attribute to her psychic ability an amazing solution to a law enforcement case within the US Customs Department.

The case involved a Drug Enforcement Agency agent, Charles Jordan, who had turned criminal and was cooperating with drug smugglers. When the Customs agents moved in to make an arrest, he fled, which resulted in a nationwide manhunt that had failed to locate him. Most of the FBI and Customs agents involved in the manhunt assumed that Jordan would be near one of the coasts, because of his love of the sea. This turned out to be one of those examples of “when all else fails, ask a psychic.”

In the following description, we include many details of this specific case to give a better idea how an operational remote viewing is conducted, used, and its political ramifications. The names of Ft. Meade personnel have been changed to protect their identities. Here’s what Angela Ford revealed in her interview:

I didn’t know what we were doing. David (the session monitor), Carolyn (a colleague), and I went over and we worked. I wasn’t even sitting down when David said, ‘where is Charles Jordan?’ So I sat down for one second or anyway less than one minute, for sure. I looked at David and said, Lowell, Wyoming.

Okay, so David said he never heard of a Lowell, Wyoming but he had heard of Lowell, Massachusetts, because that is where he was born.

This is a good example of a violation of a well-known protocol—NEVER allow a session monitor put his or her impressions into the record. Ford continues:

I said NO, it’s Wyoming. I just kept saying that over and over again. Carolyn started to jump up and down stamping on the floor, saying, ‘She said Wyoming—she didn’t say Massachusetts!’ David grabbed an atlas and started looking at Wyoming. There is a Lovell there, and I said, close enough. Everyone thought I was crazy for saying such a

thing. Even the people at the Customs Department assigned to this case thought that there was no way this could be correct.

Later, David pulled me back into the session, and I said something to the effect of ‘I’m not sure, but you better act now because he is going to be moving,’ and I described a tomb, an Indian burial ground … go get him now … I was describing the Indian burial ground; he was going to be moving; and you have to go get him now.

David kept telling DIA authorities ‘you’ve got an isolated area up there, surely couldn’t Customs or FBI agents just go up and act on it?‘ Well, they wouldn’t. Years later I learned that apparently Charlie Jordan sent a picture of himself to his mother to let her know that he was doing well. When she received the picture, she must have called the Customs Department or FBI, but when they looked at the picture they saw a car with Wyoming license plates.

As it turned out, the DIA authorities were told that Charles Jordan was being apprehended 100 miles west of Lovell, Wyoming.”

William Green, a Customs Department official, commented on Angela’s data on television in 1995 as part of a lead-in for an ABC Nightline episode:

The collective wisdom at the time, including from everybody I talked to, was that he was probably in the Caribbean.

Jordan was finally caught in Wyoming near a National Park, near the Grand Tetons, near Yellowstone, next to an Indian reservation, next to an Indian grave site. It was almost … I hate to use the word spooky, but here is the guy next to a famous grave site, next to a reservation. It couldn’t be much more accurate than that.

Shortly after Jordan was apprehended, Mr. Green called Ed May at SAIC and told him about the case, and partly in jest asked for a job. He said that the work was most fascinating, indeed!

Even with successes like this one, the internal problems of inappropriate monitor comments in the session, the overall poor management of the Ft. Meade Unit and the lax and mostly inappropriate protocols, has led May to conclude that the US Government’s and military’s foray into the psychic business was a failure.

One problem was infrastructural. Being assigned as a commander for this special unit at Ft. Meade was a career-ender for many officers. An exception to this rule was Scotty Watt, who was the first to be assigned the role of commander because he had been passed over twice for promotion to Lieutenant Colonel. That would normally mean he was looking at retirement, because he would never reach that rank. But, as a result of his work with the original six viewers, he was promoted on his third try, which almost never happens. He made Lieutenant Colonel while assigned to the unit, the sole exception with regard to unit managers

.

Assignment of uninterested or incompetent commanders of the Unit generally led to bad protocols. More importantly, this led to a downward spiral of Unit morale, which was so poor that every time May visited the Unit at Ft. Meade, military and civilian members would take him out to lunch to complain about their boss, begging him to intervene back at DIA headquarters. “I did just that,” said May, “and while in the office of the DIA person responsible for the Ft. Meade Unit, I was offered deep appreciation for my inside information and a promise to fix things. However, no improvements were ever made. I can make an educated guess regarding why this might be the case. It has to do with how funding is handled.”

During the transition time between the closing of the SRI project and the startup at SAIC, a strange thing happened. One way in which the US Government funds things is through what is called ‘supplemental appropriations’. Normally government agencies are asked two years in advance to submit their budget request. Of course, responsible budgeting cannot do this perfectly, so the supplemental approach was designed to cover unforeseen requirements.

Government funding always runs through two or three steps. First, the funds must be authorized. Then they are appropriated, after which a joint conference between the House and Senate determines the final level of funding. Over the years, this was the way the remote viewing program was funded.

Once money is appropriated, it cannot be transferred to any entity other than some Government agency. That agency, in turn, may decide to contract the work to the private sector. Thus in 1990, a $2 million appropriation made it through Congress that was earmarked to support the Ft. Meade Unit conducting ESP research. There were two major problems. No agency had been defined to receive the funds, nor did any contractor exist. At the time, Ed May was between jobs at SRI and SAIC.

The obvious place for Congress to target that funding was the Defense Intelligence Agency, but its commander at the time, Lt. General Harry E. Soyster, refused to accept the money for a program he had no appreciation for in the first place. So here is the crux of the problem. As May remarks, “I saw a letter from the Senate Select Committee for Intelligence, the Congressional committee that put in an authorization request for the funding, giving General Soyster twenty-four hours to show why he was not in contempt of Congress for not accepting this $2 million appropriation.”

This kind of macho ‘I’m-bigger-than-you-are’ approach may appeal to the fighter in us all, but it is a disaster as a management approach. It forced a controversial program down the throat of an uncooperative Defense Department agency. As you can imagine, this angered the military management at DIA. “So, yes, we got the funding, but at every turn DIA successfully created conditions that would make the Unit ineffective—for example, assigning generally incompetent dead-

enders as Unit commanders. However, this is just my guess as regards one of our core problems.”

There was also the notion that the problem lay with Ingo Swann’s training idea (not with Ingo personally), and may be easier to defend. May blames the SRI project management team for not putting the required scientific discipline into operation, to determine the degree to which Ingo’s idea was or was not sound. This had the effect of injecting two inappropriate attitudes into the Ft. Meade Unit, the negative results of which last through today. During this time, May was not part of the project management but a senior research physicist assigned to the project.

The concept behind Ingo’s remote viewing training idea was based upon one very sound scientific principle and, in addition, an often-heard anecdotal concept. Many people are aware of B. F. Skinner and his behavioral ideas in psychology. As an example, a pigeon can be trained to press a lever to get food by rewarding it with food pellets every time it may have randomly bumped into the lever. Over time, the bird recognizes what is necessary to do to get the food. An extension to this basic idea is called operant conditioning, which Wikipedia (admittedly not the best source) defines as follows:

Operant conditioning is the use of consequences to modify the occurrence and form of behavior. Operant conditioning is distinguished from classical conditioning (also called respondent conditioning, or Pavlovian conditioning) in that operant conditioning deals with the modification of ‘voluntary behavior’ or operant behavior. …

One necessary aspect of operant conditioning in biofeedback is that the reward follows rapidly after the desired behavior. Ingo latched on to this idea first by breaking the well-known and sacrosanct requirement when doing experiments that they must be conducted under double-blind conditions. In the context of an ESP trial, no one who knows anything about the ESP target may have any interaction whatsoever with the psychic. This idea is true for all laboratory studies and for the beginning of all operational uses of ESP—though depending upon the circumstances, it may be useful to begin to break this rule in operations, but for very proscribed reasons. Ingo, of course, knew this as well as did the SRI project management.

However, they made the decision to violate the double-blind requirement with a variation of the tired and false argument that “the end justifies the means.” So, in the vast majority of training sessions where Ingo took on the role of trainer, he was looking at the target photograph and the trainee was sitting across a table from him. Professor (Emeritus) Robert Rosenthal, the renowned psychologist from Harvard University, and others have amply demonstrated the power of nonverbal communication. In fact, if someone who effectively expresses ideas nonverbally is paired with someone who is equally good at understanding others who communicate

that way, then that form of communication may surpass normal verbal communications. It can certainly seem psychic.

To illustrate how this might work in an actual ESP training session, imagine you are the trainee. The trainer is sitting opposite you, and is looking at a picture of a waterfall. Let’s further assume that you possess absolutely no psychic ability at all, so you just report out loud whatever random impressions come to your mind. The trainer properly remains silent through your two-minute discourse on your guess about the target photograph. However, unconsciously, the trainer leans slightly forward when you mention water and slightly backward when you mention desert, while cliffs and trees in your discourse result in other forms of unconscious behavioral feedback. As Rosenthal’s research clearly demonstrates, you will begin to talk more about a cliff, trees, and water, and arrive quickly at the idea of a waterfall. This would appear as if you were doing remote viewing, when you actually had no such ability.

Although May emphatically pointed out the influence of unconscious nonverbal behavior in this training format, his strong objections went unheeded. As bad as breaking the double-blind rule was, “It was only the first of two fatal mistakes Ingo was allowed to commit,” said May. Misunderstanding the rules of operant conditioning, Ingo thought that he could reinforce good remote viewing by giving quick and immediate feedback, in session, when a trainee mentioned something. At first glance, this sounds perfectly reasonable—in proper training sessions, the trainer rewards real trainees as having done excellently in psychically accessing the target. But it’s the timing of the feedback that’s important.

Going the way Ingo proceeded makes it a major disaster. When Ingo gave the feedback, the trainee marked the appropriate element with a feedback symbol. To be precise, we quote from a formerly secret memorandum from an official of the special access ESP spying program2

called SUN STREAK to the then Deputy Director for Science and Technical Intelligence at the DIA. The description in the memorandum that follows is quoted verbatim from the appropriate SRI report.

(S/SK/WNINTEL)3

CLASS C: The majority of the training sessions for novice trainees are Class C. During this phase, the source trainee must learn to differentiate between emerging target-relevant perceptions and imaginative overlay. To assist the trainee in this learning, immediate feedback is provided during the session. The interviewer is provided with a feedback package which may contain a map, photographs, and/or a narrative description of the target. During Class C sessions, the interviewer provides the trainee with immediate feedback for each element of data he provides. No negative feedback is given. Should the trainee state an element of information that appears incorrect, the interviewer remains silent. Feedback, in order to prevent inadvertent cuing (interviewer overlay), is in the form of very

specific statements made by the interviewer. These statements and their definitions are as follows:

Correct (C)—The information is Correct in context with the site location, but is not sufficient to end the session.

Probably Correct (PC)—The interviewer, having limited information about the target, although he cannot be absolutely sure, believes that the information provided is correct.

Near (N)—The information provided is not an element of the specific site, but is correct for the immediately surrounding area.

Can’t Feedback (CFB)—Due to limited information about the target, the interviewer cannot make a judgment as to the correctness of the data. It means neither correct nor incorrect.

Site (S)—The site has been correctly named for the specific stage being trained (man-made structure for Stage I, bridge for Stage III, etc.). “Site” indicates that the session is complete.”

At first glance, all this seems entirely reasonable. Then as now, it seemed reasonable to Ingo as well as to a plethora of would-be remote viewing trainers on the Internet, who since have naively adopted Ingo’s methods. However, this putative training approach is utterly incorrect. Leaving aside the problems of inadvertent cuing by nonverbal communication, which is certainly bad enough, a host of fatal flaws can be found in this approach.

First, a trivial example: Ingo never wanted to provide negative feedback like “you missed,” “you’re wrong,” or “incorrect.” So as the quote above clearly states, if the trainee hears no feedback after he or she has given an element in the psychic impression, it is, by definition, wrong, and she or he clearly has received a form of negative feedback—which violated Ingo’s idea of no negative feedback in the first place.

The major flaw is likened to a popular game that was also a radio quiz show in the US in the 1940s and 1950s, Twenty Questions. In that show, a contestant was told that the hidden topic was “animal, vegetable, or mineral.” The contestant then asked up to twenty questions that could only be answered by “yes” or “no.” The challenge lay in whether or not, within those twenty questions, the contestant could find the right answer, in which case he or she was rewarded with a prize. Of course, many contestants were successful, which added to the show’s popularity, and we’re sure our readers have likely played a version of that. In fact, there is an electronic toy called 20Q and associated website (20Q.com) where you can think of something, someone, or someplace and have the device/program ask you questions. It’s an uncanny thing.

Ingo’s training feedback approach was and is a variant of the Twenty Questions game. Assuming no psychic ability whatsoever, a person could arrive at the correct

site via clever responses, conscious or unconscious. This problem was immediately clear to those who were on the SRI team, and to Dale Graff, a civilian working at DIA. Yet, it was allowed to stand.

What is so terribly wrong with this approach?

Answer: you have no idea whether or not you are training remote viewing, training sensitivity to nonverbal communication, simply playing the game of Twenty Questions, or perhaps a combination of the above. And yet the intelligence community might waste resources or even lives by acting on such ambiguous information from individuals “trained” by this flawed technique. And if the US Government was giving SRI many hundreds of thousands of dollars to develop a training methodology for the Army, one can say this borders upon noncompliance of contract at best and outright fraud at worst.

As a scientist, Ed May voiced strenuous objection to this approach—not only to the project management at the time but also to an on-site DIA representative, Jim Salyer, as well as to Ingo himself. “I was frustrated, because I thought the basics of Ingo’s idea deserved much better treatment than it was being given. Ingo was not a scientist, and because of this, the responsibility of determining the validity of his creative ideals was our responsibility and not his.”

Another area where May thinks a mistake was made with Ingo’s training idea is a sort of a one-size-fits-all mentality. “While I did not know it at the time, I have since learned from very high-ranking Army officers that part of the psychology of Army culture is this mentality of not recognizing individual differences, something well-understood in the field of psychology. The Army appears to think that any well-trained soldier who is given a stimulus will respond exactly the same way every time, and every soldier will also respond exactly the same. Of course, this is not even close to being true.”

When Ingo was developing his training method at SRI and trying it out on local people with natural psychic abilities, “we nearly had riots on our hands!” said May. “Ingo set the rules, and they applied to everyone. In fact, one such rule was ‘Content be Damned—Structure is All that Matters!’ This related to Ingo’s training procedure and the actual structure of what to do with the perceptions as they came to the viewers, such as how the folks needed to put their data down on paper (even where on the paper to put the perceptions as they happened). The rule meant that it didn’t matter as much what the viewers perceived (content) as how they recorded it (structure), which seems somewhat counter-intuitive. Ingo enforced this rule with an iron fist, and made people contribute money to a kitty each time it was violated. Some of these talented ‘guinea pigs’ quit the training in fear it would harm their natural ability.”

Although Ingo and May were good friends, somehow his criticism disturbed Ingo deeply. He was further upset as May voiced a strong opinion that, while recognizing that training Army personnel in New York City would be very

convenient for Ingo since he lived there, May felt it was terribly inappropriate for him to do so unsupervised. “In addition, I had explained to him that the training methodology was fatally flawed,” which certainly couldn’t have made the psychic happy.

Once again, May’s concerns were ignored. Ingo worked, unsupervised, in SRI’s New York office with a number of personnel from the newly established Unit at Ft. Meade. Because he was angry at egghead scientists in general and Ed May in particular, he instilled bogus thinking in his trainees which has endured to this day. This “poisoning of the well” took the form that protocols and science are perhaps good for the laboratory, but the “real-world people” who were saving the world against communism did not need to pay any attention at all to the scientists. When May became the project director in the fall of 1985, this negative attitude was palpable during his many visits to Ft. Meade.

But the proof was in the pudding. Regardless of the obvious flaws, if individuals who were trained by this method could produce actionable intelligence, then one can say May’s supposition is wrong.

Until Joe McMoneagle retired in 1984, all the intelligence success came from him or one of the other original six remote viewers. Very few, if any, of the successes came from Ingo-trained people. Since McMoneagle was the last of the original six psychics who left the Unit, the success rate plummeted and the successes were highly concentrated with people such as Angela Ford, who were never trained by Ingo. McMoneagle’s decision to retire from the Army and leave the Unit was totally predicated on the erroneous and bogus training method pushed by Ingo and his trainees. The fact was that the methodology wasn’t working in early testing within the Unit. There was the further obvious problem that there were going to be no other attempts to recruit people with natural psychic ability. This could only result in eventual failure with the Unit and Joe’s burning out completely as the only remote viewer.

There were a number of consequences that resulted from the anti-science attitude in the Ft. Meade Unit. After the Unit was established, the Army, and later the DIA, paid the personnel at SRI and later at SAIC millions of dollars to conduct research with the primary goal of improving the quality of the psychic output at Ft. Meade. The civilian project personnel did just that and, from an academic perspective, gained significant progress towards the understanding of ESP. But, there was an uneasy relationship between Ft. Meade and SRI/SAIC, As a result of the anti-science bias, the DIA eschewed much of the data from SRI/SAIC, which helped lead to the eventual closure of the program.

Beginning in 1986, the Air Force was exceptionally interested in learning the degree to which remote viewing could provide useful information on directed-energy weapon systems. To test this idea, they awarded May and company a contract to examine this question in three trials—one per year, for three years

.

As always, they used a double-blind protocol, meaning that no one who interacted with the psychics knew anything about the potential target, or even in this case, the identity of the client.

As discussed in Chapter 3, a session would involve the Social Security number of an individual none of them had met, that on a specific date this person would be somewhere in the continental United States, and May having knowledge that the targets would be directed-energy systems of some kind, but no specifics beyond that. The analysis of the result was a breakthrough, with implications beyond laboratory studies.

For the results and the analysis, the way to obtain a high figure of merit—again, the product of accuracy and reliability of the information—was for the psychic to describe as much of the intended target as possible, but in as simple and minimal a way as possible and not to include many incorrect aspects. To get a hint of what a random response could be like in the absence of any psychic ability, they had determined in the laboratory that using a rough rule of thumb, about a third of any site can be described by about a third of any response—sort of like the 100th

monkey on a typewriter analogy.

One of the best examples was discussed in Chapter 3, the target being Project Rose, a high-frequency, high-power microwave device in the New Mexico desert at Sandia National Laboratory.

The point in all this detail bears repeating: their system of analysis had the potential to allow an operations analyst looking at real psychic spying data to evaluate the results quantitatively. Combining that analysis with more traditional methods of intelligence collection, the military could more accurately assess whether or not it made sense to invest further resources.

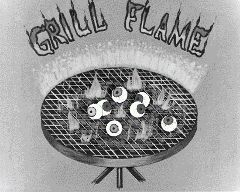

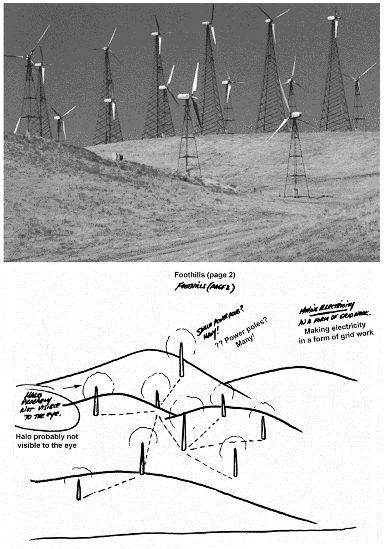

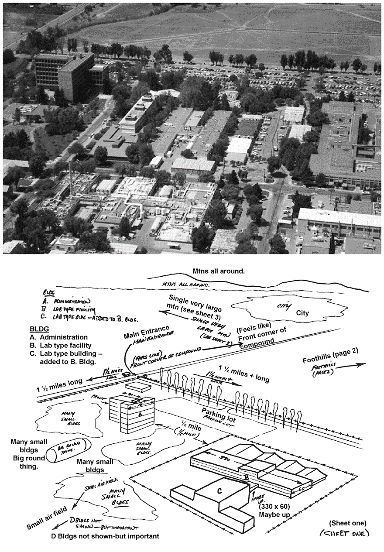

Another excellent example involved three targets at or around Lawrence Livermore Laboratory (now Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory—LLNL) in Livermore, CA, about 50 miles east of San Francisco. The primary target system was the Advanced Technology Accelerator located approximately 10 miles from the lab. A secondary target was the windmill farm at the Altamont pass through the hills east of Livermore, and a tertiary target was the West gate of LLNL.

The following are examples of visual correspondences in the remote viewing. The accelerator response is shown as a partial drawing, but the remaining responses are the complete drawings for the targets.

The partial response to the electron accelerator shown below describes a beam being labeled as three feet in diameter whereas the actual electron beam is about 0.3 mm. But for McMoneagle to even recognize there is a beam involved is not only a testimony for his skill but for ESP in general. The other targets are near-perfect in depiction by what was drawn in the remote viewing.

The electron accelerator and a partial response (annotated for clarity)

The secondary target windmill farm and the complete RV response

The tertiary target of the West Gate of Lawrence Livermore Laboratory and the complete RV response

As mentioned previously, the experimental team had no information as to what the specific target or its location might be. As can be plainly seen by the above images, the visual correspondences were stunning

.

May’s group had numerous examples of laboratory-verified studies that, if used, would have increased the effectiveness of the Ft. Meade psychic spying unit. But sadly, the group was considered to be composed of “just those scientific eggheads in California,” said May. “What did we know about the real world of intelligence collection? It seems an abhorrence of science, and the unscientific attitude won out.”

Shortly after the government closed the Ft. Meade Unit, Congress required them to send all their records to the CIA. They sent approximately thirty-five sealed boxes so that the Agency could conduct their Congressionally directed evaluation of the Star Gate program. In both the classified and unclassified versions of their report to Congress, they implied that the result of their careful examination of the record showed that further military or intelligence community support was not warranted.

Two years later, after the CIA program evaluation reports had been published, two colleagues, one from DIA and one from the Pentagon, officially had access to the room at the CIA in which all the boxes were stored. What they found was a bit disturbing: Not a single one of the boxes had ever been opened! So much for a careful and in-depth review of the material as required by the US Congress. This is one terrible consequence of self-defeatism and of a well that was poisoned against scientific inquiry.

Since the DIA person had helped pack the boxes, and could identify which ones to open, in a matter of minutes they were able to find incontrovertible proof of intelligence collection examples that were not only successful, but constituted a valuable contribution to solving the problem at hand. Thus, one must question the veracity—or ignorance—of former CIA Director Robert Gates when, on the news television program Nightline in 1995, he said:

Well, I can say is that in the 20 years or 25 years where I was in a position perhaps to be aware, I don’t know of a single instance where it is documented where this kind of activity contributed in any significant way to a policy decision or even informing policymakers about important information.

This statement is either blatantly false, or a result of ignorance or a conveniently faulty memory not worthy of a former Director of the CIA. “Director Gates knew that I knew he had been briefed on specific examples to the contrary,” said May. “In fact, my role on this episode of Nightline was simply to act as a foil to Director Gates. Many of my comments contradicting him were edited out in the final aired version. I chose to go on this program, even though my managers at SAIC ordered me not to, and I was threatened, by implication, that both CIA and SAIC lawyers were going to watch the show for any transgressions I might commit. My only alternative was to resign my post at SAIC effective immediately.” The full story of this and more on the Nightline appearance and its fallout is discussed in Chapter 10.

May went on to say, “I am saddened that the picture I have painted had to reveal such bias, ignorance, and mismanagement of what could have been a valuable asset

in the arsenal of intelligence collection tools. I suppose my main disappointment, however, lies in the consequences that continue today.”

One relatively small consequence is the explosion of ethically challenged remote viewing courses being hawked on the internet by former low-level, scientifically untrained military and civilian personnel from the Ft. Meade Unit, which cost unsuspecting clients substantial amounts of money. These courses promise that their operant conditioning-derived training methods will turn their customers into expert remote viewers. But their training suffers from the “fatal flaws” we described above. In addition, said May, “Joe McMoneagle, and to a lesser extent I myself, have received painful phone calls from former customers of these near-fraudulent training courses complaining that they could not perform remote viewing at all when they tried to conduct sessions on their own at home in front of their families and friends.”

A much more important consequence, however, is the fact that the US Government is apparently not using psychic intelligence as an additional aid in the required intelligence collection in our time of terrorism. Three reasons come to mind regarding why this is the case.

The first and probably the most important one is that the diehard “believers” in the Ft. Meade Unit set up expectations for the veracity of psychic-derived intelligence that not only weren’t credible but, in fact, could never be met. This attitude can be traced directly back to Swann and his unsupervised indoctrination of Army and DIA personnel. The fault for this lies directly with the SRI management of the program. Failed expectations based on irrationally high expectations and unattainable results are a sure way of killing any project. Unfortunately, they killed this one.

Another contributor to the lack of use of psychics today is the fact that from 1972 to 1995, we had benefited from a limited number of very brave and dedicated US Government officials, including Senators, Congresspersons, Congressional staffers, and agency directors and deputy directors. These persons, in many cases, put their jobs and reputations on the line to protect the project’s very fragile activity. Now, many of them have retired.

Finally, counterterrorism is both a tactical as well as a strategic problem. Although psi is significantly better when applied to strategic problems, nonetheless the proper use of psi can assist in planning for military operations in the future. The shift of terrorism to unconventional and transcendent warfare opens the door to psychic collection methodologies being used even more effectively.

Joe McMoneagle and Ed May, even with total cooperation by the top management as well as that of General Alexei Savin of the on-going Russian remote viewing program, were unable to convince a number of elements within our intelligence community of the worthiness of even a baby step in this direction. With Savin’s blessing, May created a detailed intelligence contact report after a visit to Russia in 2000. Later he was able to hand this stunning report to the DIA director,

Admiral Thomas R. Wilson. It described in detail the major management players of the Russian psychic program by name and by their positions in the reporting chain within the Russian military, and it included information about some of the psychics and their abilities and achievements. Lastly, May was able to emphasize to Admiral Wilson that General Savin wanted to create a joint American/Russian program to use psychics to deal with the common challenge of counterterrorism.

Nothing ever came of it. How tragic.

There’s more to this part of the story, of the final days of Star Gate, why it was not picked up by another agency, and how the results were buried amidst incorrect assessments of the project’s results. We’ll get to all of that after we take a slight detour in space and time to consider what our Soviet/Russian counterparts were doing all this time.

Notes:

1. Grill Flame was the second cover name for the group at Meade. The first one was Gondola Wish. These cover names were especially handy in that they could be used in an unclassified environment, like the telephone without the worry of compromising the secret nature of the work.

2. A special access program, or SAP for short, is a highly classified project that only specified individuals who had been read-on and signed legal documents could have access to the material regardless of the clearance level they may have possessed.

3. This is called portion marking wherein each paragraph in a classified document must indicate the level of classification for that paragraph. Here, the S means secret; the SK means SUN STREAK, and the WNINTEL means Warning Notice—Intelligence Sources & Methods Involved.